We present an investigation into the safety of providing training in coronary angiography within a district general hospital setting.

Introduction

In the modern era, patient safety has become one of the most important issues facing doctors and institutions. Cardiology is a craft speciality. Procedures must be learnt by trainees, but there is a risk, in so doing, of harming patients.

The purpose of this study was to ask whether it is possible, albeit within a single institution, to provide training in coronary angiography at a district general hospital (DGH) without causing harm, by comparing the complication rate of trainees with consultants in a large case series.

Methods

Between August 2010 and December 2013, procedural complications resulting from cardiac catheterisation at Chesterfield Royal Hospital were recorded in a prospective registry. Major complications were defined as stroke, perforation of a cardiac chamber, coronary dissection, coronary occlusion or pseudoaneurysm of a peripheral vessel requiring intervention, or any complication requiring admission. All other complications were minor.

For statistical analysis, cases were divided into trainee-led and consultant-led groups.Comparisons were made using Chi-squared and student t-tests as appropriate.

Results

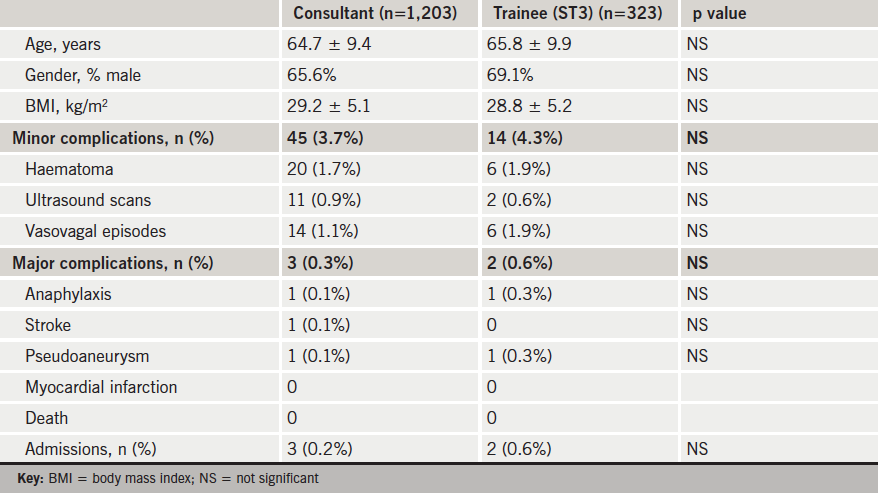

A total of 1,526 diagnostic angiograms were performed: 1,203 (78.8%) consultant-led and 323 (21.2%) trainee-led. Access was via the femoral artery in 1,490 (97.7%) cases and the radial artery in 36 (2.3%) cases. Patient demographics in both groups were comparable (table 1). Five patients were admitted following catheterisation: two suffered anaphylactic contrast reactions and one a stroke. There were no deaths. There were 26 vascular access complications observed: 13 patients were referred for ultrasound examination and two pseudoaneurysms required injection. There were no significant differences in complication rates between consultant-led and trainee-led cases.

Discussion

There is evidence that outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and angiography without PCI, are better with more experienced operators and, therefore, by implication, inexperience can result in patient harm.1-4 However, results from two recent single-centre studies suggest that close senior supervision of less experienced operators may reduce the increased patient risk associated with inexperience.5,6

The last decade has seen training in coronary angiography move from the regional centres to the DGH. The safety implications of this shift have not been examined. In this prospective audit, we set out to examine the effect on patient risk of training inexperienced operators in diagnostic angiography in a DGH. Over the period reported, six trainees each performed their first 50 cases of coronary angiography under direct consultant supervision. Complication rates reported here compare well with previously published registries.6,7 We did not monitor renal function or collect data on the volume of contrast used. However, these data show that diagnostic cardiac catheterisation is a safe procedure and that the training of inexperience operators does not expose patients to increased clinical risk.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

1. Hannan EL, Wu C, Walford G et al. Volume-outcome relationships for percutaneous coronary interventions in the stent era. Circulation 2005;112:1171–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.528455

2. McGrath PD, Wenn DE, Dickens JD Jr et al. Relation between operator and hospital volume and outcomes following percutaneous coronary interventions in the era of the coronary stent. JAMA 2000;284:3139–44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.24.3139

3. Srinivas VS, Hailpern SM, Koss E et al. Effect of physician volume on the relationship between hospital volume and mortality during primary angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:574–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.056

4. Ammann P, Brunner-Le Rocca HP, Angehrn W et al. Procedural complications following diagnostic coronary angiography are related to the operator’s experience and the catheter size. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2003;59:13–18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ccd.10489

5. Stolker JM, Allen DS, Cohen DJ et al. Comparison of procedural complications with versus without interventional cardiology fellows-in-training during contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 2014;113:44–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.08.037

6. Applegate RJ, Sacrinty MT, Kutcher MA et al. Trends in vascular complications after diagnostic cardiac catheterization and percutaneous coronary intervention via the femoral artery. JACC Cardiovascular Interv 2008;1:317–26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2008.03.013

7. West R, Ellis G, Brooks N. Complications of diagnostic cardiac catheterisation: results from a confidential inquiry into cardiac catheter complications Heart 2006;92:810–14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2005.073890