Introduction

Angina is a clinical syndrome with symptoms attributable to myocardial ischaemia, most commonly related to underlying occlusive coronary artery disease.

Angina is a clinical syndrome with symptoms attributable to myocardial ischaemia, most commonly related to underlying occlusive coronary artery disease.

Long-term prognosis for those with stable angina is variable, with mortality rates of between 0.9%– 6.5% per annum. An individual’s risk is determined by their baseline clinical, functional and anatomical characteristics, illustrating the importance of careful risk stratification to ensure optimal treatment (whether medical, interventional or a combination of both) and outcomes.

The range of treatment options in angina, and their evidence base, has evolved considerably over the last few years, with the objective of ideally not only controlling symptoms but also improving prognosis. Guideline-compliant therapy is associated with improved outcomes, including reduced rates of cardiovascular events and death.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recently commissioned the National Clinical Guidelines Centre (NCGC) to develop a clinical guideline on the management of stable angina.1 In particular, the recommendations focus on the relative merits of medical therapy and revascularisation, and the role each strategy has in improving quality of life, morbidity and mortality. This article reviews the key recommendations and the implications for clinical practice, with particular emphasis on primary care.

Treatment

The aims of treatment in stable angina are two-fold, to minimise symptoms and improve quality of life, whilst also ensuring the timely institution of medical therapy or revascularisation to improve prognosis by preventing myocardial infarction or death. Both of these approaches should be supported by positive lifestyle measures, including encouraging activity within the patient’s limitations, supporting smoking cessation and adopting a Mediterranean diet. There is no evidence that vitamin or fish oil supplements confer benefit in stable angina.

Optimal control and management of co-morbidities, including hypertension, diabetes and renal disease, is important in modifying the atherosclerotic disease process and improving outcomes in those with stable angina.

Pharmacological therapy to improve prognosis

The guidelines support and endorse the implementation of secondary prevention therapy in patients with stable angina, to reduce the progression of cardiovascular disease and improve prognosis. The recommendations are:

- Aspirin 75 mg daily, taking into account the risk of bleeding and co-morbidities. Treatment is associated with a statistically significant reduction in non-fatal myocardial infarction and vascular events although, due to the heterogeneity of those with stable angina, there is a relatively low-risk cohort in whom the bleeding risk may outweigh any potential gain.

- Statin treatment should be offered to all those with stable angina, in line with current lipid modification guidelines and targets.

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors should be considered for those with stable angina and diabetes. The evidence reviewed suggested potential benefit in this group of patients, although it is recognised there are other compelling indications for ACE inhibitors, in particular in those post-myocardial infarction, those with left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction, reno-vascular disease and hypertension.

Treatment of symptoms

Minimising, or ideally eradicating, symptoms in stable angina is a key objective and, for the majority of patients, results in an improvement in their quality of life and exercise tolerance, as well as having a significant bearing on the need for further investigation or revascularisation.

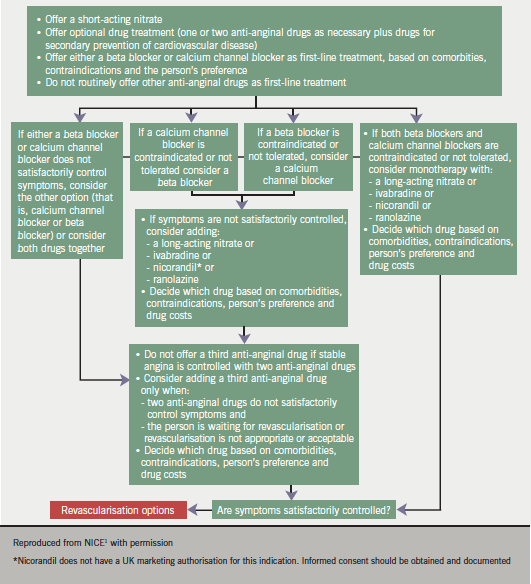

The guidelines provide a useful treatment algorithm with optimal medical treatment being defined as the use of up to two anti-anginal drugs plus secondary prevention measures (figure 1).

Consideration to adding a third anti-anginal drug should only be given when:

- the person’s symptoms are not controlled with two anti-anginal drugs and

- the person is either waiting for revascularisation or revascularisation is not considered appropriate or acceptable.

Symptoms of angina can effectively be relieved by the use of short-acting nitrates, including glyceryl trinitrate as a sublingual tablet or spray. The individual should be carefully instructed in its use and also of the potential benefit of using it before any planned exercise or activity (‘situational prophylaxis’). Short-acting nitrates should be prescribed for all those with stable angina.

First-line treatment

The guidelines recommend, as first-line treatment, either beta blockers or calcium channel blockers. These are effective in reducing anginal symptoms by reducing myocardial oxygen consumption, as a result of lowering heart rate, myocardial contractility and blood pressure, coupled with increasing coronary blood flow and myocardial oxygen supply during diastole.

The decision as to which therapy to chose, either a beta blocker or a calcium channel blocker, should be based on the individual’s co-morbidities, contraindications and preference. If they are unable to tolerate either of these therapies, then consideration should be given to switching to the other. The recommendation is not to routinely offer anti-anginal drugs other than a beta blocker or calcium channel blocker as first-line treatment in stable angina.

If symptoms are not satisfactorily controlled on either option alone then the recommendation is to consider using a combination of a beta blocker and a calcium channel blocker, although the latter should be a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (amlodipine, slow-release nifedipine or felodipine).

Second-line treatment

For those individuals in whom symptoms persist, despite optimisation of their beta blocker or calcium channel blocker dose, consideration should be given to introducing additional anti-anginal therapy. These may also be considered as initial monotherapy when the patient is intolerant of either a beta blocker or calcium channel blocker. These therapeutic options include:

- long-acting nitrates

- ivabradine

- nicorandil

- ranolazine.

The decision on which drug to use should be based on co-morbidities, contraindications and patient preference.

Long-acting nitrates reduce the severity and frequency of angina attacks, and may increase exercise tolerance, although they have not been demonstrated to confer any prognostic benefit.

Ivabradine acts by inhibition of the sinus node, reducing heart rate and myocardial oxygen demand during rest and exercise, with evidence of proven anti-anginal efficacy, and can be prescribed in combination with either a beta blocker or dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker.

Nicorandil has a dual mechanism of action, as a potassium channel activator and also with a nitrate moiety that dilates epicardial coronary arteries, with a nitrate-like effect. Trial data have demonstrated a reduction in hospital admissions for cardiac chest pain in patients with stable angina.

Ranolazine is a metabolically acting agent, which is believed to selectively inhibit sodium channels, with minimal reductions in heart rate and blood pressure.

When counselling patients with regards to the relative merits of medical treatment, it is helpful to advise them that the aim of anti-anginal treatment is to prevent episodes of angina, and the aim of secondary prevention to prevent cardiovascular events, including myocardial infarction and stroke.

All anti-anginal therapies should be titrated, depending on the patient’s symptoms, to their optimal tolerated doses (within the licensed dose range) before considering adding additional therapy.

Medical therapy versus revascularisation

The two conventional approaches to revascularisation in patients with coronary artery disease are percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG). The latter procedure has been developed and refined, including more recent off-pump (avoiding the need for circulatory bypass) surgery over the last 40 years, while results with PCI started have improved significantly following the introduction of coronary artery stents 15 years ago.

Despite extensive trial data and research, there is still persisting uncertainty regarding the indications for, and optimal timing of, invasive investigation and revascularisation in stable angina, although there is clear evidence that an early investigation and intervention strategy significantly improves outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome and in those with high-risk coronary anatomy.

Patients who remain symptomatic despite optimal medical therapy should be considered for revascularisation and, in order to decide which procedure may be appropriate, invasive investigation (angiography) should be offered. A proportion of these patients may still require functional testing to evaluate angiographic findings and guide treatment decisions.

A proportion of patients whose symptoms appear to be controlled with medical therapy may still potentially have coronary lesions, which are prognostically significant, including left main stem or proximal three-vessel disease. These patients would benefit from a revascularisation strategy and the guidelines recommend considering a non-invasive functional (stress echo or myocardial perfusion scan) assessment to help risk-stratify these patients. In those patients in whom there is evidence of extensive ischaemia, angiography should be offered.

In patients with angina, both PCI and CABG have proven efficacy in improving symptoms although, on available evidence, PCI does not appear to provide substantial survival benefit. CABG has been shown to improve prognosis in a subset of patients including those who:

- have anatomically complex three-vessel disease, with or without involvement of the left main stem

- have diabetes mellitus

- are aged over 65.

If the patient’s coronary anatomy is considered suitable for either procedure, then it is recommended that PCI should be offered in preference.

Fuctional assessment and risk stratification

Within the population with stable angina there is significant variance in respect of a particular individual’s prognosis, with an up to ten-fold difference in annual mortality between those deemed to have low risk and those with high risk. This emphasises the importance of early risk stratification to identify those patients who will benefit prognostically from a more intensive treatment or interventional approach.

The four most important pieces of information required to assess an individual’s risk, and hence prognosis, accurately are:

- clinical evaluation (history, examination, ECG, lifestyle factors, smoking, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, hypertension and lipids)

- response to stress testing

- quantification of LV function (impaired LV systolic function is the strongest predictor of poor prognosis; resting left ventricular ejection fraction < 35% is associated with an annual mortality of > 3% per year)

- extent of coronary artery disease.

Non-invasive functional assessment, including stress echo, myocardial perfusion imaging or exercise ECG, is useful in identifying those individuals who may have high-risk coronary anatomy and are likely to benefit from revascularisation. The role of the exercise ECG in current practice appears increasingly to be limited to assessing functional capacity in those with established coronary disease, rather than in the diagnostic pathway, due to the test’s relatively poor specificity and sensitivity as compared with other functional imaging tests.

Rehabilitation

There is good evidence that cardiac rehabilitation programmes are beneficial to individuals with cardiovascular disease, in particular post-myocardial infarction or coronary revascularisation. In stable angina the evidence is less robust and the guidelines recommend a more tailored approach to rehabilitation, depending on the individual’s particular needs, including psychological support if required.

The Angina Plan2 provides a structured programme of support for both individuals with angina and their carers, which appears to be particularly beneficial.

Summary

The increasing prevalence of angina, due to an ageing population and improved survival of those with conditions which predispose to the development of coronary atherosclerosis, including diabetes, hypertension and renal disease, provides us with challenges in ensuring patients receive timely investigation and optimal treatment, including potential intervention. Fortunately, we have a wide range of effective management options at our disposal which have the potential to significantly improve our patients’ symptoms, and hence quality of life, as well as their prognosis.

It is important we employ these strategies effectively to ensure our patients achieve the greatest benefit from their given treatment or intervention, as well as taking time to accurately risk-stratify individuals to identify those at higher risk who would benefit from more intensive investigation and treatment, including revascularisation.

The guidelines are helpful in detailing the evidence base supporting the current recommendations and these will no doubt have a significant positive impact on the management, quality of life and prognosis of our stable angina patients.

References

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. NICE clinical guideline 126. Management of stable angina. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2011. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG126

- The Angina Plan. www.anginaplan.org.uk