Balloon aortic valvuloplasty (BAV), first developed last century for the management of symptomatic aortic stenosis, was met with great enthusiasm due to its new and minimally invasive technique, but it has now largely been abandoned due to suboptimal results and a high restenosis rate. However, with the development of new techniques and the arrival of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), BAV’s use is starting to increase. In this article we put forward the case for a revival in BAV by exploring the traditional uses and safety of BAV as a procedure as well as a novel role as a bridge to TAVI.

Introduction

Balloon aortic valvuloplasty (BAV) was first developed by Alain Cribier over 30 years ago for the management of aortic stenosis (AS).1 It was initially met with great enthusiasm due to its minimally invasive nature and possible alternative to surgery, but later fell from grace due mainly to high restenosis and complication rates. In addition, suboptimal results were obtained when compared with surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR).2 However, the evolution of techniques and devices culminating in transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has drastically shifted the treatment options for high-risk patients with severe AS.

TAVI is a rapidly developing procedure, with which extensive criteria exist for assessing suitability.3 BAV is used during TAVI to increase the orifice area of the native valve pre-implantation of the stent-based valve. TAVI has reinvigorated the use of BAV by interventional cardiologists as a means of improving symptoms, bridging patients to eventual SAVR, or as part of the TAVI procedure. A revival in the use of BAV is warranted in selected patients for the management of symptomatic AS.

History

The two main registries used last century to evaluate BAV were the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the Mansfield Scientific.4,5 The registries contained several hundred patients (674 vs. 492) of which many were non-surgical. The results showed that BAV improved both aortic valve area and haemodynamic status significantly, however, when compared with surgery the results were inferior. In addition, the complication rates were high (>20%), the most common of which was bleeding from the femoral artery site. Less common complications included stroke, emboli and ventricular perforation. Furthermore, BAV had no real effect on mortality when compared with the natural history of patients with symptomatic AS,6,7 and the restenosis rate was unacceptably high (approximately 80% in 15 months).8 These factors culminated in the decline of BAV, and to date BAV has largely been abandoned in most centres.

Method

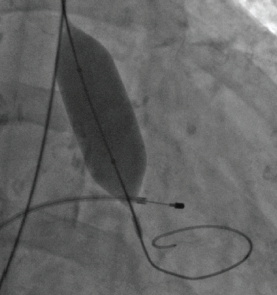

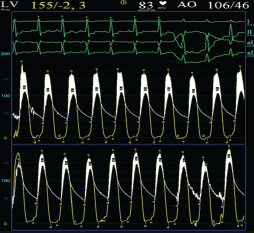

BAV is an interventional procedure that involves the inflation of a balloon across a stenotic valve, thereby increasing the orifice area. The exact mechanism by which the orifice is increased is, however, unknown.2 The retrograde approach is the main approach used, involving the femoral artery and the positioning of a guide wire across the valve from the aorta and inflation of the balloon afterwards (figure 1). Early techniques involved large catheters and guide wires leading to greater complications, which included strokes and bleeding from the femoral puncture site. The introduction of smaller catheters (10–12F) and vascular closure devices have reduced these complications. In addition, rapid ventricular pacing, a technique where the ventricle is paced rapidly between 180 bpm and 220 bpm arresting the ventricle temporarily to enable the balloon to be inflated quicker and less often, as well as preventing the dislodgement of the balloon from the orifice of the valve, has further reduced complications (figure 2).9

Current guidelines

Current guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) state that BAV has Class IIb recommendations in patients who are haemodynamically unstable as a bridge to surgery or in patients with severe symptomatic AS who require urgent major non-cardiac surgery, but state that BAV could only be considered in non-surgical candidates as a palliative measure.10 Similar guidelines exist from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA), but an additional Class IIb recommendation exists as a palliative measure in non-surgical patients with AS.11

BAV as a bridge to TAVI

At present no guidelines exist regarding BAV as a bridge to TAVI. Registry data indicate TAVI to be a safe procedure for high-risk patients, including octogenarian and nonagenarian patients with severe AS.12 There are a number of clinical, anatomical and device restrictions that may deem some patients temporarily or permanently unsuitable for TAVI. In some cases BAV can be used as a bridging procedure to eventual TAVI. Although significant questions remain regarding bridging BAV to TAVI, the technique has provided another therapeutic option in high-risk patients.13,14

Australian series

In the last five years at three major centres in Melbourne, 51 cases (22 males, 29 females) of mean age 82 (26–97) years have undergone BAV, with a large proportion of our cohort being acquired in the last year due to the arrival of TAVI. All were non-surgical candidates, with contraindications ranging from severe heart failure, redo surgery, porcelain aorta, refusal of surgery, advanced age, frailty, sepsis, and malignancy. Femoral artery access was used with 10–12F sheaths in all cases and balloon sizes varied from 18 mm to 25 mm. In addition, rapid ventricular pacing was used and vascular closure devices such as PROSTAR XLTM (AbbottCorp, Redwood City, CA, USA) utilised for haemostasis.

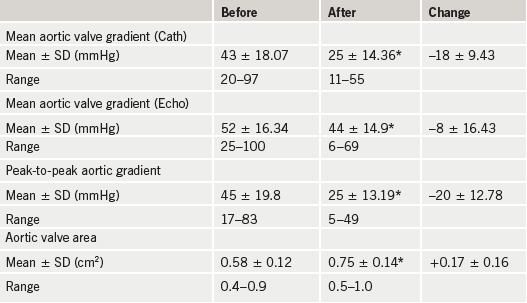

Our results show that the mean aortic pressure gradient fell from 52 to 44 mmHg (p<0.05) when determined by echocardiography, and 43 to 25 mmHg (p<0.05) during catheterisation. The peak-to-peak gradient fell from 45 to 25 mmHg (p<0.05), and aortic valve area increased from 0.58 to 0.75 cm2 as determined by echocardiography (p<0.05) (table 1). Although these benefits are modest, the symptomatic benefit is what is most striking in the series with 100% of surviving patients in New York Heart Association (NYHA) I/II at time of discharge. Three repeat procedures were used at an average of six months after the first valvuloplasty due to a return of symptoms. Procedural mortality was 2% (n=1), and survival to discharge was 92%. One death was attributable to retroperitoneal bleeding and co-morbidities. The remaining causes of death were unrelated to the procedure and included sepsis, renal failure, intractable heart failure and pneumonia. Non-fatal complications (10%) were related to the site of entry of the femoral sheath. Surgery was required in two cases (4%), involving closure of the femoral artery and correction of an arteriovenous fistula. Of note, no strokes were suffered by any of the patients. An important point of our experience is that with the arrival of TAVI and the use of BAV as a prerequisite to implantation, our complication rates have reduced with only one complication of minor bleeding occurring in the most recent 30 patients of our dataset. This suggests that in our experience, when the use of TAVI proliferates, the procedure will facilitate interventional cardiologists being able to perform BAV with a very low complication rate.

Clinical case

An 80-year-old woman presented for pre-operative assessment before hysterectomy for uterine cancer. She had no history of cardiac disease but described mild NYHA II heart failure symptoms. An echocardiogram revealed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 60% with severe AS; mean pressure gradient 50 mmHg and aortic valve area of 0.6 cm2.

The patient did not wish to undergo open SAVR. The patient was offered BAV to which she and her family consented. A retrograde approach with a 20 mm balloon was used. One inflation was performed across the aortic valve during simultaneous rapid ventricular pacing at 220 bpm. The post-valvuloplasty mean gradient was reduced to 25 mmHg, and the aortic valve area increased to 0.95 cm2 (figure 3). The patient underwent uncomplicated hysterectomy and salpingo-oopherectomy for stage 1a uterine cancer. Four months later, recovered from her laparotomy, the patient again refused open SAVR. She, therefore, underwent retrograde percutaneous aortic valve replacement with a 26 mm CoreValve without complication. Three months post-procedure the patient is NYHA I. An echocardiogram revealed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 70% and a well-seated CoreValve with mean aortic pressure gradient of 6 mmHg and aortic valve area of 2.3 cm2.

Discussion

In an era of TAVI, the option of ‘medical management’ for very high-risk or elderly patients with severe AS has decreasing clinical utility. With careful case selection and evolving techniques, BAV has an important role in non-surgical candidates with AS. Whether it is as a bridge to SAVR or TAVI, part of the TAVI procedure or merely to improve symptoms, BAV will have an increasing role in managing severe AS.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Key messages

- Until recently, balloon aortic valvuloplasty (BAV) has had limited clinical utility due to high restenosis and complication rates

- BAV can be performed safely and effectively as the procedure has evolved

- BAV can be used as a bridge to transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI)

References

1. Cribier A, Savin T, Saoudi N, Rocha P, Berland J, Letac B. Percutaneous transluminal valvuloplasty of acquired aortic stenosis in elderly patients: an alternative to valve replacement? Lancet 1986;327:63–7.

2. Hara H, Pedersen WR, Ladich E et al. Percutaneous balloon aortic valvuloplasty revisited: time for a renaissance? Circulation 2007;115:e334–e338.

3. Vahanian A, Alfieri OR, Al-Attar N et al. Transcatheter valve implantation for patients with aortic stenosis: a position statement from the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), in collaboration with the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008;34:1–8.

4. Registry NHLBI. Percutaneous balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Acute and 30-day follow up results in 674 patients from the NHLBI Balloon Valvuloplasty Registry. Circulation 1991;84:2383–97.

5. McKay RG. The Mansfield Scientific Aortic Valvuloplasty Registry: overview of acute haemodynamic results and procedural complications. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991;17:485–91.

6. O’Keefe JH Jr, Vlietstra RE, Bailey KR, Holmes DR Jr. Natural history of candidates for balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Mayo Clin Proc 1987;62:986–91.

7. Otto CM, Mickel MC, Kennedy JW et al. Three year outcome after balloon aortic balloon valvuloplasty: insights into prognosis of valvular aortic stenosis. Circulation 1994;89:642–50.

8. Letac B, Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Koning R, Derumeaux G. Evaluation of restenosis after balloon dilatation in adult aortic stenosis by repeat catheterization. Am Heart J 1991;122(1 Pt 1):55–60.

9. Davidson MJ, Baim DS. Percutaneous aortic valve interventions. In: Cohn LH, ed. Cardiac surgery in the adult. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008;963–71.

10. Vahanian A, Baumgartner H, Bax J et al. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease. The Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2007;28:230–68.

11. Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K et al. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to revise the 1998 guidelines for the Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease): Developed in collaboration with the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists: endorsed by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 2006;114:e84–e231.

12. Rodés-Cabau J, Webb JG, Cheung A et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation for the treatment of severe symptomatic aortic stenosis in patients at very high or prohibitive surgical risk: acute and late outcomes of the multicenter Canadian experience. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:1080–90.

13. Descoutures F, Himbert D, Lepage L et al. Contemporary surgical or percuatenous management of severe aortic stenosis. Eur Heart J 2008;29:1410–17.

14. Agiatello C, Eltchaninoff H, Tron C et al. Balloon aortic valvuloplasty in the adult. Immediate results and in-hospital complications in the latest series of 141 consecutive patients at the University Hospital of Rouen (2002–2005). Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss 2006;99:195–200.