AS awareness and detection

Low detection rates of valvular heart disease (VHD) and AS are widespread, as many patients are diagnosed only when symptoms occur.5,8 The OxVALVE study (https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/37/47/3515/2844994) showed that 51% of the population aged 65 years and older have undiagnosed VHD, and 1.3% have undiagnosed AS.5 Among the general population, a lack of awareness exists of AS and its symptoms. In a European survey of over 12,000 people aged 60 years and over, only a fifth were aware of VHD, and less than 4% could provide an accurate description of AS.9 National campaigns are recommended to raise public awareness of VHD symptoms and encourage people to contact their primary care physicians.10,11

Specific education and training are also required within the primary care setting to improve recognition of severe AS ‘red flag’ symptoms.10 Common symptoms of severe AS, including breathlessness and fatigue, are often regarded as general signs of ageing and may not be recognised as early warning signs for severe AS in elderly patients.

Most Europeans aged 60 or older report not receiving a regular stethoscope check from their general practitioner (GP), despite their wish for VHD to be part of their standard health checks.9 Improving auscultation delivery and competencies should be a key goal of educational initiatives within primary care. Active community screening using auscultation combined with new technologies, such as digital stethoscopes or hand-held ultrasound systems, can effectively detect patients with AS earlier in their disease. In the UK, screening elderly patients for AS during routine vaccination visits is feasible using inexpensive and straightforward diagnostic measures, including heart auscultation and hand-held two-dimensional (2D) ultrasound systems, which could identify an estimated 130,000 cases of moderate AS annually.12 In Spain, hand-held 2D cardiac ultrasonography can be helpful for rapidly identifying patients with echocardiographic abnormalities and those who may not require further echocardiographic follow-up.13 Notably, this technology can be used by family doctors or specialist-trained clinical scientists in a community setting.13,14

Diagnosis and referral

Access to high-quality echocardiographic imaging is essential for the early diagnosis of severe AS, reducing waiting lists, and allowing prioritisation of patients. A broad base of echocardiography resources is necessary to support the AS patient pathway. The Global Heart Hub recommends using data-based workforce planning to increase the number of physicians and physiologists performing quality echocardiography.10

Echocardiography should be used as early as possible to confirm an AS diagnosis and evaluate disease severity. It should be offered to symptomatic patients within two weeks of referral and to asymptomatic patients within six weeks.10,11

Various locations can potentially provide echocardiography, including community settings, referring hospitals, Heart Valve Clinics, or Heart Valve Centres. It is vital that consistent imaging standards and reporting are met to ensure correct AS grading and to avoid the need for repeat testing. The British Society of Echocardiography has outlined the minimum dataset required for transthoracic echocardiography assessment and reporting in patients with suspected AS (see table 1).15,16 According to these guidelines, echocardiographic images should be stored in a file identified by the patient’s name, hospital number and date of birth, and include details of the echocardiographer.16 Importantly, echocardiographic images should be available for all key stakeholders to avoid repetition, facilitate rapid decision-making, and allow feedback for referring physicians as part of their training.

Table 1. Proposed minimum requirements for echocardiographic assessment and reporting for patients with suspected aortic stenosis (AS)15,16

| Echocardiographic views to be obtained |

|

| Minimum dataset |

Demographics

|

Aortic valve morphology

|

Left ventricular outflow tract

|

AS severity

|

Aortic regurgitation

|

Aorta

|

Additional prognostic markers

|

| Table compiled from data in Ring L et al.15 and Robinson S et al.16 with permission under Creative Commons CC BY license https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ |

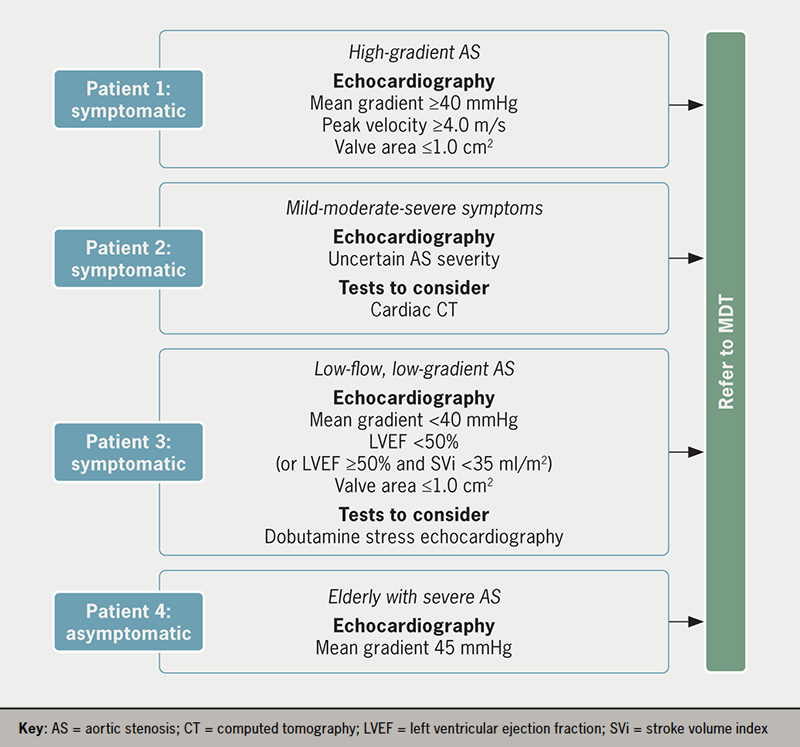

Once the minimum dataset for echocardiographic imaging is obtained alongside any additional diagnostic tests, the patient can be referred to the Heart Team for a treatment decision (figure 1). Typical profiles of patients referred to the Heart Team are outlined in figure 2.

Even when patients are diagnosed with severe AS, many do not go on to receive appropriate treatment. A European survey demonstrated that one in five patients with severe symptomatic AS did not proceed to any intervention, despite its Class I recommendation in the latest European Society of Cardiology/European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (ESC/EACTS) guidelines (https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/43/7/561/6358470?login=false#364291358).6,17 The most common reasons for non-referral for aortic valve intervention were the short life expectancy or the physician’s consideration of the patient as inoperable or high risk.18 Substantial advances in TAVI technology, operator (and institutional) experience and meticulous procedure planning, with systematic use of CT scanning, have led to significant improvements in outcomes and, therefore, prognosis and quality of life for elderly patients, including those with comorbidities.2

Educational initiatives should be developed for primary care to facilitate patient referral. Decision support tools and workflows, for example, can tackle hesitancy in referring patients early after symptom onset or when symptoms are not severe. Untreated, symptomatic, severe AS has a poor prognosis and low survival rate,19 and a recent study demonstrated that even asymptomatic patients benefit from early treatment instead of conservative care.20 It is thus paramount to ensure physicians are aware of the benefits of treating severe AS in elderly patients and those with comorbidities.

Establishing a standardised network for management of AS

An integrated network ideally provides the management and treatment of patients with severe AS, comprising:21

- Primary care physicians and hospital referral centres involved in early diagnosis and referral of patients

- Heart Valve Clinics involved in early detection, referral, patient monitoring and network support, as required

- Heart Centres, responsible for delivering treatment via the specialist Heart Team.

As discussed below, optimising how these functions operate within the network is key to delivering timely and effective patient care. The facilities and personnel at individual referral centres, Heart Valve Clinics and Heart Valve Centres vary considerably. Therefore, it is crucial to tailor the treatment pathway, ensuring the appropriate local infrastructure and resources are available for timely referral.

Role of the Heart Valve Clinic

Heart Valve Clinics are specialist, multidisciplinary outpatient clinics providing centralised management to patients with VHD.22,23 While some are located in large Heart Centres, they can also be in district hospitals or community settings, providing support to patients and primary care physicians at a more local level. They have arisen in response to the rapidly growing numbers of patients with VHD and an increased need for local specialist knowledge to ensure patients are diagnosed and referred for treatment as quickly as possible.

Key roles served by Heart Valve Clinics include:21

- Initiation and coordination of care between the community, referring hospitals and heart centres throughout the patient pathway, including post-discharge

- Support for detection and diagnosis of VHD and specialist imaging services

- Education of major stakeholders, such as patients and healthcare professionals, both before and after treatment

- Involvement with Heart Teams.

Heart Valve Clinics are at the centre of the VHD network and improve efficiency by tackling the significant variability in referral habits among general cardiologists.24,25 Monitoring patients via the Heart Valve Clinic helps detect symptoms earlier and at less severe stages.25 This is especially important for patients with severe AS, as the severity of preoperative symptoms is a prognostic indicator for postoperative survival.25

Reducing redundancy and repetition during diagnosis is essential for a streamlined patient pathway. Heart Valve Clinics can provide a one-stop service for diagnostics and testing, including specialist support for echocardiographic imaging.21,24 To achieve consistency, these clinics should also provide education and training for clinicians in primary care settings and investigate opportunities for delivering echocardiography in community and hospital settings.24

Heart Valve Clinics are also responsible for providing dedicated care throughout the patient pathway, including delivering a comprehensive and individualised management plan for the patient.24 Ideally, patients should have a single point of contact within the clinic, such as a nurse practitioner, who can coordinate care for patients as they progress along the treatment pathway.26 This is particularly beneficial if the patient has an early stage disease and requires monitoring before referring for intervention. In addition, the Heart Valve Clinic must monitor patients and manage their care post-discharge to identify and address potential complications appropriately.

Significantly, Heart Valve Clinics not only benefit patient care but also have the potential to reduce overall costs in the treatment of AS by reducing follow-up costs for patients before and after intervention.27

Role of Heart Valve Centres and the Heart Team

Heart Valve Centres provide multidisciplinary treatment decision-making and treatment. These centres must have demonstrable experience in treating VHD, including sufficient volume of procedures (e.g. a minimum of 100 TAVI procedures per year and 200 surgical procedures per year in France) and transparency of efficacy and safety outcomes to encourage patient flow.28 The recommended components of a Heart Valve Centre are set out in the latest ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of VHD (https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/43/7/561/6358470?login=false#364291358), and include:17

- A multidisciplinary Heart Team

- Provision of the entire spectrum of surgical and transcatheter heart valve procedures

- Multimodality imaging capabilities

- A Heart Valve Clinic for outpatient and follow-up management

- Review procedures for evaluation of outcomes and quality of care

- Educational programmes targeting patients, primary care, operators, diagnostic and interventional imagers and referring cardiologists.

The multidisciplinary Heart Team is the central treatment decision-making body within the network, comprising a clinical cardiologist, interventional cardiologist, cardiac surgeon, imaging specialist with expertise in interventional imaging, cardiovascular anaesthesiologist, and additional specialists.17,29 With its combined expertise, the Heart Team facilitates a balanced assessment of patients, even where supportive data are limited, and allows for effective allocation of resources to maximise patient benefit.17,29

The Heart Team should discuss all patients referred for treatment at multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings. However, treatment of standard cases may be aligned to pre-agreed internal protocols depending on the availability of local resources. In the COVID-19 era, Heart Team meetings are usually virtual, allowing referring physicians to dial in and present patients directly to the Heart Team. A single point of entry to the Heart Team should be established to reduce referral barriers while ensuring the team functions efficiently. This contact can provide primary care physicians with a clear pathway for referral of patients to the Heart Team and ensure all appropriate data requirements are in place. This can also aid ongoing education and training of referring teams.

To optimise patient outcomes, treatment needs to be delivered at the appropriate time for the patient. Patients with early-stage disease, for example, may not be considered for treatment by the MDT and may be monitored by the Heart Valve Clinic until treatment is deemed appropriate and the patient is referred back to the MDT.14 For patients identified by the MDT as requiring treatment, the management pathway should be individualised, considering patients’ preferences, as highlighted in ESC/EACTS treatment guidelines (https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/43/7/561/6358470?login=false#364291358).17 Treatment must also be considered in the context of patients’ expected future requirements. In the case of TAVI, procedural access, valve durability, coronary access and the potential need for permanent pacemaker implantation or a future transcatheter heart valve (THV)-in-THV procedure must be considered before treatment decisions are taken.30 Similar considerations apply when the Heart Team opts for surgical aortic valve replacement, where prosthesis choice and positioning should take into account available durability data for that specific valve and the feasibility of a potential THV-in-valve procedure.30

Clear communication between referring physicians, the Heart Valve Clinic, and the Heart Valve Centre throughout the treatment pathway is essential. The key stakeholders should share information on diagnostics, imaging, treatment outcomes, and pre-and post-procedural monitoring. This ensures that patients are optimally managed throughout the process and allows feedback and training from specialists to referring physicians/centres to encourage future timely referrals. A ‘Contact Coordinator’ could be assigned to ensure these communication pathways are accessible and manageable for all and appropriate to the local infrastructure and resources.

Conclusion

With an ever-increasing burden of AS among the population, the issues of low rates of AS detection and referral of patients to specialist centres need to be addressed as soon as possible to ensure early, effective treatment. This will require a concerted effort to reshape existing treatment pathways for AS based on current best practices and in line with ESC/EACTS treatment guidelines (https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/43/7/561/6358470?login=false#364291358).

Promoting informed health and care decisions among healthcare professionals, patient organisations, and researchers can facilitate rapid diagnosis and treatment for patients with AS.10 Key targets for this initiative are to ensure:

- Greater awareness of AS symptoms among the public and primary care professionals through public awareness campaigns and educational initiatives for primary care

- Introduction of quality standards for diagnostics and detection

- Clear structures and communication pathways for rapid referral of patients to Heart Teams

- A standardised network of healthcare professionals to optimise the patient pathway according to local infrastructure and resources, with Heart Valve Clinics at the centre of the pathway.

Key messages

- Despite effective treatment options, many patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS) remain undiagnosed or suffer delays in referral for treatment, leading to poor outcomes

- Increasing awareness of early AS symptoms among the public and healthcare professionals, and introducing routine auscultation in primary care, can improve its early detection

- Offering prompt echocardiography facilitates early diagnosis and referral, but it should meet quality standards to avoid misdiagnosis and the need for repetition

- The optimisation of patient detection, referral and treatment of severe AS requires a streamlined patient pathway based on a standardised network of healthcare professionals, and ensuring there are appropriate local infrastructure and resources needed to accomplish this objective

Conflicts of interest

VD has received speaker fees from Abbott Vascular, Edwards Lifesciences, GE Healthcare, Medtronic, and Novartis, and consultancy fees from Novo Nordisk. PP has received funding from Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Pi-Cardia, and Cardiac Phoenix for echocardiography core laboratory analyses and research studies in the field of transcatheter valve therapies, for which he received no personal compensation; he has received lecturer fees from Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic. FS has participated in advisory boards, and received lecturer fees from Abbott Vascular, Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic. NR: none declared.

Funding

PP holds the Canada Research Chair in Valvular Heart Disease, supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada).

Victoria Delgado

Cardiologist and Assistant Professor of Cardiology

Heart Institute, Department of Cardiology, University Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, 08916 Badalona, Barcelona, Spain

Philippe Pibarot

Head of Cardiology Research and Canada Research Chair in Valvular Heart Disease

Québec Heart and Lung Institute, Laval University, Québec, Canada, G1V 4G5

Neil Ruparelia

Consultant Cardiologist

Hammersmith Hospital, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, DuCane Road, W12 0HS, London, UK

Francesco Saia

Interventional Cardiologist

Cardio-Thoracic-Vascular Department, IRCCS University Hospital of Bologna, Policlinico S. Orsola (Pav. 23), Via Massarenti, 9 – 410138 Bologna, Italy

Correspondence to:

[email protected]

Articles in this supplement

Introduction: overcoming barriers to treating severe aortic stenosis

The past, present and future of aortic stenosis treatment

Ensuring continuous and sustainable access to aortic stenosis treatment

References

1. Auffret V, Lefevre T, Van Belle E et al. Temporal trends in transcatheter aortic valve replacement in France: FRANCE 2 to FRANCE TAVI. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:42–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.053

2. Carroll JD, Mack MJ, Vemulapalli S et al. STS-ACC TVT registry of transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:2492–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.09.595

3. Mack MJ, Leon MB, Smith CR et al. 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement or surgical aortic valve replacement for high surgical risk patients with aortic stenosis (PARTNER I™): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385:2477–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60308-7

4. Siontis GCM, Overtchouk P, Cahill TJ et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation vs. surgical aortic valve replacement for treatment of symptomatic severe aortic stenosis: an updated meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2019;40:3143–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz275

5. d’Arcy JL, Coffey S, Loudon MA et al. Large-scale community echocardiographic screening reveals a major burden of undiagnosed valvular heart disease in older people: The OxVALVE Population Cohort Study. Eur Heart J 2016;37:3515–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw229

6. Eugene M, Duchnowski P, Prendergast B et al. Contemporary management of severe symptomatic aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;78:2131–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.864

7. Joseph J, Kotronias RA, Estrin-Serlui T et al. Safety and operational efficiency of restructuring and redeploying a transcatheter aortic valve replacement service during the COVID-19 pandemic: The Oxford experience. Cardiovasc Revasc Med 2021;31:26–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carrev.2020.12.002

8. Thoenes M, Bramlage P, Zamorano P et al. Patient screening for early detection of aortic stenosis (AS)-review of current practice and future perspectives. J Thorac Dis 2018;10:5584–94. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2018.09.02

9. Gaede L, Aarberge L, Brandon Bravo Bruinsma G et al. Heart valve disease awareness survey 2017: What did we achieve since 2015? Clin Res Cardiol 2019;108:61–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-018-1312-5

10. Wait S, Krishnaswamy P, Borregaard B et al. Heart valve disease: Working together to create a better patient journey. 2020. Available at: https://globalhearthub.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/HVD_report-final-2021.pdf [last accessed 05/05/2022].

11. Pibarot P, Lauck S, Morris T et al. Patient care journey for patients with heart valve disease. Can J Cardiol 2022;38:1296–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2022.02.025

12. Steeds RP, Potter A, Mangat N et al. Community-based aortic stenosis detection: clinical and echocardiographic screening during influenza vaccination. Open Heart 2021;8:e001640. https://doi.org/10.1136/openhrt-2021-001640

13. Evangelista A, Galuppo V, Mendez J et al. Hand-held cardiac ultrasound screening performed by family doctors with remote expert support interpretation. Heart 2016;102:376–82. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308421

14. Draper J, Subbiah S, Bailey R et al. Murmur clinic: validation of a new model for detecting heart valve disease. Heart 2019;105:56–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2018-313393

15. Ring L, Shah BN, Bhattacharyya S et al. Echocardiographic assessment of aortic stenosis: a practical guideline from the British Society of Echocardiography. Echo Res Pract 2021;8:G19–G59. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERP-20-0035

16. Robinson S, Rana B, Oxborough D et al. A practical guideline for performing a comprehensive transthoracic echocardiogram in adults: the British Society of Echocardiography minimum dataset. Echo Res Pract 2020;7:G59–G93. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERP-20-0026

17. Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2022;43:561–632. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395

18. Asteggiano R, Bramlage P, Richter DJ. European Society of Cardiology Council for Cardiology Practice worldwide survey of transcatheter aortic valve implantation beliefs and practices. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2018;25:608–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487318760029

19. Taniguchi T, Morimoto T, Takeji Y et al. Contemporary issues in severe aortic stenosis: Review of current and future strategies from the Contemporary Outcomes after Surgery and Medical Treatment in Patients with Severe Aortic Stenosis registry. Heart 2020;106:802–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2019-315672

20. Kang DH, Park SJ, Lee SA et al. Early surgery or conservative care for asymptomatic aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med 2020;382:111–19. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1912846

21. Chambers JB, Lancellotti P. Heart valve clinics, centers, and networks. Cardiol Clin 2020;38:65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccl.2019.09.006

22. Chambers JB, Prendergast B, Iung B et al. Standards defining a ‘Heart Valve Centre’: ESC Working Group on Valvular Heart Disease and European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery Viewpoint. Eur Heart J 2017;38:2177–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx370

23. Lancellotti P, Rosenhek R, Pibarot P et al. ESC Working Group on Valvular Heart Disease position paper–heart valve clinics: organization, structure, and experiences. Eur Heart J 2013;34:1597–606. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs443

24. Chambers JB. Specialist valve clinic: Why, who and how? Heart 2019;105:1913–20. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2019-315203

25. Zilberszac R, Lancellotti P, Gilon D et al. Role of a heart valve clinic programme in the management of patients with aortic stenosis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;18:138–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jew133

26. Lauck S, Forman J, Borregaard B et al. Facilitating transcatheter aortic valve implantation in the era of COVID-19: Recommendations for programmes. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2020;19:537–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474515120934057

27. Ionescu A, McKenzie C, Chambers JB. Are valve clinics a sound investment for the health service? A cost-effectiveness model and an automated tool for cost estimation. Open Heart 2015;2:e000275. https://doi.org/10.1136/openhrt-2015-000275

28. Haute Autorité Santé. Critères d’éligibilité des centres implantant des TAVIs. 2020. Available at: https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2020-11/rapport_tavis.pdf [last accessed 13/05/2022].

29. Nerla R, Prendergast BD, Castriota F. Optimal structure of TAVI heart centres in 2018. EuroIntervention 2018;14:AB11–AB8. https://doi.org/10.4244/EIJ-D-18-00656

30. Tarantini G, Nai Fovino L. Lifetime strategy of patients with aortic stenosis: The first cut is the deepest. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2021;14:1727–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2021.06.029