The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on chest pain recommended the use of computed tomography coronary angiography (CTCA) in patients with low pre-test probability, functional tests in patients with moderate pre-test probability, and invasive coronary angiography (ICA) in patients with high pre-test probability, of having coronary artery disease (CAD). A previous audit demonstrated low incidence of CAD in patients with moderate and high pre-test probabilities. We investigated these patients non-invasively and assessed outcome.

We retrospectively reviewed 213 consecutive patients who were seen in the outpatient setting and had a moderate or high risk of CAD based on NICE CAD score. We compared the performance of the tests.

CTCA was performed in 107, stress echo in 67 and myocardial perfusion scintigraphy (MPS) in 39 patients. The MPS group were older (p<0.01) and had a higher incidence of risk factors (p<0.01). Of the patients undergoing CTCA, 9.4% were found to have significant CAD requiring revascularisation. Functional testing led to revascularisations in 4.7%. The higher rate of revascularisation in the CTCA cohort was not statistically significant (p=0.28).

Our real-world data suggest that CTCA can be at least as effective as functional tests in detecting significant CAD and may lead to more revascularisations than functional tests. CTCA should be considered as an effective alternative to functional tests in patients with higher pre-test probability of CAD in hospitals with limited access to functional tests.

Introduction

In 2010, the UK National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published guidelines on the investigation of patients with chest pain and recommended the use of cardiac computed tomography (CT) in patients with low pre-test likelihood of having coronary artery disease (CAD).1 They also recommended that patients with moderate pre-test likelihood should have an imaging functional test such as myocardial perfusion scintigraphy (MPS) or dobutamine stress echo (DSE), and that patients with a high pre-test likelihood should be investigated with invasive coronary angiography (ICA) as the first-line investigation. NICE recommended the use of a risk score (CAD score) to assess pre-test probability. The CAD score was adapted from the Duke clinical score.2

Before implementing the NICE guidelines in our hospital, we audited the incidence of CAD in patients attending rapid access chest pain (RACP) clinics and found that the majority of patients with a high pre-test probability (CAD score >60%) who underwent ICA had normal coronary arteries. The incidence of confirmed CAD in patients with CAD score of 30–60% was 8.7% and in patients with CAD score >60% was 23.2%.3 This may either reflect a lower incidence of CAD in our population, or that the CAD score overestimates the prevalence of CAD in primary care populations, which is acknowledged in the NICE guidelines.1 Hence, we elected to investigate patients with both moderate and high pre-test likelihood with imaging functional tests.

NICE recommend the use of imaging functional tests in place of exercise tolerance tests (ETT) because of their superior sensitivity and specificity.1 The drawbacks of functional tests are their cost, and DSE can be labour-intensive. Furthermore, the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) appropriateness criteria for CT coronary angiography (CTCA) recommend its use in patients with low-to-moderate likelihood of having CAD.4 This is based on numerous studies, including three recent clinical trials that demonstrated CTCA to have an excellent negative predictive value (NPV) and very good sensitivity for the detection of CAD.5-7 Hence, we elected to extend the use of CTCA to patients with CAD score 30–90%. The availability, speed and reliability of CTCA in our hospital encouraged clinicians to refer such patients for CTCA.

We conducted a retrospective study to look at the clinical effectiveness and six-month outcome of the use of CTCA in patients with chest pain, who presented to the RACP or general cardiology clinics. We calculated the CAD score for all patients and, for the purposes of this study, excluded patients with low (10–29%) CAD scores. We compared the performance of CTCA with that of imaging functional tests (DSE and MPS) in patients with moderate (30–60%) and high (60–90%) CAD scores.

Methods

Patients

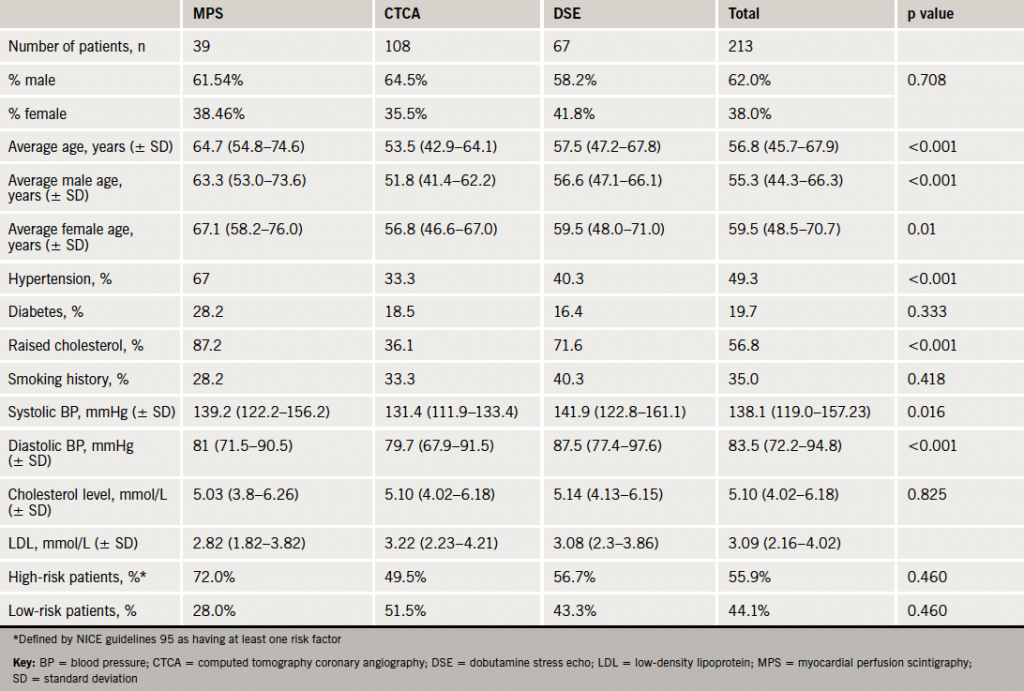

We analysed data from August 2010 to April 2012 for patients who underwent CTCA for the investigation of chest pain after attending RACP or general cardiology clinics. There were 107 patients with moderate and high CAD scores. We also looked at 106 consecutive patients from April 2012 backwards who had undergone functional testing (DSE or MPS) and who attended these clinics. Inclusion criteria required patients to be in the moderate-to-high CAD score categories, as calculated by NICE guidelines 95. The choice of functional test in our hospital is down to the cardiologist’s preference. Baseline demographic data were obtained retrospectively from clinical notes and electronic radiology and biochemistry results. Follow-up data were obtained from clinic letters. Hospital records were checked at six months for re-admissions and deaths. Baseline patient characteristics are summarised in table 1.

CTCA

Patients were beta-blocked by the referring clinician (atenolol 50 mg) and/or intravenously with metoprolol (5–30 mg) aiming to achieve a heart rate of <60 bpm. All patients received two 400 µg doses of sublingual glycerol trinitrate. All CTCA were performed with a 64-slice LightSpeed VCT XTe GE scanner (GE Healthcare) and prospective gating using the commercially available protocol (SnapShot Pulse, GE Healthcare) and the following scanning parameters: slice acquisition 64 × 0.625 mm, scan field of view (SFOV) cardiac, Z-axis detector coverage 40 mm, gantry rotation time of 350 ms. Patient’s size was visually judged for adapted tube voltage; 100 kV was used for small patients, 120 kV for average size patients. Similarly, effective tube-current ranged between 500 mA and 650 mA based on patient’s size judged visually. We only acquire the 75% phase or the RR-cycle. CTCA images were reconstructed with slice thickness of 0.625 mm, on an external workstation (ADW 4.5, GE Healthcare). Significant CAD on CTCA was defined as >50% diameter stenosis. The decision on further investigation was down to the cardiologist’s judgment. ICA +/- proceed was chosen for the more proximal and severe stenosis.

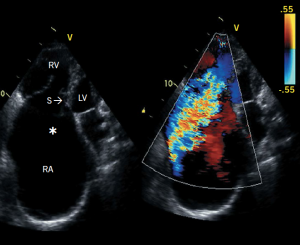

DSE

All patients were scanned using a Philips IE33 echocardiography machine. The images were acquired by a trained cardiac physiologist with a consultant cardiologist reporting the scans. Intravenous dobutamine was administered via a syringe pump starting with 10 µg/kg/min and increased up to 40 µg/kg/min. Boluses of atropine up to a maximum of 1 mg were added if the target heart rate of 85% of maximum predicted was not achieved. Images were captured at rest, low-dose, pre-peak and peak heart rates. Sonovue contrast was used at the discretion of the cardiologist if the image quality was suboptimal.

MPS

Studies were performed under standard departmental protocols with a conventional gamma camera with sodium iodide detector and single photo emission computed tomography (SPECT) with technetium radiotracer. Images were acquired at rest and at stress, which was induced with adenosine intravenously at a rate of 140 µg/kg/min for six minutes with injection of radiotracer four minutes after the start of the infusion. All images were reviewed by a radiologist and a cardiologist.

ICA

Patients underwent ICA at King’s College Hospital, and were all reviewed by a consultant interventional cardiologist. Severe CAD on ICA was defined as ≥70% diameter stenosis of at least one major epicardial artery. Functional analysis with fractional flow reserve (FFR) was used at the discretion of the interventional cardiologist before revascularisation.

Statistical analysis

A chi-squared test was used to compare the proportions of male/female patients, the presence of risk factors between the CTCA, DSE and MPS groups and the rate of revascularisations. For comparing the risk factors between the MPS, CTCA and DSE groups and the total sample an ANOVA test was used. A p value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

The average age of the subjects was higher in the MPS group (64.7 years), when compared with the CTCA group (53.5 years, p<0.001) and the DSE group (57.5 years, p=0.002). In total there were 132 males and 81 females, but there was no significant difference between the sexes in any of the groups (p=0.71). There was no significant difference in the incidence of diabetes and smoking, but there was a higher incidence of hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia in the MPS cohort (p<0.001).

The CTCA cohort

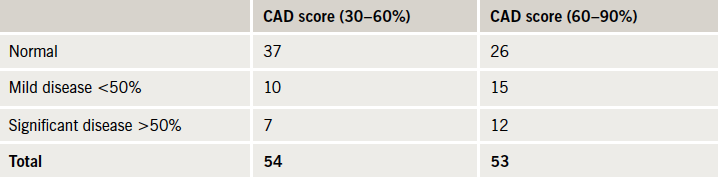

In the CTCA cohort, 107 had CTCA, of whom 54 had a CAD score of 30–60% and 53 had a CAD score of 60–90%. In total, 19 patients (17.9%) were found to have significant CAD (>50% stenosis) (table 2).

coronary angiography (CTCA) group

In the patients with CAD score 30–60%, seven patients had significant CAD (13.0%). Six of them went on to have further investigation, one had a positive MPS study, but did not attend his follow-up, three patients were investigated further with a DSE, which were negative and they were discharged, two were referred for ICA, and both were revascularised. In the 60–90% CAD score group, 12 patients had significant CAD on CTCA (22.6%), two had negative DSEs and were discharged. The other 10 were referred for ICA, seven of them proceeded to have revascularisation with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and one with coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). A total of 10 (9.4%) patients were revascularised in the CTCA cohort.

The functional test cohort

In the functional test cohort, 106 patients had functional tests: 39 had MPS, of which 12 patients were in the 30–60% CAD score group and 27 in the 60–90% CAD score group. In total, five patients (all in the 60–90% group) were found to have a positive result (12.8%) and all proceeded to have ICA. Four (10.3%) were revascularised with PCI.

There were 67 patients who underwent DSE, of which 29 were in the 30–60% CAD score group and 38 patients were in the 60–90% CAD score group. Only one patient (from the 60–90% CAD score group) was found to have significant reversible ischaemia, and went on to have ICA and was revascularised with PCI (1.5%). In total, five (4.7%) patients were revascularised in the functional test cohort. The higher revascularisation rate in the CTCA cohort of 9.4% was not statistically significant (p=0.28).

Six-month outcome

In total, three patients presented to accident and emergency (A&E) and were admitted for investigation of chest pain (1.4%). None of these three patients were deemed to have had a cardiac cause for chest pain and they were all discharged. There was no mortality at six months.

Discussion

The use of CTCA for the evaluation of chest pain in patients with moderate prevalence of CAD is well validated in three clinical trials that demonstrated very good sensitivity and excellent NPV.5-7 More recently, clinical trials from the USA demonstrated CTCA to be clinically effective, safe and economical compared with the current standard of care and MPS, in the emergency room.8-10

Our real-world data in a London district general hospital (DGH) demonstrate that CTCA can be at least as effective as functional tests in detecting significant CAD, and may lead to more revascularisations than functional tests. CTCA should be considered as an effective alternative to functional tests in patients with higher pre-test probability of CAD, in hospitals with limited access to functional tests. A further advantage of CTCA is that it can detect milder degrees of atherosclerosis, and these patients would benefit from secondary prevention.

Although functional testing is a test for ischaemia, and CTCA is an anatomical test, they are both used to rule out significant CAD in patients with chest pain. The NICE guidelines1 recommend the use of functional imaging tests in patients with moderate likelihood. However, the incidence of CAD in our population of patients with moderate and high likelihood appears to be relatively low. The NICE guidelines state that the CAD score is likely to overestimate risk in primary care populations and recommend that further research is needed in this area.1 CTCA is the best test available to rule out CAD with a NPV of 99% in published data,6 and, hence, we believe its use can be extended to patients with moderate and even high CAD scores. The estimated cost of a CTCA by NICE is £173, which compares well with the costs of DSE and MPS in the same costing report (£236 and £293, respectively).11 More importantly for busy clinical services, the advantage of CTCA over functional tests is its speed. The total time taken to perform a CTCA is less than 20 minutes per patient, which compares very well with DSE, MPS and cardiac magnetic resonance, all of which take around an hour per patient.

Although there were fewer MPS studies performed than DSEs, there were more positive studies in the MPS cohort (five vs. one), perhaps indicating physician preference to use MPS when they have a higher index of suspicion for CAD, thus, introducing a real-world selection bias. Our demographic data do demonstrate that the MPS cohort appeared to be older and have more risk factors.

The limitations of our study are those common to retrospective studies. Outcome data were obtained only from our hospitals’ notes, and any adverse events recorded in other hospitals would not have been automatically available. At six months, only three patients were re-admitted, all found to have non-cardiac chest pain. Not all patients underwent ICA, the gold standard for evaluation of CAD. Four patients were lost to follow-up, which represents 1.9% of the total study population.

In conclusion, we found CTCA to be at least as effective as functional tests in detecting significant CAD and may lead to more revascularisations than functional tests. Furthermore, our data demonstrate the CAD score to overestimate the probability of CAD in a RACP clinic population (table 2). Hence, we believe the use of CTCA can be extended to patients with moderate and even high CAD scores. Although CTCA is a low-cost test, a trend to higher revascularisation rate was also seen in the trials of CTCA in the emergency room.8,10 This may lead to an increase in the overall cost of managing CAD. A clinical trial is needed to evaluate the clinical effectiveness, as well as the cost-effectiveness, of using CTCA in patients with higher CAD scores.

Conflict of interest

There was no funding for this project and the authors have decared no conflict of interest.

Key messages

- The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) coronary artery disease (CAD) score is likely to overestimate risk in primary care populations

- Computed tomography coronary angiography (CTCA) is an excellent test for ruling out CAD in patients with low-to-moderate likelihood of CAD

- A clinical trial is needed to evaluate the clinical and cost-effectiveness of CTCA in patients with higher pre-test likelihood of CAD

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chest pain of recent onset. Clinical guideline 95. London: NICE, 2010. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/CG95

- Pryor DB, Shaw L, McCants CB, et al. Value of the history and physical in identifying patients at increased risk for coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med 1993;118:81–90.

- Rogers T, Dowd R, Yap HL, Claridge S, Alfakih K, Byrne J. Strict application of NICE clinical guideline 95 ‘chest pain of recent onset’ leads to over 90% increase in cost of investigation. Int J Cardiol 2013;166:740–2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.09.180

- Taylor AJ, Cerqueira M, Hodgson JM et al. ACCF/SCCT/ACR/AHA/ASE/ASNC/SCAI/SCMR 2010 appropriate use criteria for cardiac computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:1864–94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.005

- Budoff MJ, Dowe D, Jollis JG et al. Diagnostic performance of 64-multidetector row coronary computed tomographic angiography for the evaluation of coronary artery stenoses in individuals without known coronary artery disease. Results from the prospective multicentre ACCURACY trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:1724–32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.031

- Meijboom WB, Meijs MF, Schuijf JD et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 64 slice computed tomography coronary angiography: a prospective multicentre multivendor study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:2135–44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.058

- Miller JM, Rochitte CE, Dewey M et al. Diagnostic performance of coronary angiography by 64-row CT. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2324–36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0806576

- Litt HI, Gatsonis C, Snyder B et al. CT angiography for safe discharge of patients with possible acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1393–403. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1201163

- Goldstein JA, Chinnaiyan KM, Abidov A et al. The CT-STAT (Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography for Systematic Triage of Acute Chest Pain Patients to Treatment) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:1414–22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.068

- Hoffmann U, Truong QA, Schoenfeld DA et al. Coronary CT angiography versus standard of evaluation in acute chest pain. N Engl J Med 2012;367:299–308. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1201161

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chest pain of recent onset – costing report. London: NICE, 2011. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/12947/55738/55738.pdf