Training and development of cardiology trainees in the UK at a local level, is usually delivered through senior supervision by a consultant cardiologist. This training is overseen by clinical and educational supervisors, whose role is to set goals in line with existing training curricula. This is crucial to ensuring trainee development and attainment of skills in line with a pre-determined ‘gold standard’ for independent practice.

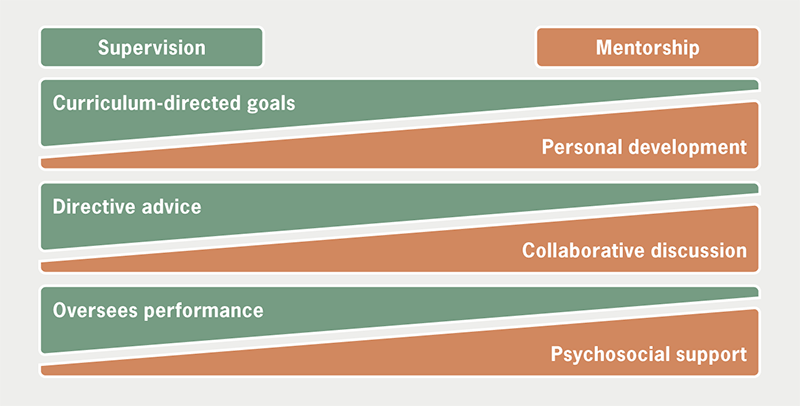

However, trainees may benefit from a separate relationship with a senior clinician, in which they can be nurtured outside of the auspices of a generic training curriculum. This describes mentorship: a bidirectional relationship between mentor and mentee offering personal development, independent growth, and exploration of interests, where a mentor can facilitate opportunities. The mentor’s role is multi-faceted, including that of coach, challenger, teacher and sounding board. Fundamentally, the relationship is grounded in mutual trust and support, commensurate to the needs of the mentee (figure 1).

Despite this, mentorship is not a guaranteed success, with potential for failure that can have far-reaching consequences for mentors and mentees alike. Moreover, in recent years, there has been a proliferation of novel modalities of mentorship. This can take the form of facilitated mentorship schemes, or shorter ‘speed-dating’ and ‘blind-date’ type mentorship schemes. It is not clear whether these fully facilitate the development of a positive relationship, expected of mentorship.

Here, we aim to discuss both the appealing and appalling aspects of mentorship within cardiology. We discuss the cornerstones of both successful and unsuccessful mentorship, and examine the structure and utility of novel methods of mentorship.

Mentorship: do we need it?

Mentorship is highly valued, even at pre-registrar level: 91% of pre-registrar doctors in the 2018 British Junior Cardiologists’ Association (BJCA) Starter National Training Survey indicated ‘role model advice’ as a key influencing factor for choosing a career in cardiology.1 The Shape of Training review has led to a significant change in the landscape of UK cardiology training,2 with mandatory dual accreditation in general medicine and cardiology necessitating commitments to general medicine throughout specialty training.3 As a result, achieving and maintaining cardiology-specific competencies has become more challenging. Appropriate mentorship may help trainees to navigate this challenge through development of key skills, which do not form part of a written curriculum. Mentees may draw inspiration from their mentors’ career paths and can build on mentors’ prior experience. Social support for mentees can augment self-confidence, and mentorship can help address concerns over balancing significant commitments, such as family life, with the demands of training. A recent American College of Cardiology (ACC) Early Career Leadership Council survey found a clear positive association between those who were satisfied with mentorship relationships, and satisfaction in achieving professional goals.4

The benefits of a productive mentor–mentee relationship are mutual: for mentors, it provides an opportunity to hone leadership and communication skills, reflect on their achievements, and explore their own transition from mentee to mentor. An effective partnership can result in collaborations from research and quality improvement perspectives, and over time, through exposure to each other’s networks and presentation platforms; such a relationship can foster further connections both within, and outside, the working environment. There is personal satisfaction derived from witnessing trainees flourish and gaining a valuable colleague who may be able to ‘give back’ to the system in which they were nurtured.

It, therefore, seems clear that effective mentorship brings benefits to mentors, mentees, and even the organisations that they work in. However, is all mentorship positive?

When mentor was found wanting: a tale from ancient Greece

The term ‘mentor’ traces its origins to Greek mythology: in The Odyssey, Odysseus entrusted his son, Telemachus, to a friend, Mentor, to act as a guide and teacher, when he departed from Ithaca to participate in the Trojan war. Unfortunately, Mentor lacked the traits to succeed in his role, leaving Telemachus insecure and lacking in confidence. It took the arrival of Athena, goddess of wisdom and war, appearing in the form of Mentor, to guide Telemachus and instil a sense of courage.5

Much like Mentor, individuals who have not developed the abilities to be an effective mentor in the modern day can create destructive relationships that harm trainees’ confidence and career interests. This can propel feelings of isolation and hopelessness.

Mentors often hold positions of authority, and may be simultaneously devoted to multiple clinical or academic projects. The intellectual, emotional, and time resources required for mentoring may be limited, challenging the notion of inherent altruism. The mentor–mentee relationship can even become a toxic manifestation of powerplay as time-strapped, deadline-driven mentors exploit their mentees, obliging them to complete work that does not align with the mentees’ needs. Disillusioned mentees are unlikely to collaborate harmoniously with them in the future, and may instead foster unhealthy competition and jealousy.

There may also be an unconscious tendency for a mentor to ‘imprint’ their values onto the mentee, and to mould their development to their own image. This may not be immediately evident to the mentee, or in some cases, may come across as stifling development. Having multiple mentor figures may help trainees escape this phenomenon, which the ACC Early Career Leadership Council survey have identified as a factor in improving mentee satisfaction.4

Extending the earlier metaphor, the tale of Mentor offers further cautionary lessons. First, Mentor was selected by Odysseus (father and supervisor); it is often desirable to separate the roles of mentor and supervisor, to enable independent growth of trainees in each domain. Furthermore, the absence of Odysseus in Telemachus’ early development highlights that the development of a mentor–mentee relationship should not come at the expense of other established supervisory relationships. In keeping with both points, the literature suggests that where there is potential conflict of interest between the roles of mentor and supervisor, they are less likely to be able to offer an objective view of a trainee’s performance, while also aiming to support reflection in self-assessment, thereby compromising both relationships.6,7

Mentees: not just followers

Although it may seem that mentees are somewhat passive followers of advice dispensed by mentors, a true mentor–mentee relationship must be active and bidirectional. This is a process that requires some agency and an element of reflective practice on the part of the mentee. Likewise, mentors may be able to offer practical advice, but it is up to mentees to process this advice in the context of their own needs.

An effective mentor–mentee relationship, therefore, also requires an appropriate mentee, who approaches the relationship with an active mindset, who is ready to be challenged and who has a desire to drive discussions to allow their own character to shine through, and be truly mentored, rather than led.

Was Mentor the only party at fault, or was Telemachus equally so as an unprepared mentee?

Mentorship: speed-dating, or in it for the long haul?

Although traditional mentorship is a foundational component of medical education and practice, the development of such relationships is contingent on a prospective mentee being well-acquainted with, or able to approach, an identified mentor figure. Such opportunities may not be equally available to all trainees. Furthermore, the rotational nature of training means that trainees often have a limited time to develop such relationships. In recent years, novel formats for increasing access to mentorship have emerged; the most common are ‘speed-dating’ mentoring, and formal mentoring schemes (table 1).

Table 1. Differing models of mentorship, their characteristics, strengths and weaknesses, and potential applications

| Traditional mentorship | Mentorship schemes | ‘Speed-dating’ mentorship | |

| Selection | Often mentee approaches mentor; occasionally recommended | Mentors and mentees sign up and are paired by a central organisation | |

| Duration of relationship | Variable; agreed by mentor and mentee | Minimum duration imposed by central body, often with option to extend | Short (single, e.g. 30–60-minute meeting), with option to pursue further |

| Setting | Variable; often relatively ad hoc and mutually determined | Schemes mostly mandate a set number of in-person or virtual meetings | Often organised as part of a wider medical event; mostly in-person (but some virtual) |

| Strengths |

|

|

|

| Weaknesses |

|

|

|

| The central imposition of a mentor/mentee is unable to reliably replicate central foundations of a successful long-term mentorship | |||

| Most suited for? | Variable; may extend from achieving discrete goals, to general career discussion and development | Achieving discrete short-term or mid-term career goals, networking | General career advice, networking |

‘Speed-dating’ mentoring refers to short mentoring sessions as part of a formally organised event (sometimes a session during a conference), where an organising body selects mentors (often eminent figures in the field) who devote a predetermined amount of time for predominantly career-development driven discussion with a mentee, who is not known to them beforehand. This is offered as a regular event at the European Society of Cardiology Congress, and at subspecialty society conferences, such as the European Heart Rhythm Association Congress, including both individual and group sessions.9,10

Mentoring schemes are also usually administered by a central body, who preselect mentors to match with trainees who are not known to them. In contrast to ‘speed-dating’ mentoring, engagement in formal mentoring schemes usually takes place over a longer period of time. Such mentorship arrangements may cover more than career development advice, with opportunities for clinical shadowing, improvement of personal well-being, and even academic collaboration during a sustained relationship. In recent years, several formal schemes have been initiated to promote mentorship within cardiology. The British Cardiovascular Society Women in Cardiology subsection and British Society for Heart Failure, both have active schemes,11,12 and other groups are actively developing schemes. We, in our former roles (AB, Secretary, PTT, Mentorship Officer, MD, President) on the British Junior Cardiologists’ Association Starter Committee, have recently completed a pilot edition of a mentorship scheme for prespecialty trainees interested in cardiology. Furthermore, these initiatives are not limited to cardiology: within the UK, the British Society of Gastroenterology, British Geriatric Society, and the Association of British Neurologists offer similar mentorship schemes.13–15

Both these formats are potentially valuable opportunities for prospective or current trainees to meet potential mentors, who they may not have otherwise had access to. Beyond broadening access, chance encounters with established figures outside of one’s scope of usual practice can lead to new perspectives on an individual’s development, and growth in new directions.

However, they are not without limitations, and these can be significant in nature. Most downsides to these initiatives result from the presence of an external body, and a ‘top-down’ approach to administering mentorship, leading to an artificial emulation of the prototypical mentor–mentee relationship.

The central body can become a ‘third wheel’ in the mentor–mentee relationship, imposing arbitrary targets that may not align with either mentor or mentee needs and expectations, ultimately stifling organic growth of the mentor–mentee relationship.

Much like Mentor and Telemachus, the mentor figure in these relationships is selected by an external party. The central imposition of a mentor figure means that mentor and mentee often enter relationships without a deep pre-existing understanding of their counterpart, with more time spent building a relationship from scratch than necessarily engaging in mentorship. This may be particularly problematic in the short-format ‘speed-dating’ form of mentorship, in which mentors may struggle to offer meaningful advice to a mentee that they have not observed prior to commencing mentorship. In addition, conflicting personalities may be inadvertently brought together, compromising a potential relationship.

Finally, as previously discussed, mentees often value having multiple mentors.4 Participation in a mentorship scheme, due to the demands that may be placed on mentees, may hinder their search for other mentor figures, and may generate a sense that their development is stifled as a result.

Beyond limitations for mentor and mentee, these novel initiatives carry ‘hidden costs’ for the organisations offering them. The administrative requirements of both, but in particular mentorship schemes, are high, and the relevant infrastructure must be in place to deliver them. There is also an inherent degree of risk involved as organisations recruit mentors and mentees who, in some cases, may not be suitable for their roles, despite stringent preselection.

It is likely that these initiatives are best placed to fulfil specific short- and mid-term goals, but may not routinely result in the long-term benefits that traditional mentorship offers. It is somewhat questionable as to whether short- and mid-term goal attainment, which is predominantly task and achievement focused, constitutes effective mentorship in its traditional sense, which at its core seeks to encourage growth without necessarily imposing targets.

All mentorships are equal, but some are more equal than others

A key update in the General Medical Council’s Good Medical Practice 2024 to ‘champion fair and inclusive leadership’ provides a stark reminder for cardiologists, whose profession suffers from gender and ethnic disparities.15 Female cardiology trainees, and those from non-UK medical schools, are more likely to experience inappropriate behaviour, which impacts retention and recruitment of staff, thus, hindering attempts to diversify the workforce and achieve inclusivity.16

A recent study found that female senior authors were significantly more likely to have female first authors in the same article, indicating a greater likelihood of gender-concordant mentorship in the academic arena.17 Similarly, a propensity towards ethnic concordance in mentoring relationships has been observed.4 Thus, while on the one hand, mentoring individuals from similar backgrounds has the potential to positively promote under-represented groups; excessive demographic uniformity in such relationships may in fact prevent workforce diversification by perpetuating existing imbalances. Creating ‘mentoring networks’ whereby mentees draw on experience from multiple mentors may help to mitigate this issue to some degree, and may be more effective in supporting long-term career outcomes.18

Conclusion

There is a need for mentorship within cardiology to help retain high-quality trainees and support academic endeavours. However, effective mentorship is not a simple relationship that can be entered on a whim, with many factors key to its success. At its core, mentorship is most appealing when mentor and mentee are positively engaged in a supportive environment. Novel methods of fostering mentorship relationships may broaden mentee access to mentors and fulfil specific needs, but their inherently artificial nature comes with pitfalls that render them an approximation of the prototypical ideal mentor–mentee relationship.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

References

1. Yazdani MF, Kotronias RA, Joshi A, Camm CF, Allen CJ. British cardiology training assessed: the British Junior Cardiologist’s Association (BJCA) starter member, national training survey results from 93 respondents in 2018 are presented. Eur Heart J 2019;40:2475–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz545

2. General Medical Council. Shape of training review. London: Shape of Training, 2013. Available from: https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/shape-of-training-final-report_pdf-53977887.pdf [accessed January 2024].

3. Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board. Curriculum for cardiology training. London: JRCPTB, 2022. Available from: https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/cardiology-2022-curriculum-final-v1_0_pdf-92049190.pdf

4. Abudayyeh I, Tandon A, Wittekind SG et al. Landscape of mentorship and its effects on success in cardiology. JACC Basic Transl Sci 2020;5:1181–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacbts.2020.09.014

5. Homer. The Odyssey. Translated by Robert Fagles. New York: Viking, 1996.

6. Mellon A, Murdoch-Eaton D. Supervisor or mentor: is there a difference? Implications for paediatric practice. Arch Dis Child 2015;100:873–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2014-306834

7. Garr RO, Dewe P. A qualitative study of mentoring and career progression among junior medical doctors. Int J Med Educ 2013;4:247–52. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5290.ba70

8. European Society of Cardiology. ESC Mentoring. Available at: https://www.escardio.org/The-ESC/ESC-Young-Community/ESC-Mentoring

9. European Society of Cardiology. Speed mentoring at EHRA 2023. Available at: https://www.escardio.org/Congresses-Events/EHRA-Congress/Scientific-sessions/speed-mentoring [accessed January 2024].

10. British Society of Heart Failure. Mentorship. Available at: https://www.bsh.org.uk/mentorship2023 [accessed January 2024].

11. Women in Cardiology. Cardiology trainee mentoring programme. Available at: https://www.womenincardiology.uk/news/cardiology-trainee-mentoring-programme [accessed January 2024].

12. British Society of Gastroenterology. BSG mentoring. Available at: https://www.bsg.org.uk/bsg-mentoring [accessed January 2024].

13. British Geriatrics Society. BGS mentoring guide. Available at: https://www.bgs.org.uk/mentor-questionnaire [accessed January 2024].

14. Association of British Neurologists. Mentoring. Available at: https://www.theabn.org/page/mentoring [accessed January 2024].

15. General Medical Council. Good medical practice 2024. London: GMC, 2023. Available from: https://www.gmc-uk.org/cy/professional-standards/good-medical-practice-2024

16. Camm CF, Joshi A, Eftekhari H et al. Joint British Societies’ position statement on bullying, harassment and discrimination in cardiology. Heart 2023;109:e1. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2023-322445

17. Asghar M, Usman MS, Aibani R et al. Sex differences in authorship of academic cardiology literature over the last 2 decades. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:681–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.05.047

18. Montgomery BL. Mapping a mentoring roadmap and developing a supportive network for strategic career advancement. SAGE Open 2017;7:2158244017710288. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017710288