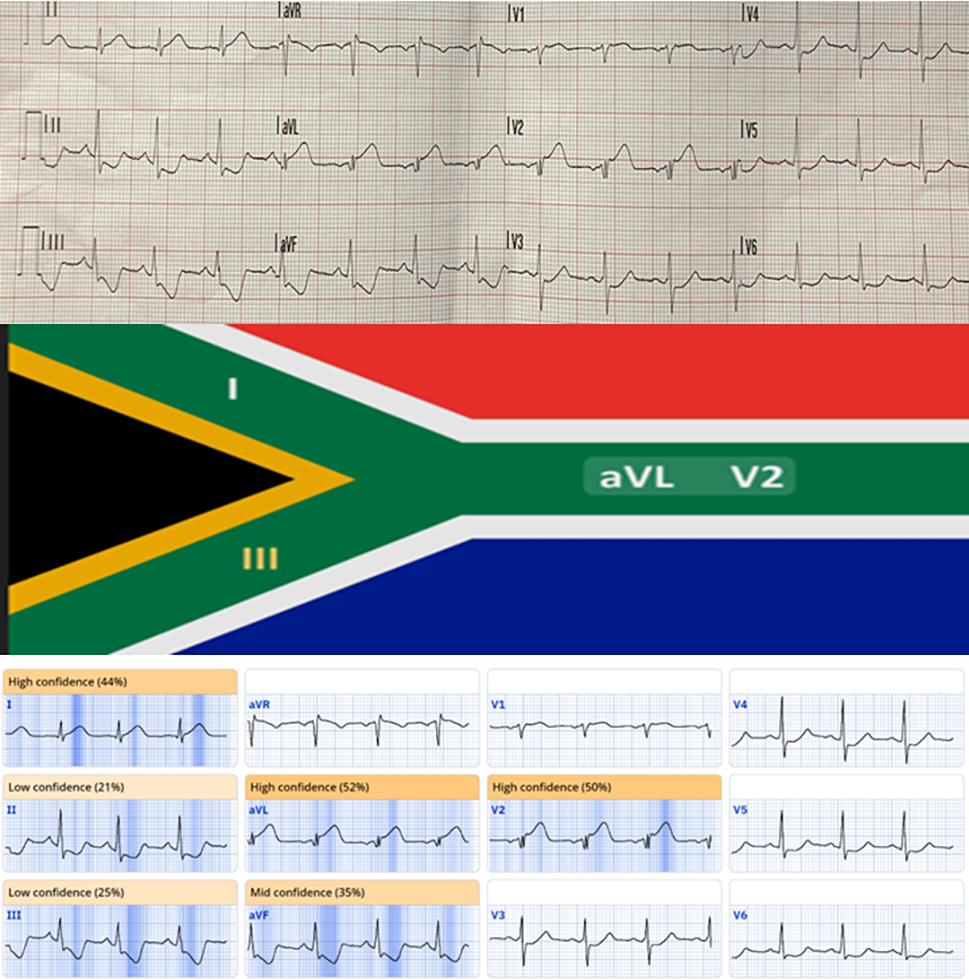

A 44-year-old man presented with chest pain and an unusual pattern of ST-elevation in leads aVL and V2, and ST-depression in leads II, III and aVF on electrocardiogram (ECG). Artificial intelligence (AI)-augmented ECG interpretation reported the abnormality as indicative of occlusive myocardial infarction (OMI) and highlighted the abnormal leads in the pattern that was recognised to be that of the South African flag. This previously reported pattern is associated with acute occlusion of the intermediate or high diagonal coronary arteries, which was then confirmed on coronary angiography, but only when an extreme left anterior oblique (LAO) caudal view was used. The intermediate artery was successfully treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). It is our experience, like that of Louis Pasteur, that chance appears to favour the prepared mind. This case highlights the importance of being prepared by recognising non-typical ECG patterns associated with acute coronary occlusion, and being aware of which vessel is likely to be occluded. This demonstrates the utility that AI-augmented ECG interpretation can bring to cardiologists to refine patient management.

Introduction

Acute coronary occlusions involving the diagonal or intermediate branches present diagnostic challenges, since classical patterns of ST-elevation in contiguous leads on electrocardiogram (ECG) are often not apparent. This leads to delays in catheter laboratory activation and delivery of reperfusion therapy, and, ultimately, worse clinical outcomes.

Case report

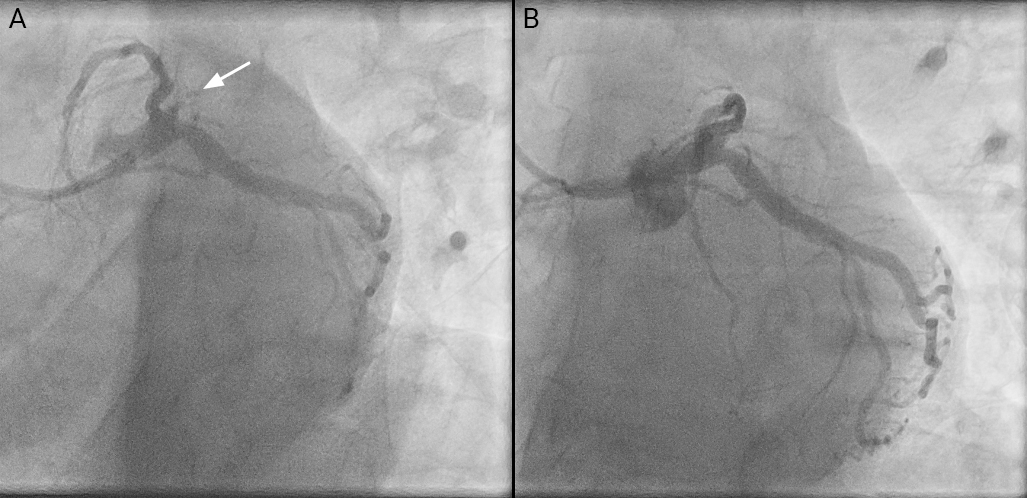

A 44-year-old man with a background of hypertension and paraplegia presented with acute chest pain radiating to the left arm, which woke him from sleep. He called for emergency medical assistance, and an ECG, performed by paramedics, showed ST-segment elevation in leads aVL and V2 and ST-segment depression in leads II, III and aVF. This ECG pattern (figure 1A) forms what has been labelled as the ‘South African flag’ pattern (figure 1B), and it is associated with high diagonal or intermediate artery occlusion.1 Urgent coronary angiography was undertaken via right radial approach and showed acute occlusion at the ostium of the intermediate artery. This was only visible with a very steep left anterior oblique (LAO) (40 degree) caudal (40 degree) view (white arrow, figure 2).

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was undertaken using a Fielder XT-A wire introduced via a 6F EBU 3.5 guide and a 2 mm semi-compliant balloon to restore flow. Intravascular ultrasound showed the intermediate to be 4 mm in diameter proximally with predominantly fibrous plaque and minimal calcification at the site of occlusion. There was diffuse disease elsewhere in the vessel, which was treated with cutting balloon then non-compliant balloon angioplasty, followed by drug-eluting stent implantation, and further treatment with a paclitaxel-coated balloon to the ostium, avoiding interference of the left main stem (LMS) trifurcation with a metallic stent. Post-procedure angiography confirmed normal flow in the treated vessel with no significant residual stenosis, and complete resolution of chest pain and ST-segment changes.

Discussion

Diagonal and intermediate arteries, while considered secondary branches of the left anterior descending (LAD) and circumflex coronary arteries often supply substantial myocardial territories. Acute occlusion results in ischaemic damage with the potential for arrhythmia. Under-recognition of this, and also obtuse marginal artery occlusions, arises from atypical ECG changes, including non-contiguous ST-segment elevation, ST-depression or sometimes no significant ST-segment change.2 Current ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) protocols favour detection of LAD/right coronary artery (RCA)-related infarcts, resulting in the potential for delay in diagnosis of less familiar patterns, which may only be suspected when the results of troponin tests are available. While the high-lateral leads, such as aVL, may have utility in identifying diagonal or intermediate artery involvement,3 studies have shown that 25% of patients without ST-elevation have occlusive myocardial infarction (OMI), although they display a variety of other patterns of ST-depression or T-wave changes.4

There is a lack of familiarity of these patterns among clinicians, and even some cardiologists.4 In this respect, the use of artificial intelligence (AI)-guided ECG interpretation can assist paramedics and emergency clinicians to recognise these patterns as indicative of OMI and decide to refer the patient urgently,5 and AI-augmented ECG analysis may also assist the cardiologist in their decision to offer immediate angiography.6,7 Recognition of this ECG pattern played an important role in this case, and led to coronary angiography with suspicion of OMI (figure 1C). Luck may be defined as the intersection of preparation and opportunity. In this case, AI-identified ECG changes associated with OMI and the pattern allowed us to suspect the intermediate artery and deliver acute and effective reperfusion therapy.

Conclusion

This case emphasises the importance of recognising non-classical ST-segment changes, such as the ‘South African flag’ pattern for diagnosing diagonal or intermediate artery occlusion in acute MI, and the potential role of AI-assisted ECG interpretation. Timely intervention ensured successful revascularisation and optimal patient outcome.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Patient consent

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the patient, to whom the authors are very grateful for him allowing us to publish this case.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the expertise of the catheter laboratory team who provided care to the patient including Jaysson Crusis, senior radiographer; Melisa Bolat, cardiac physiologist; Thea Galeon, scrub nurse; and the expertise of the nursing staff on the coronary care unit led by Breege Skeffington, who provided all the pre- and post-catheter laboratory care.

References

1. Durant E, Singh A. Acute first diagonal artery occlusion: a characteristic pattern of ST elevation in noncontiguous leads. Am J Emerg Med 2015;33:1326e3–1326e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2015.02.008

2. Huey BL, Beller GA, Kaiser DL, Gibson RS. A comprehensive analysis of myocardial infarction due to left circumflex artery occlusion: comparison with infarction due to right coronary artery and left anterior descending artery occlusion. J Am Coll Cardiol 1988;12:1156–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/0735-1097(88)92594-6

3. Hassen GW, Talebi S, Fernaine G, Kalantari H. Lead aVL on electrocardiogram: emerging as important lead in early diagnosis of myocardial infarction? Am J Emerg Med 2014;32:785–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2014.02.038

4. McLaren J, de Alencar JN, Aslanger EK, Meyers HP, Smith SW. From ST-segment elevation MI to occlusion MI: the new paradigm shift in acute myocardial infarction. JACC Adv 2024;3:101314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacadv.2024.101314

5. Martinez-Selles M, Marina-Breysse M. Current and future use of artificial intelligence in electrocardiography. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2023;10:175. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd10040175

6. Iannattone PA, Zhao X, VanHouten J, Garg A, Huynh T. Artificial intelligence for diagnosis of acute coronary syndromes: a meta-analysis of machine learning approaches. Can J Cardiol 2020;36:577–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.09.013

7. Herman R, Meyers HP, Smith SW et al. International evaluation of an artificial intelligence-powered electrocardiogram model detecting acute coronary occlusion myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J Digit Health 2024;5:123–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjdh/ztad074