A quiet revolution without fanfare took place at a meeting, witnessed by over 1,000 people both in London and live streamed across the globe on 31 January 2024. It was unprecedented, going against received wisdom. That, it was possible to treat atherosclerotic coronary artery disease with an updated Andreas Grüntzig’s balloon alone, without the safety net and comfort of implanting a single stent. Three interactive cases were treated with the drug-coated balloon and all patients were same-day discharged. Seemingly a show of simplicity, parsimony and bravado, but dive a little deeper, the skill set for stent-free coronary intervention has been meticulously studied over the last 20 years by pioneers and early adopters alike. The sacred cow slayed on this historic day was that balloon-inflicted coronary dissection rarely leads to occlusion, having effective antiplatelet therapy on board. And, potentially occlusive dissection is, not only predictable, but this method can be used in the ambulatory care setting. Thus, saving hospital bed stays. This event will be remembered as the tipping point at which a paradigm shift has occurred, but going back to embracing Grüntzig’s lessons. This is timely too, considering that two decades of systematic stenting has led to stent failures comprising nearly a third of daily interventional workload.

Disease made worse?

When Grüntzig extended balloon angioplasty from the leg to the heart as a minimally invasive procedure for coronary atherosclerosis in 1977, there was a 10% rate of abrupt vessel closure (AVC), possibly causing a myocardial infarction (MI).1,2 At the time, cardiac surgeons stood by, rescuing these patients with emergency coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Bare-metal stent (BMS), a balloon-expandable metallic-mesh scaffold was introduced 10 years later to overcome this immediate complication. The drug-eluting stent (DES), marketed from 2003, overcomes BMS’s in-stent restenosis (ISR) due to healing tissue proliferation enveloping the stent struts, re-occluding the vessel lumen within three months in susceptible patients. DES has an antiproliferative drug embedded within its polymer-covered stent struts, which elutes over months to the surrounding tissue, hence, preventing uncontrolled cell growth and ISR. Unfortunately, ISR is merely delayed by this strategy, and stent thrombosis becomes prevalent with its widespread use. A recently reported 15-year follow-up study of this first-generation DES found a 20% mortality every five years, suggesting that coronary artery disease has a malignant course.3 In addition, there was 37% stent failure, with half resulting in an MI, and that this continues indefinitely. Despite this, the interventional cardiology community takes it for granted that stenting defines percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), to overcome recoil, avoid AVC and prevent ISR. New iterations of DES appear every few years, but in real-world practice, stent failure remains a problem contributing to up to a third of daily interventional caseload.2 The high stent failure rate can partly be explained by the increasingly complex PCI undertaken, at bifurcation and with calcium modification, and longer stents implanted for more complete plaque coverage, instantly normalising the lumen of the diseased coronary artery.4 Perhaps use of intravascular imaging (IVI), such as ultrasound (IVUS) or optical coherence tomography (OCT), would abolish stent failure due to technical errors. However, the philosophy of equating stent failure with skilled incompetence is being challenged by an idea taking root at the fringe.

History remake

The Advanced Cardiovascular Intervention (ACI) 2024 meeting organised by the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS) that took place in London between 31 January and 2 February, has for the first time devoted a full session on day one, between 1.00 pm and 3.50 pm, with five short talks on the drug-coated balloon (DCB) with demonstrations in Grüntzig’s style of didactic teaching. Three cases were interactively broadcast from Norwich and Norfolk University Hospital, East Anglia, to over 1,000 participants, both onsite in the Richmond Suite at the Hilton London Metropole Hotel on Edgware Road, and online to 45 countries. One elderly patient needed rotational atherectomy to the calcific left anterior descending (LAD) artery followed by balloon pre-dilations. There was some balloon constraint suggesting underexpansion in the prepared vessel, but the resulting lumen was greater than 70% angiographically by visual estimate. Next, a DCB was applied. The DCB is a vehicle to transfer an antiproliferative drug directly to the vessel wall. The other two patients too had similar results with some haziness within the treated segments. The DCB PCI safety triad was drummed into the audience:

- Adequate luminal gain.

- Unimpeded flow.

- No dye hold-up.

The operators quipped that, “perfection is the enemy of good”. A panellist asked the same question during each case, “is this patient going home today?”. The answers were consistently, “yes”, but clearly this was no standard practice, without a stent in place. These cases were performed outside guidelines, with neither IVI, nor with intracoronary physiology perking the audience’s scepticism, who were used to elaborate PCI performed at meetings, where use of these adjunctive tools are non-negotiable. These DCB cases were short, pragmatic and uneventful, devoid of any drama, that was why three cases were squeezed in, instead of the usual two, but each adhered closely to the DCB consensus statement.5 On the other hand, stenting gives a sense of comforting safety to the PCI operator. And acute or early stent thrombosis within 30 days of 0.8% is an accepted complication consented for; in 50% of cases, it is because, “the patient missed the pills”.2,6 Whereas AVC after DCB is over 10 times less common than stent thrombosis, irrespective of case complexity.7

Less is more

The above event was akin to an epochal shift as significant as a continental drift. Turning normal practices on their heads, causing discontent in some of the audience. However, the overall demonstration was calculated and no recklessness was involved when it came to patient safety. It was a journey that was started with Bruno Scheller in parallel to the first-generation DES’s development in the early 2000s. Scheller did the basic research into balloon coating of an antiproliferative drug, paclitaxel with iopromide contrast media as an excipient. This allows delivery of paclitaxel to the balloon-injured vessel wall to inhibit tissue proliferation that causes restenosis, in the absence of immediate elastic recoil, done in the leg first, as Grüntzig did.8 Scheller later partnered with Franz Kleber and other German interventionalists in applying his DCB to the coronary artery.9 Simon Eccleshall saw the promise of the practice and promoted the idea over the last 10 years in the UK with B. Braun’s support, the German DCB manufacturer based in Melsungen, as medical industry collaboration. It was not a smooth ride befitting a Hollywood script, as it took unyielding conviction to go against the grain. Grüntzig was heavily criticised by seniors for his 10% AVC, one reason why he left Zurich for Atlanta in 1980. This is how some therapeutic advances are made, by challenging the status quo. There are multiple randomised-controlled trials (RCT) attesting to DCB’s efficacy in small vessel coronary artery disease, high-risk bleeder and ISR, and large all-comers’ registries with long-term follow-up.5 In comparison to the stent, DCB failure appears to be about 5% and plateaus after three years.10 And it is associated with late luminal gain and preserved endothelial function.5 In vascular interventional practice, literally and metaphorically, the heart goes where the leg leads; DCB use is now supported by a solid evidence-base for peripheral artery disease with class IA recommendation for de novo disease.

The good tear

Since Grüntzig’s days, coronary intervention advances by small steps, extrapolating current knowledge to wider practices by early adopters, then proving any new technique or indication in RCTs to convince the masses. This journey takes between 20 and 25 years, for example the adoption of the radial access by Ferdinand Kiemeneij, or bifurcation crush stenting by Antonio Colombo. The latter PCI maestro is now advocating DCB in the LAD.11 Kleber over the years posed this question to his listeners, “if after ballooning a diseased coronary artery, the result is a stent-like lumen, what then is the purpose of implanting a stent, if it will fail anyway in time?”. Grüntzig’s first LAD balloon angioplasty was effective for 23 years. This seminal day demonstrated that AVC is caused by thrombosis, which has been banished by pre-treatment with dual antiplatelet drugs, and not by recoil or dissection, as is generally feared by PCI operators. This is synonymous with the first heart transplantation in 1967 that failed within 18 days.12 With the use of better antirejection drugs in the early 1980s, the practice was revived. Conversely, AVC is more common with distal stent edge dissection, where the resulting flap is counterflow.2 This can appear angiographically as dye hold-up.

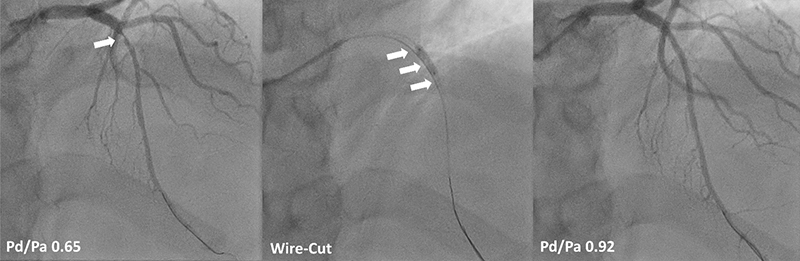

Large-vessel DCB versus DES RCTs are on the way, but expectation needs to be tempered with the lessons learnt from the radial approach, that is, the over 70% high-volume radial operators were the ones who proved its mortality benefits in acute coronary syndrome. In other words, as with any procedural treatment modalities, there is a significant performance bias that needs to be taken into account. Further, IVI-guided stenting has become the new ideal, even if the incremental gain in stent failure reduction is salutary. For example, it takes 115 OCTs, or about £80,000, to prevent one stent thrombosis in two years.13 The corollary to this is, no stent, no stent thrombosis. Figure 1 illustrates a safe start for de novo DCB angioplasty adopters with controlled plaque dissection,14 and intracoronary pressure measurement as surrogate for flow.15 This is a modern adaptation of Grüntzig’s timeless teachings. Afterall, an omelette cannot be made without breaking eggs, neither can a diseased coronary artery be stretched without dissecting it; at least this is done knowing that the patient will be safe, as publicly shown in the pivotal meeting in London on 31 January 2024.

Conclusion

Systematic stent use in PCI is not necessary to avoid AVC or coronary restenosis. The former is mostly thrombotic and the latter can be prevented by DCB. Importantly, stenting aims for technical excellence with acute maximal luminal gain. While DCB minimises the procedure with an acceptable result. Thus, the so-called, ‘ugly-duckling phenomenon’, when biology takes over with pulsatile flow unimpeded and the whole artery dilates in calibre over time, with preservation of vascular endothelial function, which is impaired by the stent. Nevertheless, complementary use of DCB and DES has become the new normal in de novo coronary intervention.

Key messages

- Stent-free coronary angioplasty with drug-coated balloon has entered mainstream practice

- Balloon-inflicted coronary dissection causing abrupt vessel closure is predictable and is very rare with dual antiplatelet drug therapy

- Drug-coated balloon prevents restenosis, without the attendant risk of stent thrombosis, and is the preferred strategy for the high-risk bleeder, those with vasculitic or thrombotic tendency, where drug compliance is an issue, or any patient who requires an urgent non-cardiac surgery

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Patient consent

The patient has kindly given his informed consent for his case to be shared for learned communication.

Acknowledgements

The author expresses gratitude to Drs Rajan Sharma and Manav Sohal for their insightful leadership; cardiac catheter laboratory seniors, Mary Keal and Menene Endaya (nursing), Dinesh Sajnani and Jaysson Crusis (radiology), and Andreia Alves (physiology); Dr EnHui Yong who assisted in the case described in figure 1 and the patient who consented for his procedure to be used as an illustration; the staff of Belgrave ward who looked after him; Fatima Cassinda-Macedo who is ever so helpful in patient coordination and Farida Ismail who reliably keeps stock of PCI equipment.

References

1. Gruntzig A. Transluminal dilatation of coronary-artery stenosis. Lancet 1978;1:263. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(78)90500-7

2. Lim PO. Stent, balloon and hybrid in de novo PCI: could the whole be greater than the sum of its parts? Br J Cardiol 2023;30:149. https://doi.org/10.5837/bjc.2023.037

3. Nishiura N, Kubo S, Fujii C et al. Fifteen-year clinical outcomes after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. Circ J 2024;88:938–43. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-23-0929

4. Kong MG, Han JK, Kang JH et al. Clinical outcomes of long stenting in the drug-eluting stent era: patient-level pooled analysis from the GRAND-DES registry. EuroIntervention 2021;16:1318–25. https://doi.org/10.4244/EIJ-D-19-00296

5. Jeger RV, Eccleshall S, Wan Ahmad WA et al. Drug-coated balloons for coronary artery disease: third report of the International DCB Consensus Group. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2020;13:1391–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2020.02.043

6. Claessen BE, Henriques JP, Jaffer FA et al. Stent thrombosis: a clinical perspective. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2014;7:1081–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2014.05.016

7. Funatsu A, Sato T, Koike J et al. Comprehensive clinical outcomes of drug-coated balloon treatment for coronary artery disease. Insights from a single-center experience. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2024;103:404–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccd.30945

8. Tepe G, Zeller T, Albrecht T et al. Local delivery of paclitaxel to inhibit restenosis during angioplasty of the leg. N Engl J Med 2008;358:689–99. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0706356

9. Kleber FX, Mathey DG, Rittger H et al. How to use the drug-eluting balloon: recommendations by the German consensus group. EuroIntervention 2011;7(suppl K):K125–K128. https://doi.org/10.4244/EIJV7SKA21

10. Venetsanos D, Omerovic E, Sarno G et al. Long term outcome after treatment of de novo coronary artery lesions using three different drug coated balloons. Int J Cardiol 2021;325:30–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.09.054

11. Gitto M, Sticchi A, Chiarito M et al. Drug-coated balloon angioplasty for de novo lesions on the left anterior descending artery. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2023;16:e013232. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.123.013232

12. Sliwa K, Zilla P. 50th anniversary of the first human heart transplant – how is it seen today? Eur Heart J 2017;38:3402–04. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx695

13. Ali ZA, Landmesser U, Maehara A et al. Optical coherence tomography-guided versus angiography-guided PCI. N Engl J Med 2023;389:1466–76. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2305861

14. Lim PO. Underexpanded stent and force-focused double buddy-wire. Korean Circ J 2023;53:722–5. https://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2023.0173

15. Shin ES, Ann SH, Balbir Singh G et al. Fractional flow reserve-guided paclitaxel-coated balloon treatment for de novo coronary lesions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2016;88:193–200. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccd.26257