Familial hypercholesterolaemia is a common genetic disorder that remains under-recognised. At present a simple genetic test is not available, although targeted genetic screening is being piloted in the UK. Recognition and treatment of this condition could help prevent many incidences of coronary heart disease. This article provides an overview of the pathophysiology, epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment of familial hypercholestrolaemia.

Introduction

Familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) is a common genetic disorder in people of European and Japanese descent, affecting about one in 500 people in its heterozygous form. It is characterised by high levels of total and low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol and, with its predilection for affecting proximal coronary arteries, is the most important clinical syndrome leading to premature coronary heart disease (CHD). Despite huge advances in unravelling the complex pathophysiology of the syndrome and the effectiveness of modern treatments, awareness of the syndrome and its consequences remains low and affected individuals are still overlooked and denied the potential benefits of treatment.

Pathophysiology

The major role of LDL-cholesterol is to deliver cholesterol to cells for membrane repair and growth. LDL-cholesterol enters cells either by direct (concentration dependent) passage through the cell membrane or via surface LDL-receptors that actively bind LDL-cholesterol in invaginations of the cell membrane. The LDL-cholesterol is internalised, eventually forming endosomes, the contents of which are degraded to release amino acids and free cholesterol for use in the cell. The LDL-receptors are also released and travel back to the surface again, the whole cycle taking about 10 minutes.

The underlying defect of FH is a mutation in the LDL-receptor pathway. More than 1,000 different genes encoding LDL-cholesterol uptake and catabolism have now been identified and this means FH should be viewed as a clinical syndrome, i.e. a similar phenotype arising from multiple genotypes. Defects have been described in the synthesis of the LDL-receptor, its transport to the cell surface and its binding to LDL-cholesterol. Other defects include failure of LDL-cholesterol internalisation and the release of LDL-receptors from endosomes. Whatever the defect, however, the net result is a build up of LDL-cholesterol in tissue fluid and plasma, and as LDL-cholesterol concentrations rise, more uptake into cells.

Apart from rare instances, the syndrome of FH is dominantly inherited. An affected parent has a 50/50 chance of passing on the dominant gene to each offspring. If the frequency of heterozygotes is one in 500, then the chance of two affected individuals producing a pregnancy together is one in 250,000. One child from this union would be normal, two would have heterozygous FH and one homozygous FH. Strictly speaking, because of the number of individual mutations involved in the FH syndrome, these homozygous individuals are really compound heterozygotes and only if the same mutation was involved would a true homozygote result. There are about 110,000 individuals in the UK heterozygous for FH but probably less than 50 homozygotes.

Signs and symptoms

The hallmark lesion of FH is the tendon xanthoma, essentially localised infiltrates of lipid-rich foam cells in the tendons themselves. Typically overlying the knuckles of the hands or in the Achilles tendons (figures 1 and 2), xanthomata may appear from the age of 20 onwards (earlier in homozygotes) but 20% of individuals have no xanthomata at all by the time of death. Almost exclusively, the presence of xanthomata means FH but not having them does not exclude FH. Tendon xanthomata are hard because of collagen infiltration and can become inflamed. Patients with FH often complain of Achilles tenosynovitis and may even present to orthopaedic specialists. Xanthelasma of the eyelids and corneal arcus also appear in FH but less commonly than in other forms of hyperlipidaemia and their presence is not helpful in diagnosis.

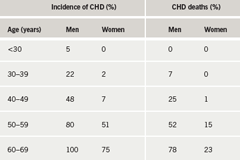

The main feature of FH is the premature manifestation of CHD. This can be as early as the 20s in heterozygotes and even earlier in homozygotes. Pre-statin studies show that by the age of 50, about half of men have had a CHD event and women reach the same level about a decade later (table 1).

Although FH has a remarkable predilection for coronary vessels, atheroma is also seen in cerebral vessels and occasionally peripheral arteries. Cholesterol deposits remarkably similar to atheroma develop in the aortic root and aortic valve and may require surgery.

The age at which CHD manifests in affected families can vary but, where consistent, can be useful in deciding when to start drug treatment in younger people. When they co-exist, smoking, high blood pressure and obesity all dramatically worsen the outlook for FH patients.

Epidemiology

Of the estimated 110,000 people with FH in the UK it is thought that only 20,000–30,000 are recognised. Although about as common as type 1 diabetes mellitus, this lack of recognition implies that both lay people and health professionals lack awareness of the syndrome, its diagnostic features and consequences. Framingham-based cardiovascular risk assessment should exclude individuals with extreme hypercholesterolaemia but health professionals still, sometimes falsely, reassure FH patients that they are of low global cardiovascular risk. Despite lack of awareness, there is no doubt that FH can be hard to recognise for a number of reasons. Physical signs may be absent and sometimes there is no background family history of CHD. This usually means that affected relatives are female and have escaped events. FH patients are often younger and look fitter, and health professionals can overlook their ischaemic symptoms. Exercise electrocardiography can be less reliable despite the fact that surprisingly severe coronary atheroma, affecting all three vessels, is often present. In addition, laboratory confirmation is not always straightforward.

Diagnosis

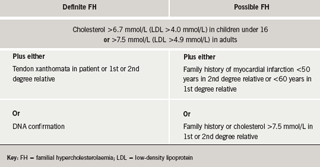

There is no precise cholesterol level that is diagnostic of FH. The average serum cholesterol in adult heterozygotes is around 9 mmol/L and most people with levels over this will have FH. The range however, is from about 7 to 20 mmol/L, and 15–30 mmol/L with homozygotes. In the lower range, there is overlap with other causes of hyperlipidaemia and at a value of 7.0 mmol/L there is only a one in 25 chance of having FH. Values are lower in childhood and screening the children of an affected parent can be difficult. Neonatal levels (e.g. cord blood) are hard to interpret and because of the difficulties modifying diet in very young children, it is pragmatic to test children after two years. Reassurance can be given if serum cholesterol is under 5.5 mmol/L. Several criteria have been derived to guide diagnosis but none are infallible and retesting at 18, after the adolescent growth spurt, is advised. In the UK, we use the criteria of the Simon Broome register (table 2).

In an ideal world, we should be able to confirm FH by identifying the presence of the responsible gene defect. In the UK, the commonest gene accounts for just 4% of cases. A panel of the 55 most common FH genes in the UK might identify 70% of cases and has recently become much cheaper to perform. DNA testing in Holland has proved very successful in identifying affected individuals, particularly by family ‘cascade’ screening, where relatives of known cases are sequentially approached for testing. This appears to be more cost-effective than mass screening and is currently being piloted in the UK.

Treatment

Treatment for FH patients is effective. It is vital not to smoke and to be physically active. Compliance with a lifestyle that optimises weight, reduces fat (particularly saturated and trans fats and dietary cholesterol) and incorporates soluble fibre, plant sterols and soya protein will have the greatest impact on cholesterol levels. Supplementary drug treatment is required with statins first line. Pre-statin mortality from CHD in the UK in FH patients has reduced dramatically from a standardised mortality ratio (SMR) of 8.0 to 2.5, with an overall life expectancy similar to the general population due to a reduced cancer risk, presumably associated with a healthier lifestyle.

HEART UK (www.heartuk.org.uk) has long championed identification of the FH syndrome as well as other genetic dyslipidaemias and provides invaluable support for patients and interested health professionals. The British Heart Foundation continues to highlight premature CHD and National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) FH guidelines are scheduled for August 2008. Wider recognition for FH will increase awareness, improve identification and management and the twin tragedies of missed patients and lost opportunities will be relegated to the past.

Acknowledgement

Clinical photographs courtesy of Dr Stephanie Matthews.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Editors note

An article looking at ‘Low-density lipoprotein-apheresis’, the treatment of choice in homozygous FH can be found on pages 83–5 of this issue.

Key messages

- Familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) is a common genetic disorder in people of European and Japanese descent, characterised by high levels of total and low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol

- The underlying defect of FH is a mutation in the LDL-receptor pathway

- The hallmark lesion of FH is the tendon xanthoma, which may appear from the age of 20 onwards (earlier in homozygotes)

- There is no precise cholesterol level that is diagnostic of FH: the range is from about 7 to 20 mmol/L, and 15–30 mmol/L with homozygotes

- When they co-exist, smoking, high blood pressure and obesity all dramatically worsen the outlook for FH patients