A study of 500 patients was conducted to ascertain how syncope is managed at the Ipswich Hospital NHS Trust. This was based on the variation in approach across the country despite the guidance from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the Heart Rhythm Society. Similar studies in the UK have indicated a number of inconsistencies in both the management and diagnosis of patients with suspected syncope.

We discuss the role of a syncope pathway, the need for a separate syncope clinic and for syncope experts.

Introduction

The aim of this study was to introduce a syncope pathway to the Ipswich Hospital NHS Trust (IHT), a busy district general hospital (DGH) and to emphasise the need for a syncope unit. We analysed the care of 500 patients treated for a syncopal event, our hypothesis being that the management of syncope within the trust was not up to the standards laid out in current guidelines. We also hypothesised that small changes, as well as larger scale organisational ones, would be hugely beneficial to patient care. If management was in line with guidelines, then we endeavoured to introduce a ‘Syncope Unit’ based on the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) position paper published in 2015.1 If management was not up to standards defined by European, American and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines, our aim was to improve training and interdepartmental communication regarding the management of syncope.

A thorough understanding of the management of syncope among specialists allows for a reduction in multi-speciality referrals, unnecessary tests and exhaustion of resources. The authors hope that this document provides a helpful review of syncope and its management. We provide references for further reading for those interested in the subject, and hope that cardiologists, neurologists and geriatricians, as well as specialist nurses in arrhythmia and heart failure find this paper useful.

IHT is a large, 800-bed DGH, and there were 62,791 admissions during the previous financial year. Of those, 1,884 cases were coded as transient loss of consciousness (TLOC). Using a syncope care pathway increases the diagnostic yield, reduces cost via reduced admissions, decreases the duration of hospital stay and reduces the number of unnecessary tests.2

Method

Using patient hospital numbers and the online hospital notes system, the records of all patients whose admission was coded as “Syncope”, “Collapse”, “TLOC” or “Blackout”, for the period January to July 2016, were collated. The notes of 500 patients were then evaluated. Those in whom it was clearly documented that they did not have loss of consciousness, or had prolonged loss of consciousness, such as status epilepticus, were not further considered. Those who had indeed had a TLOC had their notes examined in several domains. A background literature search was performed and particular attention was paid to the recommendations from the EHRA and NICE guidelines3,4 when designing the audit tool to measure if the investigation and treatment of syncope within IHT is at the recommended standard. A total of 113 patients had a TLOC. Their notes over the last three years were reviewed for any evidence of other admissions relating to syncope. Following this, data were collected in domains regarding:

- Previous cardiac history

- Symptoms preceding loss of consciousness

- Injuries sustained

- Investigations conducted

- Onward referral

- Diagnosis

- Treatment

Demographics

There is a varied population within the catchment area of IHT. Central Ipswich has a lower mean age than the surrounding rural Suffolk, which contains areas popular with retirees. Suffolk contains some wealthy areas, as well as some deprived areas in Ipswich and the coastal region. Ipswich has a strong multi-cultural element to its population, with large numbers of South East Asian, Middle Eastern and Eastern European residents.

Results

Each patient attending Accident and Emergency (A&E) with TLOC stayed on average 2.43 days. Patients with confirmed TLOC had, over the previous three years, 1.46 additional admissions with syncope.

Previous cardiac history

A history of ischaemic heart disease was present in 10% of patients, 14% had cardiac implantable devices, 20% significant valvular disease, 9% a family history of sudden cardiac death and 10% had known heart failure.

Symptoms

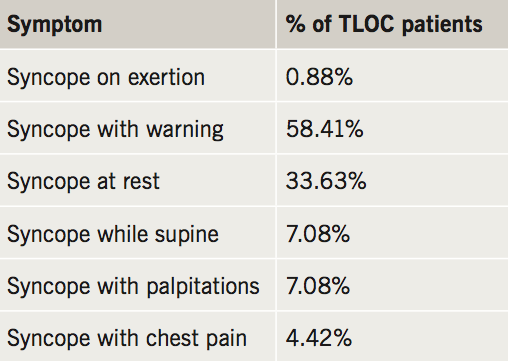

Associated symptoms are provided in table 1. There have been inconsistencies in defining ‘exertion’. One actual case of exertional syncope while playing football will be discussed later.

Injuries

Minor injuries (bruising or cuts that did not require suturing or admission) were sustained by 29.20% of patients. Three patients sustained major injuries, classified as fractures, bleeds or cuts requiring suturing.

Investigations

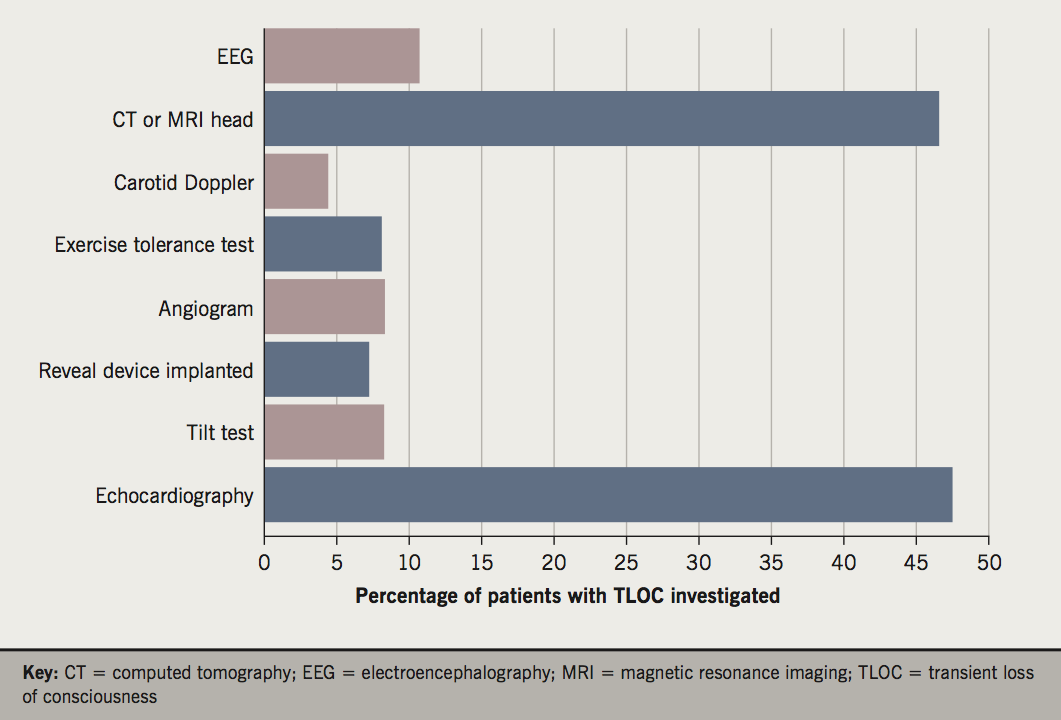

An abnormal electrocardiogram (ECG) was present on admission in 35.40%. Sinus bradycardia and atrial fibrillation (10 patients each) were the most common abnormalities. Four patients had ischaemic changes and J-waves were seen in the patient with true exertional syncope. Basic blood tests (full blood count [FBC], urea and electrolytes (U&Es) and blood glucose) were performed in 97% of patients: 12% had a D-Dimer and 54% had a troponin measured. There were 40% placed on telemetry, while only 13% had a lying and standing blood pressure recorded (of which 87% had a postural drop). Further investigations are provided in figure 1.

Referrals

Referrals (inpatient and outpatient) were often made to more than one speciality at the same time: 49% were referred to cardiology, 20% to neurology, 15% to falls clinic, 17% to another clinic and 23% had no clinic follow-up at all.

Diagnosis

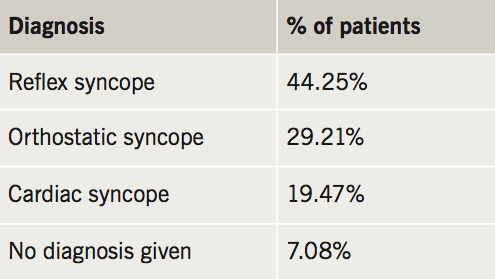

The diagnoses received are detailed in table 2.

Treatment

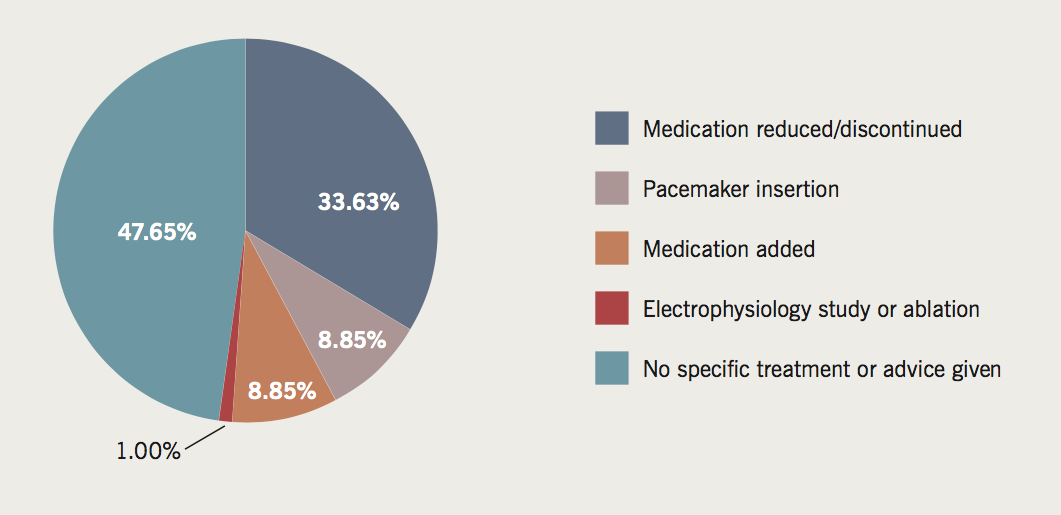

The treatment received is provided in figure 2.

Discussion

Our results show that concerning symptoms (syncope while supine or at rest) are experienced much more rarely than the more conventional syncope with warning. That said, there are still patients experiencing syncope that needs investigating thoroughly. On the other hand, there are also some patients who are not experiencing concerning symptoms who are being over-investigated.

J-waves were seen in a young man who had collapsed while playing football. He was an extremely physically fit athlete with a family history of sudden cardiac death on exertion. At a specialist clinic an ECG, echocardiogram and tilt-table testing were normal. He had a normal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan and he was eventually discharged with instructions to avoid high-intensity physical activity.

A striking figure is that of lying and standing blood pressure being performed in only 13% of patients. Given that of those 13%, most had a postural drop, this simple test is being under-valued. The recommended measure of lying and standing blood pressure is over three minutes.4

There is no mention in either the NICE or European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidance on the use of troponin as a baseline investigation for syncope.3-5 The ESC recommends it (along with brain natriuretic peptide [BNP] and D-Dimer) solely as a test to be performed in a specialist unit if considered to be indicated. Only 4.42% of our patients reported chest pain alongside a syncopal episode. Four patients had ischaemic changes on their ECG. However, 54% of patients had at least one troponin measurement. With only 19.47% of patients being diagnosed with any kind of cardiac syncope this is a low diagnostic yield. The cost of these tests is not unsubstantial at £1.90 per measurement.6

Almost half of patients who experienced a TLOC were referred to cardiology, and 15% of patients were referred to the IHT falls clinic. Many patients investigated for syncope certainly met criteria for frequent falls and further evaluation. A dedicated syncope clinic could be a more suitable environment for further investigation of these patients.1,2,7

It is significant that almost one-fifth of patients admitted with TLOC were deemed to have a cardiac cause. These higher-risk patients are those who need thorough investigation and are the most likely to benefit from a specialised syncope clinic or unit.8

Overview and background

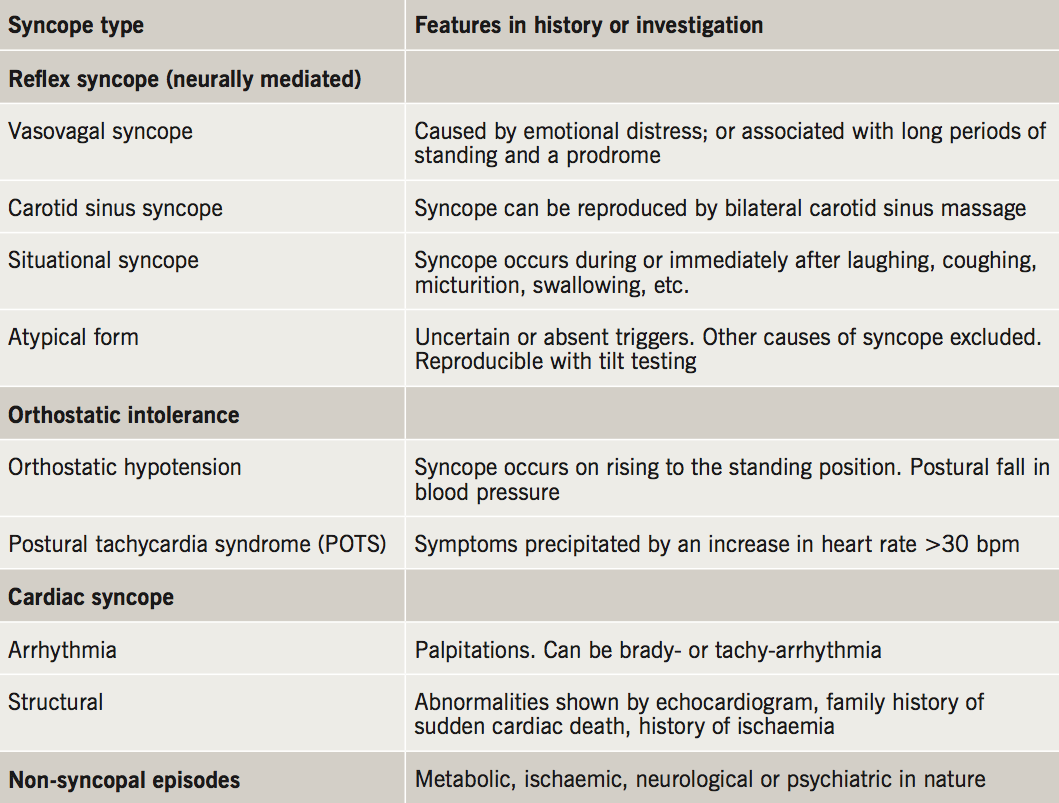

Syncope is defined as a TLOC with or without a prodrome of light-headedness or visual changes,2 and can be caused by a number of different factors (table 3).

Cardiac Holter monitoring, echocardiogram and tilt-table testing form the mainstay of investigation. However, they have been demonstrated to be unable to illicit a diagnosis in 25% of patients.9,10 A multiplicity of expensive and low-yield investigations does not lead to a definitive diagnosis.11 Diagnostic uncertainty results in delayed treatment and numerous outpatient appointments. This has potential for increased risk of adverse outcomes and great expense to the National Health Service (NHS).

Reflex syncope is the most common cause of syncope, which is associated with the lowest mortality.12 The precise mechanism of vasovagal syncope is poorly understood. Carotid sinus syndrome is brought about via an arterial baro-reflex that is over-sensitive to fluctuations in blood pressure (BP) level. Diagnosis is possible via carotid massage while attached to a cardiac monitor. Patients presenting with an asystolic response have been shown to benefit from the insertion of a permanent pacemaker.13

Cardiac syncope is associated with significantly higher one-year mortality.9 If an arrhythmia is the suspected cause, patients should be investigated further with Holter monitoring, or insertion of a loop recorder. Patients suspected of having any form of cardiac syncope should be referred to the cardiology team.4

Orthostatic syncope is another common, low-mortality cause of syncope. NICE guidelines define orthostatic hypotension as a drop in systolic BP of 20 mmHg or diastolic BP of 10 mmHg after standing for three minutes.5 A significant fall in BP that occurs immediately after standing, but resolves within three minutes, is not normally of any clinical concern. Patients with syncope and a postural drop should be referred for further investigation, such as tilt-table testing. Cardiac and vasodilator medication can cause orthostatic hypotension and should be reviewed.

Cardiac monitoring is not intended to be used as a general screening tool and, currently, the guidance is to only use in the presence of ECG abnormalities, heart disease or if exertional or supine syncope is suspected.9 The duration of monitoring is usually too short in patients with syncope. A new generation of external cardiac monitors that last two weeks and are able to communicate via the internet are becoming available and offer a less expensive solution, in some patients, to use of an implantable ECG loop recorder.

Implantable loop recorders have become widely available in cases where an arrhythmia is suspected. They have been shown to reduce the number of A&E attendances in patients with recurrent syncope.14

Correct use and interpretation of 12-lead ECG and lying and standing BPs alongside excellent history-taking is paramount, and often our most useful investigations. Cerebral imaging and electroencephalography (EEG) have a role to play from a neurological viewpoint if the history is suggestive.

Recommendations

- Obtaining detailed clinical history (including detailed collateral history), performing focused clinical examination.

- Appropriate use of tests.

- Regular education for new doctors and healthcare professionals.

- Providing accessible, clear pathway for the investigation and management of syncope.

- Use of the ‘Syncope Pathway’, which would in turn be triaged by a ‘Syncope expert’.

- Recommending multi-disciplinary ‘Syncope Clinic’ or setting up a ‘Syncope Unit’ next to the emergency department.

- To be aware of the useful guidelines surrounding syncope.

Our hypothesis was that syncope was not managed in line with current guidelines, and we have proven that there is certainly a disparity between what is recommended and what occurs in this DGH. If management was up to standards then our aim had been to introduce a clear pathway for emergency departments and general practitioner referrals, which would lead to patients being more appropriately investigated, managed and referred. However, given the large scope for improvement, we started with some simple measures. A presentation to the emergency department was given as well as a Grand Round to raise awareness of the importance of excellent history-taking, focused examination and investigation, and appropriate referral. We stress that education is the key. It is often the simplest points that can make the greatest difference. For instance, among 500 patients coded as ‘syncope’, only 113 had actually lost consciousness. One wonders how many of the 387 who did not lose consciousness were investigated and how long they stayed in hospital. Investigations are useful for honing in on causes of syncope, but the greatest tool in the physician’s bag remains accurate history-taking.

Some units have started training and appointing ‘syncope experts’. It was a consensus statement of the EHRA that specialist knowledge is needed to diagnose and investigate syncope. These experts could risk-stratify and triage patients, thus, ensuring appropriate use of investigations and an accurate diagnosis.4 Working with a slick and clear syncope pathway this would be an excellent framework for managing syncope.

Guidance from the EHRA published in June 2015, recommended that patients may benefit from specialised syncope units.4 The data here are insufficient to state categorically that a specialist syncope unit in Ipswich is necessary. However, there is certainly plenty of scope for improvement. A syncope clinic could become part of the existing falls or cardiology clinics, which are already providing service.

The authors of this paper hope that it has provided a reminder of the many guidelines surrounding syncope and also refreshed some of the basic knowledge, which is so fundamental to managing this condition.

Key messages

- Education and training surrounding the definition of syncope, history-taking and the appropriate use of investigations and interpretation

- Importance of inter-speciality liaison

- The benefit of Syncope Units and Joint Clinics

Funding

DD funded by Health Education East of England.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Professor Richard Sutton, Emeritus Professor in Clinical Cardiology, for his encouragement, guidance and valuable revision of the document.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

1. Kenny RA, Brignole M, Dan GA et al. Syncope unit: rationale and requirement – the European Heart Rhythm Association position statement endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society. Europace 2015;17:1325–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euv115

2. Brignole M, Disertori M, Menozzi C et al. Management of syncope referred urgently to general hospitals with and without syncope units. Europace 2003;5:293–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1099-5129(03)00047-3

3. The European Society of Cardiology Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope reviewed by Angel Moya, MD, FESC, Chair of the Guideline Taskforce with J. Taylor, MPhil. Eur Heart J 2009;30:2539–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehp393

4. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Transient loss of consciousness (‘blackouts’) in over 16s. CG109. London: NICE, 2014. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg109

5. Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines, and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2017;136:e60–e122. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000499

6. Courtesy of Kenneth Campbell, South Laboratory, Victoria Hospital KY2 5AH.

7. Parry SW, Frearson R, Steen N, Newton JL, Tryambake P, Kenny RA. Evidence-based algorithms and the management of falls and syncope presenting to acute medical services. Clin Med (Lond) 2008;8:157–62. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.8-2-157

8. Reed MJ, Newby DE, Coull AJ, Jacques KG, Prescott RJ, Gray AJ. The risk stratification of syncope in the emergency department (ROSE) pilot study: a comparison of existing syncope guidelines. Emerg Med J 2007;24:270–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.2006.042739

9. Kapoor WN. Evaluation and outcome of patients with syncope. Medicine (Baltimore) 1990;69:160–75. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005792-199005000-00004

10. Sarasin FP, Louis-Simonet M, Carballo D et al. Prospective evaluation of patients with syncope: a population-based study. Am J Med 2001;111:177–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00797-5

11. Brignole M, Ungar A, Bartoletti A et al. Standardized-care pathway vs. usual management of syncope patients presenting as emergencies at general hospitals. Europace 2006;8:644–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eul071

12. Arthur W, Kaye GC. The pathophysiology of common causes of syncope. Postgrad Med J 2000;76:750–3. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.76.902.750

13. Brignole M, Menozzi C, Lolli G, Bottoni N, Gaggioli G. Long-term outcome of paced and nonpaced patients with severe carotid sinus syndrome. Am J Cardiol 1992;69:1039–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9149(92)90860-2

14. Farwell DJ, Freemantle N, Sulke AN. Use of implantable loop recorders in the diagnosis and management of syncope. Eur Heart J 2004;25:1257–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehj.2004.03.010