Advanced nursing roles supported by competency-based training have been pioneered over the last 25 years, with emphasis on the development of specific medical skills. This has largely been influenced by increasingly complex medical needs, costs of healthcare and the significant reduction in available doctors. With this reduction of doctors in training and departmental support for expanding nursing roles, we devised a local initiative to train an experienced nurse to perform diagnostic coronary angiography. Our aim was to provide a safe and enhanced service and improve procedural efficiency within the cardiac day unit.

A prospective audit of 250 coronary angiography procedures was performed in the training period between 24 September 2014 and 9 October 2015. Post-training, 143 procedures were performed between 12 October 2015 and 20 July 2016. The prospective audit was performed to explore the safety, effectiveness and quality of nurse-delivered diagnostic coronary angiography. An audit form was created to assess each component of the procedure. This included, gaining patient consent, success in gaining arterial access, success in intubating the left and right coronary arteries, observation of haemodynamics, observation of complications and reporting the findings. Financial impact, patient satisfaction and staff perception outcomes were also audited.

When directly compared with contemporaries, nurse-delivered diagnostic coronary angiography resulted in successful and appropriate arterial access, successful intubation of both coronary arteries, safe monitoring throughout the procedure and correct reporting of each study, with a similar level of patient satisfaction.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that nurses can, under the right supervision and governance, perform diagnostic coronary angiography to a safe, highly effective standard, which is equivalent to contemporaries.

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) remains among the leading causes of premature death in the UK, as well as the leading cause of death worldwide. In the UK, one in seven men and one in 11 women will die from CAD, which, on average, is one death every eight minutes.1 Despite advances in non-invasive diagnostic tools,2,3 invasive coronary angiography remains the gold-standard test for diagnosing CAD.4 Angiography is performed and learned by doctors in a cardiac catheterisation laboratory, or cath lab. Advanced nursing roles, supported by competency-based training, have been pioneered over the last 25 years, with emphasis on the development of specific medical skills.5 This has largely been influenced by increasing complex medical needs, costs of healthcare and the significant reduction in service provision by doctors in training.5

With this reduction of doctors in training, and the departmental support for expansion of nursing roles, we devised a local initiative to train an experienced specialist nurse to perform diagnostic coronary angiography. Our aim was to provide a safe and enhanced service and improve the cardiac day unit procedural efficiency. Here we report a direct comparison of nurse-led diagnostic coronary angiography with that delivered by a consultant cardiologist and a cardiologist in training. We directly compared quantitative procedural data, as well as qualitative data, from both a colleague and patient perspective.

Background

Buckinghamshire Healthcare serves a local population of around half a million patients, with an increasing adult population. With fewer doctors in training available in the cath lab, training a nurse to perform angiograms can support cath lab activity and efficiency in a high-quality and cost-effective manner. The aim of this study was to train a nurse angiographer to perform safe and effective diagnostic coronary angiography independently. Benefits of developing this role included enhanced service delivery for patients, better utilisation of cath lab space and reduced waiting times for patients. Development of this role was also to free up consultant cardiologists to perform other clinical duties including ward rounds, supporting patients in the emergency rooms and outpatient clinics.

We set up a nurse coronary angiographer service in 2015, in a district general hospital in Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust. In order to set up this role, approval was attained from this NHS trust. The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) encourages the development of advanced practitioner roles, providing the appropriate steps are taken within the organisation to maintain standards of practice and that nurses are aware of their personal, professional accountability, alongside demonstrating competence, for the purpose.6,7 Ethical approval was not required for this study as this was a service evaluation study.8

To ensure the appropriate steps were taken within the organisation, the first part of the approval process began with gaining consent for training from the lead cardiologist and the general manager. Further approval to practise was also gained from: consultant cardiologists – to ensure consistency and safety of training and supervision; service delivery unit – the role was presented to the cardiology team; the trust’s Nursing and Midwifery Board; Divisional Board; Drug and Therapeutic Committee – to clarify administration of inter-arterial delivery of medication by a nurse; human resources – to qualify the job description and supervision; trade unions; and New Clinical Procedure Committee.

The New Clinical Procedure Committee offered approval to commence the project, subject to the success of the diagnostic angiogram performance audit. Following successful completion of the audit, the New Clinical Procedure Committee provided final approval to practise. The job role and audit results were approved by the clinical director and the chief nurse, after being signed off by the training consultant cardiologist. The complete approval process took almost 30 months to complete before the role was established.

Alongside the approval process, the nurse training requirements included a Masters degree. It is generally acknowledged that nurse practitioners should meet competency standards benchmarked at Masters level proficiency. To perform coronary angiography, the job description stipulates the nurse practitioner must have a minimum of five years’ cath lab experience. Experience of working in the cath lab will ensure the nurse practitioner has the necessary knowledge of the cath lab, and understanding of the equipment and skills required to perform coronary angiography. The other prerequisites include an ionising radiation medical exposure regulation (IRMER) certificate to use radiation, advanced life support (ALS), assessment and diagnostic skills and non-medical prescribing.

Training in coronary angiography is conducted in the cardiac cath lab under the direct supervision of a consultant cardiologist. The British Cardiac Society (BCS) recommend doctors in training perform 250 coronary angiograms as part of the training programme. The nurse angiographer training was established similarly at 250 coronary angiograms with the consultant in the cath lab, with an additional 50 coronary angiograms with the consultant in the viewing room.

Method

A prospective audit of 250 coronary angiography procedures was undertaken in the training period between 24 September 2014 and 9 October 2015. Post-training, 143 procedures were performed between 12 October 2015 and 20 July 2016. The prospective audit was performed to explore the safety, effectiveness and quality of nurse angiographers in performing diagnostic coronary angiography. To collect the information, an audit form was created to assess each component of the procedure. This included, gaining patient consent, success in gaining arterial access, success in intubating the left and right coronary arteries, observation of haemodynamics, observation of complications and reporting the findings. Financial impact, patient satisfaction and staff perception outcomes were also audited.

Patients were included in the audit if they fulfilled any of the following criteria: planned elective diagnostic coronary angiography for angina despite maximal medical therapy, positive exercise tolerance test (ETT), assessment of coronary anatomy prior to surgery, previous coronary artery bypass grafts with recurrence of angina, post-myocardial infarction and ventricular arrhythmias. Patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) were also included in the study. Patients were excluded from the study if they had a raised international normalised ratio (INR) >2, known allergy to contrast, uncontrolled hypertension, pregnancy, stroke or ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

All elective patients were informed in their appointment letters that their procedure may be performed by a nurse. Standard coronary angiography consent was gained from each patient prior to their procedure and patients were consented for and aware that nurse practitioners would be performing their procedure. No patient declined this approach.

The nurse had to identify the reason for the procedure by reviewing the referral prior to each procedure using the patient’s notes and a brief history from the patient. The protocol for performing angiography and the patient checklist were reviewed to ensure the vital signs were within normal range, medications and pre-procedure bloods had been checked and to identify any allergies.

Current coronary angiography practice utilises the radial artery. Cases where radial access was not available were performed via the femoral artery. During the course of the audit, the department adopted radial artery as the preferred access.

The cardiology department has a single operational cath lab, with a second under construction and due to become operational in October 2017. There are five permanent interventional consultant cardiologists and one consultant cardiologist, who performs a weekly diagnostic list. Doctors in training are taught to perform angiograms in the cath lab with each of the cardiologists in turn. On sessions allocated to doctors in training, the nurse angiographer in training adopted an assistant role. The nurse angiographer in training did not impact on the training of specialist doctors.

The consultant cardiologist was immediately beside the training nurse for 250 angiograms. For the 50 angiograms post-training the consultant observed from the viewing room. Post-training, the consultant cardiologist had to be available if necessary in the hospital.

The audit assessments observed success of gaining arterial access, intubating the coronary arteries and achieving haemostasis. X-ray dose and contrast delivery were measured for each patient. The contrast dose and fluoroscopy times were compared with that of a first year cardiology registrar in training. The training nurse was assessed in their ability to observe and interpret the invasive arterial pressures and electrocardiogram (ECG) changes throughout the angiogram. Procedural success was determined by the responsible cardiologist. In cases where the nurse was unsuccessful, the procedure was undertaken by the consultant cardiologist. In addition to this prospective study, a retrospective search was performed on the trust database for vascular, cerebrovascular and renal function complications. No adverse complications were identified.

The nurse angiographer reported all angiograms performed. The treatment plan for the patients remained the responsibility of the cardiologist. Financial impact was measured by comparing the salary of a consultant cardiologist with that of a nurse’s salary. Patient satisfaction surveys were distributed to patients post-procedure. Staff responses to the nurse angiographer were collected from all members of the cath lab team. To ensure there was no impact on the training of cardiology registrars, the nurse angiographer did not train when training doctors were allocated time in the cath lab.

Results

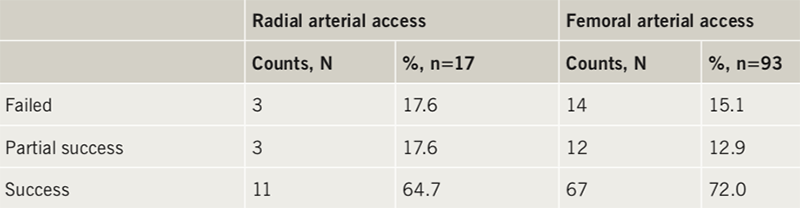

Along with patient selection and preparation, the first physical process of performing diagnostic coronary angiography is gaining vascular access, and most modern coronary angiography is preferentially done via the radial artery. We prospectively audited the ability of a nurse angiographer to appropriately cannulate the artery. We coded each attempt at appropriate arterial access as successful, failed or partially successful (as gaining arterial flow but requiring some assistance to pass the arterial sheath). Table 1 shows that the nurse angiographer was successful at independently accessing the radial artery in 64.7% of cases and the femoral artery in 72% of cases. On inclusion of partial success this increased to 82.3% for radial arterial access and 84.9% for femoral arterial access. On average, the nurse angiographer was able to achieve successful radial or femoral arterial access in 83.6% of cases. This is likely to reflect a learning curve in procedural vascular access for any nurse angiographer and the anticipation would be that this success rate would rapidly increase in relation to procedural experience.

The next stage in diagnostic coronary angiography is selective intubation of the left and right coronary arteries. In this prospective analysis, the nurse angiographer used a 5Fr Terumo diagnostic radial artery tiger catheter that is able to intubate both the left and right coronaries in most people. When using femoral access, the nurse angiographer used 5Fr Judkins left and right catheters. There were a multitude of 5Fr diagnostic catheters available for selection depending on the patient coronary anatomy. We coded each attempt at appropriate coronary intubation as successful, partially successful (as intubating with some degree of success but requiring some assistance to gain stable selective diagnostic pictures) or failed. Table 2 demonstrates that the nurse angiographer was able to intubate the left coronary artery in 89.1% and right coronary artery in 87.7% of cases. On inclusion of partial success this value increased to 97.3% for the left coronary artery and 91.5% for the right coronary artery. On average the nurse angiographer was able to successfully intubate both coronary arteries 94.4% of the time. This is also likely to reflect a learning curve in selective coronary intubation for any nurse angiographer and the anticipation would be that this success rate would rapidly increase in relation to procedural experience.

One surrogate marker for safe diagnostic coronary angiography is the amount of X-ray radiation exposure to the patient and the volume of injected contrast agent to achieve complete and satisfactory diagnostic images. Here we retrospectively compared the nurse angiographers screening time in (seconds) and the volume of contrast agent (ml) with a cardiology registrar in training with similar experience in diagnostic coronary angiography. Figure 1 demonstrates that both the screening time and amount of contrast agent were significantly lower in the nurse-led procedures compared with the cardiologist in training. This corresponded to a significant difference in the average fluoroscopic screening time of 170.1 seconds for the nurse angiographer and 324.4 seconds for the cardiologist in training. The average amount of contrast used was significantly lower for the nurse angiographer at 72.95 ml when compared with the cardiologist in training at 95.39 ml. This suggests that the nurse angiographer technique might limit the exposure of the patient to ionising radiation and nephrotoxic agents compared with the cardiologist in training.

We also conducted a detailed staff survey comparing the nurse angiographer and eight of her consultant colleagues in their perceived abilities to lead and perform diagnostic coronary angiography. All data were anonymised and collated by a third party blinded to the results. Figure 2 shows a graphic representation of the results. Questions were grouped into four categories, which included leadership, management, teamwork and interpersonal skills. Throughout all four key areas the nurse angiographer performed at the perceived level in comparison with the consultant cardiologist. Also of note is that in some areas, such as teamwork, there may be a signal towards greater performance. One may argue that this reflects an experienced nurse working directly with nursing and healthcare assistant colleagues as opposed to doctors. However, as there was only a single nurse angiographer in this study, it is more likely to reflect the personal attributes of that key individual. We also conducted a qualitative patient survey (data not shown) which gave an opportunity for patients to feedback comments of their experience with a nurse performing their coronary angiography. Most patient feedback was attributed to the role of nurses in general within the department, however, feedback that could be directly attributed to the nurse angiographer remained highly positive.

With every invasive investigation it is important to consider potential complications directly related to diagnostic coronary angiography. Table 3 shows that the nurse angiographer was able to demonstrate that she observed haemodynamic monitoring throughout 99.1% of procedures. It also shows that the nurse angiographer was able to identify procedural complications 98.1% of the time. Adequate haemostasis of the vascular access site was achieved in 97.5% of procedures. Overall, the nurse angiographer was able to successfully report all diagnostic procedures, and only required assistance in 2.8% of cases. It is particularly interesting to note that the nurse angiographer did not have any post-procedural complications. These included those related to arterial access site, such as bleeding, pseudoaneurysm, or stroke, dissection or cardiac tamponade. There were no deaths accountable to the nurse angiographer performing coronary angiography.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that nurses can, under the right supervision and governance, perform diagnostic coronary angiography to a safe and highly effective level. Limited studies have previously been performed, but these conclude that nurse coronary angiographers are capable of acquiring the skills to safely perform these procedures.9-11 In order to maintain competence to practise coronary angiography, the British Cardiovascular Society state a minimum of 100 procedures a year must be performed. In setting up and developing this nurse angiographer role we have achieved and exceeded these recommendations.

Training nurses does not impede on training doctors. Throughout the study, the nurse training in angiography was conducted only when there were no doctors in training in the cath lab. Training nurses in coronary angiography does not impede on doctors in training and since completion of training, the nurse angiographer has been able to assist in training doctors in the practical skills of performing coronary angiography.

Medicolegal responsibility is an essential consideration, as the legal implications of nurse angiography and medical cover is a potential area of concern. Nurses performing angiograms must have a consultant cardiologist within the hospital in case urgent assistance is required. Cardiologists delegating angiography to nurses must be satisfied that the nurse performing coronary angiograms is competent and has had the appropriate training and supervision to perform coronary angiography. The doctor should retain ultimate responsibility for the management of these patients.12 Nurses performing diagnostic angiography must be competent to decline any duties unless they are safe to perform the roles and remain accountable for their practice in accordance with the Nursing and Midwifery Code of Conduct.13 The coronary angiographer responsibilities must be updated to comply with the nurses’ job descriptions and continuously appraised. Nurses’ indemnity and any claims of negligence are covered by the NHS trust indemnity, providing the appropriate steps of training, supervision and support of the organisation are evident.

Throughout the training period the nurse was committed to continuing the existing workload of managing the cardiac day unit. One limitation of this observational study is the lack of real direct comparison, the data were not available to compare the safety and efficacy of diagnostic coronary angiography performed by doctors in training. Therefore, a more robust direct comparative study is required, which would answer questions such as time taken to achieve competence and healthcare cost analysis.

However, we feel that this study illuminates the potential to utilise experienced nurses and serve as a road map for developing nurse coronary angiographer roles in other centres. This study demonstrates that nurses can perform coronary diagnostic angiography safely, effectively and of high quality.

Key messages

- This study demonstrates that supervised trained specialist nurses can have extended roles in the safe and effective delivery of diagnostic coronary angiography

- This study highlights a blueprint for the reproduction of a nurse angiographer role in future centres interested in developing these skills

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgement

We thank Professor Tom Quinn for guidance and support for publishing this work.

Study approval

Ethical approval was not required for this study as this was a service evaluation study. Further details of other approval are given in the text.

Consent

Patient consent was obtained.

Editor’s note

There is no question that a nurse can do diagnostic coronary angiography as well as a junior doctor; the problem today is, now we have CT Fractional Flow Reserve (CT FFR), the need for diagnostic angiography is rapidly declining. If, therefore, nurses perform the majority of coronary angiograms, there will not be an opportunity to train doctors so that they can ultimately take on the complex cases or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). KF

An editorial by Patterson and Redwood on nurse-led angiography can be found here.

References

1. British Heart Foundation Centre on Population Approaches for Non-Communicable Disease Prevention. Cardiovascular disease statistics, 2015. London: British Heart Foundation, 2015. Available from: https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/publications/statistics/cvd-stats-2015

2. Davies MJ, Newton JD. Non-invasive imaging in cardiology for the generalist. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2017;78:392–8. https://doi.org/10.12968/hmed.2017.78.7.392

3. Taylor AJ, Cerqueira M, Hodgson JM et al. ACCF/SCCT/ACR/AHA/ASE/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SCMR 2010 appropriate use criteria for cardiac computed tomography. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the American College of Radiology, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2010;4:407.e1–407.e33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcct.2010.11.001

4. MacLachlan H, Thomas R, Langtree J et al. Is there a role for a local inpatient CT coronary angiography service in selected patients with acute coronary syndrome? A cohort analysis of inpatient tertiary centre referrals for invasive coronary angiography. Open Heart 2016;3:e000389. https://doi.org/10.1136/openhrt-2015-000389

5. Gray A. Advanced or advancing nursing practice: what is the future direction for nursing? Br J Nurs 2016;25:8, 10, 12–13. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2016.25.1.8

6. Iglehart JK. Expanding the role of advanced nurse practitioners – risks and rewards. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1935–41. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMhpr1301084

7. Pearce L. Recognition for advanced nurse practitioners. Nurs Stand 2017;31:38–9. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.31.24.38.s42

8. Dorling H, Cook A, Ollerhead L et al. The NIHR Public Health Research Programme: responding to local authority research needs in the United Kingdom. Health Res Policy Syst 2015;13:77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-015-0068-x

9. Morgan R, Wallis L, Belli AM. Diagnostic angiography performed by nurses. Br J Radiol 2001;74:648–50. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.74.883.740648

10. Chalmers N, Conway B, Andrew H et al. Evaluation of angiography performed by radiographers and nurses. Clin Radiol 2002;57:278–80. https://doi.org/10.1053/crad.2001.0743

11. Boulton BD, Bashir Y, Ormerod OJ et al. Cardiac catheterisation performed by a clinical nurse specialist. Heart 1997;78:194–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.78.2.194

12. General Medical Council. Professional conduct and discipline: fitness to practise. London: GMCl, 1993.

13. Nursing & Midwifery Council. The code. Professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates. London: NMC, 2015. Available from: https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/nmc-publications/nmc-code.pdf