Most people do not wish to die in hospital, yet most people do. Patients with chronic heart failure (CHF) appear to be particularly disadvantaged in this regard, partly because it can be difficult to recognise when the issue should be broached. This review by two integrated cardiology–palliative care services of 235 CHF deaths, shows that only about a third of patients died in an acute hospital bed. End-of-life discussions were possible, with the majority of patients given the opportunity to express a preferred place of dying achieving their wish.

Introduction

End-of-life care is now a Department of Health (DoH) priority. Primary care trusts have been charged with ensuring provision of high-quality end-of-life care, utilising enhanced central funding.1 While most people would prefer not to die in hospital, many still do.2 In order to change this situation, clinicians need to establish individual patient’s preferences regarding place of death (PPD) and then work proactively towards their achievement. The DoH is promoting the use of tools to help with this, such as the Gold Standards Framework (GSF), Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP) and Preferred Place of Care Plan, all of which are applicable to patients with congestive heart failure (CHF).3-5

Patients dying from cancer have greater access to supportive services and consideration of their wishes in the dying phase than CHF patients,6 although more deaths in the UK are due to cardiovascular disease (36% of all deaths in 2005) than malignancy (27% of deaths).7 However, the tide is turning. Heart Failure Nurse Specialists (HFNSs) can play a valuable role in addressing end-of-life issues, as well as in monitoring/titrating cardiac medication. Collaborations between cardiology, palliative and primary care services are evolving, with HFNSs as key professionals. In an audit of just over 40 CHF deaths in Gloucester, clinicians discussed preferences of care and PPD with a third of patients. Half died at home and, of those where PPD was known, PPD was realised in 70%.8 However, discussions regarding disease progression, aim of care, and recognition of the last few days of life remain major challenges for clinicians and many are concerned about ‘taking away hope’. These fears are legitimate, though there is evidence from renal medicine and oncology that such discussions are appreciated by patients.9-11 Sensitive exploration of the patient’s own understanding, relevant information giving and discussion of possible options is key, rather than a blanket approach; “I have to tell every patient they’re going to die”.

A frequently cited obstacle to these conversations is the unpredictable disease trajectory in end-organ failure compared with the cancer patient’s more predictable deterioration.12 In practice, however, the differences are not so clear-cut. Many cancer patients follow a trajectory of slow decline interspersed with improvements and setbacks, and that of CHF may be even more chaotic than already suggested.13 UK oncology is adopting problem-based triggers for advance care planning and specialist palliative care (SPC) involvement, rather than relying solely on (often inaccurate) estimates of short-term prognosis. By getting away from the misperception that palliation is only for the imminently dying, it is also possible to improve the care of CHF patients, allowing discussion and preparation of PPD.

Two areas have developed close working partnerships between their HFNSs and SPC services. In the Scarborough area, two HFNSs manage 153 new referrals a year from a population of 160,000 in a predominantly rural area. Two community hospitals with SPC supported beds, a 16-bedded SPC hospice and nursing homes provide alternative in-patient beds to those in the district general hospital. In Bradford, six HFNSs manage 250 new referrals per year from a population of 395,000 in a predominantly urban area. Palliative care beds are provided in an 18-bedded SPC hospice and designated nursing homes. Hospice-at-home and Marie Curie nurses supplement district nursing care for those wishing to die at home. We present a review of 235 deaths of patients on the HFNSs’ caseloads.

Methods

Scarborough/Whitby/Ryedale (SWR). HFNS records of consecutive deaths between 2005 and 2008 were reviewed regarding: documented evidence of advanced planning discussions (“if things got seriously worse…”) and PPD (documented and/or HFNS recall), actual place of death and mode of death.

Bradford. HFNS case records of consecutive deaths during 12 months between 2006 and 2007 were reviewed regarding: documented PPD, actual place of death and mode of death.

Results

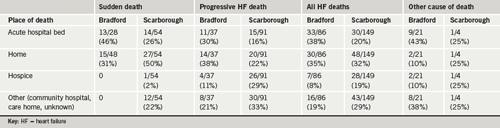

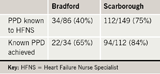

There were 149 deaths from SWR and 86 from Bradford. About one-third of patients died in an acute hospital bed and a third died in their own homes. Place and mode of death are shown in table 1 and the achievement of known PPD is shown in table 2. For SWR patients, there was evidence of advanced planning discussions in 112/149 case records and PPD was either documented or recalled by the HFNS for all these. The Bradford team had documented PPD for 34/86 patients. SPC was involved to a varying extent in 45/149 (30%) of all deaths in SWR, and 28/86 (33%) in Bradford.

Discussion

Although the methods used to review each service were slightly different (both are now prospectively collecting a common dataset), we feel the data are usefully presented together. Both services achieved a high percentage of patients dying from progressive CHF in community settings. We think this is because discussions about advanced planning, including PPD, were possible in a significant number of patients. Importantly, these discussions were mostly conducted by HFNSs, although support and training from SPC staff, experienced in such conversations, was valued. Only a third of patients needed direct SPC input, which should reassure SPC services who fear they may be expected to provide all end-of-life care for all manner of diseases. It is also noteworthy that the HFNSs in both services were strongly linked to secondary and primary care. We believe this to be crucial in allowing them to remain closely involved in care until the time of death.

Most patients died in the place of their choice, where this was known, preventing inappropriate hospital admissions, emergency ambulance use and futile attempts at cardio-pulmonary resuscitation. In both services, even where it was not possible to discharge a patient from hospital, those dying from progressive CHF were recognised and cared for using the LCP. As expected, some patients died suddenly, but it was often possible to discuss end-of-life care during their illness, allowing an opportunity to set affairs in order and to save relatives calling an emergency ambulance.

Conclusions

Recognition of advanced disease and the dying phase is often possible in CHF despite the challenges. Joint working between cardiology, primary and palliative care services coupled with courageous and skilful communication with patients nearing the end of their lives allows patient choice.

Acknowledgement

Grateful thanks to Debbie Gibbon and Mary Crawshaw-Ralli (Bradford HFNSs) and Angela Garton (SWR HFN secretary) for contributing to data collection. This audit was carried out within existing service resources.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Key messages

- Most people want to die at home, but most people still die in hospital

- Patients with chronic heart failure appear to have less understanding and choice regarding end-of-life care

- Sensitive and skilful communication between staff, patient and carer is required to discuss future management plans in the event of worsening disease

- Joint working between primary, secondary and specialist palliative care can help patients achieve their preference for place of death

References

- Darzi Report. High quality care for all: NHS next stage review final report. London: Department of Health, publications, policy and guidance, 2008. Available from:http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/publicationsandstatistics/publications/publicationspolicyandguidance/DH_085825 [accessed November 2008].

- Department of Health. End of life care strategy – promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life. London: DoH, July 2008. Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Healthcare/IntegratedCare/Endoflifecare/index.htm[accessed November 2008].

- NHS End of Life Care Programme. Gold Standards Framework. Available from: http://www.goldstandardsframework.nhs.uk

- Lancashire & South Cumbria Cancer Network. The Preferred Place of Care Plan. Available from: http://www.cancerlancashire.org.uk/ppc.html

- The Marie Curie Palliative Care Institute Liverpool. Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying Patient. Available from: http://www.mcpcil.org.uk/liverpool_care_pathway

- Murray SA, Boyd K, Kendall M, Worth A, Benton TF, Clausen H. Dying of lung cancer or cardiac failure: prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers in the community. BMJ 2002;235:929–34.

- Data obtained from www.statistics.gov.uk [accessed December 2008].

- Moore J. Primary care heart failure service. Br J Cardiol 2008;15:6.

- Fallowfield LJ, Jenkins VA, Beveridge HA. Truth may hurt but deceit hurts more: communication in palliative care. Palliat Med 2002:16:297–303.

- Michel DM, Moss AH. Communicating prognosis in the dialysis consent process: a patient-centered, guideline-supported approach. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2005;12:196–201.

- Davison S, Simpson C. Hope and advance care planning in patients with end stage renal disease: qualitative interview study. BMJ 2006;333:886.

- Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Sheikh A. Illness trajectories in palliative care. BMJ 2005;330:1007–11.

- Gott M, Barnes S, Parker C et al. Dying trajectories in heart failure. Palliat Med 2007;21:95–9.