Wellens’ syndrome, characterised by specific T-wave changes on electrocardiogram (ECG), indicates critical proximal left anterior descending (LAD) stenosis and high acute myocardial infarction risk. While revascularisation is the standard treatment, it may be unsuitable for elderly patients with comorbidities. We present a case of successful medical management of Wellens’ syndrome type B in a 94-year-old woman deemed unfit for invasive interventions. The patient was treated with dual antiplatelet therapy, high-intensity statin, and anti-anginal medications. Symptom control was achieved, and serial ECGs and cardiac biomarkers remained stable. This case demonstrates that aggressive medical management can be a viable alternative in elderly patients with Wellens’ syndrome type B, unsuitable for invasive procedures.

Introduction

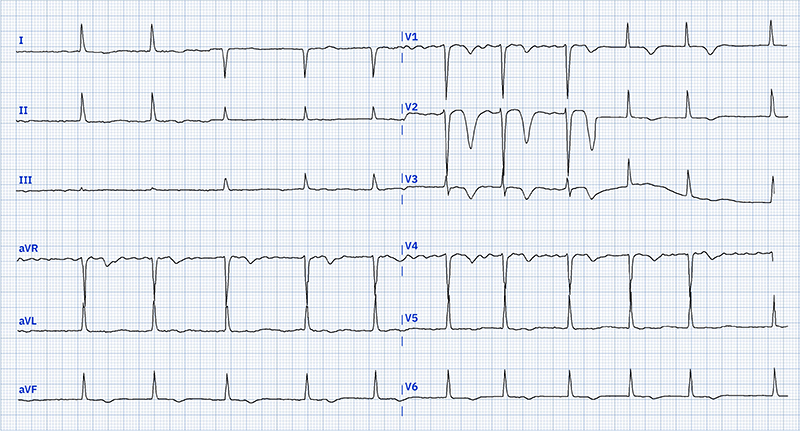

Wellens’ syndrome is a pre-infarction electrocardiogram (ECG) pattern indicating critical proximal left anterior descending (LAD) stenosis and high risk of imminent acute myocardial infarction (MI). It is characterised by specific T-wave changes in precordial leads, typically biphasic or deeply inverted T-waves in V2–V3 (type B) or symmetrical deeply inverted T-waves in V1–V6 (type A).1 This pre-infarction state represents temporary stabilisation of an unstable coronary plaque.2

Current guidelines recommend urgent coronary angiography and revascularisation. However, for elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, invasive interventions may pose higher risks than benefits, including contrast-induced nephropathy, bleeding, stroke, and procedural complications.3,4

Case report

A 94-year-old woman presented with 10 minutes of sudden-onset central chest pain radiating to both sides of her jaw. Her medical history included atrial fibrillation, hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage III, type 2 diabetes, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), anxiety, and frailty. On arrival, the patient had mild chest discomfort with stable vital signs, except for elevated blood pressure (179/67 mmHg).

The 12-lead ECG on presentation (figure 1) showed characteristics consistent with Wellens’ syndrome type B. Admission troponin was 34.6 ng/L (reference <37 ng/L). A bedside echocardiogram revealed mild left ventricular (LV) impairment with regional wall motion abnormalities.

Considering the patient’s age, comorbidities, and risk of contrast-induced nephropathy,3,4 primary cutaneous intervention was ruled out in favour of medical management. The patient was admitted for observation, with apixaban suspended and dual antiplatelet therapy initiated (aspirin and clopidogrel). She was also started on fondaparinux and an increased dose of bisoprolol.

The patient remained asymptomatic during her three-day hospital stay. A pre-discharge echocardiogram showed improved cardiac function with LV ejection fraction (LVEF) >50%. She was discharged on lifelong single antiplatelet therapy (clopidogrel), apixaban, and an increased dose of bisoprolol.

Discussion

Wellens’ syndrome is critical, with 75–100% of patients having significant LAD stenosis and high anterior MI risk.1 While the original study recommended urgent angiography due to poor conservative outcomes, 25% of patients remained asymptomatic with medical management alone, suggesting its potential viability in select cases.5

Our decision to pursue medical management was based on the patient’s advanced age, frailty, high risk of contrast-induced nephropathy, and potential complications of invasive procedures in elderly patients.3,4

The recently published SENIOR-RITA (Older Patients with Non–ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Randomized Interventional Treatment) trial provides valuable insights into the management of older adults with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI).6 This large randomised trial found that in patients aged 75 years or older with NSTEMI, an invasive strategy did not result in a significantly lower risk of cardiovascular death or non-fatal MI compared with a conservative strategy over a median follow-up of 4.1 years.6 Notably, procedural complications occurred in less than 1% of patients, which is lower than previously reported rates in elderly populations.6,7

While our patient had Wellens’ syndrome, the SENIOR-RITA results support a conservative approach in high-risk elderly patients with acute coronary syndromes. However, the trial’s lower non-fatal MI risk with invasive strategy highlights important considerations. When opting for medical management, clinicians should emphasise careful patient selection, ensure close follow-up, and thoroughly evaluate potential long-term outcomes.6,7

Our case, like Coutinho et al.’s report,8 demonstrates successful medical management of Wellens’ syndrome in an elderly patient. It suggests medical therapy as a viable alternative for symptomatic elderly patients with Wellens’ pattern B when invasive-procedure risks outweigh benefits.

However, this case report is limited by its single-patient focus and lack of long-term follow-up data. Larger studies are needed to establish the safety and efficacy of conservative management in elderly patients with Wellens’ syndrome.

Key messages

- Individualised care is crucial in complex cases of Wellens’ syndrome, especially for frail elderly patients with high procedural risks

- Carefully monitored medical management can be a reasonable alternative to revascularisation in select high-risk patients

- The SENIOR-RITA trial results support considering a conservative approach in elderly patients with acute coronary syndromes, but careful patient selection and close follow-up are essential

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Patient consent

Written consent has been obtained from the patient for publication of the details of their medical case and the accompanying images.

References

1. Hsu YC, Hsu CW, Chen TC. Type B Wellens’ syndrome: electrocardiogram patterns that clinicians should be aware of. Tzu Chi Med J 2017;29:127–8. https://doi.org/10.4103/tcmj.tcmj_26_17

2. Mathew R, Zhang Y, Izzo C, Reddy P. Wellens’ syndrome: a sign of impending myocardial infarction. Cureus 2022;14:e26084. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.26084

3. Mehran R, Aymong ED, Nikolsky E et al. A simple risk score for prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary intervention: development and initial validation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;44:1393–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2004.06.068

4. Mohammed NM, Mahfouz A, Achkar K, Rafie IM, Hajar R. Contrast-induced nephropathy. Heart Views 2013;14:106–16. https://doi.org/10.4103/1995-705X.125926

5. de Zwaan C, Bär FW, Wellens HJ. Characteristic electrocardiographic pattern indicating a critical stenosis high in left anterior descending coronary artery in patients admitted because of impending myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 1982;103(4 Pt 2):730–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-8703(82)90480-X

6. Kunadian V, Mossop H, Shields C et al. Invasive treatment strategy for older patients with myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2024;391:1673–84. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2407791

7. Berg ES, Tegn NK, Abdelnoor M et al. Long-term outcomes of invasive vs conservative strategies for older patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023;82:2021–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2023.09.809

8. Coutinho Cruz M, Luiz I, Ferreira L, Cruz Ferreira R. Wellens’ syndrome: a bad omen. Cardiology 2017;137:100–03. https://doi.org/10.1159/000455911