Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) have been shown to reduce cardiovascular rehospitalisation in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) patients. However, it is unknown whether initiating SGLT2i during an inpatient stay for a HFrEF exacerbation results in better outcomes versus initiation post-discharge in a cohort of diabetic and non-diabetic patients. This study compares cardiovascular rehospitalisation, heart failure specific rehospitalisation, cardiovascular death, and all-cause death between patients initiated on SGLT2i as an inpatient versus post-discharge.

A retrospective study of four hospitals in England involving 184 patients with HFrEF exacerbations between March 2021 and June 2022 was performed. Cardiovascular rehospitalisation, heart failure specific rehospitalisation, cardiovascular death, and all-cause death were compared between the two groups using Cox regression. A Cox proportional-hazards model was fitted to determine predictors of cardiovascular rehospitalisation.

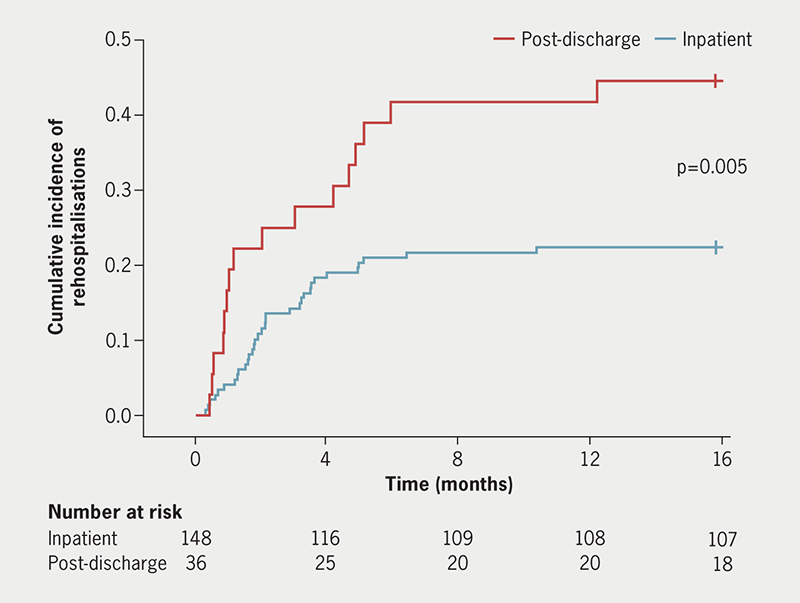

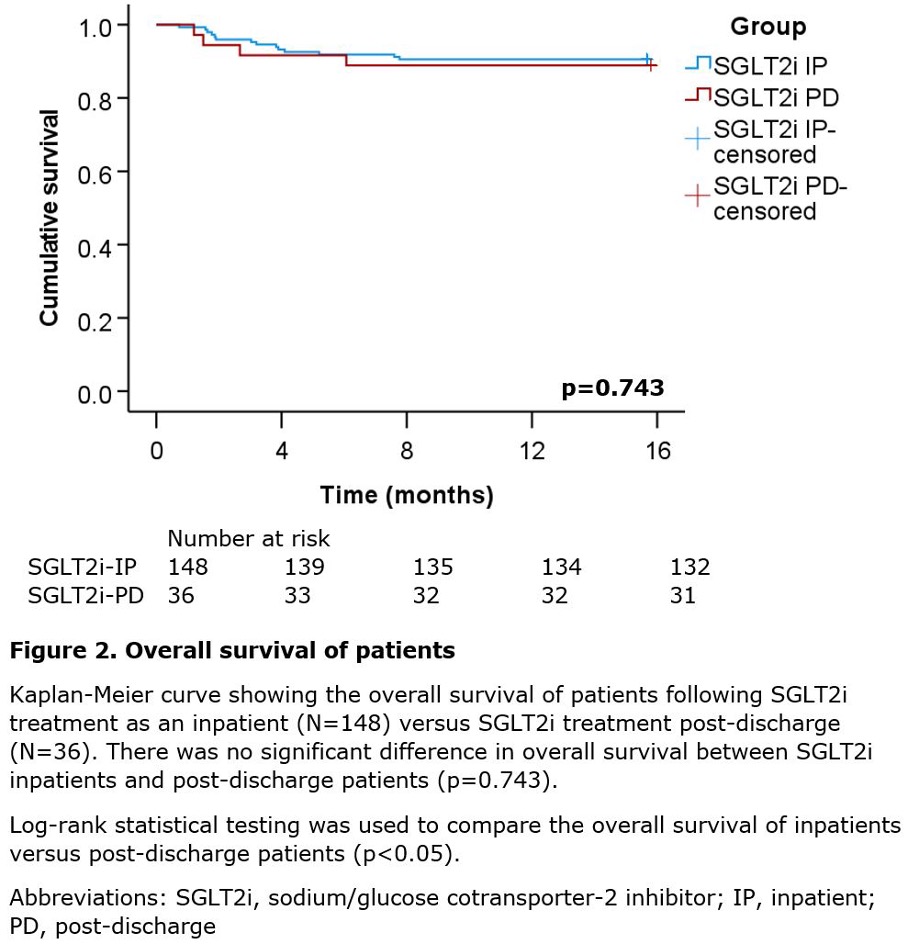

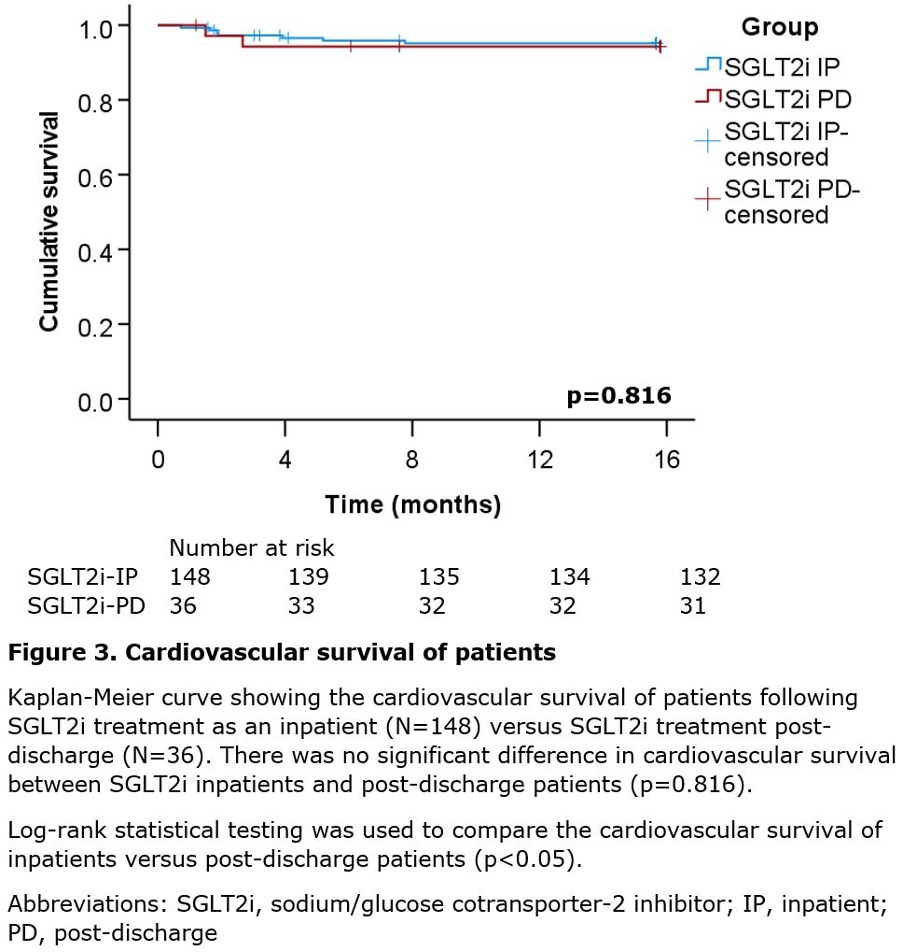

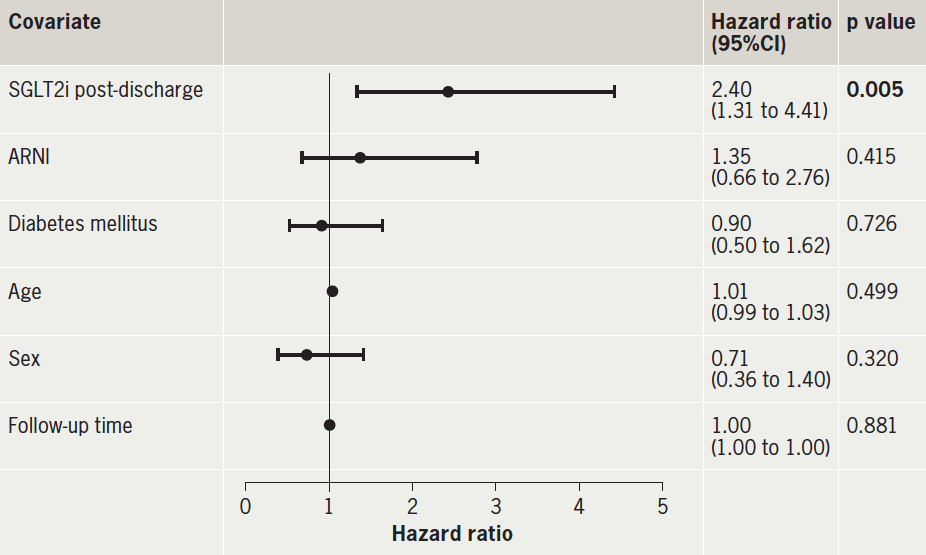

There were 148 (80.4%) individuals who received SGLT2i as an inpatient, while 36 (19.6%) individuals received SGLT2i post-discharge. Median follow-up was 6.5 months for inpatients and 7.5 months for post-discharge patients (p=0.522). SGLT2i inpatients had significantly reduced cardiovascular rehospitalisations (22.3%) versus post-discharge patients (44.4%) (p=0.005), and significantly reduced heart failure specific rehospitalisations (10.1%) versus post-discharge patients (27.8%) (p=0.018). There was no significant difference in all-cause death (p=0.743) and cardiovascular death (p=0.816) between the two groups. Initiating SGLT2i post-discharge was an independent predictor of cardiovascular rehospitalisation (hazard ratio 2.40, 95% confidence interval 1.31 to 4.41, p=0.005).

In conclusion, inpatient SGLT2i initiation for HFrEF exacerbations may reduce cardiovascular and heart failure specific rehospitalisation versus initiation post-discharge. In the absence of contraindications, clinicians should consider initiating SGLT2i once patients are clinically stable during inpatient HFrEF admissions.

Introduction

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) is a significant healthcare burden internationally, with an age-standardised prevalence of approximately 3.8% in women and 4.6% in men, and an estimated five-year mortality rate of 43%.1,2 Hospitalisations for heart failure exacerbations represent a major financial challenge to health services, and such patients have a higher risk of readmission and mortality.3

Previously, the DAPA-HF (Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction) trial demonstrated that dapagliflozin significantly reduces the risk of worsening heart failure and cardiovascular death.4 Similarly, the EMPULSE (Empagliflozin in Patients Hospitalised for Acute Heart Failure) trial demonstrated that empagliflozin is both safe and provides significant clinical benefit versus placebo.5 Dapagliflozin is a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor (SGLT2i); the cardioprotective benefits of SGLT2i are postulated to be due to their natriuretic effect, in addition to blood pressure reduction, sympathetic nervous system inhibition and improved cardiac energy metabolism.6–8

The 2021 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines recommend that SGLT2i should be commenced prior to discharge from an acute HFrEF exacerbation.9 However, it is currently unknown whether inpatient initiation of SGLT2i results in better outcomes versus initiation post-discharge in acute HFrEF in a cohort of diabetic and non-diabetic patients. Therefore, this study aims to compare cardiovascular rehospitalisation rates, heart failure specific rehospitalisation rates, cardiovascular death, and all-cause death between HFrEF patients commenced on SGLT2i as an inpatient versus post-discharge.

Materials and method

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

This multi-centre retrospective study involved 184 HFrEF patients over 18 years of age, with HFrEF defined as a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤40%. All patients presented with a New York Heart Association (NYHA) class between II and IV. Patients were admitted with an acute heart failure exacerbation between March 2021 and June 2022. The exclusion criteria included patients who were already taking an SGLT2i on admission, diagnosed with type 1 diabetes mellitus, symptomatic hypotension or had a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of <20 ml/min/1.73 m2.

Sample

This study involved four hospitals in the UK. There were 198 HFrEF patients screened, and 14 patients were excluded: 10 were already taking an SGLT2i on admission, one patient had symptomatic hypotension, one patient stopped SGLT2i upon hospital admission, one patient had a GFR <20 ml/min/1.73 m2 and there were no data available for one patient. Therefore, 184 patients were included in the final analysis.

Patients were divided into two groups: patients treated with SGLT2i as an inpatient (N=148) and patients treated with SGLT2i post-discharge (N=36). An inpatient was defined as commencing SGLT2i while in hospital for an acute HFrEF exacerbation, while post-discharge was defined as commencing SGLT2i after a hospital admission for an acute HFrEF exacerbation. All data were obtained from the National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (NICOR) Heart Failure Audit and electronic patient records, and fully anonymised.

Statistical analysis

The co-primary outcomes of this study were cardiovascular rehospitalisation and heart failure specific rehospitalisation. Secondary outcomes included cardiovascular death and all-cause death. Cardiovascular rehospitalisation was defined as an unplanned overnight hospital stay due to a cardiovascular reason.

Baseline demographic, clinical and laboratory parameters were compared between the two groups using the Mann-Whitney U test for non-parametric continuous variables. The chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables between the two groups, except where more than 20% of values were less than five patients, in which case the Fisher’s exact test was used. The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used to compare cardiovascular rehospitalisation, all-cause death and cardiovascular death between the two groups. Cox regression was performed to compare the cardiovascular rehospitalisation rate, heart failure specific rehospitalisation rate, all-cause death and cardiovascular death between the two groups. Furthermore, a Cox proportional-hazards regression model was fitted to determine predictors of cardiovascular rehospitalisation, in which patient group, angiotensin-receptor/neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) usage, diabetes mellitus, age, sex and follow-up time were covariates. The selection of these covariates was based on clinical significance. All statistical analyses were two-sided, with a significance value of p<0.05.

All statistical analyses were performed on IBM® SPSS® Statistics version 29 (International Business Machines Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design and conduct of this study.

Results

Baseline demographics

Overall, 184 patients were included in the study, of which 148 (80.4%) were given SGLT2i during their inpatient stay, while 36 (19.6%) were given SGLT2i post-discharge. There were 182 patients prescribed dapagliflozin, while two patients were prescribed empagliflozin. Of the SGLT2i post-discharge patients, 94.4% (34/36) received SGLT2i immediately post-discharge, i.e. the medication was added to the discharge summary to be commenced once out of hospital, while two patients received SGLT2i 132 days and 77 days post-discharge, respectively.

The median follow-up of SGLT2i inpatients was 6.5 months and SGLT2i post-discharge patients was 7.5 months (p=0.522). All dapagliflozin patients were prescribed 10 mg once daily, except one patient who was prescribed 5 mg once daily. The two empagliflozin patients were both prescribed 10 mg once daily.

There was no significant difference in the age of SGLT2i inpatients (mean 64.2 ± 14.4 years), and SGLT2i post-discharge patients (66.9 ± 12.4 years) (p=0.503). There was also no significant difference in the sex distribution between SGLT2i inpatients (74.3% male) and SGLT2i post-discharge patients (66.7% male) (p=0.354) (table 1).

Table 1. Baseline demographics, comorbidities and treatments

| SGLT2i inpatient (N=148, 80.4%) | SGLT2i post-discharge patient (N=36, 19.6%) |

p value | ||

| Mean age ± SD, years | 64.2 ± 14.4 | 66.9 ± 12.4 | 0.503 | |

| Male, n (%) | 110 (74.3%) | 24 (66.7%) | 0.354 | |

| Median follow-up (IQR), months | 6.5 (4.0–11.1) | 7.5 (5.0–10.9) | 0.522 | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White Mixed Asian/Asian British African/Caribbean Other Unknown |

65 (43.9%) 1 (0.7%) 32 (21.6%) 30 (20.3%) 19 (12.8%) 1 (0.7%) |

16 (44.4%) 0 (0.0%) 8 (22.2%) 6 (16.7%) 5 (13.9%) 1 (2.8%) |

0.848 | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| IHD Valve disease Congenital heart disease Hypertension DM CVA COPD Atrial fibrillation/flutter Cardiomyopathy |

39 (26.4%) 19 (12.8%) 1 (0.7%) 90 (60.8%) 67 (45.3%) 12 (8.1%) 11 (7.4%) 58 (39.2%) 39 (26.4%) |

11 (30.6%) 3 (8.3%) 0 (0.0%) 28 (77.8%) 19 (52.8%) 1 (2.8%) 3 (8.3%) 13 (36.1%) 9 (25.0%) |

0.611 0.455 1.000 0.057 0.418 0.263 0.739 0.734 0.868 |

|

| Smoking Current Ex |

11 (7.4%) 21 (14.2%) |

2 (5.6%) 6 (16.7%) |

0.875 | |

| Malignancy Previous Current Amyloid |

5 (3.4%) 9 (6.1%) 1 (0.7%) |

1 (2.8%) 2 (5.6%) 0 (0.0%) |

0.976 1.000 |

|

| Device therapy, n (%) | 0.253 | |||

| CRT-D CRT-P ICD PM |

9 (6.1%) 2 (1.4%) 17 (11.5%) 8 (5.4%) |

5 (13.9%) 1 (2.8%) 1 (2.8%) 1 (2.8%) |

||

| Medications, n (%) | ||||

| ACEi ARB Beta blocker Loop diuretic Thiazide diuretic MRA Aspirin Other antiplatelet Digoxin Statin Warfarin Other oral anticoagulant Amiodarone ISMN Ivabradine ARNI |

76 (51.4%) 24 (16.2%) 141 (95.3%) 132 (89.2%) 4 (2.7%) 117 (79.1%) 21 (14.2%) 16 (10.8%) 27 (18.2%) 60 (40.5%) 14 (9.5%) 65 (43.9%) 5 (3.4%) 7 (4.7%) 16 (10.8%) 37 (25.0%) |

20 (55.6%) 7 (19.4%) 32 (88.9%) 30 (83.3%) 1 (2.8%) 26 (72.2%) 8 (22.2%) 2 (5.6%) 4 (11.1%) 19 (52.8%) 3 (8.3%) 11 (30.6%) 2 (5.6%) 1 (2.8%) 2 (5.6%) 5 (13.9%) |

0.651 0.643 0.148 0.331 1.000 0.377 0.235 0.341 0.305 0.183 0.834 0.144 0.624 0.607 0.341 0.154 |

|

| Chi-squared, Fisher’s exact, and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare variables between SGLT2i inpatients versus post-discharge patients. Key: ACEi = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB = angiotensin-receptor blocker; ARNI = angiotensin-receptor/neprilysin inhibitor; CCB = calcium-channel blocker; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRT-D = cardiac resynchronisation therapy-defibrillator; CRT-P = cardiac resynchronisation therapy-pacemaker; CVA = cerebrovascular accident; DM = diabetes mellitus; ICD = implantable cardioverter defibrillator; IHD = ischaemic heart disease; IQR = interquartile range; ISMN = isosorbide mononitrate; MRA = mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; PM = pacemaker; SD = standard deviation; SGLT2i = sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor |

||||

The distribution of ethnicities and comorbidities were similar between the two groups (all p>0.05). There was also no significant difference in the proportion of patients on device therapies and all relevant cardiac medications (all p>0.05) (table 1).

The mean LVEF of SGLT2i inpatients (26.7%) and SGLT2i post-discharge patients (26.2%) were similar (p=0.749). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in the distribution of NYHA classes between SGLT2i inpatients and SGLT2i post-discharge patients (p=0.591). Laboratory parameters were not significantly different between SGLT2i inpatients and SGLT2i post-discharge patients (p>0.05), except for total cholesterol, in which SGLT2i post-discharge patients had significantly greater values (p=0.030) (table 2).

Table 2. Baseline clinical characteristics and laboratory values of study patients

| SGLT2i inpatient (N=148, 80.4%) | SGLT2i post-discharge patient (N=36, 19.6%) |

p value | |

| Clinical characteristics, mean (range) | |||

| Heart rate, bpm Systolic BP, mmHg LVEF, % <10, n (%) 10–19, n (%) 20–29, n (%) 30–40, n (%) Unknown, n (%) NYHA, n (%) Class II Class III Class IV Unknown |

75.7 (50–127) 114.2 (77–176) 26.7 (9–40) 1 (0.7%) 24 (16.2%) 58 (39.2%) 64 (43.2%) 1 (0.7%) 76 (51.4%) 25 (16.9%) 7 (4.7%) 40 (27.0%) |

78.9 (59–114) 117.7 (97–148) 26.2 (10–40) 0 (0.0%) 5 (13.9%) 15 (41.7%) 15 (41.7%) 1 (2.8%) 23 (63.9%) 5 (13.9%) 0 (0.0%) 8 (22.2%) |

0.246 0.085 0.653 0.591 |

| Laboratory parameter, mean (range) | |||

| Glucose, mmol/l HbA1c, mmol/mol Total cholesterol, mmol/l LDL-cholesterol, mmol/l HDL-cholesterol, mmol/l Triglyceride, mmol/l Urea, mmol/l Creatinine, mmol/l |

8.3 (3.8–25.7) 50.1 (18–144) 3.8 (1.5–8.5) 2.0 (0.6–5.6) 1.1 (0.3–2.5) 1.6 (0.4–7.6) 9.2 (3.2–25.2) 113.9 (55–207) |

8.0 (4.1–21.7) 56.9 (33–139) 4.3 (2.6–6.4) 2.2 (0.9–4.1) 1.3 (0.7–2.4) 1.9 (0.4–5.3) 8.3 (3.7–19.9) 108.7 (50–214) |

0.726 0.352 0.030 0.174 0.103 0.055 0.187 0.327 |

| Chi-squared, Fisher’s exact, and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare variables between SGLT2i inpatients versus post-discharge patients. Significant values are highlighted in bold. Key: BP = blood pressure; bpm = beats per minute; HbA1c = glycated haemoglobin; HDL = high-density lipoprotein; LDL = low-density lipoprotein; NYHA = New York Heart Association; SGLT2i = sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor |

|||

Survival analysis

Overall, the cardiovascular rehospitalisation rate was significantly lower in SGLT2i inpatients (33/148, 22.3%) versus SGLT2i post-discharge patients (16/36, 44.4%) (hazard ratio [HR] 2.30, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.27 to 4.19, p=0.006). Furthermore, the heart failure specific rehospitalisation rate was significantly lower in SGLT2i inpatients (15/148, 10.1%) versus SGLT2i post-discharge patients (10/36, 27.8%) (HR 2.71, 95%CI 1.19 to 6.19, p=0.018). However, there were no significant differences in cardiovascular death (HR 1.20, 95%CI 0.25 to 5.80, p=0.817) and all-cause death (HR 1.20, 95%CI 0.40 to 3.66, p=0.744) between the two groups (table 3).

Table 3. Clinical end points

| Clinical end point, n (%) | SGLT2i inpatient (N=148, 80.4%) |

SGLT2i post-discharge patient (N=36, 19.6%) |

Hazard ratio (95%CI) | p value |

| Cardiovascular rehospitalisations | 33 (22.3%) | 16 (44.4%) | 2.30 (1.27 to 4.19) | 0.006 |

| Heart failure specific rehospitalisations | 15 (10.1%) | 10 (27.8%) | 2.71 (1.19 to 6.19) | 0.018 |

| Cardiovascular death | 8 (5.4%) | 2 (5.6%) | 1.20 (0.25 to 5.80) | 0.817 |

| All-cause death | 14 (9.5%) | 4 (11.1%) | 1.20 (0.40 to 3.66) | 0.744 |

| Cox regression was used to compare outcomes between SGLT2i inpatients versus post-discharge patients. Significant values are highlighted in bold. Key: CI = confidence interval; SGLT2i = sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor |

||||

The log-rank test also demonstrated that cardiovascular rehospitalisation was significantly reduced in SGLT2i inpatients versus SGLT2i post-discharge patients (log-rank p=0.005, figure 1). In the SGLT2i inpatient group, causes of cardiovascular rehospitalisation included: 45.5% (15/33) from heart failure exacerbation, 9.1% (3/33) from cardiogenic shock, 9.1% (3/33) from stroke, 6.1% (2/33) from cardiogenic syncope, 6.1% (2/33) from non-ST elevation myocardial infarction, 6.1% (2/33) from cardiac arrest, 3.0% (1/33) from ventricular bigeminy, 3.0% (1/33) from palpitations, 3.0% (1/33) from atrial fibrillation, 3.0% (1/33) from aortic stenosis, and 3.0% (1/33) from sepsis. The cause of rehospitalisation of one patient in this group was unknown. In the SGLT2i post-discharge patients, causes of cardiovascular rehospitalisation included: 62.5% (10/16) from heart failure exacerbation, 6.25% (1/16) from anaemia, 6.25% (1/16) from ischaemic heart disease, 6.25% (1/16) from multi-vessel coronary disease, 6.25% (1/16) from aortic stenosis, 6.25% (1/16) from unstable angina and 6.25% (1/16) from abdominal aortic aneurysm.

| Log-rank statistical testing was used to compare the proportion of patients avoiding cardiovascular rehospitalisation between inpatients and post-discharge patients (p<0.05). |

There was no significant difference in all-cause death (log-rank p=0.743, figure 2) and cardiovascular death (log-rank p=0.816, figure 3) between SGLT2i inpatients versus SGLT2i post-discharge patients. Overall, 55.6% (10/18) of deaths were cardiac related: seven from heart failure exacerbation, one from pulmonary oedema, one from multi-organ failure secondary to heart failure, and one from cardiac arrest. A further 11.1% (2/18) of deaths were non-cardiac and included one case of sepsis and community-acquired pneumonia, and another case of biliary sepsis. The cause of death for 33.3% (6/18) of patients was unknown.

A Cox proportional-hazards regression model was fitted to determine predictors of cardiovascular rehospitalisation. Receiving SGLT2i post-discharge was an independent predictor of cardiovascular rehospitalisation; these patients had a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular rehospitalisation (HR 2.40, 95%CI 1.31 to 4.41, p=0.005) versus SGLT2i inpatients. ARNI usage, diabetes mellitus, age, sex and follow-up time were not significant predictors of cardiovascular rehospitalisation (all p>0.05) (table 4).

| Significant values are highlighted in bold. Key: ARNI = angiotensin-receptor/neprilysin inhibitor; CI = confidence interval; SGLT2i = sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor |

Discussion

Previously, the STRONG-HF (Safety, Tolerability, and Efficacy of Rapid Optimization, Helped by NT-proBNP Testing, of Heart Failure Therapies) trial has demonstrated that rapid up-titration of guideline-directed medical therapy significantly reduces heart failure readmission and all-cause death in HFrEF patients versus usual care. However, the STRONG-HF trial was conducted prior to the advent of SGLT2i.10 Furthermore, the DAPA-HF trial has demonstrated that dapagliflozin significantly reduces cardiovascular rehospitalisation and cardiovascular death in HFrEF patients.4 However, it is currently unknown whether initiating SGLT2i during an inpatient stay for an acute HFrEF exacerbation results in better outcomes versus initiating SGLT2i post-discharge in a cohort of both diabetic and non-diabetic patients. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to compare cardiovascular rehospitalisation, heart failure specific rehospitalisation, cardiovascular death, and all-cause death between HFrEF patients treated with SGLT2i as an inpatient versus post-discharge in a cohort of both diabetic and non-diabetic patients.

The salient findings of this study are as follows. First, initiating SGLT2i during an inpatient stay for an acute HFrEF exacerbation significantly lowers cardiovascular rehospitalisation rates versus initiating SGLT2i post-discharge (p=0.006, table 3). Second, initiating SGLT2i during an inpatient stay for an acute HFrEF exacerbation significantly lowers heart failure specific rehospitalisation rates versus initiating SGLT2i post-discharge (p=0.018, table 3). Third, there is no significant difference in all-cause death between SGLT2i inpatients and post-discharge patients (p=0.743, figure 2). Fourth, there is no significant difference in cardiovascular death between SGLT2i inpatients and post-discharge patients (p=0.816, figure 3).

Previously, the Sotagliflozin in Patients with Diabetes and Recent Worsening Heart Failure (SOLOIST-WHF) trial demonstrated that irrespective of inpatient or post-discharge initiation of sotagliflozin, there was a significant reduction in the composite primary outcome of cardiovascular death, cardiovascular rehospitalisation and urgent visits due to HFrEF, versus placebo. The authors concluded that SGLT2i should be initiated in type 2 diabetic patients with worsening heart failure as soon as the patient is clinically stable, and preferably prior to discharge.11 This study builds on the SOLOIST-WHF trial by demonstrating that this benefit extends to non-diabetic patients, and also showing that a further benefit is achieved by starting SGLT2i as an inpatient versus post-discharge. Furthermore, this study gives support to the 2021 ESC guidelines, which recommend that evidence-based oral medical treatment, including SGLT2i, should be initiated before discharge.9

A potential explanation for the reduced cardiovascular and heart failure specific rehospitalisation rates in SGLT2i inpatients versus post-discharge patients may be due to synergism between SGLT2i and furosemide. Both drugs act within the nephron: while furosemide inhibits sodium and, hence, water reabsorption in the ascending loop of Henle through binding to the sodium-potassium-chloride cotransporter, SGLT2i inhibits SGLT2 transporters in the proximal convoluted tubule to prevent sodium, glucose and, therefore, water reabsorption.8,12 Furthermore, Ibrahim et al., reported significantly greater urine output and diuretic response, with no significant adverse impact on renal function, in patients managed with SGLT2i and furosemide combination therapy versus furosemide monotherapy (p<0.001).13 Therefore, administering SGLT2i and furosemide in combination during an inpatient stay when the patient is most acutely fluid overloaded may result in better outcomes and, hence, reduce rehospitalisation risk versus treatment post-discharge. Reducing rehospitalisation rates due to HFrEF is vital, because it may reduce the financial burden on the healthcare system and improve patient prognosis.14,15

The results of this study should be interpreted in the context of some limitations. It was a retrospective study, with a relatively small sample size. Since only four hospitals were studied, this potentially limits the study’s generalisability. Future studies should consider using the broader NICOR Heart Failure Audit database to increase generalisability. There was a discrepancy in the size of the inpatient and the post-discharge groups. Furthermore, the length of follow-up may have been too short to determine the true difference in all-cause death and cardiovascular death between the two groups. However, this was unavoidable, given that the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) only recommended dapagliflozin for HFrEF since late February 2021, and empagliflozin was only recommended for HFrEF since March 2022.16,17 It is also important to acknowledge the inherent limitations of utilising registry data, such as the potential variability in quality of collected data, and that the researchers did not collect the original data themselves. Future studies should, thus, incorporate a longer follow-up to determine whether all-cause death and cardiovascular death are truly different between SGLT2i inpatients and post-discharge patients. A randomised-controlled prospective study would also build on this study’s findings and increase the level of evidence.

The recent PRESERVED-HF (Effects of Dapagliflozin on Biomarkers, Symptoms and Functional Status in Patients With Preserved Ejection Fraction Heart Failure) trial has also suggested that SGLT2i may improve symptoms and physical limitations among heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) patients.18 Therefore, it would be interesting to compare outcomes between SGLT2i inpatients and post-discharge patients with HFpEF in a similar fashion to this study.

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated that initiating SGLT2i during an inpatient stay for an acute exacerbation of HFrEF may significantly lower cardiovascular and heart failure specific rehospitalisation rates versus initiating SGLT2i post-discharge. Therefore, in the absence of a contraindication, clinicians should consider initiating SGLT2i once the patient is clinically stable during an inpatient admission of HFrEF, irrespective of whether the patient has type 2 diabetes.

Key messages

- Previous studies have shown that sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) reduce cardiovascular rehospitalisation and death in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) patients

- However, it is unknown whether initiating a SGLT2i as an inpatient for a HFrEF exacerbation improves outcomes versus initiation post-discharge in a cohort of diabetic and non-diabetic patients

- This study demonstrated that initiating a SGLT2i for inpatients with a HFrEF exacerbation resulted in significantly lower cardiovascular and heart failure specific rehospitalisation rates versus initiation post-discharge

- In the absence of contraindications, clinicians should consider initiating a SGLT2i as soon as the patient is clinically stable during an inpatient admission for HFrEF, irrespective of whether the patient has type 2 diabetes

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Study approval

This study was a retrospective analysis of registry data for the purposes of quality assurance, therefore the need for formal ethical approval was waived by our institution (Queen Mary, University of London). All data were fully anonymised.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, we would like to thank Dr Shanti Velmurugan for overseeing this project. We would also like to thank all the heart failure staff across all disciplines in Barts Health NHS Trust. Finally, we want to extend our gratitude to Mr Patrick Moran from the Barts Health NHS Trust heart failure audit team.

Editors’ note

Figures 2 and 3 are available in the online version of this article.

References

1. Tiller D, Russ M, Greiser KH et al. Prevalence of symptomatic heart failure with reduced and with normal ejection fraction in an elderly general population – the CARLA study. PLoS One 2013;8:e59225. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0059225

2. Groenewegen A, Rutten FH, Mosterd A, Hoes AW. Epidemiology of heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2020;22:1342–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.1858

3. Agarwal MA, Fonarow GC, Ziaeian B. National trends in heart failure hospitalizations and readmissions from 2010 to 2017. JAMA Cardiol 2021;6:952. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2020.7472

4. McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1995–2008. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1911303

5. Voors AA, Angermann CE, Teerlink JR et al. The SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure: a multinational randomized trial. Nat Med 2022;28:568–74. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01659-1

6. Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Zannad F. Effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors for the treatment of patients with heart failure: proposal of a novel mechanism of action. JAMA Cardiol 2017;2:1025. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2017.2275

7. Lytvyn Y, Bjornstad P, Udell JA, Lovshin JA, Cherney DZI. Sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibition in heart failure: potential mechanisms, clinical applications, and summary of clinical trials. Circulation 2017;136:1643–58. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030012

8. Lopaschuk GD, Verma S. Mechanisms of cardiovascular benefits of sodium glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors. JACC Basic Transl Sci 2020;5:632–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacbts.2020.02.004

9. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M et al. 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021;42:3599–726. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368

10. Mebazaa A, Davison B, Chioncel O et al. Safety, tolerability and efficacy of up-titration of guideline-directed medical therapies for acute heart failure (STRONG-HF): a multinational, open-label, randomised, trial. Lancet 2022;400:1938–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02076-1

11. Bhatt DL, Szarek M, Steg PG et al. Sotagliflozin in patients with diabetes and recent worsening heart failure. N Engl J Med 2021;384:117–28. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2030183

12. Huxel C, Raja A, Ollivierre-Lawrence MD. Loop diuretics. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing, 2022. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546656/ [accessed 28 July 2022].

13. Ibrahim A, Ghaleb R, Mansour H et al. Safety and efficacy of adding dapagliflozin to furosemide in type 2 diabetic patients with decompensated heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. Front Cardiovasc Med 2020;7:602251. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2020.602251

14. Kwok CS, Abramov D, Parwani P et al. Cost of inpatient heart failure care and 30-day readmissions in the United States. Int J Cardiol 2021;329:115–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.12.020

15. Shahar E, Lee S, Kim J, Duval S, Barber C, Luepker RV. Hospitalized heart failure: rates and long-term mortality. J Cardiac Fail 2004;10:374–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2004.02.003

16. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Dapagliflozin for treating chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. London: NICE, 2021. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta679

17. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Empagliflozin for treating chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction – recommendations. London: NICE, 2022. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta679/chapter/1-Recommendations

18. Nassif ME, Windsor SL, Borlaug BA et al. The SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a multicenter randomized trial. Nat Med 2021;27:1954–60. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01536-x