We previously reported retrospective data on the place of death for people with heart failure (HF) known to heart failure nurse specialists (HFNS) working in two integrated cardiology palliative care teams. Here, we present prospective data on place of death, the supportive services accessed, and the role of HFNS.

We collected prospective data on all patients known to the HFNS, who died during one year (n=126): length of HFNS involvement; planning for end-of-life care; preferred and actual place of death; services accessed. Outcomes were compared for the two teams.

The Surprise Question was applicable in 70% of patients; 89% of whom died within 12 months. Overall, 33% died in hospital. Planning for end-of-life care was evident for 64% and half were referred for specialist palliative care; mostly initiated by HFNS. Preferred place of death was achieved for 61%. Home death was more common where there was greater access to hospice-at-home and Marie Curie nurses. Hospital death was least likely in the team with an out-of-hours palliative care telephone service.

In conclusion, recognition and planning for the end of life is possible for many with HF. HFNS were central in discussing patients’ concerns, providing and coordinating end-of-life care.

Introduction

Landmark qualitative studies published within the last decade highlighted inequalities in end-of-life care between people with advanced heart failure (HF) and cancer.1-8 A palliative approach and access to specialist palliative care (SPC) services for people with advanced HF is now underlined in national and international policy.9-14 However, those with HF are still more likely to die in hospital in the UK than cancer patients,15 and UK 2010 national audit figures document less than 4% of people with HF referred for palliative care.16 Hospice referral seems higher in the USA and Canada.17,18

Landmark qualitative studies published within the last decade highlighted inequalities in end-of-life care between people with advanced heart failure (HF) and cancer.1-8 A palliative approach and access to specialist palliative care (SPC) services for people with advanced HF is now underlined in national and international policy.9-14 However, those with HF are still more likely to die in hospital in the UK than cancer patients,15 and UK 2010 national audit figures document less than 4% of people with HF referred for palliative care.16 Hospice referral seems higher in the USA and Canada.17,18

We have previously reported retrospective data showing recognition of advanced disease and a low rate of hospital deaths in people dying from advanced HF.19 Given the limitations of retrospective data, we were unable to assess use of supportive and SPC services.

The Scarborough service has two heart failure nurse specialists (HFNS) managing 192 new referrals a year from a population of 160,000 in a predominantly rural area. Two community hospitals with SPC supported beds; a 16-bedded SPC hospice and nursing homes provide an alternative setting to the acute hospital. A cardiology–SPC multi-disciplinary team (MDT) meets twice monthly and a 24-hour palliative care out-of-hours phone advisory service is available to patients, carers and health professionals (PalCALL, based at the hospice20). Marie Curie nurses are available to support dying patients at home, but this was a relatively rare resource. There is no hospice-at-home service.

In Bradford/Airedale, seven HFNS manage 293 new referrals per year from a population of 500,000 in a predominantly urban area. Palliative care beds are provided in two 16-bedded SPC hospices. Hospice-at-home and Marie Curie nurses (as part of the Better Together project supported by Marie Curie Cancer Care and the British Heart Foundation) supplement community nursing care. Strong links exist between the cardiology and SPC teams, but there is no formal MDT meeting. Out-of-hours phone advice is provided for health professionals by the palliative physicians.

We aimed to prospectively assess the care received by patients with advanced HF, known to both teams with regard to the following:

- evidence of recognition of advanced HF in people who died within 12 months of referral or re-referral to the service

- evidence of planning of end-of-life care in relation to actual place of death

- supportive and palliative care services accessed.

Subsidiary aims included a descriptive comparison between the two teams to explore factors in any observed differences in place of death.

Method

Data collection

A data collection sheet was used for all new referrals to HFNS from January to December 2009 (Bradford/Airedale) and April 2009 to March 2010 (Scarborough).

Age, sex and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class (at initial referral) were recorded. The following dates were noted: referral to the HFNS; the Surprise Question (“I would not be surprised if the patient died within the next 12 months”) agreed; referral to SPC; do-not-attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNA-CPR) order; implantable cardioverter device (ICD) re-programmed; preferred place of care discussed. We recorded which services were accessed and whether anticipatory end-of-life medication was dispensed. Those involved in planning discussions were noted and whether the patient lived alone. The date, place and mode (sudden or expected) of death were recorded.

We counted the Surprise Question, documentation of preferences, re-programming ICD/DNR-CPR decisions, placement of anticipatory medication, and use of the Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP) as evidence of planning for end-of-life care.

Research ethics approval was not required for this service evaluation survey.

Data analysis

Data from individual anonymised data collection sheets were entered into a bespoke designed Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (2007). All patients dying during the period of data collection were included in the data analysis. The data were analysed using descriptive statistics, including median, mean, standard deviation, quartiles, range and percentages.

Results

Demographics and stage of disease

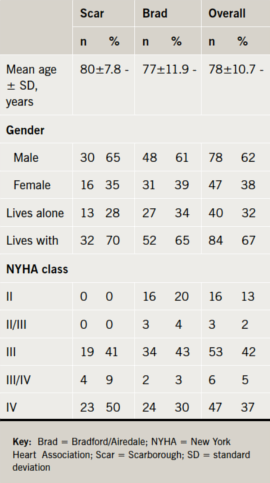

The demographic description of the patients can be seen in table 1.

Time points until death

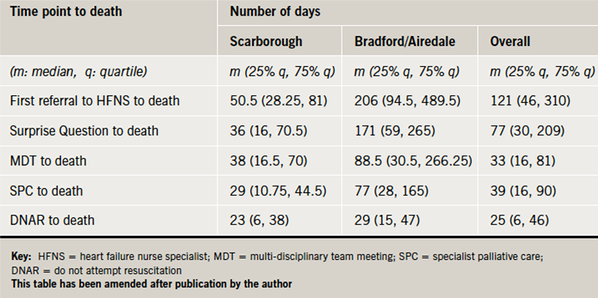

Table 2 describes the length of time (days) from death to the preceding time points. The HFNS in Bradford/Airedale had the patients on their caseload for longer. Durations from time points to death were correspondingly longer in the Bradford/Airedale team except for the timing of DNA-CPR decisions, which were similar in both areas; three to four weeks before death.

The Surprise Question was agreed in 88/126 (70%) of the sample; 78 of these people (89%) died within 12 months.

Use of supportive care services

Overall, 56% patients used supportive care services. Services accessed were similar, except that some Bradford/Airedale patients accessed psychologist, dietitian and respite services and a heart failure support group, where Scarborough patients did not.

Planning for end-of-life care and preferences for place of care/death

The HFNS documented planning for end-of-life care for 36/46 (78%) in Scarborough and 44/80 (55%) in Bradford/Airedale, most commonly initiated by the HFNS (57/80; 71%). A DNA-CPR decision was made in 33/46 (72%) Scarborough patients and 25/80 (31%) Bradford/Airedale patients. No Scarborough patient required ICD re-programming, compared with four in Bradford/Airedale (5%). This was done 7–37 days before death (mean 20 days) – in keeping with the timeframe for DNA-CPR decisions.

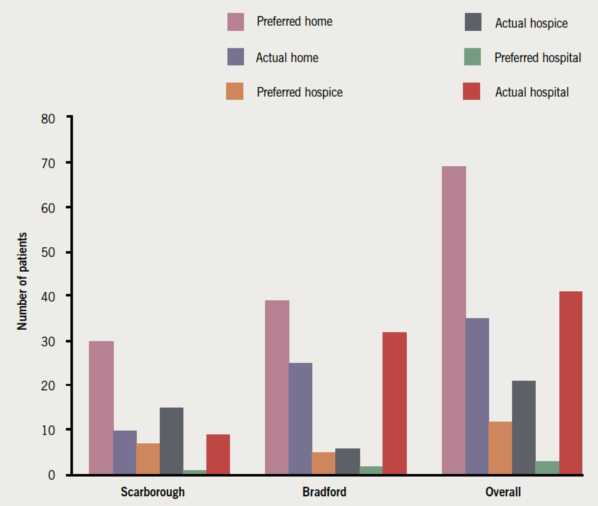

The preferred place of death was known in 78% of Scarborough patients and 55% in Bradford/Airedale patients. Where known, it was achieved in 61% (figure 1). Most wished to die at home, achieved more often in Bradford/Airedale than in Scarborough (25/39 vs. 10/30 [actual/stated preference]). Scarborough had more hospice deaths than Bradford/Airedale (15/7 vs. 6/5). Bradford/Airedale had more hospital deaths than Scarborough (32/3 vs. 9/1).

About one-fifth were classed as ‘sudden cardiac deaths’. The LCP was used to care for 23/46 (50%) of patients in Scarborough and 19/80 (24%) in Bradford/Airedale. The ‘four key drugs’ of anticipatory home prescribing were only available for 20/126 (16%) overall.

Use of specialist palliative care services

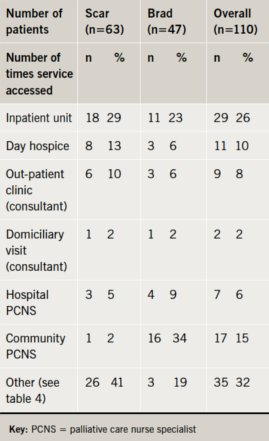

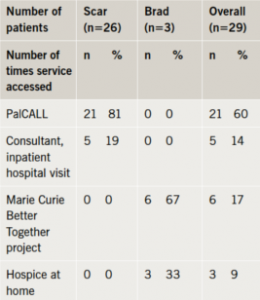

About half the patients had used SPC services (tables 3 and 4), though this was more common in Scarborough (72% vs. 34%) where some were registered for the PalCALL service, but did not need any other.

Most patients had been referred to SPC services by the HFNS (41/57; 72%).

Overall, 87 (74%) accessed rehabilitation and social services with 59 (72%) in Bradford and 28 (78%) in Scarborough. District nursing services were required by 12 (10%) with no difference in either area. Other services such as psychology, support groups, dietitian, sitting service, respite and complementary therapies were used by 19 (16%).

Discussion

Recognising advanced disease

The vast majority of patients died within 12 months of the Surprise Question being judged to be relevant. However, the design of this prospective survey means we do not have data on patients for whom the Surprise Question was judged relevant, but who did not die (thus we cannot estimate specificity). The Surprise Question is an expression of clinical judgement, and will have different sensitivity and specificity dependent upon many factors, not least, the experience of the clinician making the judgement. Here, the situation is assessed by experienced nurse specialists. Interestingly, general practitioners have reported uncertainty in their ability to judge when a patient has reached end-stage disease.21

Planning for end-of-life care and preferences for place of care/death

End-stage disease had been recognised and planned for in nearly two-thirds of patients. The HFNS discussed and coordinated such plans with patients more frequently than any other professional.

Data concerning documentation of patients’ preferences and actual place of death are consistent with our retrospective data,19 and are higher than the 31% of achieved preferences in the Glasgow and Clyde area.22

Planning for end-of-life care as a process

End-stage disease was recognised, on average, 171 days (Bradford/Airedale) before death, but a DNA-CPR decision was not in place until within a month of death. This illustrates that planning for end-of-life care is a process rather than a single event. The DNA-CPR decision may be the outcome of several weeks’ gentle rapport building and sensitive discussion with patients and families who have not realised they have advanced disease and have unrealistic expectations of CPR.

Differences between the two services

Scarborough patients were referred at a later stage (50% had class IV heart failure at referral vs. 30% in Bradford/Airedale), reflected in the shorter time on the HFNS caseload before death. This has implications for the time patients and carers can be supported; some may have benefited from and been referred to supportive services earlier. In addition, they may have had optimisation of HF medication not tolerated in late disease.

Highly complex patients with difficult symptoms and communication issues are time consuming. The Glasgow and Clyde Report showed that when the HFNS addressed supportive and palliative care needs, the average time taken for a home visit increased from 20 minutes to 1.5 hours.23 There appears to be little consistency in workforce planning for HFNS, which, given their key role in optimising treatment and preventing hospital admission, is notable.

The Bradford/Airedale service had more home deaths despite more patients living alone. They had access to hospice-at-home nurses and Marie Curie nurses as part of the Better Together project. ‘Hands on’ nurses for whole shifts provide robust home care, especially out of hours when deteriorations may otherwise lead to admission. Hospice deaths were more common, and hospital deaths less so in Scarborough than in Bradford/Airedale, which, although hospital deaths were less than national figures, mirrored Glasgow and Clyde’s hospital deaths of 25/126 (44%).23 Approximately half the Scarborough patients were registered with the PalCALL service, which records the preferred place of care/death and liaises directly with the out-of-hours GP service. This may help reduce hospital admissions: patients are redirected to the hospice if staying at home is no longer desired or possible (e.g. if sufficient additional care at home is unavailable). In both areas, hospital deaths were markedly less than the 83% of people with HF that died in an acute hospital or elderly care bed in 2002 in the UK.15 Even a ‘sudden cardiac death’ may occur on the background of progressive deterioration which has made a DNA-CPR decision appropriate, obviating the need to call an ambulance.

A recent systematic review found little evidence of discussions of end-of-life care with HF patients.24 Although these observational data are low level evidence, it nevertheless reports discussions that are taking place, facilitated by the presence of a functional integrated team.

Strengths and limitations

The data were collected by busy HFNS, and, therefore, some may have been omitted. Data collected on patients thought to be within the last year of life, but who did not die within this timeframe, would have allowed a sensitivity and specificity to be calculated. Also, larger numbers from more teams would give a broader picture. However, this shows what is possible in daily practice with no additional resources, a description of the supportive and palliative care services accessed to implement end-of-life care, and an indication of the timing of end-of-life discussions.

Implications for future research or clinical practice

Achievement of the patient’s end-of-life preferences requires a coordinator with advanced communication and clinical skills. Services should address the implications of the time needed to address palliative care needs, the decision-making guides (e.g. LCP), and the services required to support patient preferences at the end of life. This approach is described well by the Innovative Care for Chronic Conditions (ICCC) framework.25

Conclusion

It is possible to recognise advanced disease in HF and to talk with most patients about end-of-life care. Awareness of, and support for, their preferences can reduce the number of hospital deaths. The HFNS is a crucial healthcare professional and can coordinate assessment of need, sensitive discussion and access to appropriate care. They require the committed support of SPC teams.

Acknowledgements

This work could not have been completed without the hard work and dedication of the following HFNS: Sharon Parson, Janet Raw, Sharon Stockdale, Rebecca Fogell, Debbie Gibbon, Sharon Grimsdale, Tracy

Hellawell, Pauline Park and Liz Coupland.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Key messages

- The heart failure nurse specialist is a key team member in the co-ordination of end of life care for people with heart failure

- It is possible to discuss preferences for end of life and management decisions with many patients

- ‘Do not attempt resuscitation’ decisions may require gentle discussion over time

- An integrated team with cardiology, palliative care and general practitioner clinicians can help prevent unwanted hospital admissions at the end of life

References

- Murray SA, Boyd K, Kendall M, Worth A, Benton TF, Clausen H. Dying of lung cancer or cardiac failure: prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers in the community. BMJ 2002;325:929. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7370.929

- Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Worth A, Benton TF. Exploring the spiritual needs of people dying of lung cancer or heart failure: a prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers. Palliat Med 2004;18:39–45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/0269216304pm837oa

- Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Sheikh A. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ 2005;330:1007–11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1007

- Murray SA, Kendall M, Grant E, Boyd K, Barclay S, Sheikh A. Patterns of social, psychological, and spiritual decline toward the end of life in lung cancer and heart failure. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;34:393–402. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.12.009

- Rogers A, Addington-Hall JM, McCoy AS et al. A qualitative study of chronic heart failure patients’ understanding of their symptoms and drug therapy. Eur J Heart Fail 2002;4:283–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1388-9842(01)00213-6

- Rogers AE, Addington-Hall JM, Abery AJ et al. Knowledge and communication difficulties for patients with chronic heart failure: qualitative study. BMJ 2000;321:605–07. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.321.7261.605

- Gott M, Barnes S, Parker C et al. Dying trajectories in heart failure. Palliat Med 2007;21:95–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0269216307076348

- Selman L, Harding R, Beynon T et al. Improving end-of-life care for patients with chronic heart failure: “Let’s hope it’ll get better, when I know in my heart of hearts it won’t”. Heart 2007;93:963–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2006.106518

- Arnold JM, Liu P, Demers C et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society consensus conference recommendations on heart failure 2006: diagnosis and management. Can J Cardiol 2006;22:23–45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0828-282X(06)70237-9

- Department of Health. National Service Framework for coronary heart disease – modern standards and service models. London: Department of Health, 2000.

- Department of Health. End of Life Care Strategy – promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life. London: Department of Health, 2008.

- Goodlin SJ, Hauptman PJ, Arnold R et al. Consensus statement: palliative and supportive care in advanced heart failure. J Card Fail 2004;10:200–09. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2003.09.006

- Jaarsma T, Beattie JM, Ryder M et al. Palliative care in heart failure: a position statement from the palliative care workshop of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2009;11:433–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurjhf/hfp041

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Chronic heart failure: management of chronic heart failure in adults in primary and secondary care. London: NICE, 2010. Available from: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG108

- Beattie JM. The burden of advanced heart failure: an instrument to facilitate population based needs assessment for the provision of palliative/supportive care for management of this chronic progressive disease. London: National Health Services, 2005.

- The NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care. National Heart Failure Audit. Report for the Audit period between April 2009 and March 2010. Leeds: NHS Information Centre, 2010.

- Kaul P, McAlister FA, Ezekowitz JA et al. Resource use in the last 6 months of life among patients with heart failure in Canada. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:211–17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2010.365

- Unroe KT, Greiner MA, Hernandez AF et al. Resource use in the last 6 months of life among medicare beneficiaries with heart failure, 2000–2007. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:196–203. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2010.371

- Johnson M, Parsons S, Raw J, Williams A, Daley A. Achieving preferred place of death – is it possible for patients with chronic heart failure? Br J Cardiol 2009;16:194–6.

- Campbell C, Harper A, Elliker M. Introducing ‘Palcall’: an innovative out-of-hours telephone service led by hospice nurses. Int J Palliat Nurs 2005;11:586–90.

- Hanratty B, Hibbert D, Mair F et al. Doctors’ perceptions of palliative care for heart failure: focus group study. BMJ 2002;325:581–5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7364.581

- Pattenden JF, Mason A. Better together: an end of life initiative for patients with heart failure and their families. London: British Heart Foundation, 2010.

- Millerick Y, Wright J, Freeman A. British Heart Foundation heart failure palliative care project report: The Glasgow and Clyde experience. Final Report October 2010. London: British Heart Foundation, 2010.

- Barclay S, Momen N, Case-Upton S, Kuhn I, Smith E. End-of-life care conversations with heart failure patients: a systematic literature review and narrative synthesis 1. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e49–e62. http://dx.doi.org/10.3399/bjgp11X549018

- World Health Organization. Innovative care for chronic conditions: building blocks for action. Global Report. Geneva: WHO, 2002.