The number of patients with aortic stenosis (AS) in the UK is increasing. Patients with non-significant AS can be safely reviewed in technician-led clinics. The potential impact of this on healthcare services is unreported. The aim of this study was to describe the impact of establishing an AS surveillance clinic in a district general hospital setting and consider the potential impact of widespread implementation.

Criteria for an AS surveillance clinic were developed. Patients who were deemed suitable were identified from existing echocardiographic databases, discharge coding and review of the clinical notes. Patients with AS were identified (n=612). After a review of echocardiographic parameters, 117 patients were considered suitable for technician-led review. Of these, 47 patients (40%) were subsequently discharged from the cardiology clinic.

A small proportion of patients are reviewed in the general cardiology clinic for no other reason than asymptomatic mild AS (5% of follow-up appointments). Establishment of a national AS surveillance programme could result in a large number of patients (>9,000) being discharged from formal doctor-led cardiology clinic review in the UK. This would improve quality and consistency of follow-up monitoring for the patient and free up capacity to see new patients.

Introduction

Aortic stenosis (AS) is the most common form of valvular heart disease.1 The incidence is increasing due to an ageing population. Aortic sclerosis is present in up to 25% of adults over the age of 65 years with progression to severe AS within seven years in about 16%.2 Thus, surveillance of these patients is required. Recent guidelines suggest that patients with mild AS can be reviewed infrequently (up to every five years). Those with a higher degree of AS should be kept under more frequent review. Asymptomatic patients with mild AS make up a significant proportion of patients followed up in general out-patient cardiology clinics.3

Within the UK, demand for specialist cardiology services continues to increase. Service redesign, which allows a review of asymptomatic patients with AS without a clinic review by a doctor, could increase capacity to see new patients. This study describes the establishment of an AS surveillance clinic in a district general hospital.

Aim

To describe and discuss the potential benefits of widespread implementation of an AS surveillance clinic.

Methods

Setting

The study was performed in a Scottish district general hospital with a catchment population of around 200,000.

Identification of potential patients

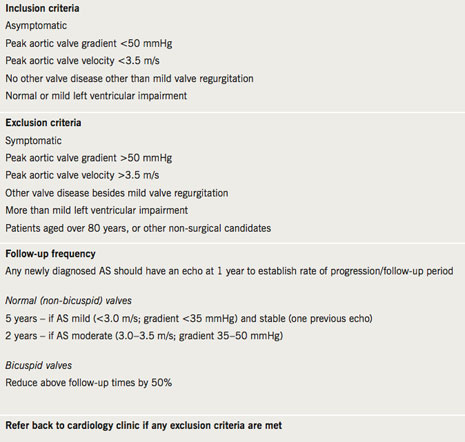

Following local discussions, review of criteria from other centres and reference to national guidelines,5 specific criteria were developed for patients who would be suitable for follow-up in a technician-led AS surveillance clinic (table 1). Patients who were potentially suitable for inclusion were identified both in a prospective and retrospective manner. Prospective opportunistic identification of patients via cardiology clinic was undertaken by informing all cardiology staff of the presence of the clinic criteria. A retrospective review was undertaken of patients who were already known to have AS. They were identified from the echocardiography database or by discharge codes following opportunistic in-patient admission using International Classification for Disease-10 (ICD-10) code (I06.0, I06.2, I08.0, I08.2, I08.3, I08.8, I35, I42.1, I08.0, Q23.0, Q23.1, I06, I35.0, I35.1, I35.2, I35.8, I35.9, I39.1, Q23.0, Q23.8) in the year 2008 (01/01/2008 to 31/12/2008). Cases identified from these two sources were cross-referenced and a final cohort identified.

Data collection

Echocardiography reports were studied from all patients in the identified cohort. These had been produced from routine 2D echo (GE vivid 7) by British Society of Echocardiography (BSE) trained cardiac sonographers. Key data were extracted (maximum AV velocity, maximum AV pressure gradient, degree of aortic regurgitation, other valve pathology, i.e. mitral regurgitation or stenosis, pulmonary regurgitation or stenosis and tricuspid regurgitation or stenosis, left ventricular systolic function and valve calcification). The criteria for inclusion in the surveillance clinic (table 1) were then applied to the cohort to identify all patients suitable for follow-up based on echocardiography findings. The medical notes of this smaller group of patients were then examined to identify those patients who may need to be excluded from the surveillance clinic because of other elements requiring medical opinion such as other co-morbidities.

AS surveillance clinic

The final cohort of identified suitable patients were advised of their inclusion in the surveillance clinic, and allocated a follow-up appointment time based on the established criteria (table 1). The clinics have been established using a routine out-patient echo session and are run jointly by a BSE accredited echocardiographer and a trained cardiac nurse. On attendance, patients are asked about existing and new symptoms and a routine echo is performed (concentrating on obtaining aortic valve surveillance data – table 2). An electronic letter is generated following each clinic visit with paper copies sent to both the consultant in charge and the general practitioner with details of the echocardiogram result and the date of the next clinic appointment as determined by protocol. Where the patient symptoms or echo findings meet the exclusion criteria, patients are referred back to the cardiologist for follow-up in cardiology clinic.

Ethics

As this was a clinical case review, ethical approval was not required.

Results

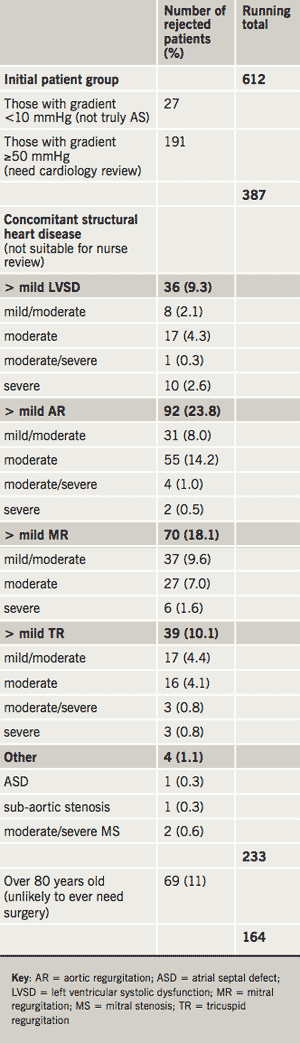

Of 723 patients initially identified, 113 (16%) were rejected (88 had a prosthetic aortic valve, five were miscoded as AS and data were missing on 23 patients). Thus, 612 patients with AS were identified. The agreed surveillance clinic referral criteria were then applied to this cohort. The numbers rejected for each element of the criteria (n=448), such as left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD) or concomitant valve disease that was more than mild in severity, are detailed in table 2. Of the remaining 164 patients, clinical notes were available for 142 (88%).

Following review of the available clinical notes 37 (35%) of these patients were deemed not suitable for the clinic for the following reasons: dead (n=4), frail or significant co-morbidities (n=12), other significant valve disease (n=8), miscoded (n=10), other (n=3). This left 105 (74%) patients identified from the retrospective analysis as suitable for the AS surveillance clinic. An additional 12 patients (not identified by the above process) were prospectively identified in the cardiology clinic and, thus, in total, 117 patients were initially entered into the AS surveillance clinic. Of these, 47 (40%) patients were specifically attending the cardiology clinic for review of their asymptomatic AS. They were contacted by letter, enrolled in the AS surveillance clinic and their cardiology clinic review was cancelled.

Discussion

Patients with asymptomatic valve lesions, in particular AS, are reviewed in a variety of clinics, including general medicine and general cardiology. Echocardiography is arranged at the request of the physician/cardiologist. Thus, patients may have to attend both for echocardiography and clinic review. The often ad hoc request of echocardiography may result in the frequency of echocardiographic monitoring not being correct. This may result in a waste of valuable echocardiographic resource or increased risk to the patient. Even in centres that deliver a comprehensive ‘one-stop’ service, review by a doctor is not necessary in the majority of patients with asymptomatic AS.

This current study identified a cohort of patients (n=117) who did not need to be reviewed in a cardiology clinic. While the number of clinic appointments that were cancelled was relatively small, these are recurrent annual or two-yearly appointments and, therefore, the cumulative impact of this small change in clinical practice is significant, representing about 5% of review clinic appointments. Furthermore, due to the limited date range interrogated, we estimate that the above methodology identified approximately 50% of suitable patients. Given that the catchment population of our hospital represents approximately 4% of Scotland and 0.4% of the UK populations then extrapolation of these data suggests that in excess of 900 patients in Scotland could immediately be removed from cardiology clinic and >9,000 in the UK by employing our methodology. These would represent recurrent savings and are likely to underestimate the actual benefit that could be realised over time. Furthermore, as confidence grows with technician-led clinics it is likely that these clinics could be used to monitor other valvular lesions or patients with valve replacement. This could greatly increase the efficacy and clinical impact of this approach to valve disease management.

The presence of patients with various grades of AS is of value for the teaching of junior staff and medical students, and, clearly, the creation of aortic valve surveillance clinics would reduce the number of patients with murmurs in the general cardiology clinic. However, these patients will still attend hospital for echocardiography and nurse review and thus an aortic valve surveillance clinic could itself be a valuable teaching resource.

The object of this study was to identify patients who may benefit from a more systematic approach to the clinical care of their asymptomatic AS. The use of a structured specialist clinic should ensure that these patients receive evidence-based care and are not inadvertently ‘lost to follow-up’ (over 50% of our identified cohort were patients with AS who had not been scheduled for follow-up). Results from other centres show that this approach is sustainable and reduces the routine use of echocardiography5 and, thus, should result in increased capacity with no increased cost. Moreover, patients will likely have fewer journeys to hospital reducing costs for patients and healthcare providers. This may be particularly important for patients in remote areas. Notably, a reduction in carbon footprint is now a key target for the National Health Service (NHS).

Conclusions

The establishment of an AS surveillance clinic has resulted in a modest reduction in patients attending the cardiology out-patient department. This new system is more clinically efficient and is also likely to be cost-effective, as it negates the need for formal cardiology clinic review, saves consultant time, standardises care and potentially reduces the number of echocardiograms requested. Widespread national implementation of such clinics should be considered. Given current resource constraints, the ability to redesign services to optimise the contribution of consultant cardiologists has obvious benefits. Although impacts, in isolation, are modest, clinical leaders and managers need to encourage all departments to make improvements and refinements so that collective benefits for the organisation (NHS) and patients are realised •

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr Gethin Ellis for discussions and suggestions regarding aortic valve surveillance clinic criterion.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Key messages

- The number of patients with aortic stenosis in the UK is increasing

- Demand for specialist cardiology assessment is increasing

- An AS surveillance clinic can result in a modest reduction in patients attending the cardiology out-patient department

- Widespread national implementation of such clinics should be considered

References

- Lindroos M, Kupari M, Heikkilä J, Tilvis R. Prevalence of aortic valve abnormalities in the elderly: an echocardiographic study of a random population sample. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993;21:1220–5.

- Otto CM. Aortic stenosis: even mild disease is significant. Eur Heart J 2004;25:185–90.

- Hughes ML, Leslie SJ, McInnes GK, McCormac K, Peden NR. Can we see more outpatients without more doctors? J Royal Soc Med 2003;96:333–7.

- Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Kanu C et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Thoracic Surgeons. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease): developed in collaboration with the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists: endorsed by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 2006;114:e84–e231.

- Taggu W, Topham A, Hart L et al. A cardiac sonographer led follow up clinic for heart valve disease. Int J Cardiol 2009;132:240–3.