Refractory angina represents an important clinical problem. Spinal cord stimulation (SCS) for refractory angina has been used for over two decades to improve pain and, thus, quality of life. This case series reports the clinical efficacy and safety profile of SCS.

We included patients who had a SCS device implanted between 2001 and 2015 following a rigorous selection process. Patients were prospectively followed. We performed a descriptive analysis and used paired t-test to evaluate the difference in Canadian Cardiovascular Society angina (CCS) class before and after SCS implant.

Of the 100 patients included, 89% were male, the mean age was 65.1 years and mean follow-up time was 53.6 months. The CCS class after SCS implant was statistically improved from before (p<0.05) and 88% of patients who gave feedback were very satisfied. Thirty-two patients died, 58% of those who had a documented cause of death, died from a non-cardiac cause.

This study shows the outcome of 14 years’ experience of SCS implantation. The anginal symptoms had a statistically significant improvement and the satisfaction rate was higher than 90%. The complication rate is within the range reported in the literature. SCS seems to be an effective and safe treatment option for refractory angina.

Introduction

Spinal cord stimulation (SCS) therapy has been used for more than four decades in a variety of chronic pain conditions. The introduction of neurostimulation was a logical consequence of the ‘gate-control’ theory published in 1965.1 According to this model, the activation of large afferent nerve fibres inhibits pain input mediated by small fibres into the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. The goal of SCS is to attenuate discomfort by provoking paraesthesia in the same area.

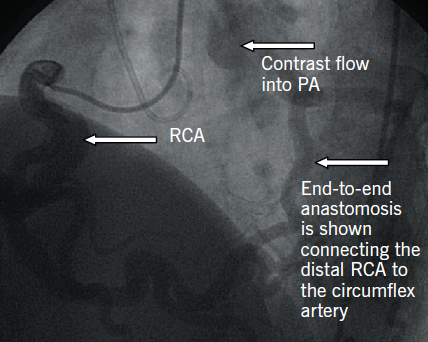

The European Society of Cardiology defines refractory angina as a chronic condition characterised by the presence of angina caused by coronary insufficiency in the presence of coronary artery disease, which cannot be controlled by a combination of medical therapy, angioplasty and coronary bypass surgery.2 This condition represents an important clinical problem with an incidence of 100,000 new cases per year in Europe.3 The presence of reversible myocardial ischaemia should be clinically established to be the cause of the symptoms. Chronic is defined as duration of more than three months.4 Many of these patients have already had coronary surgery and percutaneous coronary interventions. These patients have reversible ischaemia yet the coronary vessels are not amenable to surgery or stenting. SCS for refractory angina has been used for over two decades. This treatment does not improve disease progression, but is used in a palliative mode, by improving the pain symptoms and quality of life. The detailed mechanisms of action of SCS for refractory angina are complex, as it may improve coronary perfusion, in addition to attenuating pain signals. Interestingly, the majority of the refractory angina patients have been diagnosed with this condition, but cannot be offered a good estimate of survival, as the prognosis is very variable.

The increasing success of traditional treatment methods to treat coronary events has led to an improvement in survival rate of these patients and, as a consequence, to an increase in the number of patients presenting with refractory angina.

Randomised-controlled trials5-10 have shown an improvement in symptoms (daily angina attacks or Canadian Cardiovascular Society angina class) after the use of SCS. Most trials have also shown a statistically significant improvement in quality of life,5,6,8,9 as pointed out by Tsigaridas et al. in their recent systematic review.11

The aim of this study was to assess the clinical improvement of our patients, as well as to evaluate the safety of SCS by analysing the complications, long-term survival, cause of death and satisfaction with treatment, in our centre.

Methods

This study included all patients who had an SCS device implanted for refractory angina, from January 2001 to September 2015, and were prospectively followed-up in the pain clinic of a tertiary referral centre for cardiovascular disease. The treatment is offered as part of a refractory angina national programme. All patients were assessed by a multi-disciplinary team to ensure that there were no further opportunities for revascularisation, either surgically or percutaneously. All patients were on optimal medical therapy, as tolerated. Some of the referred patients are offered further surgical or percutaneous revascularisation, some are offered cardiac surgery, and some are optimised with medical therapy. Patients not suitable for any of these options were then assessed with an extensive psychological questionnaire, prior to being considered for SCS implantation.

Patients

At the time of implantation, Canadian Cardiology Society (CCS) class III/IV symptoms were present despite maximal medical therapy in all patients. All patients had documented obstructive coronary artery disease, reversible myocardial ischaemia, and were not suitable for further surgical or percutaneous coronary artery revascularisation.

Procedure

After informed consent, the implantation of a SCS system was undertaken in an operating theatre under fluoroscopic guidance. All procedures from 2001 to 2011 were undertaken by two operators (one cardiologist and one anaesthetist). All procedures from 2011 to 2015 were undertaken by a single operator (anaesthetist). All operators were trained in the technique at Gottenburg, a recognised leading centre for SCS implantation. All patients received Medtronic SCS systems with a quad lead, connecting lead and IPG (implantable pulse generator – ITREL III, followed by Synergy, followed by ITREL IV, in time). The epidural space was located at the level of T4–T6 using a right paramedian approach, and a single electrode lead was advanced up to C5–C6, slightly to the left of midline, under fluoroscopic guidance. The final location was adjusted up to the level where the activation of the stimulator evoked paraesthesiae, which covered the area of the anginal pain. The leads were then connected through extension cables tunnelled subcutaneously to the pulse generator, implanted in the subcostal area. The programming of the SCS was done by one of two experienced cardiac pacing technicians, who also performed all follow-up checks and reprogramming sessions. The implantation was always completed in a single sitting. Patients were observed overnight as inpatients and discharged home on the following day, with post-operative instructions to wear a soft neck collar, and to take five days of antibiotic prophylaxis. Patients were advised to continue the same anti-anginal medication to allow accumulative prognostic benefit. As the success rate is very high in this patient group, all patients received a short trial of electrical stimulation on the operating table, and had the permanent system implanted at the same sitting.

The patients were instructed to use the SCS for one hour three times per day, in addition to stimulation during angina attacks and before physical activities that would otherwise cause angina pain.

Surgery for mechanical lead problems and IPG replacements took place in the same style, under local anaesthesia and in an operating theatre.

Post-operative assessment

These patients were routinely reviewed in a follow-up clinic at one month after implantation and every year thereafter. If there were problems with the device or programming, the outpatient reviews were more frequent. If there were low energy readings of the IPG, the reviews were reduced to six monthly.

We reviewed the patients’ files to obtain the following data: time of implant, previous cardiac surgery, symptom severity before and after the SCS, failure or complications, time of follow-up, satisfaction with SCS treatment, and cause of death, when applicable. When the data were incomplete, we conducted a telephone consultation with the patient to assess symptom severity after the SCS and degree of satisfaction with the treatment (‘very dissatisfied’, ‘dissatisfied’, ‘unsure’, ‘satisfied’, ‘very satisfied’). Telephone calls were also made to general practitioners to determine cause of death when it was not clear from patients’ files.

Ethics and statistical analysis

Local Ethics Committee approval was sought and the study approved.

Numerical variables were tested for normality, and results are shown as mean and standard deviation (SD).

Data from CCS class was recorded before SCS implant and at the most recent follow-up. To test if the difference between CCS classes before and after SCS implant was significant, we used a paired t-test with a significance level of p<0.05.

Results

Patients

One hundred patients were identified, of whom 89 (89%) were male and the mean age at the time of SCS implant was 65.1 years (SD 8.34 and range 44.4–86.5). In this group of patients, 89% had previous cardiac surgery for ischaemic heart disease.

Mean follow-up time was 53.6 months. In our sample, 32 patients died during the follow-up period and one patient was lost from follow-up.

Effect on symptoms

Data regarding the effect on symptoms was obtained from 68 patients (68%), seven of these are from patients who have subsequently died. From the patients that are still alive, we lack data from six (9%) of them because their devices were explanted, and from one other patient that was lost to follow-up. The majority of these patients received SCS early in the programme (five patients had explants 2001–2007, and one patient in 2013).

Before SCS implantation, the mean value for CCS class was 3.1 (0.8) and, at the latest follow-up, it was 2.0 (0.7). The mean difference between these two was 1.0 (0.97) and it was statistically significant at p<0.05 (p=0.00001).

From the 68 patients alive, 67 gave feedback regarding satisfaction, 59 (88%) were very satisfied, two (3%) were satisfied, and six (9%) were dissatisfied (those whose devices were explanted). Of all IPGs used (ITREL III, Synergy, ITREL IV) during the study period 14 needed replacement. The mean time, in years, that the batteries lasted was 8.4 (2.2).

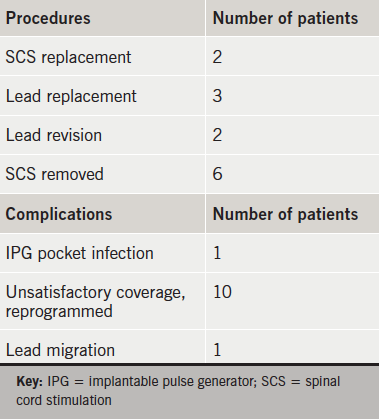

Complications

Procedures and complications are listed in table 1.

The two cases of SCS replacement were due to failure and infection. Of the three lead replacements, two were done because of casing breakage (8–10 years after implantation), and one because of surgical damage during IPG replacement. Of the two lead revisions, one was done for poor initial position and the other for infection. The case of infection in IPG pocket resolved after one week of antibiotics and later on, the patient was implanted with a new SCS.

The only case of epidural lead infection was in a female patient in whom the brassiere catch had eroded the skin in the area of T5/T6 within a month after implantation. This was treated with antibiotics, and the wound revised. The patient changed the brassiere type and there were no further problems.

Explants were due to inadequate pain control or patient discomfort. In one patient the implantation of SCS up to C5 produced constant nausea, even after switching the device off. The symptoms of angina had completely disappeared. A large renal tumour was diagnosed and removed, but the patient progressed to stage 3 renal failure. After one year of use, the device was explanted and the patient followed-up for a further year.

Fourteen patients had IPG replacement during this period (IPGs used were not rechargeable).

Cause of death

Considering the 32 patients who died during follow-up, 12 (37.5%) have a documented cause of death in either the GP’s records or ours. Seven (58%) of these patients died from a non-cardiac cause, for example cancer, accident, stroke or infection. The other five (42%) died of myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure or sudden collapse.

Prior to death, the mean duration of SCS use for this group of patients was 44 months.

Discussion

This study shows the outcome from 14 years of experience implanting SCS for refractory angina. We present data from a single cardiothoracic centre with refractory angina patients assessed by a multi-disciplinary team. Only selected patients, not suitable for revascularisation and with documented reversible ischaemia, were considered for SCS. Over the last 14 years, 100 SCS were implanted.

Our results show that SCS implantation produces a statistically significant improvement in angina symptoms. The effect of SCS on pain control was previously reported,5-10 using number of angina attacks and CCS class with different types of stimulation. However, the number of randomised-controlled trials (RCTs) is small, as is the number of patients included in each of them. This may be due to the strict inclusion criteria for RCTs. Additionally, given the invasive nature of the procedure for SCS implantation and the effect of paraesthesia produced by the stimulation, it is difficult to have patients blinded in these studies.

Even though we did not have a comparison group, we were able to compare the severity of the angina at two different time-points. Each subject acted as their own control. Additionally, our sample was bigger than each of the studies analysed in the recent systematic review,11 when taken separately.

More than 90% of the patients were satisfied or very satisfied with the SCS treatment.

Our rate of complications is within the range reported in different studies.7,9,10,12,13 Reprogramming solved the unsatisfactory coverage. However, there were six patients who requested removal of SCS for inadequate pain control or discomfort. These were the patients who were dissatisfied with the treatment.

Of our patients, 32% died during follow-up, none of these deaths were related to the SCS implant and less than half of them died from a cardiac cause, where the cause of death was known. Although we aimed to find out the cause of death and, hence, whether the patients died from non-cardiac pathology, this task proved to be particularly difficult and we could not draw any conclusions.

The death rate of patients with SCS implantation in our centre is higher than previously reported,6,7,12,13 which might be due to a highly selected sample in our centre that is referred to the pain clinic by cardiologists, only when all other treatment options have been utilised.

Although this study has the advantage of reporting the experience from a single centre with a good sample size, it also has some limitations. Among them are:

- There are incomplete records from a few patients, namely regarding pain severity after SCS in the deceased and their cause of death.

- Lack of information regarding additional therapy.

- Patients who requested removal of SCS were not considered for the analysis of pain severity after SCS implant, which might overestimate the effect of SCS.

In conclusion, SCS appears to be an effective and safe treatment option with a low complication rate in the management of refractory angina patients. This treatment is recommended by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC),2 American Heart Association (AHA), and six more associations,14 as a class IIb recommendation with a level of evidence B and C, respectively. Detailed patient assessment for suitability for SCS and post-implant follow-up by an experienced team offer good patient satisfaction rates.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Key messages

- Spinal cord stimulation (SCS) is used for refractory angina and improves pain symptoms and quality of life

- There is a statistically significant decrease in angina pain class with SCS

- SCS appears to be an effective and safe treatment option with a low complication rate in the management of refractory angina patients

- Detailed patient assessment for suitability for SCS and post-implant follow-up by an experienced team offer good patient satisfaction rates

References

1. Melzack, R, Wall PD. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science 1965;150:971–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.150.3699.971

2. Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2949–3003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht296

3. Mukherjee D, Bhatt DL, Roe MT et al. Direct myocardial revascularization and angiogenesis – how many patients might be eligible? Am J Cardiol 1999;84:598–60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9149(99)00387-2

4. Mannheimer C, Camici P, Chester MR et al. The problem of chronic refractory angina; report from the ESC Joint Study Group on the Treatment of refractory Angina. Eur Heart J 2002;23:355–70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/euhj.2001.2706

5. Eddicks S, Maier-Hauff K, Schenk M et al. Thoracic spinal cord stimulation improves functional status and relieves symptoms in patients with refractory angina pectoris: the first placebo controlled randomized study. Heart 2007;93:585–90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2006.100784

6. Lanza G, Grimaldi R, Greco S et al. Spinal cord stimulation for the treatment of refractory angina pectoris: a multicenter randomized single-blind study (the SCS-ITA trial). Pain 2011;152:45–52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.044

7. Zipes D, Svorkdal N, Berman D et al. C. Spinal cord stimulation therapy for patients with refractory angina who are not candidates for revascularization. Neuromodulation 2012;15:550–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1403.2012.00452.x

8. Di Pede F, Zuin G, Giada F et al. A. Long-term effects of spinal cord stimulation on myocardial ischemia and heart rate variability: results of a 48-hour ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring. Ital Heart J 2001;2:690–5.

9. de Jongste MJ, Hautvast RW, Hillege HL, Lie KI. Efficacy of spinal cord stimulation as adjuvant therapy for intractable angina pectoris: a prospective, randomized clinical study. Working Group on Neurocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994;23:1592–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0735-1097(94)90661-0

10. Hautvast RW, DeJongste MJ, Staal MJ, Gilst WH, Lie KI. Spinal cord stimulation in chronic intractable angina pectoris: a randomized, controlled efficacy study. Am Heart J 1998;136:1114–20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0002-8703(98)70171-1

11. Tsigaridas N, Naka K, Tsapogas P et al. Spinal cord stimulation in refractory angina. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Cardiol 2015;70:233–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.2143/AC.70.2.3073516

12. Mannheimer C, Eliasson T, Augustinsson LE et al. Electrical stimulation versus coronary artery bypass surgery in severe angina pectoris: the ESBY study. Circulation 1998;97:157–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.97.12.1157

13. McNab D, Khan SN, Sharples LD et al. An open label, single-centre, randomized trial of spinal cord stimulation vs. percutaneous myocardial laser revascularization in patients with refractory angina pectoris: the SPiRiT trial. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1048–53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehi827

14. Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J et al. American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 2012;126:354–471. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0b013e318277d6a0