The UK cardiology specialist training programme utilises the National Health Service (NHS) e-Portfolio to ensure adequate progression is being made during a trainees’ career. The NHS e-portfolio has been used for 15 years, but many questions remain regarding its perceived learning value and usefulness for trainees and trainers. This qualitative study in the recent pre-COVID era explored the perceived benefits of the NHS e-Portfolio with cardiology trainees and trainers in two UK training deaneries. Questionnaires were sent to 66 trainees and to 50 trainers. 50% of trainees felt that their development had benefited from use of the ePortfolio. 61% of trainees found it an effective educational tool, and 25% of trainees and 39% of trainers found the ePortfolio useful for highlighting their strengths and weaknesses. 75% of trainees viewed workplace based assessments as a means to passing the ARCP. The results show that the NHS ePortfolio and workplace based assessments were perceived negatively by some trainees and trainers alike, with many feeling that significant improvements need to be made. In light of the progress and acceptance of digital technology and communication in the current COVID-19 era, it is likely to be the time for the development of a new optimal digital training platform for cardiology trainees and trainers. The specialist societies could help develop a more speciality specific learning and development tool.

Introduction

Postgraduate cardiology training in the UK consists of three years of internal medicine training followed by five years of cardiology specialty training, which comprises three years of core specialty training (ST3,4,5) and a further two years of subspecialty training (ST6,7).1,2

The current system has been developed through a series of modifications after its inception in August 2008. It is an electronic portfolio of assessments and competencies, which was launched by the UK National Health Service (NHS) in August 2005, in an effort to support the achievement and education of healthcare professionals.3 These assessments are done in the form of workplace-based assessments (WBAs), which has evolved with the development of competency-based medical training since 2004, and the 2005 introduction of ‘Modernising Medical Careers’.4-6 They are now the mainstay of assessment for trainees, and the central tool for tracking trainees’ progression.3,7The 2016 amendment of the cardiology curriculum saw the introduction of several reformed WBAs, which focus on the completion of different competencies required for specialty training.8 However, 15 years on from the creation of the ePortfolio, its effectiveness as an instrument to support and improve trainee performance still polarises opinions. Studies also show that trainees feel that the focus in recent years on objective assessment of specific competencies has fuelled a ‘tick-box’ mentality, preventing more practical, self-directed learning.

In an effort to respond to criticism, the structure of the ePortfolio was reviewed and changed in 2012,5 with the aim of improving the quality and quantity of feedback that educational supervisors gave to their core medical trainees (CMTs). Our study comes 10 years after the initial introduction of the ePortfolio and six years on from the last significant qualitative study of trainees’ experience with the ePortfolio. It aims to determine whether current cardiology trainers and trainees perceive benefit from the reformed ePortfolio.

Method

The study used a qualitative methodology consisting of semi-structured interviews, a focus group and questionnaire survey with freetext feedback. Insights gained from both groups were then used to aid the development of two separate questionnaires for trainers and trainees.

Focus group discussion and semi-structured interviews

Trainers were recruited for the focus group discussion via an email letter. Participation was voluntary and participants could withdraw from the study at any time. Five trainers consented and were available for the focus group discussion.

The interviews explored experiences with the use of WBAs, addressing different topic areas explored from previously published work regarding their educational value.

Questionnaire survey

Trainers and trainees from two UK training regions were invited to participate in the questionnaire survey. The two regions (A and B) consisted of training hospital clinical sites with 66 trainees (28 trainees in region A and 38 in region B) and a training committee of 50 trainers. The study was undertaken towards the end of the training year, which ensured that all participants had been involved in ePortfolio/WBA assessments.

Results

Semi-structured interviews and focus group

Five trainers and three trainees participated in the focus group and semi-structured interviews, respectively.

Questionnaire surveys

Questionnaires were sent out to 66 trainees in the two UK training regions and 38 responses were obtained (58% response rate). There were 26 responses received from trainers, of whom 20 were trainers for more than five years.

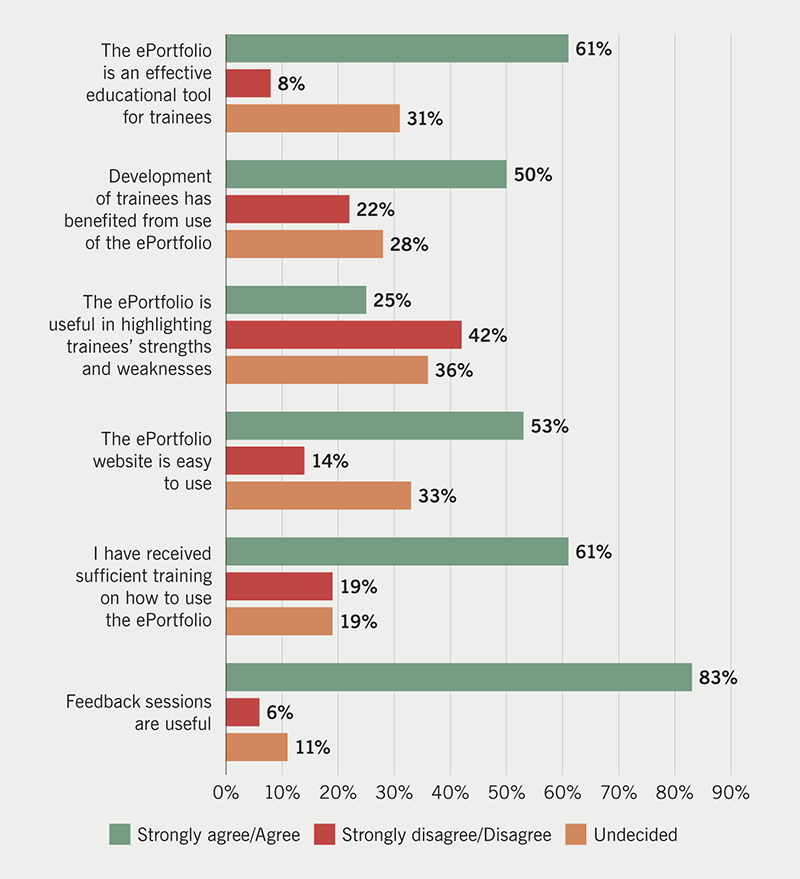

The trainee responses showed that 53% found the ePortfolio website easy to use with 61% trained or knowledgeable in its use. Furthermore, 61% felt that the ePortfolio was an effective educational tool for trainees, with 39% either unsure or finding it non-effective. Of the trainees, 25% felt that the ePortfolio was useful for highlighting their strengths and weaknesses, with 42% disagreeing or strongly disagreeing, and 36% were undecided (figure 1).

With regard to workplace assessments, 75% viewed workplace assessments as a means of ‘passing the year’ and 17% viewed it primarily as a useful learning exercise. Assessors were felt to be usually present by 75%, with verbal feedback given immediately by 69%, and 42% felt the time given for feedback was adequate but the immediate documentation of the feedback on the trainee ePortfolio was only done in 19%. There were 58% who felt that their clinical practice had improved on the basis of feedback from WBAs.

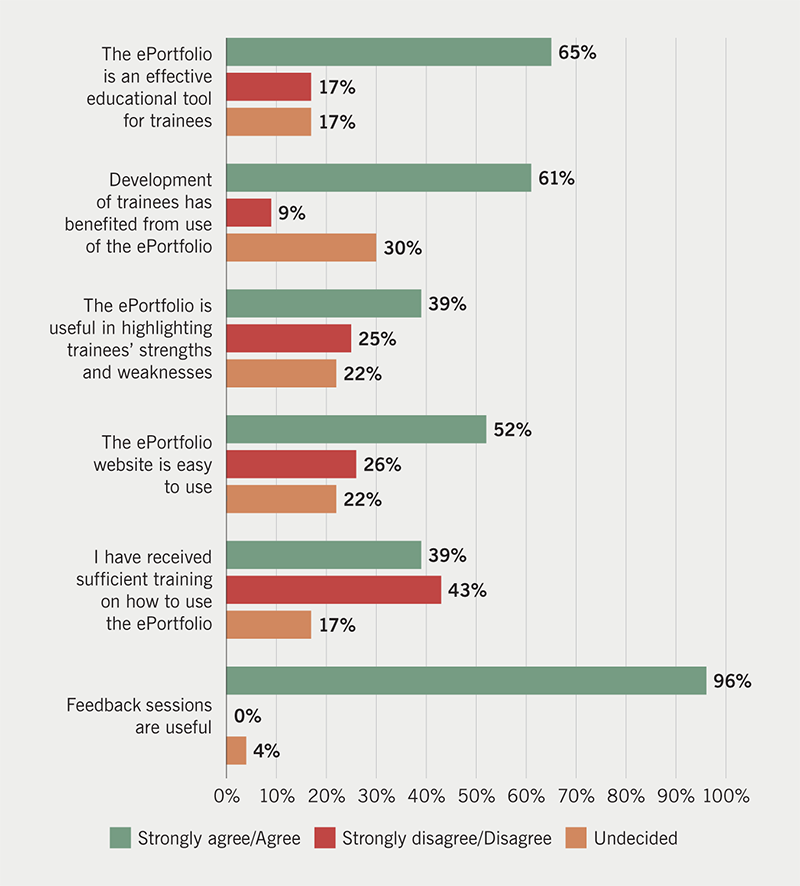

On the other hand, 52% of trainers felt the website was easy to use, and only 39% felt they had received adequate training in the use of the ePortfolio (figure 2). The contents of the trainees curriculum were familiar to 61%, and 61% thought that their trainees development had benefited from it (figure 2).

Discussion

Our study found that three quarters of trainees saw WBAs as ‘tick-box’ exercises, rather than an effective training tool. The learning value of some WBAs, particularly the case-based discussion (CBD) and mini-clinical evaluation exercise (mini-CEX) were felt to be less useful than direct observation of procedural skills (DOPS) by both trainers and trainees. This issue is aggravated by the fact that final progression review meetings focus on assessing completion of the required number of assessments rather than their quality.

Some trainees find the feedback they receive from the trainers to be vague and unbeneficial.3 The electronic forms are filled in retrospectively after the case and, therefore, based on recall of the assessment and on requests that could be as long as six months later, thus, making both the assessment less accurate and the feedback minimal and unhelpful. In addition, it is felt that more feedback and learning occurs in the routine activity, which is not captured in the setting of WBA. Improvement in technology was felt to be necessary to help with time constraints to providing and recording feedback. A more accessible and user-friendly ePortfolio smart app could provide a more portable means of accessing the portfolio, which could make it easier for the trainer to record more immediate feedback.

One approach that is more of a pedagogic change to the current system has been suggested by ten Cate and Scheele.9 This is the mapping of principal clinical responsibilities, also called entrustable professional activities (EPA), to the core competencies most important to each responsibility. It is, thus, clinical activity that trainees are entrusted to perform without supervision and, therefore, deemed competent. An outcome such as ‘function at the level of a ST4 cardiology registrar’ could be broken down into EPAs such as ‘deliver a ward round independently’, which could then be linked to the competencies at level of expectation based on year of training. This EPA-based framework for curriculum design shows the integration between a competency-based curriculum and real tasks. This approach has already been adopted in many countries such as the US, Canada, Germany, Australia and New Zealand.9,10 This system would also have the advantage of making WBAs part of the work environment and daily routine, instead of isolated check-ups and a tick-box exercise.

Conclusion

While there is educational benefit to be derived from the ePortfolio/WBA system, it is hampered by implementation practices that need to be optimised towards higher educational benefit. This could potentially be improved by more clear guidelines on how to effectively use the ePortfolio and WBA system, as well as making technological improvements. A redesigned specialty specific ePortfolio with involvement of specialty societies and pedagogic approaches, such as the use of EPAs should also be considered.

Key messages

- Trainees view workplace-based assessments as a means to passing the annual review of competence progression (ARCP)

- The current NHS ePortfolio interface needs to be more ‘user friendly’. A consideration of a new digital platform is made more timely by the uptake of telemedicine and virtual healthcare tools in the current COVID-19 era

- More training should be provided for supervisors and trainers on how to fully utilise the ePortfolio

- A redesigned cardiology specific ePortfolio with specialty society involvement is likely to provide a better and more cardiology-oriented training platform

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Study approval

The research proposal adheres to the six guiding principles for research (respect for persons, beneficence, justice, confidentiality, non-maleficence, veracity) as outlined in the Belmont report (1979). The study was approved by the Liverpool University Research Ethics Committee. The training programme directors for North West and Mersey regions were included as study gatekeepers for all recruitment processes.

References

1. Gale C, Simpson H, Myerson S et al. The 2007 curriculum in cardiology: an overview for trainees and trainers. Br J Cardiol 2007;14:286–8. Available from: https://bjcardio.co.uk/2007/11/the-2007-curriculum-in-cardiology-an-overview-for-trainees-and-trainers/

2. Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board. Shape of training and the physician training model. Available at: https://www.jrcptb.org.uk/imt

3. Tailor A, Dubrey S, Das S. Opinions of the ePortfolio and workplace-based assessments: a survey of core medical trainees and their supervisors. Clin Med J R Coll Physicians London 2014;14:510–16. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.14-5-510

4. McConnell M, Sherbino J, Chan TM. Mind the gap: the prospects of missing data. J Grad Med Educ 2016;8:708–12. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-16-00142.1

5. Fuller G, Simpson IA. “Modernising Medical Careers” to “Shape of Training” – how soon we forget. BMJ 2014;348:g2865. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g2865

6. Gofton W, Dudek N, Barton G, Bhanji F. Workplace-based assessment implementation guide: formative tips for medical teaching practice. 1st ed. Ottawa: The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, 2017. Available from: http://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/documents/cbd/wba-implementation-guide-tips-medical-teaching-practice-e.pdf

7. Tham TCK, Burr B, Boohan M. Evaluation of feedback given to trainees in medical specialties. Clin Med J R Coll Physicians London 2017;17:303–06. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.17-4-303

8. Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board. Specialty training curriculum for cardiology August 2010 (amendments 2016). Available from: https://www.jrcptb.org.uk/documents/2010-cardiology-curriculum-amendments-2016

9. ten Cate O, Scheele F. Competency-based postgraduate training: can we bridge the gap between theory and clinical practice. Acad Med 2007;82:542–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31805559c7

10. European Society of Cardiology. ESC e-Learning Platform. Professional development module. Available at: http://learn.escardio.org/general-cardiology/professional-development.aspx