We undertook a seven-year in-depth review of all reported obituaries of medical practitioners in the BMJ to assess the age and disease distribution of mortality of medical practitioners in order to identify relationships between mortality and discipline, ethnicity and other demographic factors. In total, 3,342 obituaries reported in the BMJ from January 1997 to December 2004 were reviewed.

The majority of obituaries were of male doctors. Doctors who qualified in the developed world appeared to live longer (mean age at death of 78 years) than those who qualified in Asia (mean age at death of 70 years). White-European doctors lived significantly longer than doctors from other ethnic groups. There was no significant difference in longevity between doctors working in the primary care sector and those in the secondary care sector. An eighth (12.5%) of doctors died between the ages of 60 and 70 years and, of these, nearly half died between the ages of 61 and 65 years. There were significantly more suicides and accidental deaths in Accident and Emergency (A&E) doctors compared with other specialties.

In conclusion, cardiologists are not immortal and need to retire, as do their colleagues in other specialties. Retirement at ages of 65 years or above would disadvantage nearly one in six medical practitioners. Those likely to be most disadvantaged by a mandatory rise in any retirement age, in terms of reaping the benefits of their pension contributions, are those of a non white-European ethnicity.

Introduction

One is often led to believe that cardiac surgeons are immortal but what about the cardiologist? According to the Office for National Statistics, a man aged 65 in 2003–2005 can expect to live for another 16.6 years. Meanwhile, a woman aged 65 can look forward to a further 19.4 years.1 The increasing longevity of populations in developed countries has led to a range of changes in employment terms and conditions. No longer is there an acceptance of a mandatory retirement age, or a compulsory differential retirement age for men and women in the UK. In addition, numerous consultations and reports have been commissioned surrounding retirement ages and benefits in various professions. Medical practitioners have not been exempt from such consultations, and there are now major changes to the pensions system for all staff in the National Health Service (NHS).

There is a widespread perception that early retirement is associated with longer life expectancy and that later retirement is associated with early death. However, Tsai et al.2 concluded that retiring early, at either 55 or 60 years of age, was not associated with better survival than retiring at 65 years of age in a cohort of industrial workers from the petroleum and petrochemical industries. Mortality was shown to be higher in employees who retired at 55 years of age than in those who continued working. However, there is a paucity of information concerning mortality within the professional group of medical practitioners. Despite the potential reporting bias of obituary columns, these may be a valuable source of information concerning the mortality of medical practitioners, and we have used the information from seven years of obituaries reported in the BMJ to collate information regarding mortality in the medical profession.

Methods

In order to assess the age and disease distribution of mortality of medical practitioners, we carried out an in-depth review into the demography of deaths among doctors between the years of 1997 and 2004. We determined the age distribution of death of all doctors using a seven-year review of all reported obituaries in the BMJ. In addition to age of death, we also performed various analyses of these data to investigate factors such as cause of death, ethnicity, and whether doctors in certain disciplines were more susceptible to an earlier death.

We reviewed all obituaries of doctors reported in the BMJ from January 1997 to December 2004. Data on the following categories were collected: gender, ethnicity, date of birth, date of death, age at death, cause of death, specialty, academic/non-academic, year of qualification and place of qualification. We acknowledge the limitation that these are a collection of data from reported obituaries and might therefore represent biased sampling, but in light of the proportion of entries from each specialty and ethnic group being representative of the current UK workforce, we feel this is a reasonable representation of the medical practitioner workforce cohort.

There was a fairly constant rate of death each year from 1997 to 2004 as judged by a lack of difference in the numbers of obituaries reported, assuming that there was no cap on the number of obituaries printed in the BMJ. Some of the obituaries printed in 1997 were deaths in 1996, and some deaths in 2004 had not yet been reported by the time of analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical methods used for our analysis include mean values, standard deviation and unpaired t-tests. Overall, a total of 3,342 obituaries were reviewed.

Results

Demography

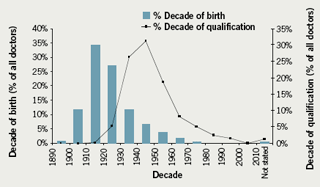

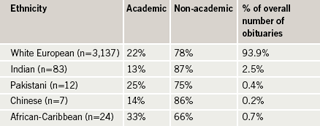

Of all obituaries reviewed, 2,886 (86.4%) were obituaries of male doctors and 456 (13.6%) of female doctors. Figure 1, as one would expect, illustrates a consistent lag of approximately 20 years between year of birth and year of qualification. A total of 93.9% were white Europeans and the majority of the remaining ethnic groups were south Asian (mainly Indian and Pakistani) (table 1).

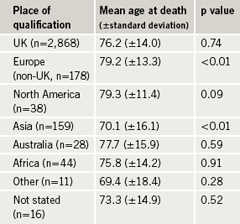

When compared with the overall population of doctors, those who qualified in Europe (non-UK) live significantly longer (mean age of death at 79.2 years; p<0.05) and those who qualified in Asia (mean age at death of 70.1 years; p<0.05) have significantly shorter lives (table 2).

Of all UK graduates, 19.5% qualified from London medical schools. However, a few years in London for these individuals did not appear to have any impact on longevity (mean age at death for London graduates was 76.3 years compared with a mean age at death for non-London graduates of 76.2 years).

Analysis of obituaries by sector of healthcare (i.e. primary versus secondary care; clinical sciences and ‘other’ were excluded from this analysis) revealed that 38% of the reported obituaries were from the primary care sector. This is an accurate reflection of the current primary and secondary care medical workforce distribution where 41% of the current medical practitioner workforce is in the primary care sector. There was no significant difference in longevity between doctors working in the primary care sector and those in the secondary care sector.

When we compared the mean age of death in different ethnic groups with the overall population of doctors (table 3a), white European doctors appeared to live longer than doctors from other ethnic groups, who did not live much beyond the current UK retirement age of 60 years (p<0.05). The age at death for Asian and African-Caribbean doctors was significantly reduced.

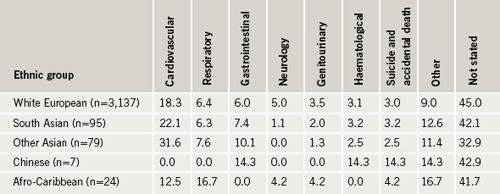

Table 3b shows the causes of death in each ethnic group. We accept that there are a large number of obituaries where the cause of death was not stated, but the proportion of unreported causes of death was similar in each ethnic and age group. Deaths from cardiovascular causes were more likely in south Asians than in white Europeans, and less likely in African-Caribbeans, who appeared to have increased deaths from respiratory causes compared with other ethnic groups (though the numbers in this ethnic group are too small to draw any significant conclusions). Diabetes-related deaths were also more common in south Asians. All reported suicides were in the white European group.

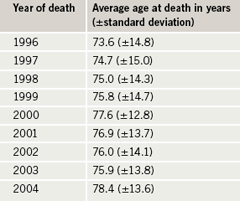

The age at death of doctors appears to be increasing (i.e. doctors are living longer) over the period studied (table 4). Though insignificant, this trend is apparent and consistent with current trends in longevity for the general populations of developed countries.

What do doctors die of?

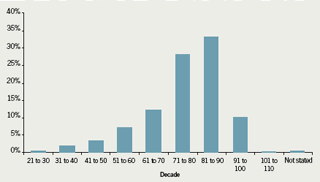

When the age distribution of mortality in all doctors (figure 2) was analysed, 12.5% died between the ages of 60 and 70 years and, of these, nearly half died between the ages of 61 and 65 years.

Table 5 shows that primary care doctors live longer (p=0.01) compared with the overall population of doctors. Accident and Emergency (A&E) doctors, anaesthetists, radiologists, paediatricians, psychiatrists and doctors who practised clinical sciences, died earlier compared with the general cohort of doctors (p<0.05). Cardiologists lived to the age of 73.4 (±13) years. This was a shorter lifespan than dermatologists (76.5 ±13 years) but longer than gastroenterologists (70 ±16 years).

There was no cause of death stated in 44.6% of the obituaries we reviewed. However, in the remainder, the majority of deaths were from cardiovascular causes (figure 3). Cardiovascular deaths were more common in older age groups (the peak being in those born between 1911 and 1920). Cancer-related deaths comprised 22.2% of all stated causes of death. At least 3% of deaths were due to suicide or accidental deaths. Deaths due to suicide occurred in the younger age group (most in those born between 1960 and 1970). Interestingly, deaths due to neurological causes were highest in radiologists.

We found the highest rate of cardiovascular death in diabetologists, and a relatively lower rate of cardiovascular deaths in A&E doctors. However, there were significantly more suicides and accidental deaths in A&E doctors compared with doctors from other specialties.

Discussion

From the demographic data analysed, one clear difference was an almost six-fold higher prevalence of male than female obituaries. This may illustrate under-reporting of female deaths, but more likely, reflects the sex inequality in the senior medical workforce over the last century, which is only now gradually being addressed with policies and strategies to improve equality.

Overall reporting of obituaries by ethnicity closely represents the ethnic composition of the UK general population but not the ethnic breakdown of the current UK medical professional workforce. This is unlikely to be reporting bias, but a reflection that the majority of reported deaths are for practitioners from a time period when the ethnic composition of the workforce was less significant than in today’s workforce.

Lifespan of primary care physicians was similar to secondary care clinicians suggesting little prognostic benefit for a cardiologist seeking a career change to primary care. However, a switch to dermatology does appear to be worth considering for a few extra years of life. Does specialty determine cause of death, however? The most common cause of death was cardiovascular disease, being particularly pronounced in diabetologists (where 41% of deaths were from cardiovascular disease – does diabetology select arteriopathic doctors or does the lifestyle of a diabetologist encourage atherosclerosis?). Radiologists had a tendency to more neurological deaths (is this an effect of radiation?). Although the data show earlier death for A&E doctors, this might merely reflect the relatively young age of this speciality and its younger workforce per se, rather than a truly detrimental effect of working in the emergency department.

Cardiovascular disease appears to be the dominant cause of mortality in south Asian medical practitioners, in line with this being the major cause of morbidity and mortality in the south Asian population as a whole. Perhaps the social class gradient for cardiovascular disease is not as evident in the south Asian population as in other ethnic groups? In contrast, birth on the European mainland appears to confer a prognostic benefit compared with birth in the UK or on the Indian subcontinent.

Interestingly, a few years in London during training does not appear to adversely affect longevity of doctors. The study, however, does show that qualification in countries from the developing world and south Asian ethnicity are associated with a trend towards reduced life expectancy. In particular, south Asian and African-Caribbean doctors tended to have a mean age of death very close to the retirement age of 65 years. Therefore, will plans for a mandatory increase in the retirement age to 65 years deny these groups (namely the African-Caribbean and south Asian doctors) their pension benefits?

The Pensions Commission report led by Lord Turner3 suggested changes to the UK’s pensions system in a bid to address the funding shortfall at retirement. Broadly speaking, the changes amount to higher contributions over the working life of an individual, and a gradual rise in the state retirement age. While it can be argued that an increase in contributions into a pension fund is inevitable if the current pensions ‘black-hole’ crisis is to be arrested, it would be premature to suggest that the life expectancy of an individual will gradually increase in the future based on extrapolation of historic data. Life expectancy does appear to be increasing for medical practitioners as a cohort, as for the general population. This might drive the policy to increasing pensionable age, but at present, this trend is simply that, a trend rather than a significant increase in life expectancy over the past decade and the trend does not apply to all groups within the medical workforce.

Observing the age distribution of mortality shows that an increase in the retirement age from 60 to 65 years will potentially deny 4.6% of doctors their pensions, and increasing it to 70 years will deny 12.5% of doctors their pensions. These figures are even more significant for doctors from ethnic groups, who on average die younger, having contributed similar amounts to the pension pot.

So what does all this tell us about cardiologists? Perhaps the more sedentary a discipline, the longer one’s lifespan? It would be interesting to see if interventionists and non-interventionists differ in life expectancy in due course (if there is a difference in longevity, cause or effect would be an interesting debate). So, cardiologists are not immortal, succumbing in their early seventies, suggesting they still need to retire gracefully as is currently permitted.

Conflict of interest

The authors are medical professionals with pension plans or soon to be medical professionals with the option of pension plans.

Key messages

- Retirement at ages of 65 years or above would disadvantage nearly one in six medical practitioners

- Cardiologists are not immortal

- Working in London does not affect longevity

- Ethnicity appears to impact upon longevity

References

- Office for National Statistics. Life expectancy. Available from: http://www.statistics.gov.uk/cci/nugget.asp?id=168 [accessed June 2008].

- Tsai SP, Wendt JK, Donnelly RP, de Jong G, Ahmed FS. Age at retirement and long term survival of an industrial population: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2005;331:995–7.

- Lord Turner. A New Pension Settlement for the Twenty First Century. London: The Stationery Office, November 2005. Available from: http://www.webarchive.org.uk/wayback/archive/20070801230000/http://www.pensionscommission.org.uk/index.html [Accessed September 2009].