Movement restrictions are given to patients after cardiac rhythm device implantation, despite little consensus, or evidence that they reduce complications. We conducted a UK survey assessing the nature of the advice and if it varies between individuals and institutions. A survey was distributed to cardiac rhythm teams at UK implanting centres. Questions concerned the advice that is given, its source, and who is responsible for providing it.

There were 100 responses from 42 centres. Advice is given by physiologists, nurses, and cardiologists. Advice comes from local protocols, information leaflets, current hospital opinion, manufacturers, national leaflets, published research and audit data. Within and between centres there was little agreement on what the advice should be. Depending on who gives the advice, a number of leisure pursuits were either completely unrestricted or restricted indefinitely. Cardiologists were less restrictive than others.

In conclusion, this is the first UK survey to assess the movement and mobilisation advice given to patients after device implantation. There is variation in the source and nature of advice. Over-restriction could impact on patients’ quality of life. Contradictory advice could cause uncertainty. Further work should determine the impact of this variation and how the effects could be safely mitigated.

Introduction

The number of patients receiving cardiac rhythm devices (CRDs) in the UK continues to grow.1 After device implantation, to reduce the probability of lead displacement and, therefore, re-intervention, patients are often advised to limit certain arm movements and physical activities for a defined period of time.2 Sources of this post-procedure movement and mobilisation advice include manufacturers’ guidelines, national information leaflets and local implanting centre policy. However, there is no consensus guidance on what the advice should be, and no published evidence to show that post-implant movement restrictions reduce complication rates. In addition, emerging data suggest that over-restriction may be harmful, and early mobilisation safer than previously thought.2-5 The aim of this survey was to determine the variation in post-implantation advice that is given to patients in CRD implanting centres in the UK.

Method

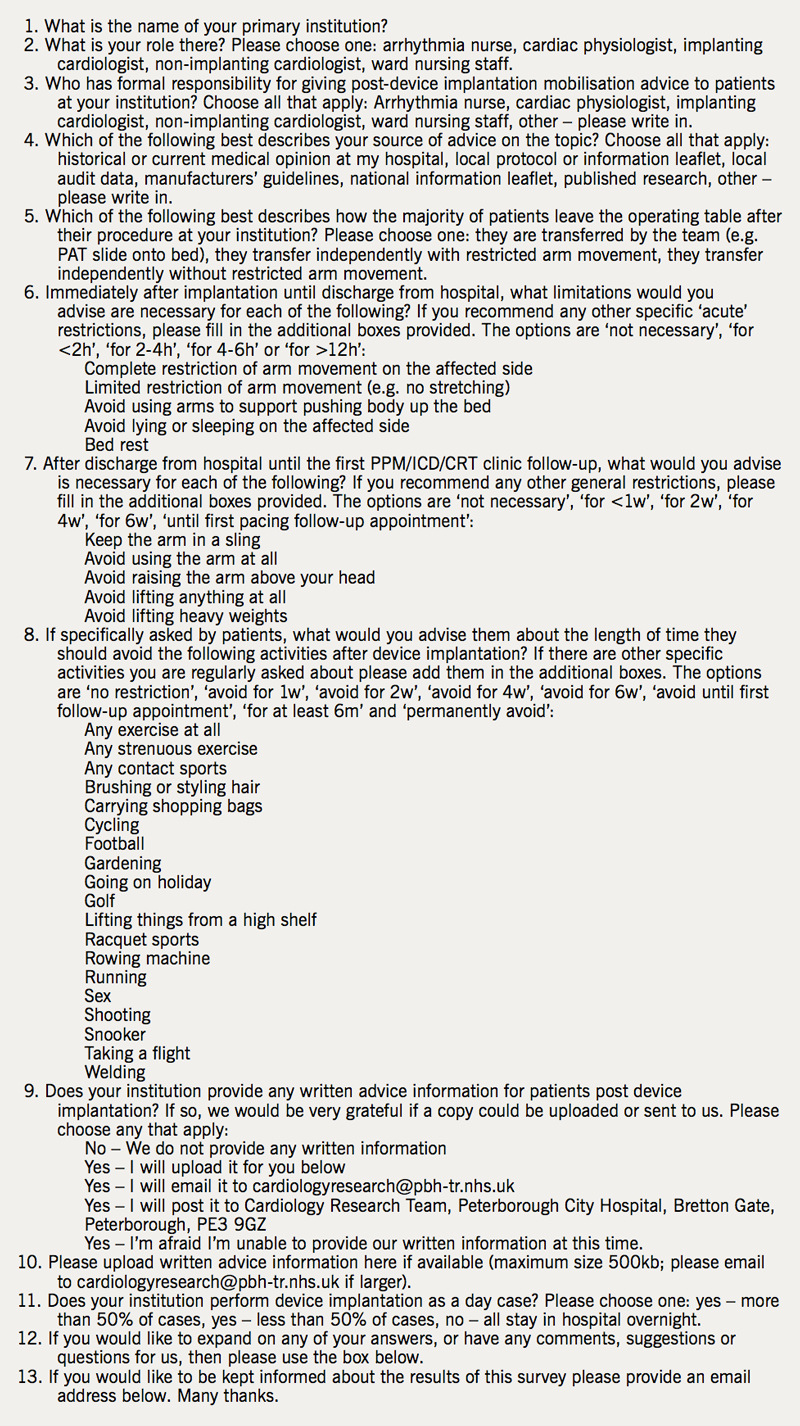

An online survey (see appendix) was designed and piloted within our local CRD team in Peterborough City Hospital. After feedback and modification, the final survey was approved by the British Heart Rhythm Society (BHRS). The survey asked 13 questions about who is responsible for providing movement and mobilisation advice, what the advice is, and where it is sourced from. Respondents were also asked to send in any local protocols or information leaflets that they had produced. The survey was posted online at the BHRS website and their members were encouraged to respond. Implanting centres were identified from the National Audit of Cardiac Rhythm Devices. Private and children’s hospitals were excluded. Lead cardiac physiologists at all UK National Health Service (NHS) adult implanting centres were contacted directly via both telephone and email to ask if they would distribute the survey within their implanting teams. Responses were encouraged from cardiologists, arrhythmia nurses, cardiac physiologists, and any other healthcare professionals who were involved in providing post-CRD implantation movement and mobilisation advice. Results were collected and analysed in Microsoft Excel. Some multiple-choice questions were in a ‘select all that apply’ format such that not all percentages add up to 100. We received no funding for the study and respondents were given no incentive to reply.

Results

Responses

There were 100 responses received from 42 of the 176 UK NHS adult implanting centres (response rate 24%). There was a wide distribution of responding centres with representation from all four regions of the UK (figure 1). Responses came from cardiac physiologists (45%), implanting cardiologists (33%), arrhythmia nurses (13%) and ward nurses (9%), respectively.

Provision of advice

Post-implant movement and mobilisation advice is given to patients by cardiac physiologists (87%), ward nurses (47%), arrhythmia nurses (43%), implanting cardiologists (40%) and non-implanting cardiologists (3%). It was stated by 65% of respondents that advice is provided by multiple healthcare professionals. Of the 18 institutions who returned two or more surveys, there was disagreement on exactly who was responsible for providing advice to patients in 16 of the 18 centres (89%).

Sources of advice

Advice is sought from local protocol or information leaflets (68%), historical or current hospital opinion (64%), manufacturers’ guidance (21%), a national information leaflet (21%), published research (19%) and local audit data (8%). In the centres who returned two or more surveys, none agreed on the preferred source of advice at their centre.

Nature of advice

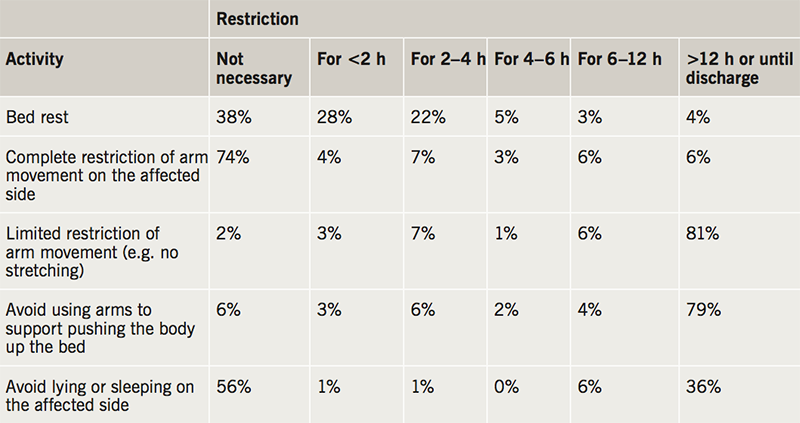

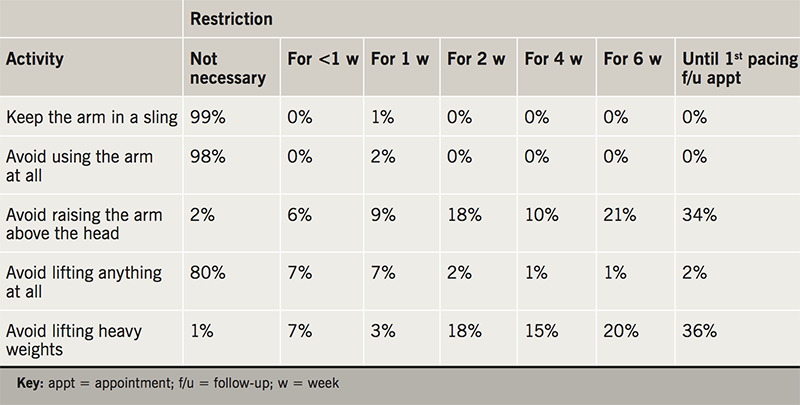

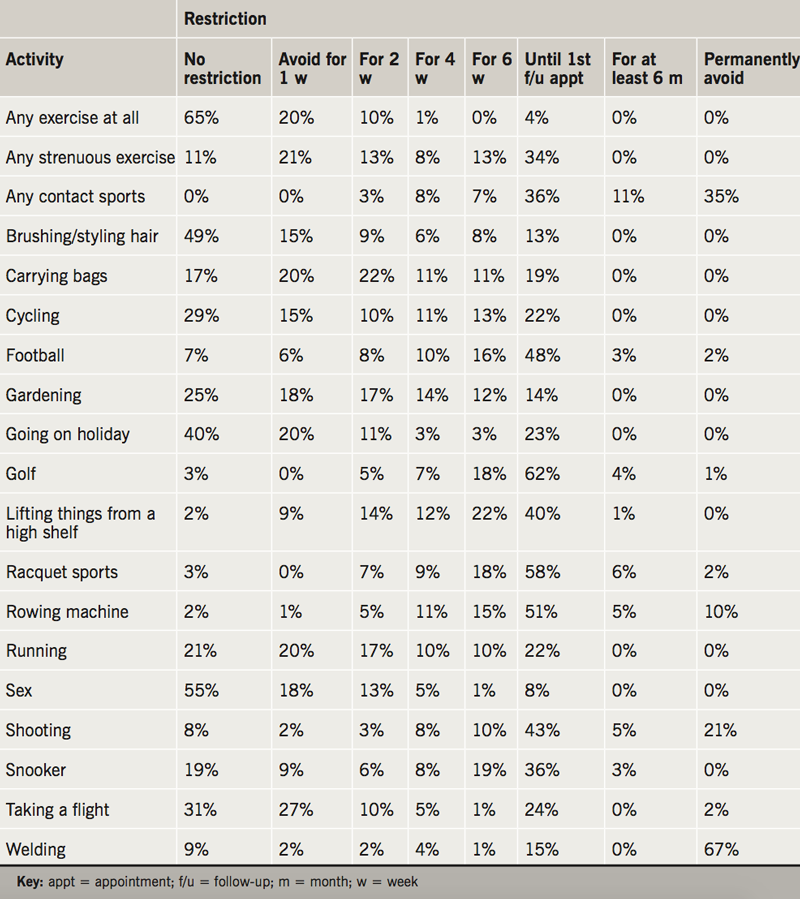

After device implantation, patients are advised to leave the operating table by team transfer (63%), independently but with restricted arm movement (34%), or without any help or restriction (1%). All patients were admitted overnight in 18% of centres, and the remainder of centres perform day cases (82%). The range of advice given to patients before discharge, after discharge, and for a number of leisure activities, are shown in tables 1, 2 and 3. There was marked variation in the time restrictions advised to patients after device implantation. For all 29 of the movements and leisure activities included in the survey there were no examples of complete agreement on the optimum length of time they should each be permitted or restricted for. For example, depending on the individual providing the advice, exercise, running, cycling, gardening, carrying shopping bags, brushing/styling hair, going on holiday and having sex may be completely unrestricted or restricted until the first six-week follow-up appointment. Welding, racquet sports, playing football, shooting, taking a flight and playing golf may be either completely unrestricted or restricted indefinitely.

Locally produced information leaflets were received from six centres. All contained movement and mobilisation advice, however, there was significant variation in the advice. For example, ‘raising the arm above the head’ was variably restricted for one, two, four or six weeks depending on the centre and leaflet in question. One local information leaflet advised “wearing a sling for 1–2 weeks to remind [patients] to avoid strenuous activity”. Implanting cardiologists were more likely to allow a number of activities at an earlier time than cardiac physiologists, arrhythmia nurses and ward nurses, including ‘lifting the arm above the head’, ‘lifting things from a high shelf’, ‘lifting heavy weights’, ‘carrying shopping bags’, ‘undertaking strenuous exercise’, ‘undertaking contact sports’, ‘using a rowing machine’, ‘shooting a gun’ and ‘playing snooker’.

Discussion

This is the first UK survey, and the most comprehensive to date, that assesses the nature and variation of movement and mobilisation advice that is given to patients after CRD implantation. The results demonstrate that the responsibility for providing post-implantation movement advice is shared between cardiac physiologists, ward nurses, arrhythmia nurses and implanting cardiologists. However, there is little consensus on which healthcare professional should provide the advice, and without published data or national guidelines there is wide variation in the advice that is given.

Depending on the implanting institution and individual providing the advice, some activities may be either completely unrestricted or restricted indefinitely. For example, some patients are advised to stop lifting their arm above their head forever, while others are free to do so from the day of implantation onwards. The same inconsistencies apply to other leisure pursuits and routine activities, such as playing sports or lifting shopping bags. If a patient’s occupation or hobby is adversely affected by these restrictions, there could be a major impact on their quality of life.

Not only did the nature and sources of advice differ between individuals and institutions, we also found little consensus within centres themselves. Of the 18 centres that returned two or more surveys, two agreed on who should provide the advice and none agreed on the source of that advice. Furthermore, implanting cardiologists appear to be less restrictive in their advice compared with other healthcare professionals. Once again, the potential impact on quality of life for patients could be substantial if they are given overly cautious advice without appropriate justification.

The rationale for prolonged immobilisation remains controversial. A balance must be struck between allowing the device leads time to adhere to vascular and myocardial endothelial surfaces and reducing the perceived risks of prolonged immobilisation, such as frozen shoulder, muscle atrophy and venous thrombosis.5 Historically, pacemakers were implanted in the upper abdominal wall under general anaesthetic. To avoid lead displacement, patients were advised strict bed rest for four to five days with arm movement restriction.6 More recently, the small number of case reports describing lead displacement secondary to ‘sagging heart syndrome’ or ‘twiddler’s syndrome’ provide only low level evidence to support arm movement restriction.7-9 Device technology has evolved significantly, but the data supporting post-implant movement and mobilisation restriction has not, and recent data suggest that lead displacement may be more correlated with the technique and experience of the operator than immobilisation of the arm.4,10

The evidence for movement restriction has been reviewed by Bavnbek et al. and is worth briefly discussing again here.4 Findikoglu and colleagues demonstrated that patients who underwent CRD implantation less than three months ago had more ipsilateral shoulder movement disability than those who underwent implantation over three months ago, and concluded that this shoulder debility “might be related to restriction of motion in the [ipsilateral] shoulder joint”.2 Miracapillo and colleagues then randomised 134 implant patients to either early (three hours) or late mobilisation (12 hours) and observed no significant difference in clinical outcome, complications or electrical lead parameters up to two months post-discharge.3 Naffe and colleagues subsequently consented 10 patients to perform a number of passive, active and resistive arm exercises, both above and below the head, immediately after CRD implantation. They also found no electrical evidence of lead displacement.5 Interestingly, the same authors then surveyed implanting cardiologists in 48 states of the USA, asking about the advice they give to patients after implantation. As in our UK study, they also found a wide variation in the advice that is provided. For example, some clinicians recommended free arm movement immediately post-implant, while others suggest that a sling is worn for four weeks.5

However, limiting the advice provided or expressing uncertainty may also be harmful. A survey of 93 patients in Pakistan showed that “a lack of information may result in unnecessary self-imposed restrictions that can be disabling”.11 Compare this with the results of the study by Naffe et al., where after being harmlessly guided through the various passive, active and resistive arm exercises patients were not only free of adverse complications, they also developed “complete confidence in the mobilisation protocol”. This juxtaposition suggests there may be a psychological, as well as physical, benefit to providing more specific advice to patients.5

Despite the lack of published data or expert consensus, national information leaflets have been published in both the USA and the UK.12-15 However, this advice is also confusing and contradictory. The BHRS standards for follow-up of pacemaker patients contains no movement and mobilisation advice at all.15 The Arrhythmia Alliance leaflet advises not raising the ipsilateral arm above the head for one week, the American College of Sports Medicine suggests two to three weeks, and the British Heart Foundation suggests six weeks.12-14 Similar disagreement was found among the locally produced information leaflets we received from responding centres in our survey, as well as in the various different guidance documents that are published by device manufacturers.15-18

Anxieties around lead displacements are pervasive among clinicians, as well as patients. This observational study adds to the growing body of literature that challenges current practice and demonstrates the need for further research work. To reduce the physical and psychological burden to patients of both over- and under-restriction, more research is needed to assess what advice is and is not appropriate. While complete consensus in a survey of this kind is not possible, the variation in opinion in our study is particularly wide, and it is reasonable for patients to expect at least similar advice from different healthcare professionals after CRD implantation. This survey also reveals the need for a national consensus document and randomised trials comparing restrictive and liberal post-implant movement and mobilisation advice protocols. If safe, fewer post-implant movement restrictions could streamline device pathways, encourage more day-case procedures, and reduce healthcare costs, care inequalities and patient anxieties.

There are many limitations to this study. First, its findings are similar to those of the 2009 US survey by Naffe et al., although ours is more up to date, more comprehensive, and the first such study in the UK and NHS.5 Second, despite distributing the survey via the BHRS website and contacting all adult NHS UK implanting centres directly via telephone and email, the response rate is low, particularly in Scotland. However, the National Audit of Cardiac Rhythm Device Management also has difficulty recruiting from Scotland, the overall response numbers are comparable with similar surveys in the USA and Europe, and, on balance, we feel that the breadth of responses spanning a number of institutions and healthcare professionals probably provides a relatively representative sample of opinion in this area.1,5,19 A postal survey or compulsory national audit, for example, may improve the response rate without the biases that incentives bring. Third, despite being equally responsible for providing advice, in comparison with implanting cardiologists, arrhythmia nurses are relatively under-represented in this survey. The reasons for this are unclear, however, it may be due to variation in BHRS membership rates. Fourth, in this survey, no distinction is made between devices for defibrillation, permanent pacing and cardiac resynchronisation. Given that their indications and patient cohorts are different, the risks and, therefore, recommended activity restrictions may vary too. Finally, no attempt was made to assess the extent to which patients adhere to the advice that is provided to them. Moving forward, the advice that is given should be optimised in parallel with measures that assess and improve patient compliance with any published movement and mobilisation advice.

Conclusion

This is the first survey to demonstrate variation in the sources and extent of movement and mobilisation advice that is given to patients after cardiac rhythm device implantation in the UK. Further work is needed to clarify the extent of this variation, its clinical impact, and how these effects could be safely mitigated against.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements

The team would like to thank all those who kindly gave up their time to complete the survey.

Study approval

This survey was approved by the British Heart Rhythm Society.

Disclaimer

The words expressed in the submitted article are our own and not an official position of our institutions.

Key messages

- Little is known about the nature of the movement and mobilisation advice given to UK patients after cardiac rhythm device implantation

- This survey demonstrates significant variation in the nature of movement and mobilisation restriction advice, where it is sourced from, and who is responsible for providing it

- Over-restriction could impact on patient’s quality of life and contradictory advice could cause uncertainty for patients

- To mitigate the effects of this variation, further work could generate a consensus document, assess and improve adherence to published protocols, and compare outcomes between liberal and restrictive approaches

References

1. National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (NICOR). National audit of cardiac rhythm management devices: April 2015 – March 2016. London: NICOR, 2017. Available from: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/nicor/audits/cardiacrhythm/documents/annual-reports/crm-devices-national-audit-report-2015-16 [accessed 21 August 2018].

2. Findikoglu G, Yildiz BS, Sanlialp M et al. Limitation of motion and shoulder disabilities in patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices. Int J Rehabil Res 2015;38:287–93. https://doi.org/10.1097/MRR.0000000000000122

3. Miracapillo G, Costoli A, Addonisio L et al. Early mobilization after pacemaker implantation. J Cardiovasc Med 2006;7:197–202. https://doi.org/10.2459/01.JCM.0000215273.70391.bf

4. Bavnbek K, Ahsan SY, Sanders J, Lee SF, Chow AW. Wound management and restrictive arm movement following cardiac device implantation – evidence for practice? Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2010;9:85–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2009.11.008

5. Naffe A, Iype M, Easo M et al. Appropriateness of sling immobilization to prevent lead displacement after pacemaker/implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2009;22:3–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2009.11928456

6. Bryant RB, Waddy JL. The pacemaker patient and his management. Aust Nurses J 1974;4:29–35.

7. Tokano T, Nakazato Y, Sasaki A et al. Dislodgment of an atrial screw-in pacing lead 10 years after implantation. PACE 2004;27:264–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.2004.00425.x

8. Iskos D, Lurie KG, Shultz JJ, Fabian WH, Benditt DG. “Sagging heart syndrome”: a cause of acute lead dislodgment in two patients. PACE 1999;22:371–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.1999.tb00453.x

9. Lal RB, Avery RD. Aggressive pacemaker twiddler’s syndrome. Dislodgement of an active fixation ventricular pacing electrode. Chest 1990;97:756–7. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.97.3.756

10. Vardas PE, Auricchio A, Blanc JJ et al. Guidelines for cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy. The Task Force for Cardiac Pacing and Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace 2007;9:959–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eum189

11. Aqeel M, Shafquat A, Salahuddin N. Pacemaker patients’ perception of unsafe activities: a survey. BMC Cardiovas Disord 2008;8:31. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-8-31

12. British Heart Foundation. Pacemaker. London: BHF, 2018. Available from: https://www.bhf.org.uk/publications/treatments-for-heart-conditions/pacemakers [accessed 21 August 2018].

13. Ehrman J. American College of Sports Medicine Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013;195.

14. Arrhythmia Alliance. Pacemaker patient information. Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire: Arrhythmia Alliance, 2017. Available from: http://www.heartrhythmalliance.org/resources/view/283/pdf [accessed 21 August 2018].

15. British Heart Rhythm Society. Standards for implantation and follow-up of cardiac rhythm device management devices in adults. London: BHRS, April 2017. Available from: http://bhrs.com/files/files/170529-sp-BHRS%20standards%20for%20CRM%20devices%202017.pdf [accessed 21 August 2018].

16. Medtronic. Common questions about your heart device. Available at: http://www.medtronic.com/us-en/patients/treatments-therapies/common-questions.html#how-active [accessed on 21 August 2018].

17. Boston Scientific. Recovering from your pacemaker procedure. Available at: http://www.bostonscientific.com/en-US/patients/about-your-device/pacemakers/after-your-procedure.html [accessed on 21 August 2018].

18. Abbott. Pacemakers. Available at: https://www.sjmglobal.com/en-int/patients/arrhythmias/our-solutions/pacemakers/ [accessed 21 August 2018].

19. Todd D, Bongiorni MG, Hernandez-Madrid A, Dagres N, Sciaraffia E, Blomström-Lundqvist C. Standards for device implantation and follow-up: personnel, equipment, and facilities: results of the European Heart Rhythm Association survey. Europace 2014:16:1236–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euu209