There was good news about the safety of a COX2 inhibitor, reduced bleeding with an oral anticoagulant and atheroma regression with a PCSK9 inhibitor at the American Heart Association (AHA) Scientific Sessions 2016, held in New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, from 12th–16th November 2016. We report on highlights from a few of the late-breaking clinical trials presented at the meeting, here and in our podcast online at

www.bjcardio.co.uk/podcasts/

PIONEER: rivaroxaban and antiplatelets reduce bleeding in AF post-PCI

A combination of two different strategies of the non-vitamin K oral antagonist, rivaroxaban, plus either mono or dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), significantly reduced the risk of clinically significant bleeding compared to standard triple therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

PIONEER AF PCI (Two Treatment Strategies of Rivaroxaban and a Dose-adjusted Oral Vitamin K Antagonist Treatment Strategy in Subjects with Atrial Fibrillation who Undergo Percutaneous Coronary Intervention) was an open-label, randomised, controlled, multicentre study, which randomised 2,124 patients to one of the three following arms:

- 15 mg rivaroxaban daily plus antiplatelet therapy (clopidogrel, prasugrel or ticagrelor) for 12 months (arm 1)

- 5 mg a “baby” dose of rivaroxaban twice daily for 1, 6 or 12 months at the investigator’s discretion plus dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin plus clopidogrel, prasugrel or ticagrelor) for 12 months (arm 2)

- standard triple therapy comprising the vitamin K antagonist (VKA), warfarin, plus dual antiplatelet therapy as in arm 2 for 12 months (arm 3).

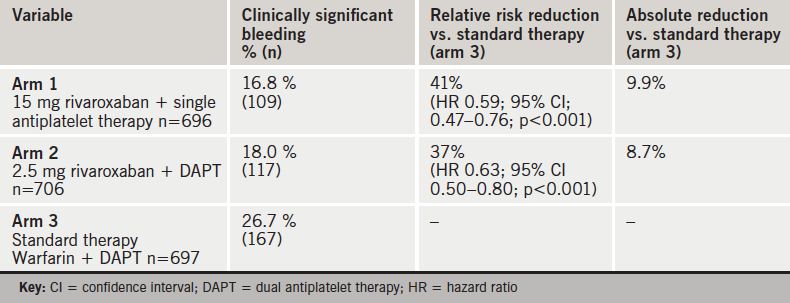

Principal results are shown in table 1. Rivaroxaban significantly reduced clinically significant bleeding (according to TIMI criteria) by 41% and 37% in arms 1 and 2, respectively, compared to standard triple therapy (arm 3).

Bleeding results were similar against other bleeding scales (ISTH , GUSTO and BARC).

Presenting the study at a late-breaking clinical trial session at the AHA, Principal Investigator, Dr C Michael Gibson (Harvard Medical School, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, USA) said that the results showed that to prevent one clinically significant bleed, you would need to treat 11 patients in the 15 mg rivaroxaban arm and 12 patients in the 2.5 mg rivaroxaban arm compared to standard triple therapy,

Results also showed that cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction and stroke were all similar in the three arms but no firm conclusions can be drawn from this as the study was not powered for statistical significance on efficacy.

A substudy looking at the risks of all-cause death or recurrent hospitalisation showed these were also reduced in both rivaroxaban arms. Risks were 34.9% in arm 1 and 31.9%, in arm 2, compared to 41.9% in arm 3.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) and coronary artery disease often occur together and Dr Gibson told the meeting that of the one billion people in Europe and the US, it is estimated that approximately 20 million (1–2%) will have AF, with 4.8 million also having coronary artery disease. Approximately 20–45% (1–2 million) of these will require PCI.

Discussant Dr Gabriel Steg (Hôpitaux de Paris, and Université de Paris, Paris, France) said PIONEER had made an “important and robust contribution to the currently limited evidence base available regarding AF and PCI”. It is one of the very few studies to address the issue of the optimal combination regimen of oral anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy. The study was “a huge step forward which will change treatment,” he said.

He said that the trial could not show if efficacy against stroke was preserved when using the reduced doses of rivaroxaban as it was underpowered for this end point. But Dr Gibson said the number of strokes that occurred during the study were few and “could be counted on an abacus”.

The study was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine on November 14th 2016 (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611594). The substudy was published in Circulation on November 14th 2016 (doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025783).

An editorial on the substudy by Dr Deepak Bhatt also published in Circulation (doi: CIRCULATIONAHA/2016/025923) said “From the PIONEER data to date, there seem to be significant benefits from abandoning the strategy of full dose triple therapy, with no apparent downside”.

He concluded: “For the time being, in patients not in clinical trials, full dose oral triple therapy with dual antiplatelet agents and full dose anticoagulation should be avoided as a routine practice.”

To find out more, watch our podcast from AHA.

PRECISION: cardiovascular safety of celecoxib the ‘same’ as ibuprofen and naproxen

The COX-2 inhibitor, celecoxib has been found to be non-inferior with regard to cardiovascular safety to two other widely used non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), ibuprofen and naproxen. Results from the study challenge the recent controversy over the cardiovascular safety of the COX-2 inhibitors after rofecoxib was withdrawn.

The PRECISION (Prospective Randomised Evaluation of Celecoxib Integrated Safety versus Ibuprofen or Naproxen) study set out to assess the non-inferiority of the cardiovascular risk of celecoxib (at a moderate dose) compared to naproxen and ibuprofen in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis patients.

The study randomised 24,081 patients in 926 centres to celecoxib (100 mg twice daily), ibuprofen (600 mg three times daily) or naproxen (375 mg twice daily) for a mean of 20.3 months with a mean follow-up of 34 months. Some 68.8% of patients stopped taking the study drug during the study and 27.4% of patients discontinued follow-up.

The primary end point was the Antiplatelet Triallists’ Collaboration (APTC) end point i.e. cardiovascular death (including haemorrhagic death), non-fatal myocardial infarction or non-fatal stroke, which was used to assess non-inferiority. Results in the intention-to-treat analyses (ITT) showed that a primary outcome event was reached by 2.3% (188) patients in the celecoxib group, 2.5% (201) of patients in the naproxen group and 2.7% (218) in the ibuprofen group.

Non-inferiority was also shown in the on-treatment analyses, which included events occurring only while patients are actually taking the drugs, compared to the ITT, which includes events after the patients stop therapy.

To assess comparative safety, superiority comparisons were also made for major adverse cardiovascular events, major gastrointestinal events, major renal events and hospitalisation for hypertension or chronic heart failure. Results showed the risk of gastrointestinal events was significantly lower with celecoxib than with naproxen (p=0.01) or ibuprofen (p=0.002). The risk of renal events was significantly lower with celecoxib than with ibuprofen (p = 0.004) but not significantly lower compared with naproxen (p = 0.19).

Principal investigator, Dr Steven E Nissen (Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, USA) at the meeting, who presented the study at the meeting, said the poor adherence and retention were a limitation of the study compared to most other studies to assess cardiovascular outcomes. He also pointed out that the dose of celecoxib used was moderate (100 mg twice daily), when previous trials that had suggested harm had studied much larger doses of the drug (up to 800 mg daily).

Discussant of the study, Dr Elliott Antman (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, USA) said, following presentation of the results: “I am repositioning my opinion on where celecoxib sits”, although he asked how we could interpet the cardiovascular, renal and gastrointestinal effects when 69% of patients discontinued therapy?

He noted though that the trial had been set up with the hope that it would give us information on the safety of NSAIDs. “What we have learned,” he said “was that cardiovascular safety profiles were essentially the same”.

The PRECISION study was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine on November 13th 2016 (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611593).

But in a review of the study in Circulation published the same day, (doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026324), Dr Garrett A Fitzgerald (Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Phildadelphia, USA) writes: “There are so many problems with the interpretation of PRECISION that it fails to inform clinical practice”.

GLAGOV shows atheroma regression with evolocumab

Adding the protein convertase/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor, evolocumab, to optimised statin therapy for low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) lowering resulted in significant regression of coronary atheroma volume in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), according to results from the GLAGOV (GLobal Assessment of Plaque Regression with a PCSK9 Antibody as Measured by Intravascular Ultrasound) study.

The phase 3 imaging trial was presented by Dr Steven E Nissen (Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, USA) at the meeting and simultaneously published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16951).

In the study, 968 statin-treated CAD patients at 197 sites globally were randomised in a 1:1 ratio for 78 weeks to either evolocumab (420 mg monthly administered monthly by subcutaneous injection) plus statins or placebo (statin monotherapy). Patients underwent an intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) examination of a single coronary artery during a clinically-indicated angiogram at baseline, followed by a repeat IVUS examination of the initially-studied vessel at 78 weeks.

The study met its primary efficacy endpoint – the change in per cent atheroma volume (PAV) from baseline to 78 weeks post-randomisation as measured by IVUS – with evolocumab producing a significant reduction in PAV of almost 1% (-0.95%) versus baseline compared with placebo where PAV did not change (+0.05%) (p<0.001 vs. baseline; between-group difference, -1.0% ; p<0.001 vs. placebo).

Secondary efficacy end points included the nominal change in normalised total atheroma volume (TAV) from baseline to 78 weeks post-randomisation and the percentage of patients demonstrating regression.

A significant reduction in TAV was seen (0.9 mm3 decrease with placebo and 5.8 mm3 decrease with evolocumab (difference, -4.9 mm3; P<0.001). In addition, 64.3% of patients taking evolocumab plus statin had coronary atherosclerotic regression compared with 47.3% of patients taking statin alone (difference, 17.0%, p<0.001).

There was an 87% retention rate and no new safety concerns were identified; the overall safety profile of evolocumab was comparable to that of control.

Dr Nissen said that it appeared that people with the lowest LDL-C levels (< 70 mg/dL at baseline) had more regression – around a 2% decrease in volume – compared to those taking a statin alone. “I am very encouraged that LDL is a waste product and there is no evidence that any LDL will be too low,” he said.

While the findings from the current trial are promising, further studies are needed to assess the effects of PCSK9 inhibition on cardiovascular outcomes. The first such study with evolocumab, FOURIER, (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01764633) will report next year.

EUCLID – ticagrelor and clopidogrel of equal benefit in PAD

In patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease (PAD), ticagrelor was not shown to be superior to clopidogrel for the reduction of preventing cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or ischaemic stroke according to findings from EUCLID (Examining Use of Ticagrelor in Peripheral Artery Disease), the largest ever PAD study.

Findings from this double-blind, event-driven trial, were presented at the meeting by Dr Manesh Patel (Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina, USA) and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611688).

PAD currently affects 200 million people worldwide. In the study, 13,885 patients with symptomatic PAD (median age 66 years, 72% men) were randomly assigned to receive monotherapy with either ticagrelor (90 mg twice daily) or clopidogrel (75 mg once daily). Patients were eligible if they had an ankle–brachial index (ABI) of 0.80 or less or had undergone previous revascularisation of the lower limbs. Some, 76.6% of the patients had claudication, and 4.6% had critical limb ischaemia. The median follow-up was 30 months.

Results showed that the primary efficacy end point – a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or ischaemic stroke – occurred in 10.8% of patients (751/6,930) receiving ticagrelor and in 10.6% (740/6,955) receiving clopidogrel (p = 0.65). In each group, acute limb ischaemia occurred in 1.7% of the patients (p = 0.85) and major bleeding in 1.6%; p = 0.49). The only significant between-group difference was the rate of ischaemic stroke, which was 1.9% for ticagrelor and 2.4% clopidogrel (p=0.03).

The primary safety end point was major bleeding. While each drug was associated with similar rates of major bleeding, ticagrelor was discontinued more frequently than clopidogrel because of the occurrence of side effects (mainly dyspnoea and minor bleeding).

Commenting on the results, discussant, Dr Carl Pepine (University of Florida Health, Gainesville, Florida, USA) described them as “surprising”. While ticagrelor was not superior to clopidogrel in reducing events, there was a “very interesting signal for stroke reduction”, which he suggested may be in part attributable to ticagrelor blood pressure lowering.

Registry shows higher mortality with TAVI versus conventional surgery in severe aortic valve stenosis

Registry data has shown that one-year mortality rates for patients receiving transcatheter aortic-valve implantation (TAVI) for severe aortic valve stenosis were found to be significantly higher than those observed in patients receiving conventional surgical aortic valve repair (SAVR).

The results – from the prospective GARY (German Aortic Valve Registry) study – were presented at the AHA by Dr Nicolas Werner (Medical Clinic B, Klinikum Ludwigshafen, Germany). TAVI is currently the recommended treatment option for patients with severe aortic valve stenosis, who are inoperable or at high surgical risk. The earlier PARTNER II study had shown TAVI to be non-inferior to SAVR in terms of mid-term mortality and disabling stroke in a selected population of patients at intermediate surgical risk.

GARY compared clinical characteristics and outcome in an ‘all-comers’ clinical population at intermediate surgical risk undergoing isolated TAVI or SAVR for severe aortic valve stenosis in clinical practice today. It included all consecutive patients undergoing an invasive aortic valve therapy for acquired aortic-valve disease comprising 87% of all aortic-valve procedures performed in Germany between 2011 and 2013. In all, there were 5,997 evaluable patients (SAVR n = 1,896, mean age 72 years; TAVI n = 4101, mean age 82 years), all with severe symptomatic aortic-valve stenosis (grade III or IV).

Results showed the one-year all-cause mortality was lower with SAVR (8.9%) than with TAVI (16.6%) (p < 0.001). An adjusted comparison propensity-score analysis of the one-year mortality rates still showed higher mortality rates for TAVI compared with SAVR (15.25% vs. 10.89%, respectively; p = 0.002).

The TAVI patients, however, had more severe disease/comorbidities at baseline, and were older, more likely to be New York Heart Association (NYHA) grade III or IV, have prior myocardial infarction, pulmonary hypertension, atrial fibrillation, mitral regurgitation grade ≥2, a permanent pacemaker, and creatinine >2 mg/dl. Among patients treated with TAVI, age was cited as the indication for the surgery in 77.2% and frailty in 47.3%.

Dr Werner concluded that intermediate surgical risk patients undergoing isolated TAVI in a real-world scenario have a low in-hospital mortality rate (< 4%). Even after propensity score analysis, a significant difference in one-year mortality rate persisted between the two patient groups, most probably caused by additional confounders. In PARTNER II there was non-inferiority of TAVI compared to SAVR in a selected intermediate-risk population. In contrast, GARY showed “clinical reality and a reasonable selection of patients in everyday clinical practice”.

Cardiac surgeon, Dr Craig Smith, NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Medical Center, New York, the discussant for the presentation, said, “the overall risk here was lower than in PARTNER II, especially in the surgical group, so it’s hard to make comparisons. There was excellent mortality in both groups, and the stroke rate was similar to PARTNER II.” The site-dependent effects were potentially “very confounding”, however, he said.

In briefs from the meeting

- The heart attack toll with Hurricane Katrina

Ten years after the devastating Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in August 2005, a single-centre study, presented at the meeting from Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, has shown that myocardial infarction admissions in the city were three times higher than they were before the storm.

The study also identified additional potential health problems among the post-storm group versus their pre-Katrina counterparts. They were more than twice as likely to abuse drugs and/or to have a psychiatric disease; unemployment and a lack of health insurance were significantly more frequent; they were more likely to receive prescriptions for cardiac medications and for treatment of dyslipidaemia and hypertension; and they were only half as likely to take their medication, compared to the pre-Katrina group.

- HOPE 3: cognitive impairment and dementia not slowed

Two interventions thought likely to have a positive effect on cognitive impairment and dementia – blood-pressure lowering and treatment with statins – surprisingly did not prevent cognitive and functional decline.

These were the main results from the HOPE 3 (Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaulation) study, which looked at these two interventions in 12,705 elderly patients at intermediate risk for cardiovascular events and followed up for 5.6 years. The results did show, however, that treatment with statins (rosuvastatin) had no adverse effect on cognitive decline.

- ART shows no differences in clinical outcomes with bilateral grafts

Better graft patency is expected to equate to improved survival but the five-year interim results from ART (Arterial Revascularisation Trial) failed to show any benefit with bilateral grafting. The study compared bilateral versus single mammary grafts in 3,102 patients with symptomatic multi-vessel coronary artery disease, who were randomised to either group and followed up for five years.

No significant differences were shown in all-cause mortality; a composite of mortality, myocardial infarction or stroke; major bleeds, need for repeat revascularisation, angina status and quality of life measures. There was also an early excess of sternal wound complications with bilateral mammary graft. The longer term results at 10 years, however, will determine whether there is any difference in the two approaches.

- AEGIS-I: phase 2 study shows HDL raising may lead to benefit

A ray of hope for the benefits of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) raising has been shown in the phase II AEGIS-I (ApoA-I Event Reducing in Ischaemic Syndromes I) study. The compound CS112 – derived from ApoA-I, the major constituent of HDL – has been found to elevate cholesterol efflux capacity in a dose-dependent fashion. Efflux is the first stage of reverse cholesterol transport, where HDL transports excess cholesterol to the liver for removal from the body. A phase III study is now being planned.

To find out more, watch our podcast from AHA.