This case report highlights the clinical course of a young patient with a history of ischaemic cardiomyopathy and severely impaired left ventricular (LV) systolic function following a delayed anterior myocardial infarction, which was further complicated by the presence of large LV thrombus. The patient subsequently presented with persistent ventricular tachycardia (VT) refractory to multiple anti-arrhythmic medications and antitachycardia pacing (ATP). VT ablation was contraindicated due to the LV thrombus, and the failure of conventional medical therapy. Heart transplantation was considered as the final viable management strategy. This case highlights the complexity of managing patients with advanced heart failure and ventricular arrhythmias, emphasising the importance of timely consideration of advanced therapeutic options in refractory scenarios.

Introduction

Ventricular tachycardia (VT) is a well-recognised arrhythmia, commonly caused by scar-related aetiology. Here, we present the case of a patient in their mid-thirties with incessant VT refractory to combination anti-arrhythmic therapy and antitachycardia pacing (ATP). This report highlights the clinical challenges encountered during management and explores therapeutic strategies, offering insights into the complexities of addressing drug-resistant VT. The discussion emphasises the importance of individualised treatment approaches in challenging cases, considering the risks and benefits of available interventions.

Case

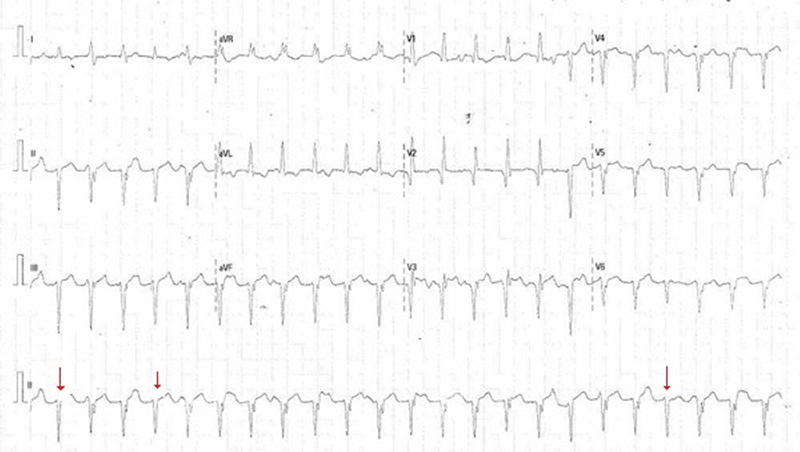

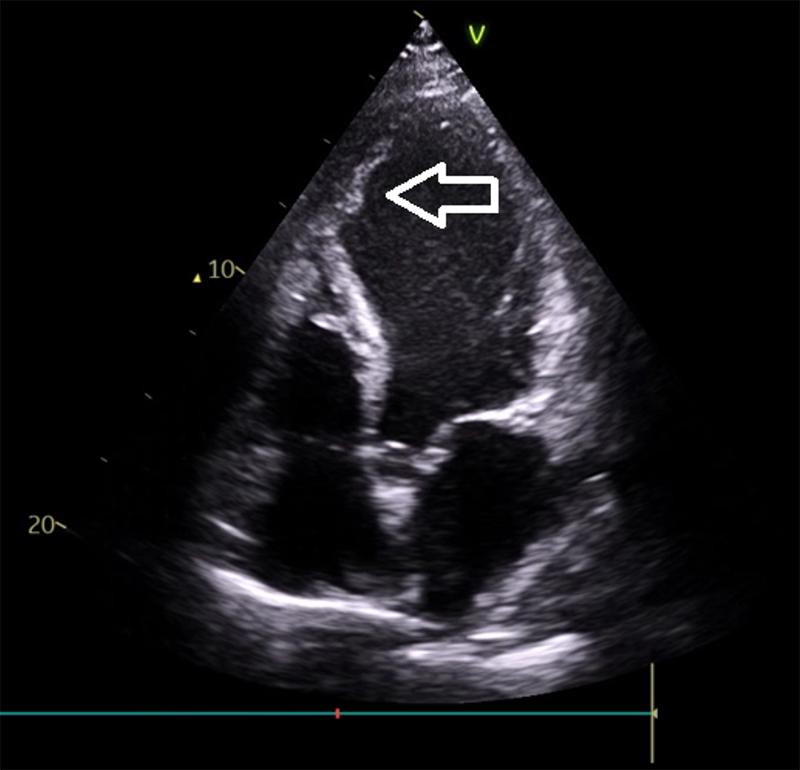

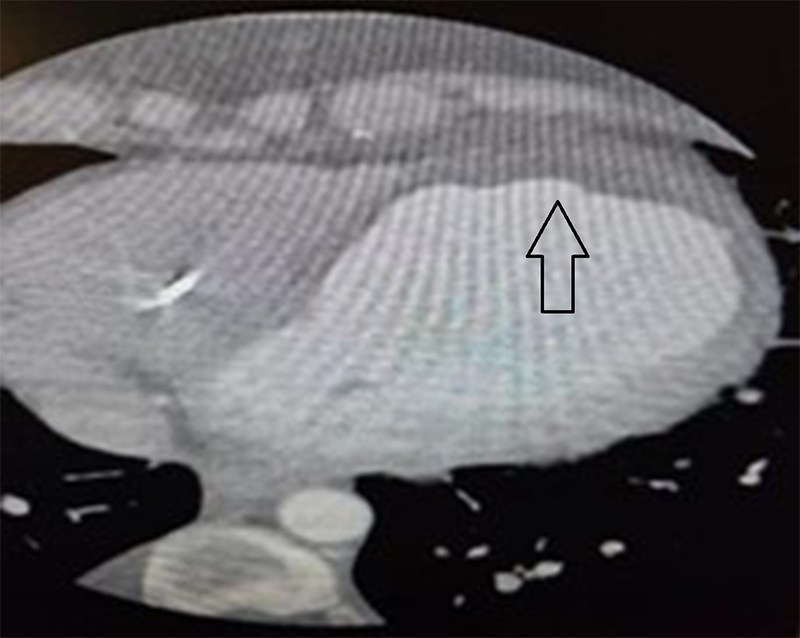

A patient in their thirties presented with chest pain, palpitations, and syncope, found to be in slow VT (figure 1). Past medical history included a late presenting large anterior wall myocardial infarction (MI) six months prior, heart failure with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) 25%, left ventricular (LV) thrombus previously managed with apixaban, and a primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). Multiple anti-arrhythmic agents, including beta blockers, amiodarone and lidocaine, failed, either due to side effects or lack of efficacy. Oral mexiletine was considered, but not used as intravenous lidocaine was not effective. ATP via the implanted ICD only very briefly restored sinus rhythm and was ineffective. Due to the presence of a large LV thrombus (figures 2 and 3) and, therefore, risk of stroke, synchronised cardioversion and acute VT ablation were not attempted. Laboratory work-up was entirely normal. This case highlights the challenges of managing refractory VT in a young patient with structural heart disease and limited procedural options.

|

|

Discussion

VT can arise from a range of conditions, with ischaemic heart disease being the most common aetiology. Post-MI scarring often serves as the substrate for re-entrant VT. Non-ischaemic causes include dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, electrolyte imbalances, drug-induced QT prolongation, and inherited channelopathies.

Heart transplantation is a treatment option in advanced medically refractory heart failure and carries a European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Class I recommendation for appropriately selected patients.1 This includes those with advanced heart failure refractory to medical and device therapy.1

A study by Martins et al., involving 45 patients listed for heart transplantation due to refractory electrical storm, reported a one-year survival rate of 68.9%.2 The mean age of selected patients was 55 years. The median LVEF was 25%. Out of the 45 patients selected for the study, 19 had an underlying diagnosis of non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy, 12 had a diagnosis of ischaemic cardiomyopathy, and the remaining patients had congenital heart disease, arrhythmogenic right ventricular, hypertrophic or lamin A/C mutation cardiomyopathies. Notably, three out of all patients selected for the study experienced electrical storm triggered by acute coronary syndrome.2 Mortality during hospitalisation was predominantly attributed to non-cardiac adverse events, including respiratory sepsis and intracerebral haemorrhages.2 Importantly, survivors at hospital discharge exhibited significantly better pre-operative renal function, as evidenced by lower serum creatinine and urea levels. These findings emphasise the strong association between preserved renal function prior to transplant and favourable postoperative survival outcomes.2 These findings also suggest that heart transplantation can be considered a viable treatment option for refractory electrical storm, particularly in carefully selected patients where other therapeutic interventions have failed or are considered high risk.

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Rashid et al. compared catheter ablation (CA) and antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs) for treating VT across 18 randomised-controlled trials involving over 1,500 participants.3 Both CA and AADs significantly reduced recurrence of ventricular arrhythmias (VA) and, therefore, subsequent ICD interventions, with no significant difference between the two treatment approaches in overall mortality reduction. There is evidence to suggest that a key disadvantage of AADs is their lower efficacy in preventing slow VT, which may lead to heart failure and increased hospitalisation.4

The current ESC guidelines, including the 2022 updates, do not explicitly list heart transplantation as a recommended treatment for refractory electrical storm (ES).5 The guidelines primarily emphasise optimising medical management, including AADs, CA, autonomic modulation, and mechanical circulatory support for patients with severe VA or ES.5 Heart transplantation is primarily addressed in ESC guidelines as a treatment for advanced heart failure.1

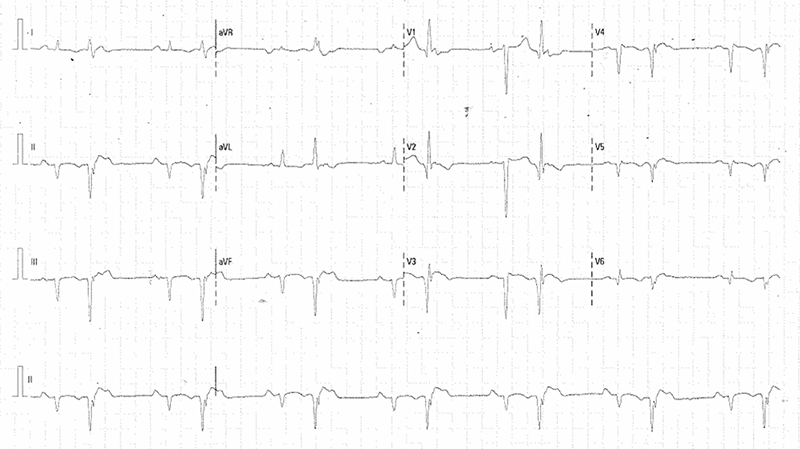

The VT shown in figure 1 was unusual due to relatively narrow QRS duration, in contrast to typical monomorphic scar-related VT. The extreme QRS axis indicated by positive complex in aVR, as well as several ‘capture beats’, indicated by red arrows, that do not show the notching observed of the upslope of QRS observed in other beats, confirm that the arrhythmia is indeed VT. These ‘capture beats’ have similar QRS morphology to the baseline QRS morphology seen in figure 4, confirming successful anterogradely conducted sinus beat. Similarly, the morphology of the ventricular ectopic beats are similar to VT morphology. Repeated ICD interrogation established VT and ruled out aberrantly supraventricular tachyarrhythmias.

In this patient, refractory VT persisted despite multiple antiarrhythmic therapies. The presence of a LV thrombus precluded catheter ablation as a treatment option, despite its organised appearance. The electrophysiology team advised against ablation due to the significant risk of thromboembolic complications, including stroke. Although cardioversion was recognised as carrying a high embolic risk given the well-formed thrombus, it remained a potential consideration in the event of clinical deterioration. Finally, combination therapy with high-dose bisoprolol and sotalol was utilised as a final attempt at medical therapy. This unusual combination proved to be efficacious and permitted safe discharge for a review at a specialist cardiac centre. As a result, heart transplantation was no longer considered following resolution of VT with this dual beta blocker therapy.

Conclusion

This case highlights the complex decision-making required in managing VA in the context of severe heart failure when conventional treatments are contraindicated or ineffective. The complexities in managing refractory VT complicated by an LV thrombus are emphasised. When standard treatments are unsuccessful or contraindicated, referral to a heart transplantation centre in appropriately selected patients may be considered for definitive intervention.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Patient consent

The patient provided written consent for publication. All attempts were made to ensure patient confidentiality was maintained.

References

1. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M et al. 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021;670:3599–726. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368

2. Martins RP, Hamel-Bougault M, Bessière F et al. Heart transplantation as a rescue strategy for patients with refractory electrical storm. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2023;12:571–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjacc/zuad063

3. Rashid A, Khan MF, Rashid J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of catheter ablation versus anti-arrhythmic drugs for treatment of ventricular arrhythmia. Cureus 2024;16:e67649. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.67649

4. Arenal Á, Ávila P, Jiménez-Candil J et al. Substrate ablation vs antiarrhythmic drug therapy for symptomatic ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;79:1441–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.01.050

5. Zeppenfeld K, Tfelt-Hansen J, de Riva M et al. 2022 ESC guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death. Eur Heart J 2022;43:3997–4126. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac262