There is increasing evidence for the role of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in the management of patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). However, this intervention has not yet been widely adopted within the National Health Service (NHS).

We performed a feasibility study on the utilisation of an established NHS cardiac rehabilitation programme in the management of AF, and examined the effects of this intervention on exercise capacity, weight, and psychological health. We then identified factors that might prevent patients from enrolling on our programme.

Patients with symptomatic AF were invited to participate in an established six-week exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation programme, composed of physical activity and education sessions. At the start of the programme, patients were weighed and measured, performed the six-minute walk test (6MWT), completed the Generalised Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD-7), and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Measurements were repeated on completion of the programme.

Over two years, 77 patients were invited to join the programme. Twenty-two patients (28.5%) declined participation prior to initial assessment and 22 (28.5%) accepted and attended the initial assessment, but subsequently withdrew from the programme. In total, 33 patients completed the entire programme (63.9 ± 1.7 years, 58% female). On completion, patients covered longer distances during the 6MWT, had lower GAD-7 scores, and lower PHQ-9 scores, compared with their baseline results. Compared with patients that completed the entire programme, those who withdrew from the study had, at baseline, a significantly higher body mass index (BMI), covered a shorter distance during the 6MWT, and had higher PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores.

In conclusion, enrolling patients with AF into an NHS cardiac rehabilitation programme is feasible, with nearly half of those invited completing the programme. In this feasibility study, cardiac rehabilitation resulted in an improved 6MWT, and reduced anxiety and depression levels, in the short term. Severe obesity, higher anxiety and depression levels, and lower initial exercise capacity appear to be barriers to completing exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation. These results warrant further investigation in larger cohorts.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac rhythm disturbance in adults, estimated to affect 3.29% of the population in the UK in 2016.1 The condition is strongly associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, in addition to reduced quality of life.2 The healthcare costs of managing patients with AF are high: estimates of the direct cost in Western Europe range from €450 to €3,000 per patient-year.3

Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation is an established intervention in the management of several cardiovascular conditions, including coronary artery disease4 and heart failure.5 There is increasing recognition for the role of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in the management of patients with AF, with recent studies suggesting that it can result in improvements in exercise capacity, health-related quality of life, symptom burden, and cardiac function, compared with a no-exercise control.6 Despite this, exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation has not yet been routinely taken up in the management of AF within the National Health Service (NHS).

The recent launch of the NHS Long Term Plan has placed particular emphasis on efficient use of funds and services, and improvement of out-of-hospital care. With this in mind, we aimed to develop an improved pathway for patients with AF within our institution, all the while utilising existing services so as to minimise additional costs.

The initial aim of this project was to assess the feasibility of utilising an established NHS cardiac rehabilitation programme in the management of AF. Next, we aimed to examine the effects of this intervention on exercise capacity, weight, and psychological health. Finally, we aimed to identify factors that might lead patients to withdraw from the programme, in order to target these factors in the future.

Materials and method

Between 17 April 2016 and 13 July 2018, 77 symptomatic patients with AF (paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent) attending the cardiology outpatient clinic at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust were invited to participate in an established six-week phase 3 cardiac rehabilitation programme.

Table 1. Demographics and characteristics of patients completing phase 3 cardiac rehabilitation

| Total number of patients | 33 |

|---|---|

| Mean age, years | 69.9 ± 1.7 |

| Female, n (%) | 19 (58%) |

| Atrial fibrillation type, n (%) Paroxysmal Persistent Permanent |

15 (45.5%) 16 (48.5%) 2 (6%) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 20 (60%) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia, n (%) | 14 (42%) |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 5 (15%) |

| Ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | 5 (15%) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 5 (15%) |

| Obstructive sleep apnoea, n (%) | 4 (12%) |

| Previous ablation for AF, n (%) Catheter ablation Surgical ablation |

5 (15%) 4 (12%) 1 (3%) |

| Medications, n (%) Beta blocker Digoxin ACE inhibitor Angiotensin-receptor antagonist Anti-arrhythmic therapy Warfarin Direct oral anticoagulant Not anticoagulated |

27 (82%) 2 (6%) 10 (30%) 5 (15%) 14 (42%) 6 (18%) 26 (79%) 1 (3%) |

| Transthoracic echocardiogram measurements | |

| Left ventricular systolic function, n (%) Preserved Mild LVSD Moderate LVSD Severe LVSD |

28 (85%) 2 (6%) 2 (6%) 1 (3%) |

| Valvular disease, n (%) Moderate MR Moderate AS |

4 (12%) 1 (3%) |

| Left atrial size, cm | 5.1 ± 1.8 |

| Key: ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; AF = atrial fibrillation; AS = aortic stenosis; LVSD = left ventricular systolic dysfunction; MR = mitral regurgitation | |

The programme was composed of physical activity sessions (two sessions per week: one gym-based, one circuit-based) and education sessions (one session per week, covering advice on diet, exercise, risk factor modification, cardiopulmonary resuscitation and stress management, in addition to basic cardiovascular anatomy and physiology). At the start of the programme, patients were weighed and had their height measured, had their heart rate (HR) and blood pressure (BP) recorded, performed the six-minute walk test (6MWT), completed the Generalised Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD-7; scoring 0–21, higher scores indicating higher anxiety levels), and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; scoring 0–27, higher scores indicating higher depression levels). On completion of the programme, all measurements were repeated, and patients were given the opportunity to continue exercising in a structured and supervised environment with one of the physical activity referral instructors (phase 4 referral). Ethical approval was not sought for this study as this was a service evaluation study.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 24. Normality of distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Paired continuous data were compared with paired t-test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test, as appropriate. Unpaired continuous data were compared with independent sample t-test or Mann-Whitney U-tests, as appropriate. Tests were two-tailed: p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

Of the 77 patients invited to join the programme, 22 patients (28.5%) declined participation prior to initial assessment and 22 (28.5%) accepted and attended the initial assessment, but subsequently failed to attend the programme. In total, 33 patients (43%) completed the entire programme (63.9 ± 1.7 years, 58% female, body mass index [BMI] 33.9 ± 1.3 kg/m2, mean left atrial size 5.1 ± 0.2 cm). Patient recruitment and flow is summarised in figure 1. Baseline demographics of the patients who completed the entire programme are summarised in table 1.

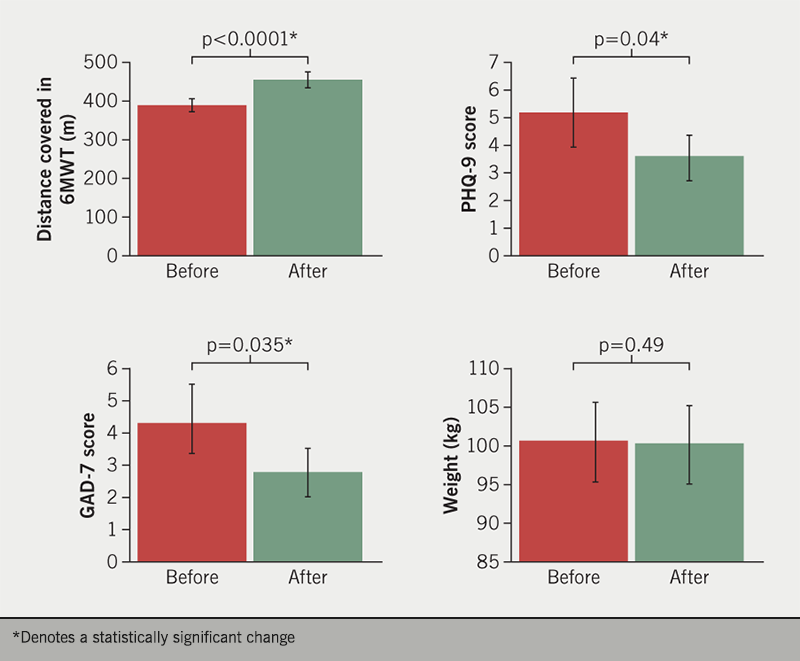

On completion of the programme, enrolled patients covered longer distances during the 6MWT (389.5 ± 12.2 vs. 447.9 ± 14.1 metres, p<0.0001; a 15% improvement), had lower GAD-7 scores (4.12 ± 1.2 vs. 2.65 ± 0.7, p=0.035), and lower PHQ-9 scores (5.0 ± 1.2 vs. 3.42 ± 0.8, p=0.04) (figure 2). Patient weight was unchanged on completing cardiac rehabilitation (102.1 ± 4.4 vs. 101.6 ± 4.4 kg, p=0.49), as was resting heart rate (73.5 ± 2.2 vs. 75.3 ± 2.4 bpm, p=0.37), and resting systolic blood pressure (129.9 ± 2.9 vs. 128.6 ± 3.6 mmHg, p=0.69). Of the 33 who completed the programme, 23 (70%) proceeded to a phase 4 referral.

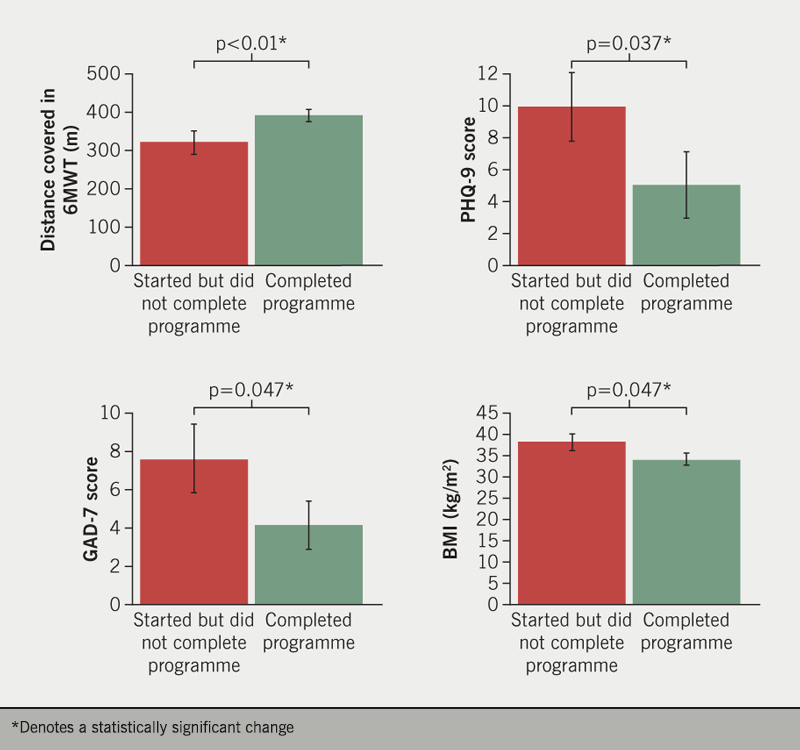

Compared with patients that completed the entire programme, those who attended the initial assessment but failed to complete the programme (n=22) had significantly higher weight and BMI (respectively, 115.6 ± 7.2 vs. 102.1 ± 4.4 kg, p=0.047; 37.9 ± 2.1 vs. 33.9 ± 1.5 kg/m2, p=0.047), covered a shorter distance during the 6MWT (318.8 ± 27.2 vs. 389.5 ± 12.2 m, p<0.01), had higher PHQ-9 scores (9.87 ± 2.1 vs. 5.0 ± 1.2, p=0.037), and higher GAD-7 scores (7.53 ± 1.8 vs. 4.12 ± 1.2, p=0.047) (figure 3).

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that it is feasible to utilise an established NHS cardiac rehabilitation programme in the management of patients with symptomatic AF. This intervention resulted in an improved 6MWT, and reduced anxiety and depression levels, in the short term. Barriers to completing exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in our study included severe obesity, higher anxiety and depression levels, and lower initial exercise capacity.

Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation is widely recognised in the management of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD). Indeed, medium- to longer-term studies show that it is effective at reducing cardiovascular mortality in patients with CAD, while shorter-term studies show that it reduces hospitalisation.4 More recently, there has been increasing interest in the use of lifestyle modification in the management of AF. The LEGACY (Long-Term Effect of Goal-Directed Weight Management in an Atrial Fibrillation Cohort: A Long-Term Follow-Up Study) trial demonstrated that long-term sustained weight loss is associated with maintenance of sinus rhythm and significant reductions in AF symptom burden.7 In addition to this, the CARDIO-FIT (Impact of CARDIOrespiratory FITness on Arrhythmia Recurrence in Obese Individuals With Atrial Fibrillation) study found that improvement in cardiorespiratory fitness augments the beneficial effects of weight loss.8 A recent meta-analysis of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in AF concludes that this intervention results in improvements in symptom burden, exercise capacity, health-related quality of life, and cardiac function.6 However, additional high-quality and well-reported randomised trials are required to identify the effects of cardiac rehabilitation on cardiac morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs. Furthermore, as atrial fibrillation represents a heterogenous cohort of patients, the effects of the intervention on different AF subtypes are not clear.

Through our study, we first demonstrate that it is possible to utilise an existing NHS-commissioned exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation service as part of the holistic management of patients with AF. Of those invited to join, nearly half completed the six-week programme, with significant improvements in exercise capacity, anxiety scores and depression scores over this time period. Moreover, 70% of patients that completed the programme opted to continue exercising in a structured supervised environment with one of the physical activity instructors. Importantly, we did not detect a change in weight over the six-week period. Our analysis also identified specific factors that might lead to patients withdrawing from the programme. In particular, patients that attended the initial assessment but failed to complete the programme had significantly higher BMI, covered shorter distances during the 6MWT, and had higher baseline PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores. The identification of these potential barriers will allow us to implement measures targeting nutrition, weight loss, and mental health, in order to improve patient engagement. We plan to focus on these barriers in the future in order to develop a more comprehensive management programme. Specifically, in Sheffield, we plan on utilising the Sheffield IAPT (Improving Access to Psychological Therapies) service, alongside a weight management programme (Why Weight), in order to form an integrated pathway for our patients with AF.

To our knowledge, this is the first published study to examine the use of an existing NHS-funded exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation programme in patients with AF. We hope that our findings can be helpful to other NHS trusts considering the development of similar services. As this is a single-centre feasibility study, with a small analytical cohort, formal inference testing is not possible, and our results should be considered predominantly as descriptive. We present our outcomes as mean ± SEM as this may aid with sample size calculations in future studies. We acknowledge that further high-quality evidence is needed to identify the effects of cardiac rehabilitation on specified end points in patients with AF, particularly morbidity, mortality and cost-effectiveness. We believe that our study demonstrates that the current NHS infrastructure, with appropriate resource distribution, can accommodate a more comprehensive and cost-effective management of this increasingly common and costly (to person and society) arrhythmia.

Conclusion

At present, exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation is not recommended for patients with AF within the NHS. However, our feasibility study illustrates the potential value of this intervention. We have demonstrated that there is a willingness among patients and clinicians for a cardiac rehabilitation service, as part of an integrated service for managing AF, and that this intervention may result in improvements in exercise capacity and psychological well-being, supporting evidence from studies outside of the NHS. Our study also identified potential factors that might prevent patients with AF from taking part in an exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation programme, including severe obesity, low baseline exercise capacity, and higher anxiety and depression levels. These factors should be taken into consideration during the development of further large-scale studies assessing the impact of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation on morbidity and mortality in patients with AF within the NHS.

Key messages

- Previous studies have demonstrated that exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) results in improvements in symptom burden, exercise capacity, health-related quality of life, and cardiac function

- We demonstrate that it is feasible to utilise an established NHS cardiac rehabilitation programme in the management of patients with symptomatic AF

- Cardiac rehabilitation in AF may result in improved exercise capacity, and reduced anxiety and depression levels, in the short term

- Barriers to completing exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation may include severe obesity, higher anxiety and depression levels, and lower initial exercise capacity

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Study approval

Ethical approval was not sought for this study as this was a service evaluation study.

References

1. Adderley NJ, Ryan R, Nirantharakumar K, Marshall T. Prevalence and treatment of atrial fibrillation in UK general practice from 2000 to 2016. Heart 2019;105:27–33. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2018-312977

2. Chugh SS, Havmoeller R, Narayanan K et al. Worldwide epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: a Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Circulation 2014;129:837–47. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005119

3. Wolowacz SE, Samuel M, Brennan VK, Jasso-Mosqueda JG, Van Gelder IC. The cost of illness of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review of the recent literature. Europace 2011;13:1375–85. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eur194

4. Heran BS, Chen JM, Ebrahim S et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(7):CD001800. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001800.pub2

5. Shah NP, AbuHaniyeh A, Ahmed H. Cardiac rehabilitation: current review of the literature and its role in patients with heart failure. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 2018;20:12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-018-0611-5

6. Smart NA, King N, Lambert JD et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation improves exercise capacity and health-related quality of life in people with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised and non-randomised trials. Open Heart 2018;5:e000880. https://doi.org/10.1136/openhrt-2018-000880

7. Pathak RK, Middeldorp ME, Meredith M et al. Long-term effect of goal-directed weight management in an atrial fibrillation cohort: a long-term follow-up study (LEGACY). J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:2159–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.002

8. Pathak RK, Elliott A, Middeldorp ME et al. Impact of CARDIOrespiratory FITness on arrhythmia recurrence in obese individuals with atrial fibrillation: the CARDIO-FIT study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:985–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.488