A discharge summary is intended to communicate relevant clinical information to GPs after hospital admission. High-quality discharge summaries are especially important in complex clinical syndromes, such as chronic heart failure, where effective communication between multi-disciplinary teams is necessary to coordinate safe community care and reduce re-hospitalisation risk.

The aim of this study was to audit the existing quality of heart failure discharge summary documentation at our Trust and test whether a 10-point checklist poster could improve performance. All heart failure discharge summaries issued from Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospitals’ NHS Trust over a three-month period were assessed. The content of each heart-failure-verified discharge summary was objectively analysed using a points-based scoring technique. A single checklist poster providing guidance on composing heart failure discharge summaries was positioned in a medical ward. The scores from every summary issued by doctors exposed to the checklist poster (n=24) on that ward were compared against discharge summaries scores issued by doctors working on all other (non-exposed) wards (n=84).

Of discharge summaries with heart failure listed as a primary diagnosis, 28% were found to have an alternate cause for symptoms and no verifiable evidence to support a heart failure diagnosis. Discharge summaries issued by doctors working on the ward exposed to the checklist poster had a mean discharge summary score of 5.2 ± 0.59. Discharge summaries issued by doctors working on wards that were not exposed to the checklist poster had a mean score that was significantly poorer 1.7 ± 0.11 (p<0.001).

This study demonstrates that a primary heart failure diagnosis may be inaccurate in approximately a quarter of all discharge summaries. The provision of a 10-point checklist was associated with a statistically significant improvement in the quality of heart failure discharge summaries issued from our Trust. This intervention was simple to implement at minimal cost and helps junior doctors communicate more effectively with primary care.

Introduction

Hospital doctors have a professional responsibility to complete an accurate and comprehensive discharge summary with relevant clinical details. It is fundamental that any healthcare professional supporting the aftercare of a heart failure patient is briefed on the diagnosis, clinical progress, treatment and follow-up arrangements following hospitalisation.

The purpose of a discharge summary is to share important clinical information about a patient’s hospital episode with their GP and other healthcare professionals responsible for providing continuing care. However, discharge summaries often fail to communicate effectively.1 In 2013, the Royal College of Physicians published general professional standards for patient healthcare records providing an overview of the requirements for a discharge summary.2

A detailed discharge summary is especially important in heart failure where management may be very complex due to: comorbidities, frailty, involvement of multi-disciplinary teams, chasing results of multiple investigations, patients’ variance in tolerance to treatments, long hospital stay and high rates of readmission.

Aim

The aim of this study was to audit the existing quality of heart failure discharge summary documentation at our Trust and test whether a 10-point checklist poster (providing specific guidance on what to include when composing an optimal heart failure discharge summary) could improve performance.

Methods

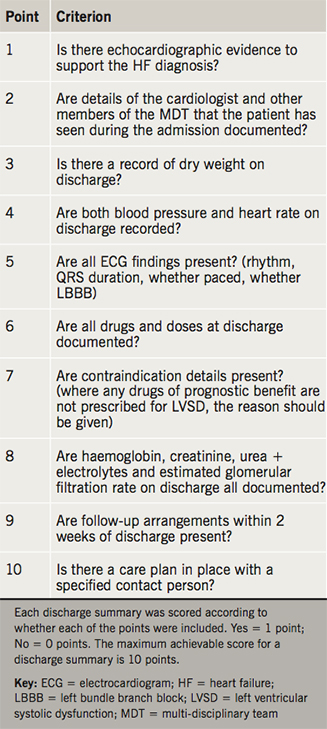

There is currently no national standard for determining a good quality heart failure discharge summary, nor established metrics on how to assess it. In 2015, the Heart Failure Improvement Collaborative (funded by University College London Partners and Chaired by Dr Simon Woldman, Consultant Cardiologist and Clinical Director Specialist Cardiology, St. Bartholomews Hospital, London) compiled a checklist of items considered necessary for inclusion in a comprehensive heart failure discharge summary. This work was the culmination of an extensive multi-disciplinary committee discussion, involving local consultant cardiologist leads in heart failure, GPs and heart failure specialist nurses. Though not exhaustive, the (unpublished) list was, by consensus, felt to concisely address the key requirements of clinicians, patients and carers involved in the post-hospital care of heart failure patients. This list was made available free of charge and offered an idealised standard against which discharge summary content could be audited.

An adapted version of this checklist was used as a template tool for quantifying the quality of discharge summary documentation (table 1). Each discharge summary was scored by the assessor, according to how many of the checklist key points were recorded within the text (one point for each key item present). Total points for each summary were summated to arrive at a maximum achievable score of 10. As every discharge summary issued by our Trust mandatorily includes the drugs and doses at discharge, the minimum achievable score was 1. For the purposes of our study, a higher score out of 10 would be interpreted as a better quality discharge summary. This scoring system enables an unbiased, reproducible and objective means of assessing the quality of a discharge summary.

The quality of heart failure discharge summaries issued by the two acute district general hospitals (King George Hospital, Goodmayes, and Queens Hospital, Romford) within our Trust was assessed. Consecutive discharge summaries following unplanned hospital admissions with a primary diagnosis of heart failure were identified over a three-month period (23 October 2014 to 22 January 2015) using Hospital Episodes Summary data. Electronic discharge summaries and clinical notes were reviewed by a consultant cardiologist to ensure that the primary diagnosis of heart failure was correct, robust and verifiable (i.e. corroborated by history, symptoms, signs and imaging investigations).

In order to test whether our proposed intervention could be associated with improved discharge summary documentation, a single poster incorporating the checklist was placed in the junior doctors’ office adjacent to computers used for composing electronic discharge summaries. Clinicians would, thus, be able to view and refer to the checklist during electronic discharge summary composition. The cardiology ward at King George Hospital was the only ward displaying the heart failure discharge summary checklist poster. The doctors on the remaining cardiac and non-cardiac wards across the rest of the Trust were never exposed to the checklist poster.

The discharge summary scores between the doctors working on the ‘exposed’ ward (i.e. the ward displaying the discharge summary checklist poster) versus all the other ‘non-exposed’ wards (which included a mix of cardiac and non-cardiac wards across the two hospitals in the Trust) were compared. The discharge summary scores were checked for Gaussian distribution using a Shapiro-Wilk test, and the Mann-Whitney U-test was applied to assess for statistically significant differences in the mean discharge summary scores.

Results

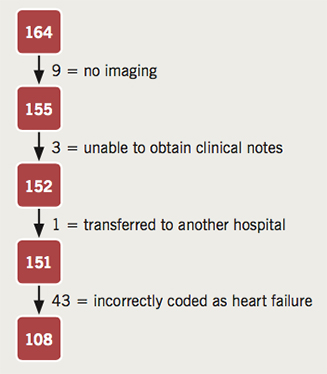

In total, 164 individual patient episodes were identified from Hospital Episode Summary data as being discharged between 23 October 2014 and 22 January 2015. Thirteen patients were excluded: nine had no diagnostic imaging to verify a diagnosis of heart failure. Clinical notes could not be obtained for three patients. One patient was transferred as an inpatient to another Trust and ultimately discharged by that Trust. This is graphically displayed in figure 1.

The remaining 151 patient episodes had a review of the clinical notes, imaging and electronic discharge summaries by a consultant cardiologist. There were 43 patients (28%) found not to have a primary diagnosis of heart failure after specialist review of case notes. In these cases, the clinical notes, blood tests, radiological and echocardiographic evidence supported an alternate non-cardiac cause for the admission. Alternate diagnoses incorrectly coded as heart failure included: chest infection/pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary fibrosis, fluid overload secondary to chronic lymphoedema, chronic kidney disease/nephrotic syndrome and chronic liver disease.

Each of the heart-failure-verified discharge summaries (n=108) across the two acute district general hospitals in the Trust were assessed using the 10-point scoring system.

In the ward exposed to the discharge summary checklist, the mean discharge summary score was 5.2 ± 0.59 (standard error of the mean [SEM]) – scores ranged from 1 to 10. In the wards that were not exposed to the checklist, the mean discharge summary score was 1.7 ± 0.11 (SEM) – scores ranged from 1 to 5. These data are highlighted in figure 2. These results demonstrate that exposure to the discharge summary checklist poster was associated with a highly statistically significant improvement in discharge summary score (p<0.001).

Discussion

Our clinical records analysis found that more than a quarter of patients were incorrectly coded/diagnosed as heart failure. Heart failure is common, but several other common medical conditions can mimic the non-specific signs and symptoms of heart failure risking misdiagnosis. An inaccurate diagnosis or miscoding of heart failure is not benign and can have serious consequences for both patients and hospital reimbursement. Being labelled with a chronic and potentially fatal diagnosis of heart failure can have an adverse psychological impact on the patient. It can also misdirect clinical management by doctors with wrongful treatment, denial of potential life-saving access to intensive care, harm from inappropriate medication and failure to investigate the true cause of the patient’s symptoms. It is, therefore, crucial that clinicians be mindful of ‘over-diagnosing’ patients with heart failure when the history, clinical signs and investigations do not support it.

Writing discharge summaries is traditionally undertaken by junior doctors. Lack of formal training, supervision and feedback in discharge summary composition can result in errors and omissions occurring commonly. Most omit several important clinical details, which are necessary for safe continuity of care.3 This highlights a clear need for intervention in order to improve the quality of heart failure discharge summaries. However, this can be difficult to achieve with time pressures on junior doctors, and there may not be sufficient resources within the Trust to provide formal training and supervision in writing high-quality discharge summaries. A simple checklist poster placed in the doctors’ office can offer a source of reference and support to the junior doctor writing a summary.

Almost a quarter of patients who are discharged following a hospitalisation due to heart failure are readmitted within 30 days.4 Discharge summaries aim to provide a line of communication between hospital clinicians and those involved in follow-up in the community. A good quality heart failure summary may be associated with lower 30-day readmission.5

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is that it is a relatively small-scale, observational study testing the efficacy of a discharge summary checklist. There is no standardised national model or metric for auditing the quality of discharge summaries in a reproducible way.

We cannot be certain that every doctor completing a discharge summary in the poster-exposed ward had actually noticed or used the checklist poster. Discharge summaries can be written by several different grades of junior doctors with variable knowledge or experience of the complexities of heart failure and with variable time pressures on how long they have to compose their discharge summary. All of these points are potential confounding factors, which could have influenced the outcome of this study.

Key messages

- Discharge summaries often lack key details – using a checklist can improve the content and quality of a heart failure discharge summary

- A good-quality discharge summary is especially important in complex clinical syndromes where effective communication with the GP is necessary to coordinate community care

Conclusion

The overall standard of discharge summaries written without the benefit of a checklist was found to be very poor. More than a quarter of discharge summaries for heart failure had an incorrect primary diagnosis and important clinical details were often omitted.

Our study supports the provision of a checklist for junior doctors composing heart failure discharge summaries, as it can improve the quality of documentation. A simple checklist intervention is cost-effective and straightforward to implement. It has the potential to have a large impact on discharge summary quality. A high-quality discharge summary can facilitate comprehensive discharge planning and potentially contributes to improved post-hospital care.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank UCL Partners, London, for supplying the checklist and acknowledge Dr Christos Bourantas for conducting statistical analysis.

Sources of funding

No sources of funding to declare.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

1. Al-Damluji MS, Dzara K, Hodshon B et al. Hospital variation in quality of discharge summaries for patients hospitalized with heart failure exacerbation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2015;8:77–86. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.001227

2. Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. Standards for the clinical structure and content of patient records. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2013. Available from: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/sites/default/files/media/Documents/standards-for-the-clinical-structure-and-content-of-patient-records.pdf?token=85IJ287y [accessed 10 July 2016].

3. Mann R, Williams J. Standards in medical record keeping. Clin Med 2003;3:329–32. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.3-4-329

4. Krumholz HM, Merrill AR, Schone EM et al. Patterns of hospital performance in acute myocardial infarction and heart failure 30-day mortality and readmission. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2009;2:407–13. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.883256

5. Al-Damluji MS, Dzara K, Hodshon B et al. Association of discharge summary quality with readmission risk for patients hospitalized with heart failure exacerbation: data report. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2015;8:109–11. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.001476