A 46-year-old man with cutaneous sarcoidosis and pulmonary involvement was referred to a cardiologist for possible pulmonary hypertension in view of increasing shortness of breath. Echocardiogram findings and electrocardiogram (ECG) changes prompted the need for coronary angiography, which was subsequently normal.

Cardiac sarcoidosis was one of the differential diagnoses. The patient was booked for a treadmill test. Unfortunately, in the interim, the patient had an episode of collapse while playing football. The local district hospital discharged the patient after finding normal computed tomography (CT) brain scan and negative troponin. He was re-admitted with a pre-syncopal episode and ambulatory ECG monitoring revealed non-sustained ventricular tachycardia. A cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan was arranged followed by insertion of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD).

This case report and literature review highlights the importance of cardiac screening in patients deemed ‘high risk’ for sudden cardiac death, and the need for immediate investigation and treatment. Current guidelines are yet to be universally accepted, so such cases are important in highlighting current methods of investigation and treatment.

Introduction

Cardiac sarcoidosis can present in a broad spectrum of entities ranging from a benign condition, which is diagnosed incidentally, to a potentially serious disease leading to sudden cardiac death, which only becomes apparent at autopsy, as is the case in 5% of the affected population.1 Due to its subtle, but also sometimes fatal presentation, cardiac sarcoid is hugely underdiagnosed, and awareness of such cases should be brought to light whenever possible.

This case report highlights the importance of being aware of the potential presentations of cardiac involvement in patients with sarcoidosis and the general investigations and management that are common place in current practice.

Case report

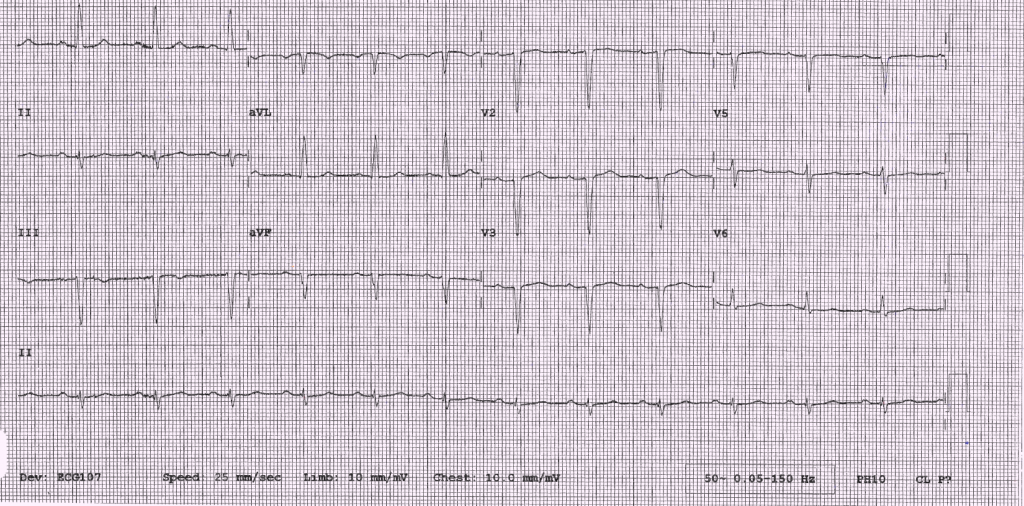

A 46-year-old man, with a previous biopsy-proven diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis with pulmonary involvement, was referred two years after his first diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis to a cardiologist to investigate further for possible pulmonary hypertension in view of increasing shortness of breath. He had an echocardiogram, which showed severely impaired left ventricular function with a hypokinetic anterior septum. Together with the electrocardiogram (ECG) findings (figure 1) both coronary artery disease and cardiac sarcoid were within the list of differential diagnoses. Therefore, a coronary angiogram was undertaken, which was deemed normal. In the interim period, the patient had an episode of syncope while playing football. His local hospital was unaware of the background and current investigations, and so, after a normal computed tomography (CT) brain scan and observation period, the patient was discharged.

A cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was booked on the patient’s subsequent appointment to his cardiologist, and an exercise-tolerance test was arranged to see if he had any evidence of inducible ventricular arrhythmias. This showed a left bundle branch block (LBBB) at peak of stress and the patient remained asymptomatic throughout.

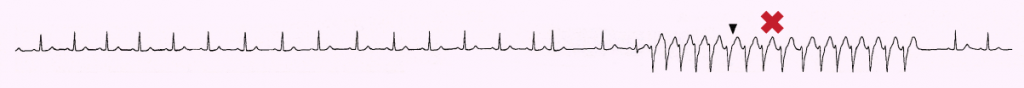

The patient was re-admitted with pre-syncope six months later. Ambulatory ECG recordings (figure 2) showed non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT) prompting urgent MRI (figure 3) and subsequent implantable cardioverter debfibrillator (ICD) insertion.

The patient was commenced on prednisolone. At 12 months follow-up, a gallium scan with single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) was arranged to determine disease activity. This showed active inflammation in the parotid glands and also in the left ventricular apex. This led to the initiation of methotrexate, with subsequent scans showing a decline in disease activity.

Discussion

Cardiac sarcoid is largely underdiagnosed in the population. At present, there is no clear consensus on the detection, monitoring and treatment process, meaning the physician must manage each case on a more individual basis.

The symptoms and signs of cardiac sarcoid are dependent upon the extent and location of the granulomatous formation. Within the heart, it may involve pericardium, myocardium and endocardium. Aetiology is unclear: genetic, environmental and immune phenomena may contribute.

The most common conduction abnormality in cardiac sarcoidosis is third-degree atrioventricular (AV) block or complete heart block. This is followed by ventricular tachycardia. Among bundle branch blocks, right is more frequent than the left. Heart failure is the most common cause of death in sarcoidosis, and studies show this to be secondary to papillary infiltration in most of the cases.

The diagnosis of cardiac sarcoid can be challenging, and a high index of suspicion should be kept. The patients in whom sarcoidosis should be suspected include those with: sustained ventricular tachycardia, young patients ( <55 years) with unexplained heart block and extra cardiac sarcoidosis.

The 1999 Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society, the European Respiratory Society and the World Association for Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders considers cardiac dysfunction, ECG abnormalities, and thallium-201 imaging defects, with or without endomyocardial biopsy, as evidence of cardiac sarcoidosis.

Several radionuclide techniques are available to image inflammation. 18F-flurodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) scan shows more sensitivity than thallium-201 and gallium-67 scans in detecting cardiac sarcoidosis active tissue and a scar, but with less specificity.2,3 It can also be used to follow treatment response.4

The mainstay of treatment for cardiac sarcoid is that of corticosteroids, in order to halt or regress the inflammation and fibrosis associated with this pathology. However, it is impossible to predict which patients will respond to such therapy, and, thus, the implantation of a primary preventative ICD is largely recommended in both national and international guidelines with regards to device therapy in such cases. The role of secondary agents, such as methotrexate, in cases where glucocorticoids are unsuccessful, has a limited evidence base, but has been shown in patient cohort studies to have a role.

Evidence to date suggests cardiac involvement in sarcoidosis carries a higher morbidity and mortality than in those patients exempt of cardiac involvement.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

1. Johns CJ, Michele TM. The clinical management of sarcoidosis. A 50-year experience at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Medicine (Baltimore) 1999;78:65–111. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005792-199903000-00001

2. Okayama K, Kurata C, Tawarahara K, Wakabayashi Y, Chida K, Sato A. Diagnostic and prognostic value of myocardial scintigraphy with thallium-201 and gallium-67 in cardiac sarcoidosis. Chest 1995;107:330–4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.107.2.330

3. Abdul RD, Byron RW. Cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart 2006;92:282–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2005.080481

4. Youssef G, Beanlands RSB,

Birnie DH, Nery PB. Systemic disorders in heart disease. Cardiac sarcoidosis: applications of imaging in diagnosis and directing treatment. Heart 2011;97:2078–87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2011.226076