Neither intensive blood pressure reduction, or adding a fibrate to a statin, appear to be justified in patients with diabetes at high risk of cardiovascular disease, according to studies reported at the American College of Cardiology meeting held in Atlanta, US, in March. But more encouraging news came in the form of a new percutaneous procedure that should prevent the need for mitral valve surgery.

ACCORD/INVEST: do not aim for normal blood pressure in diabetes patients with CAD

The results of two trials comparing intensive versus more conventional blood pressure lowering in patients with diabetes at high cardiovascular risk have suggested that intensive treatment is not necessary and may be harmful in this population.

In the ACCORD BP (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes – Blood Pressure) trial, while intensive blood pressure treatment did reduce the risk of stroke, it failed to reduce the overall risk of cardiovascular events in patients and was associated with an increase in adverse events due to antihypertensive therapy.

And in the INVEST (International Verapamil SR-Trandolapril) study, tight blood pressure control was no more effective in preventing major events than standard blood pressure treatment and, in some cases, it actually appeared harmful.

ACCORD

Presenting the ACCORD results, Dr William Cushman, (Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Memphis, USA) explained that previous studies have shown that treating patients with diabetes to achieve a systolic blood pressure of less than 140 to 150 mmHg reduces cardiovascular events. The ACCORD BP trial was conducted to investigate whether it would be beneficial to reduce blood pressure even further.

In the trial, 4,733 patients with type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and either pre-existing cardiovascular disease or at high risk for developing it were randomly assigned to a target systolic blood pressure of either less than 120 mmHg or less than 140 mmHg. A wide variety of blood-pressure-lowering medications were used to achieve therapeutic goals.

During the study, systolic blood pressure levels averaged 119 mmHg in the intensive-therapy group and 134 mmHg in the standard-therapy group. After a follow-up averaging five years, there was no significant difference between the two groups in the combined rate of non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), non-fatal stroke, or cardiovascular death. However, the risk of stroke was significantly lower in the intensive-therapy group (36 vs. 62 strokes).

Serious complications that could be attributed to blood pressure lowering occurred in 77 patients in the intensive-therapy group and 30 patients in the standard-therapy group. In addition, some laboratory measures of kidney function were worse in the intensive-therapy group, but there was no difference in the rates of kidney failure.

Dr Cushman commented: “The stroke results were expected based on previous clinical trials, but we were surprised there was not an overall cardiovascular benefit given the large study size and the nearly 15 mmHg difference in systolic blood pressure”.

The ACCORD results have also been published in the April 29th issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. In an accompanying editorial, Dr Peter M Nilsson (University Hospital, Malmö, Sweden) says that: “The main conclusion to draw from this study must be that a systolic blood pressure target below 120 mmHg in patients with type 2 diabetes is not justified by the evidence”.

INVEST

The INVEST trial randomised 6,400 patients with diabetes and coronary artery disease (CAD) to blood-pressure-lowering therapy based either on a calcium-channel blocker or a beta blocker, plus an ACE inhibitor and/or a thiazide diuretic. The target was a blood pressure of less than 130/85 mmHg.

For the current analysis, patients were categorised according to the degree of blood pressure control actually achieved. Patients with a systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg or higher – almost one-third of patients – were classified as ‘Not Controlled’. Those with a systolic blood pressure below 130 mmHg were classified as ‘Tight Control’ and those with a systolic blood pressure in between were classified as ‘Usual Control’.

During a follow-up period equivalent to more than 16,893 patient-years, researchers found that patients in the ‘Not Controlled’ group had nearly a 50% higher combined risk of death, MI, or stroke when compared with the ‘Usual Care’ group, and those in the ‘Tight Control’ group had a similar risk to those in the ‘Usual Control’ group.

But further analysis showed that lowering systolic blood pressure below 130 mmHg significantly increased the risk of all-cause death when compared to ‘Usual Care’, an increase that became apparent about 30 months into the study and persisted for an additional five years of follow-up. When researchers then analysed blood pressure in 5 mmHg increments in the ‘Tight Control’ group, they discovered that a systolic blood pressure below 115 mmHg was associated with increased mortality.

Lead investigator Dr Rhonda Cooper-DeHoff (University of Florida, Gainesville, USA) said: “Diabetic patients with CAD in whom blood pressure is not controlled have an increased risk for unfavourable cardiovascular outcomes, so the message to lower systolic blood pressure below 140 mmHg is still important. However, it is not necessary to lower systolic blood pressure below 130 mmHg to reduce that risk. Most importantly, reducing systolic blood pressure below 115 mmHg may be associated with increased mortality,” she added.

ACCORD Lipid Trial – no benefit of fibrates in diabetes

Adding a fibrate to a statin in patients with type 2 diabetes did not further improve survival or other key cardiovascular outcomes, in the ACCORD Lipid Trial.

“Overall, the results of the ACCORD Lipid Trial do not support use of combination therapy with fenofibrate and simvastatin to reduce cardiovascular disease in high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes,” said lead investigator Dr Henry Ginsberg (Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, USA).

Patients who began the study with both triglyceride levels in the top third and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels in the bottom third may have benefited from combination therapy, when compared to other study participants.

The trial included 5,518 patients with type 2 diabetes and either pre-existing cardiovascular disease or at least two additional cardiovascular risk factors who were randomly assigned to treatment with simvastatin plus fenofibrate, or to simvastatin plus a placebo.

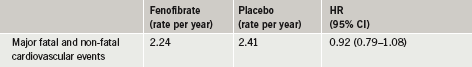

After a five-year follow-up, researchers found that the combination therapy was safe but did not significantly reduce the combined rates of cardiovascular death, non-fatal heart attack or non-fatal stroke, the study’s primary outcome, when compared to simvastatin alone (table 1).

The full ACCORD Lipid results have been published in the April 29th issue of The New England Journal of Medicine.

NAVIGATOR – what role for valsartan and nateglinide in prevention of diabetes and cardiovascular disease?

“Most experts believed that nateglinide would prevent diabetes and that valsartan would reduce cardiovascular events in this population,” said lead investigator, Dr Robert Califf (Duke University, Durham, USA). “Interestingly, with respect to nateglinide, we found the opposite. The results with valsartan confirmed previous studies that showed a reduction in diabetes. It was disappointing that there was no reduction in cardiovascular events but in such a large study, with patients on other therapies that are known to impact cardiovascular disease, this lack of event reduction is consistent with other studies,” he added.

In the study 9,306 patients with glucose intolerance and either cardiovascular risk factors or established cardiovascular disease were randomised to either nateglinide (up to 60 mg three times a day before meals) or placebo, and to either valsartan (up to 160 mg daily) or placebo. All patients were required to participate in a lifestyle programme, with the goal of maintaining a 5% weight loss, increasing physical activity to an average of 30 minutes five days a week, and to follow a low-fat diet.

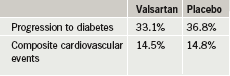

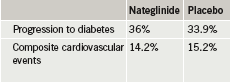

Patients were followed for five years, on average, for development of diabetes and 6.5 years, on average, for cardiovascular disease. Researchers found that valsartan reduced the risk of progression to diabetes by 14%, but did not reduce the cardiovascular end point of death from cardiovascular causes, myocardial infarction, stroke, hospitalisation for heart failure, unstable chest pain, or revascularisation (table 1). Nateglinide failed to reduce both progression to diabetes and cardiovascular risk (table 2).

Investigators speculated that the study’s results may have been influenced by how effective the lifestyle programme was in reducing both diabetes progression and cardiovascular risk. By the end of the study, a large number of patients were also taking medications prescribed by their personal physician to inhibit the renin-angiotensin system or to treat abnormal lipid levels or high blood pressure, and this may have lowered overall risk.

The NAVIGATOR results have now been published in the April 22nd issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

EVEREST – mitral clip as good as heart valve repair surgery

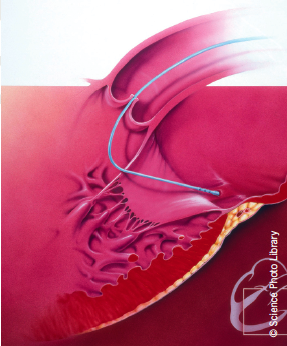

A catheter-mounted device, which acts as a clip to repair leaky heart valves, is a safe and effective alternative to open-chest surgery in selected patients with mitral regurgitation, according to the results of EVEREST II (Endovascular Valve Edge-to-Edge Repair Study). In addition, patients treated with the MitraClip® valve repair system were far less likely to experience a serious complication within 30 days of the procedure.

Lead investigator, Dr Ted Feldman (North Shore University Health System, Evanston, USA) said: “As clinicians, we have seen our patients transformed from highly symptomatic to highly functional with a catheter procedure – and without a long hospital stay or a long recovery period”.

As with other percutaneous procedures, the MitraClip“ device is threaded through the femoral vein in the groin and into the right atrium. A needle puncture in the wall separating the upper chambers of the heart enables the catheter to pass into the left atrium, where the clip is opened up. It is then passed through the mitral valve into the left ventricle. When the heart contracts, the flaps, or leaflets, of the mitral valve fall into the clip, which is then closed, pinning the edges of the leaflets together at their centres. The result is a bow-tie-shaped opening that permits blood flow from the left atrium to the left ventricle during relaxation of the heart, and enables the valve to close more effectively during contraction, rather than allowing leakage of blood backward into the left atrium.

The EVEREST II study was designed to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of the MitraClip“ procedure in comparison with open-chest mitral valve surgery in 279 patients.

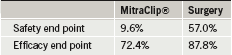

The primary safety end point (a combination of adverse events including death, major stroke, reoperation, urgent/emergent surgery, myocardial infarction, renal failure, and blood transfusions, among others) significantly favoured the MitraClip“ at 30 days (table 1). The need for blood transfusions was the main driver of the safety end point, with a difference of 8.8% vs. 53.2%. The primary efficacy end point, the overall clinical success rate, was numerically higher in the surgery group (see table 1) and the difference met non-inferiority criteria.

Genotyping warfarin patients reduces hospitalisations

Presenting the study, Dr Robert Epstein (Medco Research Institute, New York, USA) explained that when starting warfarin, the dose is normally determined by trial and error, and it can take weeks or even months of repeated blood tests and dose adjustments to determine the right dose for each patient. During that time, patients are at high risk for either thromboembolism from too little warfarin, or bleeding from too much warfarin.

Presenting the study, Dr Robert Epstein (Medco Research Institute, New York, USA) explained that when starting warfarin, the dose is normally determined by trial and error, and it can take weeks or even months of repeated blood tests and dose adjustments to determine the right dose for each patient. During that time, patients are at high risk for either thromboembolism from too little warfarin, or bleeding from too much warfarin.

The MM-WES study enrolled 896 US patients who were beginning warfarin therapy and were members of a prescription benefits plan managed by Medco Health Solutions. Shortly after starting warfarin therapy, patients gave a blood sample or a cheek swab, which was genotyped for two key genotypes – CYP2C9 and VKORC1 – which determine how sensitive each patient is to the drug. The ordering physician received a report of the findings as well as clinical information on how to interpret the findings – i.e. whether to increase or decrease the warfarin dose.

The researchers found that, during the first six months of warfarin therapy, patients who had genetic testing were 31% less likely to be hospitalised for any cause, when compared to an historical control group that did not undergo genetic testing. Patients in the gene-testing group were also 29% less likely to be hospitalised for bleeding or thromboembolism.

The cost of genetic testing – approximately US$ 250 to US$ 400, depending on the laboratory – is justified by the savings, according to Dr Epstein. “If we reduce just two hospitalisations per 100 patients tested, that more than compensates for the cost of genotyping,” he said.

Discussant not impressed

Patients taking warfarin who undergo genotyping to determine their warfarin dose had a 30% reduction in hospitalisations in the MM-WES (Medco-Mayo Warfarin Effectiveness) Study.

But discussant of the study, Dr Mandeep Mehra (University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, USA), criticised the study, saying the historical control group “leaves doubt as to whether the reduction in hospitalisation seen in the genotyping group was actually due to the genotyping results or just that the doctor paid closer attention to these patients”.

Responding to this at a later press conference, Dr Epstein said that the reductions in hospitalisations seen in this study would be more than cost-saving whether it was the genotyping or just the extra attention paid to the patients that brought it about. “If we have a new technology that brings more precision to dosing, then that’s got to be good,” he added.

Concerns over drug-eluting stents in STEMI?

Drug-eluting stents may be associated with an increase in the risk of long-term stent thrombosis and cardiac death compared with bare-metal stents in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), according to the results of two new studies.

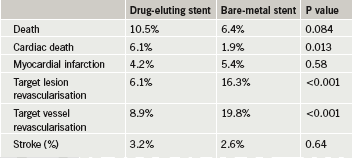

In the DEDICATION trial, the drug-eluting stent group showed an increased risk of cardiac death at three years compared to the patients who received a bare-metal stent.

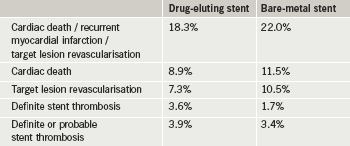

And in the PASSION trial, there was no difference between the two types of stents in the composite end point of cardiac death, recurrent myocardial infarction, or target lesion revascularisation at five years, but there was a trend towards very late stent thrombosis in the drug eluting-stent group.

The DEDICATION trial involved 626 STEMI patients who received either a bare-metal stent or a drug-eluting stent. Results at eight months, reported previously, showed a trend towards an increased risk of cardiac mortality (mainly from heart failure) with the drug-eluting stent group, and this was still present at the three-year point (table 1), lead investigator Dr Peter Clemmensen (Copenhagen University Hospital, Denmark) reported. Revascularisation rates, however, were significantly lower in the drug-eluting stent arm.

Dr Clemmensen stressed that this study was too small to draw any definite conclusions and the increase in cardiac death might have been due to the play of chance. “We’ve seen a signal here, but before doctors stop using these devices, I would urge them to wait for the results of larger studies,” he said.

PASSION

The PASSION study enrolled 619 patients with STEMI who received either a drug-eluting stent or a bare-metal stent. All patients were given clopidogrel for at least six months and aspirin long-term.

At five years, results (table 2) showed there was no statistical difference in the rate of the composite end point (cardiac death, recurrent myocardial infarction or target lesion revascularisation). Definite stent thrombosis was, however, twice as high in the drug-eluting stent group versus the bare-metal stent group, although this was not statistically significant.

CABANA: catheter ablation looks good in AF

Catheter ablation appears to be more effective than drug therapy in treating atrial fibrillation (AF), according to the the CABANA (Catheter Ablation Versus Anti-arrhythmic Drug Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation) pilot study.

This study is one of the first to evaluate the feasibility of catheter ablation in patients with more advanced AF and substantial underlying cardiovascular disease, lead investigator Dr Douglas Packer (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, USA) explained.

This study is one of the first to evaluate the feasibility of catheter ablation in patients with more advanced AF and substantial underlying cardiovascular disease, lead investigator Dr Douglas Packer (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, USA) explained.

“These results establish the feasibility and importance of conducting an extended pivotal trial critical for establishing long-term outcomes, mortality, quality of life, and cost of ablation and drug therapy for atrial fibrillation,” he said.

For the study, 60 patients with AF and multiple other cardiovascular issues (hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease or heart failure) were randomised to drug therapy or catheter ablation. Results showed that catheter ablation was more effective than drug therapy for preventing recurrent symptomatic AF. Treatment success rates in these patients (some of whom had persistent and long-standing persistent AF), however, were lower than observed in other randomised clinical trials. Late recurrent atrial fibrillation may also diminish the overall effectiveness of ablation therapy, Dr Packer said.

The CABANA pivotal trial will further examine these issues, and is currently recruiting patients.

JETSTENT – rheolytic thrombectomy before stenting in STEMI

Conducting rheolytic thrombectomy (removal of the thrombus) before direct infarct-related artery stenting in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) produced better clinical results than performing direct stenting alone, in the JETSTENT trial.

The study included 501 patients and found that significantly more patients receiving rheolytic thrombectomy in addition to direct stenting experienced resolution of their ST-segment elevation in the designated time frame than those patients receiving stenting alone (85.8% vs. 78.8%). There was also a strong trend towards a reduction in infarct size as assessed by one-month scintigraphy in the thrombectomy group (6% vs. 12.6%). The researchers also found a significant decrease in major cardiovascular events for patients randomised to receive rheolytic thrombectomy than patients in the direct stenting alone arm both at one month (3.1% vs. 6.9%) and at six months (11.9% vs. 20.6%).

Noting that these results contrast with those of a previous study (AiMI) which found that, rheolytic thrombectomy did not lead to better reperfusion and was associated with a significantly higher mortality rate at 30 days and six months post-procedure, JETSTENT investigator, Dr David Antoniucci (Careggi Hospital, Florence, Italy) pointed out that the two studies differed in several ways. The JETSTENT study included only patients with angiographically visible thrombus; it used a different technique for thrombus removal; and it has a narrower definition of ST-segment elevation resolution.

Discussing the trial, Dr William O’Neill (University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, USA), said the results highlighted the importance of thrombus burden in STEMI patients. But other panel members believed there was not enough evidence to support the routine use of thrombectomy prior to stenting.

CILON-T: adding cilostazol to clopidogrel and aspirin after stenting

There was no significant benefit in reducing clinical events of adding a third antiplatelet drug – cilostazol – to aspirin and clopidogrel after drug-eluting-stent placement in the CILON-T study. But triple therapy did improve post-treatment platelet reactivity, and the trial was underpowered for hard clinical events.

In the trial, 960 coronary disease patients were given either standard therapy of aspirin and clopidogrel or a triple antiplatelet regimen of aspirin, clopidogrel, and cilostazol for six months after drug-eluting-stent placement.

Results showed that post-treatment platelet reactivity, as measured by P2Y12-receptor reaction units (PRU), decreased from 255.7 in the clopidogrel/aspirin group to 210.7 in the triple therapy arm. But the primary clinical end point (cardiac death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, ischaemic stroke, and target lesion revascularisation) was not significantly different between the two groups (8.5% with triple therapy versus 9.2% with dual therapy; p=0.73).

Lead investigator Dr Hyo-Soo Kim (Seoul National University Hospital, Korea) showed data demonstrating that platelet reactivity was directly correlated with clinical outcome and that patients in the lowest tertile of platelet reactivity (i.e. PRU values of 0 to 184 units) had zero clinical events.

“Based on these results, we believe that PRU measurements may be useful in predicting risks after drug-eluting-stent implantation and that if PRU readings are high, a third antiplatelet drug should be considered,” Dr Kim concluded.

Discussing the study, Dr Robert Harrington (Duke University, Durham, USA) suggested that the trial was underpowered to see differences in clinical outcomes. He also pointed out that cilostazol has gastrointestinal and heart rate side effects, which may not make it the best agent to add in.

Women with MI are under-treated

Women might be more likely to survive a myocardial infarction (MI) if they were treated more like men, with increased use of angioplasty and other invasive techniques, a French study suggests.

The study involved more than 3,000 patients admitted to hospital for an MI. Results showed that women were far less likely than men to go to the cath lab for angiography or angioplasty, and about twice as likely to die within a month. But when the patients were matched by both baseline clinical characteristics and treatments, death rates were similar among men and women.

Presenting the study, Dr Francois Schiele (University Hospital of Besancon, France) said: “When there are no clear contraindications, women should be treated with all recommended strategies, including invasive strategies”.

She explained that several previous studies have suggested that women have a higher risk of death after MI than men, but the reasons have been unclear. Her group analysed data from a regional registry that included all patients treated for an MI in 2006 and 2007. Of the 3,510 patients in the study, 32% were women, and they were, on average, nine years older than men, had more health problems, received fewer effective treatments for MI, and were nearly twice as likely to die, both during the initial hospital stay and over the following month.

After propensity scoring to match patients by baseline characteristics, it was found that despite very similar clinical characteristics, men were 57% more likely than women to undergo coronary angiography. Among ST-elevation MI patients, men were far more likely than women to receive some reperfusion treatment. Thrombolysis was used 72% more often in men and angioplasty was used 24% more often in men.