On 23 June 2016, the UK public took to the polls and voted to leave the European Union (EU). Since that vote, everyone – from the farming community to the financial sector – has been trying to digest the result and understand what it might mean for them. The science community has been no exception, and with good reason. Scientific research is widely acknowledged as an international endeavour and, until now, EU membership has played a role in this. Science is also a real UK strength – UK institutions, when compared internationally, are ranked second in the world for the quality of their research,1 and the UK has one of the largest drug development pipelines globally – making it all the more important that we secure a positive future for UK science post-Brexit.

When it comes to cardiovascular disease (CVD), UK research has had (and continues to have) an enormous impact across the world – from influencing global care guidelines on hypertension to ensuring the right people are using statins to prevent a heart attack or stroke. These advances are helping people to live longer, healthier lives. Since the British Heart Foundation (BHF) was founded in 1961, UK death rates from CVD have fallen by more than half, and seven out of 10 people now survive a heart attack.

Secrets of success

So what have been the ingredients for this success, and how can we retain and build on these to ensure that the future holds the same promise of innovative treatments and breakthroughs in care?

First and foremost, we need talented people. Walk into any lab across the UK and you’ll find researchers of all nationalities working alongside each other. Almost a fifth of BHF-funded research leads are non-UK EU nationals and these researchers make a huge contribution to our understanding, diagnosis and treatment of CVD. The UK must remain open and welcoming to all those involved in research if we are to continue to successfully compete for talent from across the globe. In practice, this requires an immigration system that is transparent, proportionate and flexible enough to meet the UK’s changing skill needs and research priorities.

However, we will only attract the very best researchers if they are confident they’ll have access to adequate funding to conduct their research. Awards from the EU’s Framework Programmes (currently Horizon 2020) are an important part of the funding mix in the UK. UK-based researchers are very successful at securing this funding – between 2007 and 2013 the UK received €8.8 billion in EU research funding, having contributed €5.4 billion over the same period.2 It is not only the financial contribution that makes this source of funding important, but the type of grants available, many of which are designed specifically to promote collaboration. Government has set out its intention to explore future involvement with these types of funding programmes, but we’ll have to wait for further negotiations to determine exactly what this will look like in practice.

International collaboration

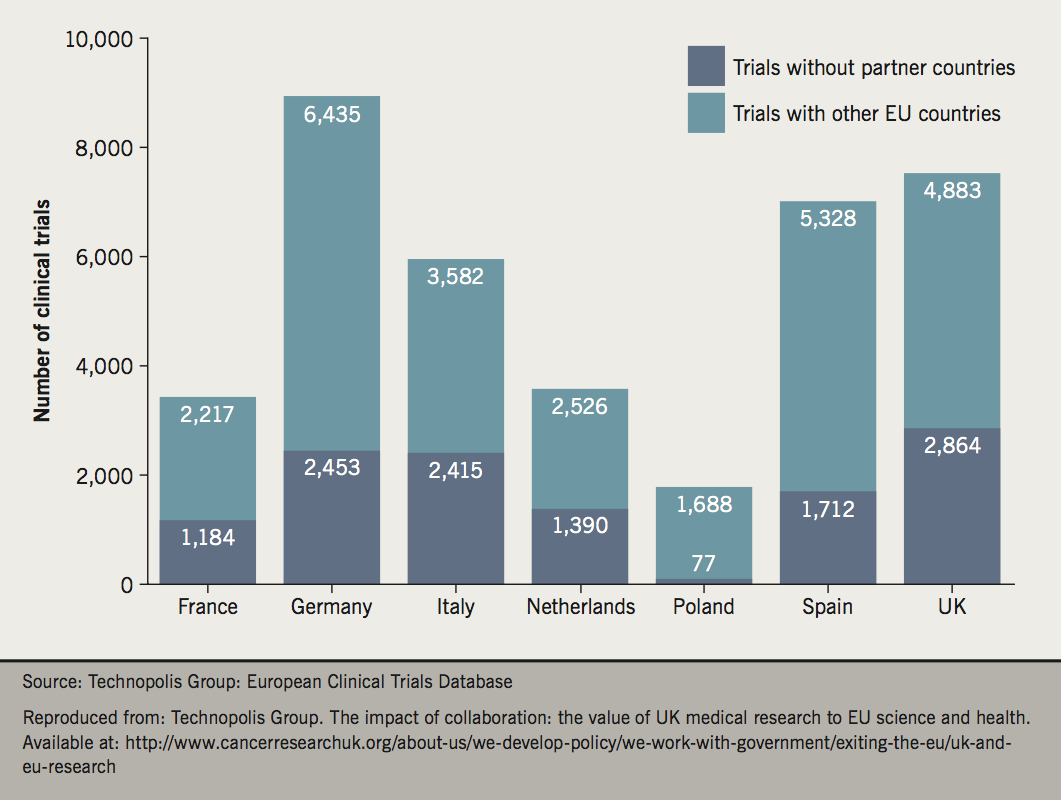

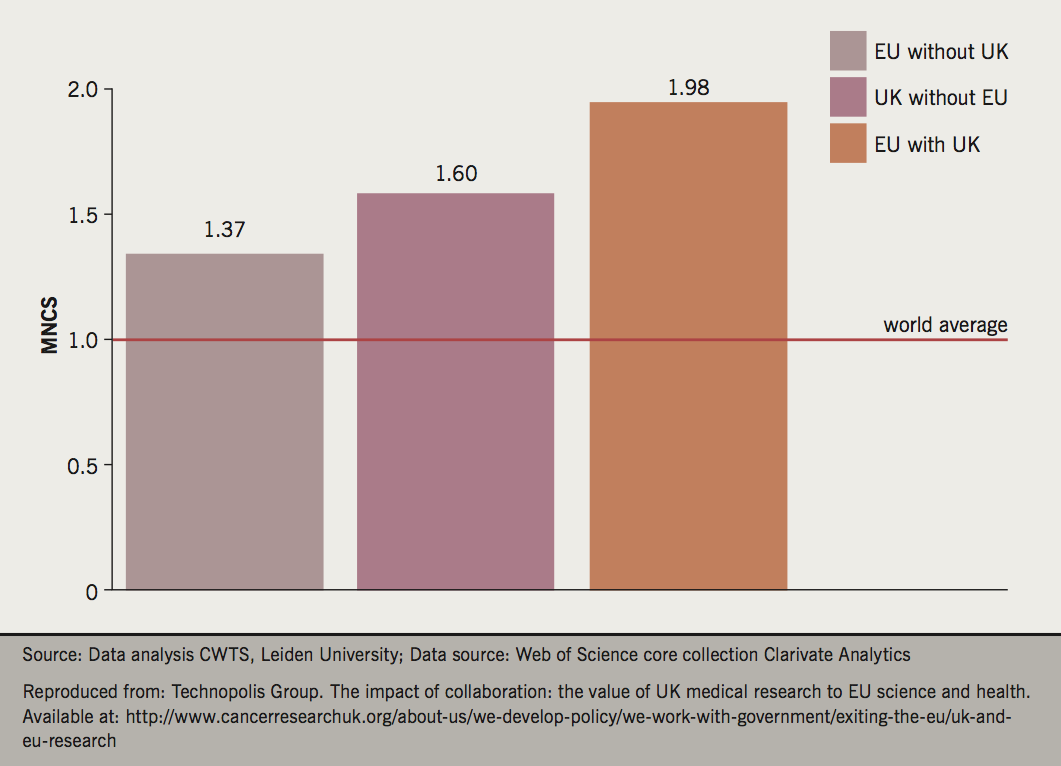

Clearly, successful science isn’t just about securing all the best resources and then walking away. Ongoing international collaboration and two-way dialogue play a vital role. In science, international collaboration is becoming increasingly common. Almost half of research publications that received BHF funding between 2010 and 2014 had an international co-author,3 and between 2004 and 2016, the UK collaborated with other EU countries on almost 5,000 clinical trials (figure 1).4 There is evidence to suggest that international collaboration improves the quality of our research. Medical research publications that report collaboration between the UK and the EU have a much higher citation impact than those produced in isolation (figure 2).4 This also holds true for cardiovascular research publications alone. The need for international collaboration also extends to areas such as medicines regulation, where the UK currently benefits from centralised processes and close working with its EU counterparts. A post-Brexit environment must continue to foster all these types of collaboration.

Since the referendum, we’ve heard some encouraging statements from the government about its vision for UK science. Early on, science and innovation was identified as one of the government’s 12 negotiating priorities for Brexit and, since then, we have seen a number of commitments for increased national investment in science and innovation, and statements recognising the value of international research collaboration. There is still a lot of detail missing as to exactly how the government will deliver on its vision for UK science post-Brexit, although we have recently seen some helpful progress in the form of a transition agreement, which is expected to last until the end of 2020. We now know that EU nationals already living in the UK and those arriving during the transition period will have the same rights as they do now,5 and that UK researchers will continue to be eligible to apply for Horizon 2020 funding during this time.6 Access to funding and the rights of EU citizens were particular concerns for many BHF-funded researchers and so these announcements provide some welcome short-term certainty. When it comes to UK science beyond the transition period, however, significant questions remain. As negotiations progress, we must ensure that researchers are provided with a clearer long-term picture of the future of UK science that gives sufficient reassurance that the UK will remain an attractive place to work and live.

For all the progress we’ve made, cardiovascular disease still causes more than a quarter of all deaths in the UK, killing one person every three minutes. Research is helping us to bring these numbers down but we’ve still got some way to go. People, funding, collaboration and stability all help scientific research to flourish – as the UK and the EU continue to forge their future relationship, we must ensure these vital elements are maintained.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

1. World Economic Forum. Global Competitiveness Report 2016–2017. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-competitiveness-report-2016-2017-1

2. Royal Society. UK research and the European Union: The role of the EU in funding UK research. 2016. Available at: https://royalsociety.org/topics-policy/projects/uk-research-and-european-union/

3. British Heart Foundation. Research Evaluation Report. Available at: https://www.bhf.org.uk/research/information-for-researchers/managing-your-grant/research-evaluation

4. Technopolis Group. The impact of collaboration: the value of UK medical research to EU science and health. Available at: http://www.technopolis-group.com/report/impact-collaboration-value-uk-medical-research-eu-science-health/ and http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-us/we-develop-policy/we-work-with-government/exiting-the-eu/uk-and-eu-research

5. Department for Exiting the European Union. Draft agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community. London: Department for Exiting the European Union, 19 March 2018. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/draft-withdrawal-agreement-19-march-2018

6. Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. UK participation in Horizon 2020: UK government overview with Q&A. London: Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, 5 March 2018. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-participation-in-horizon-2020-uk-government-overview