Peri-partum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) is one of the leading causes of maternal mortality worldwide, but the exact cause of PPCM is still unknown. PPCM is often associated with many risk factors, especially hypertension in pregnancy. This study aimed to evaluate the most influential risk factors of PPCM in Javanese ethnic patients.

The study was a case-control study involving 96 PPCM patients and 96 healthy non-PPCM parturients (control group) in the Hasan Sadikin Central General Hospital, West Java, Indonesia in the period from 2011 to 2014. A multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the most influential risk factors for PPCM.

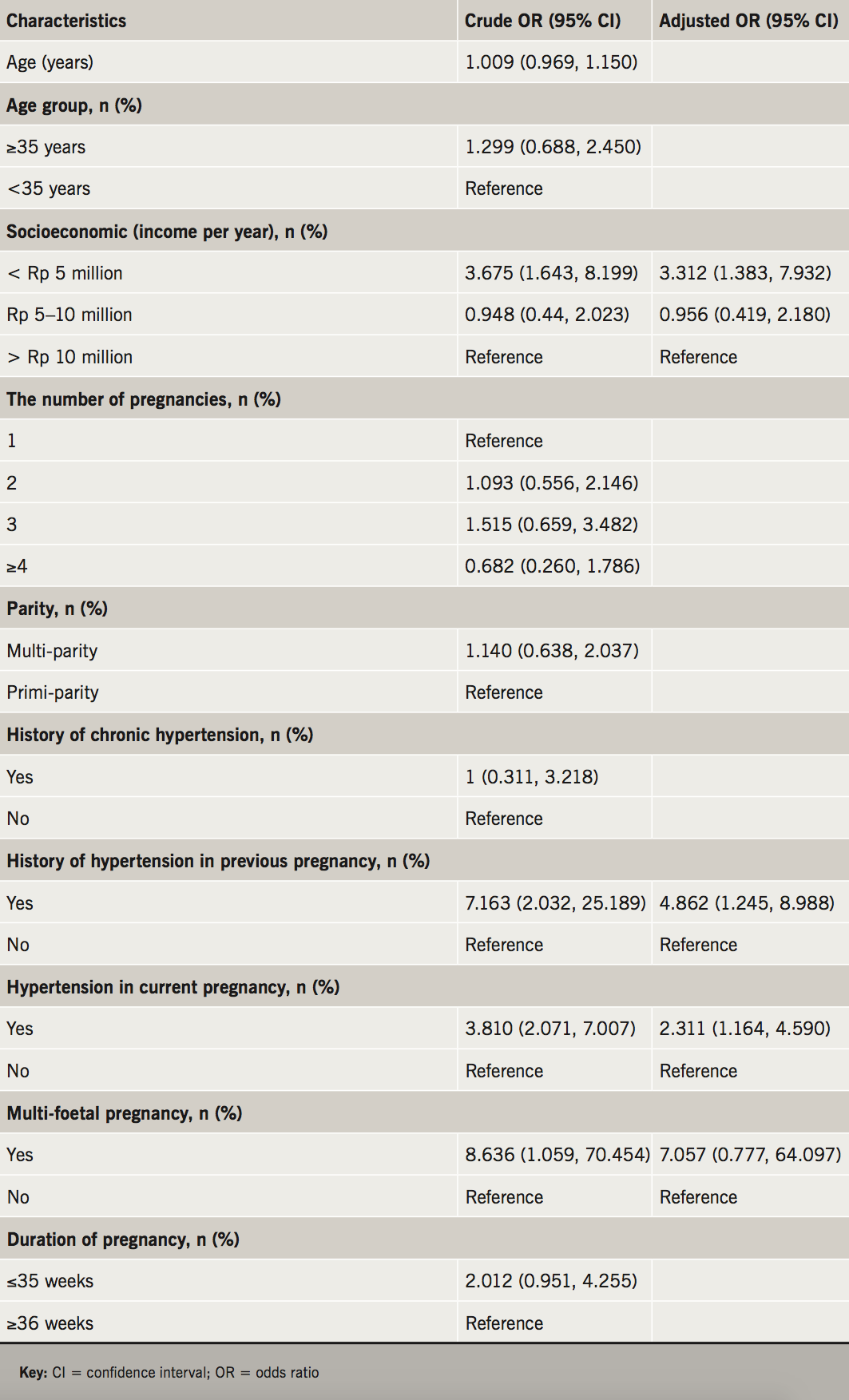

There were four significant and independent risk factors in this study, which were low socioeconomic status (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 3.312; confidence interval [CI] 1.383, 7.932), history of hypertension in previous pregnancy (adjusted OR 4.862; CI 1.245, 8.988), hypertension in current pregnancy (adjusted OR 2.311; CI 1.164, 4.590), and multi-foetal pregnancy (adjusted OR 7.057; CI 0.777, 64.097). Multiple logistic regression analysis showed the history of hypertension in previous pregnancy or hypertension in current pregnancy were the most influential independent risk factors of PPCM based on the narrowest confidence interval range, and after adjustment for other significant risk factors.

In this study, history of hypertension in previous pregnancy and hypertension in current pregnancy were the most influential and independent risk factors for PPCM. This study may increase awareness of treatment required for patients with hypertension in pregnancy, and also supports the pathogenesis of hypertension in pregnancy associated with PPCM, especially pre-eclampsia.

Introduction

Peri-partum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) is an idiopathic cardiomyopathy with symptoms and signs of heart failure, secondary to disorders of ventricular systolic function, in late pregnancy or postpartum, where no other cause of heart failure is found. PPCM is one of the main causes of maternal death worldwide. Data in the US show the incidence of PPCM reaches one in 2,500 to 4,000 pregnancies, while data on the incidence in Indonesia are still unknown. Data from the 2012 IDHS (Indonesian Demographic and Health Survey) showed heart failure, including PPCM, as the cause of a high maternal mortality rate in Indonesia reaching 228 per 100,000 live births. PPCM is different from other forms of dilated cardiomyopathy. Some studies show 40–43% of patients with PPCM may have reversibility of left ventricular function within six months after delivery, if it is detected as early as possible and they get immediate treatment.1-3

The cause of PPCM is currently unknown. However, it is often associated with various risk factors, such as multi-parities, maternal age ≥30 years, multi-foetal pregnancy, pre-eclampsia, and certain races, such as the African race.

Diversity in the most influential risk factor of PPCM in a particular country might be related to different race domination. Some studies show higher rates of PPCM with hypertension in pregnancy, especially pre-eclampsia in those of African race, but most data were obtained in PPCM patients with Caucasian race dominance. However, there is a lack of studies showing the most influential risk factor of PPCM in Asia, especially Southeast Asia.

This study involved only Javanese ethnic patients. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to determine the most influential risk factors of PPCM in this ethnic group.4-6

Methods

The research method is a case-control study involving 96 patients with PPCM as the case group, and 96 healthy non-PPCM parturients as the control group with a 1:1 ratio. This research was conducted at the Hasan Sadikin Hospital, Bandung, the main referral hospital in West Java, Indonesia, from 1 January 2011 until 31 December 2014. The case group was defined as newly diagnosed PPCM from 1 September 2013 until 31 December 2014, and also retrospective PPCM patients from medical records on 1 January 2011 until 31 December 2013 with complete data, and we are undoubtedly sure there was no difference in diagnostic procedure or treatment in patients recruited within study range. The control group was defined as clinically normal parturient between last trimester of pregnancy until five months after delivery with no sign and symptoms related to PPCM between 1 January 2014 and 31 December 2014.

Statistical analysis was performed with multiple logistic regressions, and the statistical results were obtained as crude odds ratios and adjusted odds ratios.

Results

The study shows significant differences in the baseline characteristics of case and control groups. Most of the patients with PPCM in the case group have a lower socioeconomic status (p<0.001) and more often have a history of hypertension in previous and current pregnancies (p<0.001), and multi-foetal pregnancy (p=0.035). The baseline characteristics are shown in table 1.

Overall, data from the baseline characteristics were evaluated utilising bivariate analysis, and then multi-variate analysis, to get the most influential risk factor of PPCM.

The results of this study based on bivariate analysis suggest low socioeconomic level was 3.67 times higher in patients with PPCM than the control group (confidence interval [CI] ranging from 1.643 to 8.199). The data on the number of pregnancies suggest multi-parity was 1.14 times higher in patients with PPCM than the control group. Based on bivariate analysis, history of hypertension in previous and current pregnancies was 7.153 (CI 2.032 to 25.189) and 3.810 (CI 2.071 to 7.007) higher in the PPCM group, respectively. The rate of multi-foetal pregnancy was 8.636 higher as compared with the control group (CI 1.059 to 70.454).

Those risk factors with significant differences between case group and control group were analysed using multi-variate analysis to detect the most influential risk factors of PPCM. Table 2 shows the statistical results.

The multi-variate analyses suggest lower socioeconomic status had 3.312 times (CI 1.383 to 7.932) increased risk of having PPCM after consideration of other significant factors. Hypertension in current pregnancy raises the risk of PPCM 2.311 times (CI 1.164 to 4.590); while the history of hypertension in previous pregnancy suggests 4.862 times (CI 1.245 to 8.988) increased risk of PPCM. Multi-foetal pregnancies increase the risk of PPCM 7.057 times (CI 0.777 to 64.097).

The results of this study, based on the multi-variate analysis and confidence interval at the narrowest range, and other significant risk factors under consideration, indicate that the most influential risk factors for PPCM in Javanese ethnic patients are the history of hypertension in previous pregnancy and hypertension in current pregnancies. Most of the case groups (57.9%) in this study had pre-eclampsia as the type of hypertension in pregnancy.

Discussion

PPCM is a cardiomyopathy with rare incidence and unknown cause; however, the risk factors having essential roles in the incidence of PPCM have been disclosed in several earlier studies. Those risk factors are multi-parity, maternal age >30 years, multi-foetal pregnancies, pre-eclampsia, and the individual races, such as the African race. There was diversity in the most influential risk factor of PPCM in a particular country, which might be related to different race domination. Some studies show higher rates of PPCM with hypertension in pregnancy, especially pre-eclampsia in African race, but various data were obtained in PPCM patients with Caucasian race dominance.1,4,7

Until now there was no previous study showing the most influential risk factor of PPCM in Southeast Asia, mainly Javanese ethnic patients.

This study showed that history of hypertension in previous pregnancy, and hypertension in current pregnancy is the most influential risk factor for PPCM.8 Earlier studies explained 41.2% of patients with PPCM in Japan have hypertension in pregnancy, with 42.8% being pre-eclampsia.7 Also, some other studies show the strong relationship between PPCM and hypertension in pregnancy. Data in the US showed 65% of patients with PPCM have hypertension in pregnancy, 13.9% of which have pre-eclampsia. Literature indicates nearly half of patients with PPCM had hypertension in pregnancy. A meta-analysis suggests the prevalence of pre-eclampsia and other forms of hypertension in pregnancies is significantly higher in PPCM patients than the general population. This suggests a strong relationship between hypertension in pregnancy and PPCM and, thus, supports some theories that point out the similarities of pathogenesis between hypertension in pregnancy, especially pre-eclampsia, with PPCM.1,9-12

The proposed mechanism describes the similarities of pathophysiologic mechanism between hypertension in pregnancy, especially pre-eclampsia, over the incidence of PPCM through anti-angiogenic factors produced by the placenta, which increase in late months of pregnancy, especially in patients with pre-eclampsia. The anti-angiogenic factors are a soluble version of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (sVEGFR-1), which binds to and neutralises vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). The effects of these factors would cause disorders of endothelial homeostasis, including glomerular blood vessels, leading to hypertension and proteinuria in pre-eclampsia. These anti-angiogenic factors also have cardiotoxic effects, especially toward the myocardium. Some women, who do not have enough resistance against the cardiotoxic effects of these factors, would develop cardiomyopathy. This also could explain the most common onset of PPCM in late gestation.13-18

The results of this study, and some earlier studies related to the strong relationship between PPCM and pre-eclampsia, may increase awareness of the risk of left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with pre-eclampsia, especially Javanese ethnic patients, who have signs and symptoms of heart failure.13,19 It is essential to note differences in the management of patients with hypertension in pregnancy with systolic dysfunction or diastolic dysfunction as a result of an increase in blood pressure; also, the prognoses of these two cases are different. Early detection of the onset of PPCM in patients with hypertension in pregnancy plays a role in the magnitude of potential reversibility of patients with PPCM. Further studies would be needed to ensure the overlapping mechanisms of pre-eclampsia and PPCM.13,19,20

The limitation of this study is that it does not differentiate hypertension in pregnancy into pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, gestational hypertension, or chronic hypertension that may have a different pathogenesis. Also, the number of subjects in this study is relatively small. This study was hospital-based with a single centre, instead of population-based, so it is not certain that similar results would be obtained if this study were conducted on certain population base. Further research should be multi-centre, with the matching of important confounders, such as maternal age, gestational age, and parity.

Conclusion

Hypertension in pregnancy has a strong relationship with PPCM. The results of the study show that hypertension in pregnancy and history of hypertension in previous pregnancy are major risk factors that have the most significant effect on the incidence of PPCM. Indeed, further studies are necessary to know the proper overlapping mechanisms of pre-eclampsia with PPCM. The results of the study are expected to increase awareness, leading to comprehensive treatment toward patients with hypertension in pregnancy, as well as being one of the pieces of evidence of any linkage between the pathogenesis of hypertension in pregnancy with the onset of PPCM.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Key messages

Peri-partum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) is one of the leading causes of high maternal mortality in Indonesia

The exact cause of PPCM is still unknown, and there is diversity in the most influential risk factor for PPCM between countries that might be related to different race domination

In this study with Javanese ethnic patients, we showed the history of hypertension in previous pregnancy and hypertension in current pregnancy were the most influential and independent risk factors for PPCM

References

1. Elkayam U. Clinical characteristics of peripartum cardiomyopathy in the United States: diagnosis, prognosis, and management. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:659–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.047

2. Chee KH, Azman W. Prevalence and outcome of peripartum cardiomyopathy in Malaysia. Int J Clin Pract 2009;63:722–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01449.x

3. Ministry of Health, Republic of Indonesia. Health profile of Indonesia. Available from: http://www.depkes.go.id

4. Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Sliwa K. Pathophysiology and epidemiology of peripartum cardiomyopathy. Nat Rev Cardiol 2014;11:364–70. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2014.37

5. Sliwa K, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Petrie MC et al. Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of peripartum cardiomyopathy: a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on peripartum cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J 2010;12:767–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjhf/hfq120

6. Shani H, Kuperstein R, Frenkel Y, Arad M, Sivan E, Simchen M. Peripartum cardiomyopathy risk factors and prognosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;199:149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2008.09.535

7. Kamiya CA, Kitakaze M, Ueda HI et al. Different characteristics of peripartum cardiomyopathy between patients complicated with and without hypertensive disorders. Circ J 2011;75:1975–81. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-10-1214

8. Cruz MO, Briller J, Hibbard JU. Update on peripartum cardiomyopathy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2010;37:283–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2010.02.003

9. Rana S, Powe CE, Salahuddin S et al. Angiogenic factors and the risk of adverse outcomes in women with suspected preeclampsia. Circulation 2012;125:911–19. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.054361

10. Bello N, Rendon IS, Arany Z. The relationship between preeclampsia and peripartum cardiomyopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:1715–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.08.717

11. Harper MA, Meyer RE, Berg CJ. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: population based birth prevalence and 7-year mortality. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:1013–19. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e31826e46a1

12. McNamara D, Elkayam U, Alharethi R et al. Peripartum cardiomyopathy in North America: results of the IPAC study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:905–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.1309

13. Fett D. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: a puzzle closer to solution. World J Cardiol 2014;6:87–99. https://doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v6.i3.87

14. Patten IS, Rana S, Shahul S et al. Cardiac angiogenic imbalance leads to peripartum cardiomyopathy. Nature 2012;485:333–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11040

15. Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J et al. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest 2006;111:649–58. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI17189

16. Melchiorre K, Thilaganathan B. Maternal cardiac function in preeclampsia. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2011;23:440–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/GCO.0b013e32834cb7a4

17. Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Kaminski K, Podewski E et al. A cathepsin D-cleaved 16 kDa form of prolactin mediates postpartum cardiomyopathy. Cell 2007;128:589–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.036

18. Powe CE, Levine RJ, Karumanchi SA. Preeclampsia, a disease of the maternal endothelium: the role of antiangiogenic factors and implications for later cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2011;123:2856–69. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.853127

19. Young BC, Levine RJ, Karumanchi SA. Pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Annu Rev Pathol 2010;5:173–92. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102149

20. Sibai B, Dekker G, Kupferminc M. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet 2005;365:785–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71003-5