Incidence of stroke attributable to atrial fibrillation increases from 1.5% at age 50–59 years to 23.5% at age 80–89 years. The use of oral anticoagulants to reduce the risk of stroke is well established, but all the available agents can cause bleeds if used in excess dose, in high-risk patients or in patients with reduced kidney function.

This article highlights the need to assess kidney function as stated in the newly published European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) practical guide on the use of the new oral anticoagulants (NOACs).1 The EHRA guide has a section on NOACs for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) where it is stated that “a careful follow-up of renal function is required in CKD patients, since all (NOACs) are cleared more or less by the kidney”. It continues “in the context of NOAC treatment, creatinine clearance is best assessed by the Cockcroft method, as this was used in most NOAC trials”.

The authors discuss the issues and present a simple guide on why and how to use the Cockcroft Gault equation for kidney function estimation. They also note that for drug and dosing decisions, reduced kidney function, for whatever reason (not just where a patient has been assessed as having CKD), needs to be assessed to reduce the risk of harm.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is an epidemic of our time, with prevalence increasing from 0.5% at age 50–59 years to almost 9% at age 80–89 years.2 AF predisposes to stroke and thromboembolism with an approximately five-fold greater risk than that of people without AF; the incidence of strokes attributable to AF increases from 1.5% at age 50–59 years to 23.5% at age 80–89 years.2

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is an epidemic of our time, with prevalence increasing from 0.5% at age 50–59 years to almost 9% at age 80–89 years.2 AF predisposes to stroke and thromboembolism with an approximately five-fold greater risk than that of people without AF; the incidence of strokes attributable to AF increases from 1.5% at age 50–59 years to 23.5% at age 80–89 years.2

The use of anticoagulants to reduce the risk of stroke in AF is well established.2 Three new ‘novel oral anticoagulants’ (NOACs) are now licensed for stroke reduction in AF as alternatives to the coumarins (e.g. warfarin) and have been approved by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE):3-5 dabigatran,6 a direct thrombin (IIa) inhibitor, rivaroxaban7 and apixaban,8 both Xa inhibitors. These agents have a more stable dose response than warfarin but are dependent on renal clearance; dose modification is recommended in patients with reduced kidney function. The population most in need of anticoagulation to reduce the risk of AF-related stroke is generally older with multiple manifestations of cardiovascular disease, so chronic kidney disease (CKD) is likely.

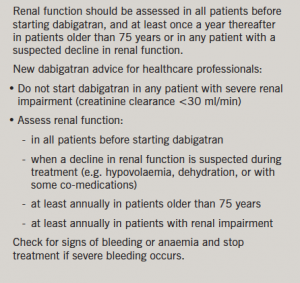

Used correctly, NOACs are at least as safe as well-controlled warfarin. Like warfarin they can cause bleeds, especially if used in excess doses, in patients with higher risks for bleeds, and in reduced kidney function. A number of cases of serious and fatal haemorrhage have been reported in Japanese elderly patients with reduced kidney function who were receiving dabigatran.9 This resulted in the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) issuing a reminder about appropriate use in patients with reduced kidney function (box 1).9 All patients were reported to be older than 75 years, with CKD and additional risk factors for bleeding. While all received the lower dose of dabigatran (i.e. 220 mg/day) half had creatinine clearance <30 ml/min, which is a contraindication for dabigatran therapy.9

Rivaroxaban and apixaban are also likely to increase the risk of bleeding if used in renal impairment, and there are clear recommendations for use in the manufacturer Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPCs).10-13 However, the SmPC is not easy for prescribers to access at time of prescribing and, although they are summarised in the British National Formulary (BNF),14 the recommendations are difficult to interpret.

Renal function estimation for drug dosing

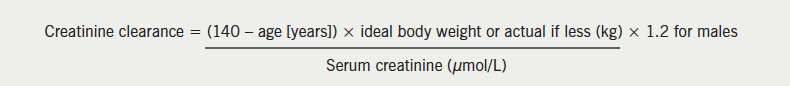

An estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation is now nationally reported when serum creatinine is monitored, following the introduction of CKD guidelines.15,16 eGFR allows staging of renal function to guide monitoring and treatment of CKD, but it was not designed for drug dosing decisions. Historically, the Cockcroft & Gault equation17 (CG) has been used for estimating kidney function for drug use and dosing decisions (box 2).

The BNF14 now quotes renal function recommendations as ‘eGFR’, but the figures are those from the SmPCs, which are estimated creatinine clearance (eCrCl). They state that for most patients eGFR is an adequate estimate, but that calculation with the Cockcroft & Gault equation (eCrCl-CG) should be used for low therapeutic index and high-risk drugs. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guideline18 states that alterations in drug dosing should be made on the basis of eCrCl-CG, as virtually all published recommendations for dose adjustment in patients with reduced kidney function, including the BNF and SmPCs are based on creatinine clearance estimated using CG.

The results of several retrospective studies suggest that use of the MDRD equation for drug dosing often yields higher doses than does the CG equation; the most conservative kidney function estimate should be used with narrow therapeutic window drugs and in high-risk subgroups, such as the elderly.19-21 In a large (n=46,942), retrospective study comparing use of the CG and MDRD equations, major bleeding events were more frequent in individuals who received an excess dose of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors as assessed by the MDRD equation versus CG: 21.8% vs. 17.8%; odds ratios MDRD 1.57 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.35–1.84), CG 1.31 (95%CI 1.12–1.54).22 A study using gentamicin blood levels found that MDRD overestimated renal function as age increased (29% and up to 69%) and CG underestimated renal function, though this was of a smaller magnitude (10%). CG was consistent across age and so better suited for dose calculation, especially in the elderly; age significantly influenced MDRD overestimation (p=0.037).23

Serum creatinine is derived from muscle turnover, and so, the weight element of the equation should be an indication of muscle mass, not excess fat; Cockcroft and Gault originally recommended using ideal or lean body weight in patients with pronounced obesity or volume overload,17 and the BNF also states that the weight component of the equation should be ideal body weight.14 This is particularly important when assessing kidney function for dosing decisions in overweight patients.

Decision support for oral anticoagulant dosing in reduced kidney function

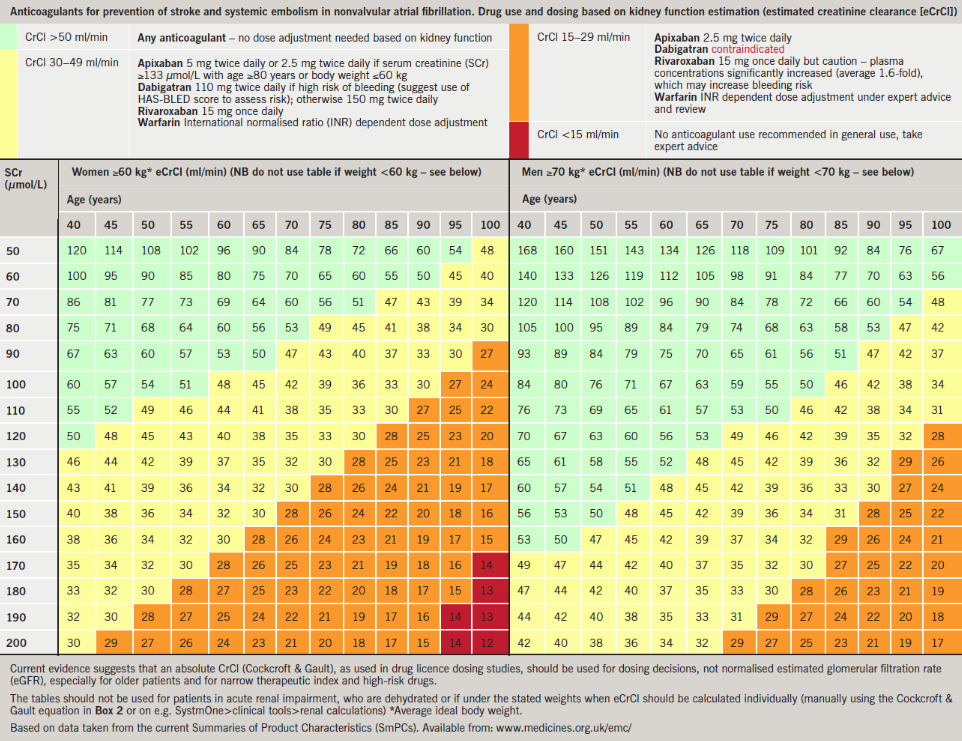

The ‘dosing in reduced kidney function chart’ (figure 1) was developed to provide a visual aid on the effect of kidney function, as well as a resource to give an indication of drug choice and dosing decisions based on eCrCl.

It uses an average ideal bodyweight of 60 kg for females and 70 kg for males to give an indication of eCrCl. It should not be used for patients in acute kidney injury, who are dehydrated, or if they are under the stated weights; eCrCl-CG should then be calculated individually (manually or on electronically available calculators or decision-support systems, such as SystmOne>clinical tools>renal calculations). Patients with high muscle mass would need actual weight to be used.

To assess the individual risk of major bleeding in patients with AF, the HAS-BLED score has been suggested.24

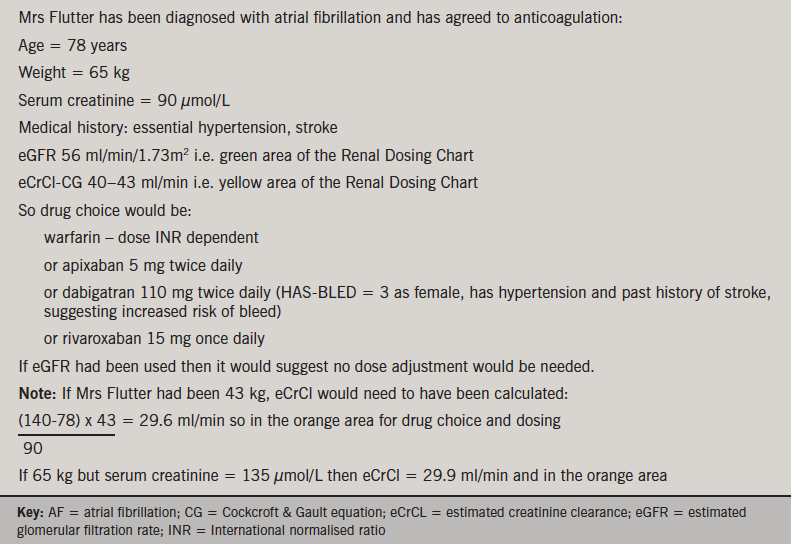

Box 3 provides a worked case example showing that using eGFR would not have suggested a dose change if an NOAC was to be prescribed, and the patient could have been at a higher risk of harm.

The ‘dosing in reduced kidney function chart’ shown in figure 1 has been included in primary care guidelines in Bradford, Bury, Manchester and Buckinghamshire with positive initial feedback. It has been included as part of local guidelines for use of NOACs and in AF guidelines issued to GPs; it is also being used as a quick reference guide for use in anticoagulant clinics instead of having to calculate CrCl every time when considering NOACs as alternatives to warfarin. User testing, application to other drugs, and use for education, are underway, and development of more targeted computer-decision support is planned.

Information is accurate at time of publication; manufacturer recommendations may change so there may be a need to check the SmPC.

Summary

Clearance from the body of the new oral anticoagulants is dependent on kidney function and, to reduce risk of bleeds, the level of renal function should be assessed using estimated creatinine clearance. A ‘dosing in reduced kidney function chart’ has been developed to aid prescribers in drug choice and dosing decisions.

Conflict of interest

SW has received an honorarium from Bayer; DP has received an honorarium for advice provided to Boehringer Ingelheim; MF has received honoraria and travel assistance from Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, INRStar, Medtronic, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis; AL has received honoraria from AM Pharma, Abbott and Baxter, and an educational grant from B Braun.

Key messages

- The clearance of the new oral anticoagulants from the body is dependent on kidney function

- To reduce risk of bleeding, the level of kidney function should be assessed using estimated creatinine clearance

- A ‘dosing in reduced kidney function chart’ has been developed to aid prescribers in drug choice and dosing decisions

References

- Heidbuchel H, Verhamme P, Alings M et al. EHRA Practical Guide on the use of new oral anticoagulants in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: executive summary. Eur Heart J 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht134

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. The managment of atrial fibrillation. Clinical Guideline 36. London: NICE, 2006. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG36

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. TA249. Dabigatran etexilate for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in atrial fibrillation. London: NICE, 2012. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/TA249

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. TA256. Atrial fibrillation (stroke prevention) – rivaroxaban. London: NICE, 2012. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/TA256

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Stroke and systemic embolism (prevention, non-valvular atrial fibrillation) – apixaban. ID500 in progress. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/TA/Wave27/9

- Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1139–51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0905561

- Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;365:883–91. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1009638

- Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJV et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;365:981–92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1107039

- Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Dabigatran (Pradaxa): risk of serious haemorrhage – need for renal function testing. Drug Safety Update 2011;5(5). http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Safetyinformation/DrugSafetyUpdate/CON137771

- eMedicines Compendium UK. Summary of Product Characteristics – warfarin. http://www.medicines.org.uk/EMC/medicine/25626/SPC/Warfarin+0.5mg+Tablets/ [accessed 18/04/2013].

- eMedicines Compendium UK. Summary of Product Characteristics – dabigatran. http://www.medicines.org.uk/EMC/medicine/24839/SPC/Pradaxa+150+mg+hard+capsules/ [accessed 18/04/2013].

- eMedicines Compendium UK. Summary of Product Characteristics – rivaroxaban. http://www.medicines.org.uk/EMC/medicine/25586/SPC/Xarelto+20mg+film-coated+tablets/ [accessed 18/04/2013].

- eMedicines Compendium UK. Summary of Product Characteristics – apixaban. http://www.medicines.org.uk/EMC/medicine/27220/SPC/Eliquis+5+mg+film-coated+tablets/ [accessed 18/04/2013].

- BMJ Group and Royal Pharmaceutical Society. British national formulary. Volume 64. London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press, September 2012.

- The National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Chronic kidney disease. National clinical guideline for early identification and management in adults in primary and secondary care. NICE clinical guideline 73. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2008. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/12069/42116/42116.pdf

- Joint Specialty Committee for Renal disease of the Royal College of Physicians of London and the Renal Association. Chronic kidney disease in adults: UK guidelines for identification, management and referral. London: Royal College of Physicians of London, 2005. http://www.renal.org/CKDguide/full/UKCKDfull.pdf

- Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 1976;16:31–41.

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN guideline 103. Diagnosis and management of chronic kidney disease – a national clinical guideline. Edinburgh: SIGN, 2008. http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign103.pdf

- Nyman HA, Dowling TC, Hudson JQ et al. Comparative evaluation of the Cockcroft-Gault equation and the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equation for drug dosing. An opinion of the Nephrology Practice and Research Network of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy 2011;31:1130–44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1592/phco.31.11.1130

- Helou R. Should we continue to use the Cockcroft-Gault formula? Nephron Clin Pract 2010;116:c172–c186. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000317197

- Spruill W, Wade W, Cobb H. Comparison of estimated glomerular filtration rate with estimated creatinine clearance in the dosing of drugs requiring adjustments in elderly patients with declining renal function. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2008;6:153–60.

- Melloni C, Peterson ED, Chen AY et al. Cockcroft-Gault versus modification of diet in renal disease: importance of glomerular filtration rate formula for classification of chronic kidney disease in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:991–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2007.11.045

- Roberts GW, Ibsen PM, Schioler CT. Modified diet in renal disease method overestimates renal function in selected elderly patients. Age Ageing 2009;38:698–703.

- Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R et al. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleed in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest 2010;138:1093–1100. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.10-0134