Dear Sirs,

Implantation of cardiac devices is increasing at a tremendous rate. Rate of implantation of permanent pacemakers (PPM) alone is rising at a rate of 4.7% per decade.1 Implantation of these devices can transiently affect driving ability and, therefore, require temporary driving restrictions. It is a responsibility of the healthcare professionals to inform their patients of these restrictions to improve the safety of the patient and general public.2,3

Following the article by Drs Inderjeet Bharaj et al.4 asking whether the medical profession is doing enough to give patients appropriate advice about driving after certain cardiac conditions, we are writing to share our own protocol. Hereford County Hospital is a 208-bed district general hospital that implants around 200–250 cardiac devices yearly, including complex cardiac devices, such as implantable cardiac defibrillator (ICD) and cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT) devices. Many implants are in emergency inpatients and our aim was to increase the provision of appropriate driving advice upon discharge.

Method and measurements

Baseline data were collected for inpatient cardiac device implantation from 1 February 2020 until 30 April 2020. Patients were identified from the online hospital database. Electronic discharge summaries were reviewed to assess the provision of Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) advice for the patients undergoing insertion of PPM, ICDs and CRT devices. An Excel spreadsheet was used to record the collected data. Patients who had outpatient day-case procedures were not included.

Plan, do, study, act (PDSA) cycle 1

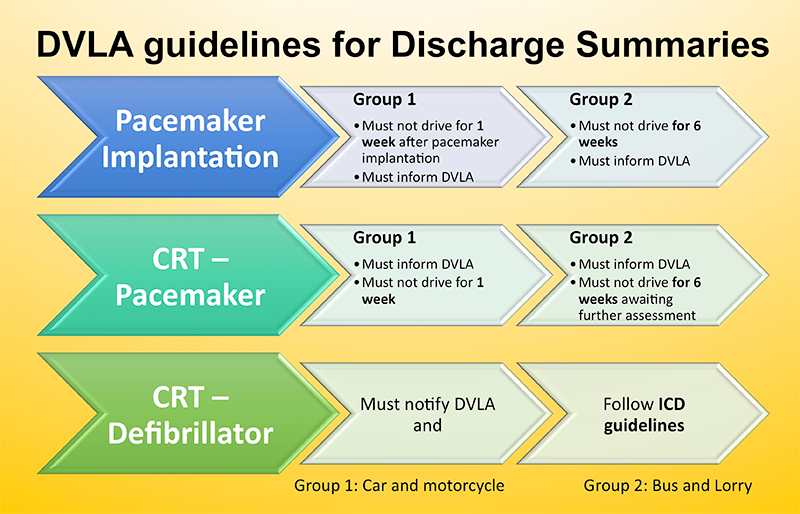

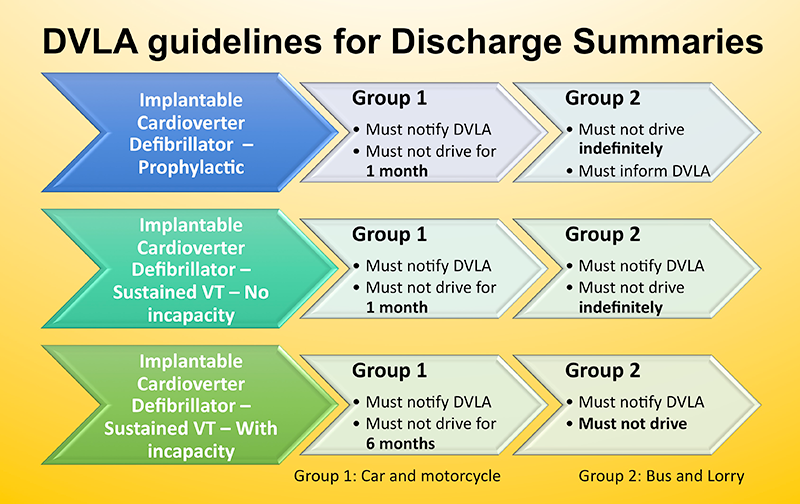

Informal teaching was conducted for junior doctors and a standardised DVLA advice template (figures 1 and 2) was printed in the cardiology ward and coronary care unit. Information leaflets were handed out. This was followed by data collection until 31 May 2020.

PDSA cycle 2

Formal teaching was delivered to the junior doctors and an electronic version of the DVLA advice template was sent via email. Data collection was done until 30 June 2020.

PDSA cycle 3

Re-iteration of the importance of these guidelines among junior doctors by informal teaching and distribution of electronic versions to their mobiles for ease of access. Data collection was done at the end of July 2020.

PDSA cycle 4

Incorporation of the DVLA advice leaflet in the induction pack and formal teaching for the new batch of junior doctors. Data collection was completed on 31 August 2020.

Results

Baseline data revealed 29 patients underwent implantation of cardiac devices: six of them received driving advice upon discharge, i.e. 20.7%, and among them, four were in accordance with the DVLA guidelines.

After introduction of the standardised DVLA instruction template, we observed marked improvement in this percentage. Five of the six patients who underwent cardiac device implantation had appropriate written DVLA advice given upon discharge, i.e. 83.3%. In addition to the previous steps, measures taken in cycle 2 resulted in 100% compliance by the junior doctors and these were maintained in cycle 3 (n=8 for cycles 2 and 3).

In August, measures taken after induction of new doctors helped to maintain this percentage at 100%. All the five patients who had cardiac device implantation in August received correct driving advice upon discharge.

Discussion

Implantable cardiac devices improve survival of patients with risks of sudden cardiac death. However, these patients are still at risk of sudden incapacitation, which can pose risk to themselves and others. DVLA instructions for Group 1 and Group 2 licence holders, following insertion of a cardiac device, are to minimise these risks.2 This, however, is seldom re-iterated on discharge. Moreover, documentation of it is commonly lacking. Studies and quality improvement projects, focusing on provision of DVLA advice in acute coronary syndromes, have demonstrated similar results as well.4,5

We have found the introduction of measures like teaching, distribution of leaflets and formation of a standardised DVLA advice template to be helpful in improving this documentation. Moreover, the ease of access that the junior doctors get, with the availability of electronic copies over their phones, further helps it. Finally, a simple strategy like incorporation of these measures in the induction of new doctors helps to maintain sustainability.

These educational measures and simple strategies can be utilised in trusts across the UK to improve the quality of care being delivered to patients and promote patient safety.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Study approval

Not required.

Arsalan Khalil

Internal Medicine Trainee

Tamara Naneishvili

Cardiology Registrar

Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, Mindelsohn Way, Birmingham, B15 2GW

Abigail Mayo-Evans

Physician Associate

James Glancy

Cardiology Consultant

Hereford County Hospital, Wye Valley NHS Trust, Stonebow Road, Hereford, HR1 2ER

References

1. National Institute of Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (NICOR). National Audit of Cardiac Rhythm Management Devices: 2016/2017 Summary report. London: NICOR, 2019. Available from: https://www.nicor.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/CRM-Report-2016-2017.pdf

2. Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA). Assessing fitness to drive: a guide for medical professionals. Swansea: DVLA, 2016. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/assessing-fitness-to-drive-a-guide-for-medical-professionals

3. General Medical Council (GMC). Good medical practice. Manchester: GMC, 2013. Available from: https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/good-medical-practice—english-20200128_pdf-51527435.pdf

4. Bharaj I, Sethi J, Bukhari S, Singh H. Driving after cardiac intervention: are we doing enough? Br J Cardiol 2021;28:19–21. https://doi.org/10.5837/bjc.2021.009

5. Naneishvili T, Khalil A, Mayo-Evans A, Glancy J. Improving DVLA advice provided to the patients with acute coronary syndrome upon discharge. Future Healthc J 2021;8:fhj.2020-0196. https://doi.org/10.7861/fhj.2020-0196