Pulmonary hypertension moves into new era

The launch of new pulmonary hypertension (PH) guidelines was covered in several sessions at the recent European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Congress, held recently in London.

Speaking at one of these sessions – an Actelion-sponsored symposium – Dr Gerry Coghlan (Royal Free Hospital, London) described the huge amount of progress in PH in the last 20 years. Whereas in 1995 only one therapy was available, we now have 10 therapies in the UK and there are more elsewhere. “We now have clear evidence that different types of combination therapies improve the outcome in patients with PH,” he said.

Progress in this field has included:

Progress in this field has included:

- The elucidation of new targets for future PH therapies from basic science and genetics research

- Improvements in patient care delivery structures which have enabled patients to receive more rapid up-front therapy

- Better understanding of screening techniques, which has enabled patients to be diagnosed earlier to try and prevent progression to end-stage disease

- Better disease registries, which are helping to understand the trajectory of the disease and also its prognostic indicators

- We also have “very vocal and powerful patient organisations that are providing much support for patients,” said Dr Coghlan.

The consequences of all this, Dr Coghlan said, is that PH is gradually becoming a “chronic disease which patients have to live with” rather than a “lethal disease”.

The guideline

In a special session on the new guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of PH, jointly authored by a Task Force of the ESC and the European Respiratory Society (ERS), Dr Simon Gibbs (Imperial NHS Trust, London) described the definition, classification, diagnosis and screening of PH.

PH is a pathophysiological disorder, which may involve multiple clinical conditions and complicate the majority of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. It is defined haemodynamically as a mean pulmonary arterial pressure ≥25 mmHg at rest, as assessed by right heart catheterisation.

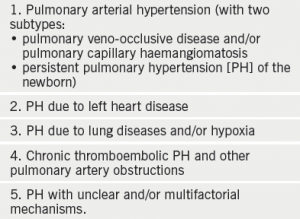

The new clinical classification of PH includes five major types (see table 1).

Adult and paediatric patients have an updated common clinical classification in the new guidelines, along with an updated diagnostic algorithm and novel screening strategies.

The importance of expert referral centres in the management of PH patients has been highlighted in both the diagnostic and treatment algorithms and it is emphasised that echocardiography is not sufficient to support a treatment decision about drug therapies. Cardiac catheterisation is required and notably, it is recommended that right heart catheterisation should be performed in expert centres.

New developments on pulmonary arterial hypertension severity evaluation and on treatments and treatment goals are reported, including combination therapy and two new drugs recently approved. The treatment algorithm has been updated accordingly.

Treatments for pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) recommended in the new guidelines were presented by Dr Marius Hoeper (Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany). Recommended approaches were:

- General measures, e.g. physical activity, genetic counselling etc.

- Supportive therapy, e.g. oral anticoagulants, anaemia and iron status

- Specific drug therapy with calcium channel blockers (nifedipine, diltiazem and amlodipine), endothelin receptor antagonists (ambrisentan, bosentan, macitentan), phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitors and guanylate cyclase stimulators (sildenafil, tadalafil, vardenafil, riociguat), prostacyclin analogues and prostacyclin receptors agonists (beraprost, epoprostenol, iloprost, treprostinil, selexipag) and experimental compounds and strategies

- Combination therapy

- Drug interactions

- Balloon atrial septostomy

- Advanced right ventricular failure

- Transplantation.

A treatment algorithm is also included and the diagnosis and treatment of PAH complications are presented. Finally, end-of-life care and ethical issues are discussed. This same approach is followed for specific PH subsets (paediatric, left heart disease or lung diseases/hypoxia, from chronic thromboembolic PH, etc).

At the end there is a definition of a PH referral centre and a complete online addenda with extra tables, figures and text with the pathology and pathobiology of PH, a proposal for a screening programme and a set of quality of life measurements

The guidelines can be accessed at: http://www.escardio.org/Guidelines-&-Education/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Pulmonary-Hypertension-Guidelines-on-Diagnosis-and-Treatment-of/

They have also been published in the European Heart Journal (doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu317) and the European Respiratory Journal (doi: 10.1183/13993003.01032-2015).

The 10 PH commandments

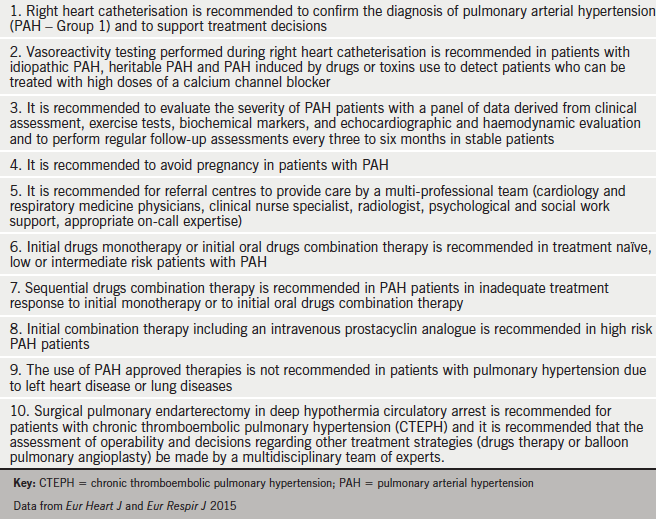

Summarising much of the guidelines and recommendations on PH, Professor Nazzareno Galiè (University of Bologna, Italy) recommended 10 Commandments should be followed (see table 2).

Sleep disordered breathing in PAH

There were many other abstracts on PH presented during the Congress. One looked at the prevalence of sleep disordered breathing (SDB) and its clinical implications in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) patients which remains unclear (Wiklo K, et al. Eur Heart J 2015;36 [abstract supplement] 456–7).

Dr K Wiklo (Medical University of Lodz, Poland) have compared the prevalence of SDB in patients with PAH of different aetiologies. They studied 81 patients who were optimally treated for heart failure, using Holter monitors, measuring NT-proBNP (natriuretic peptide) and estimating the aponea-hypopnea (eAHI) index.

The study was divided in to two groups, 39 patients had coronary artery disease with reduced left ventricular (LV) ejection fractions, and 42 PAH patients (19 idiopathic, 17 congenital heart defects and six connective tissue diseases).

Findings showed that SDB was less common in patients with PAH than in heart failure-induced PAH, but it still affected one third of patients. Generally eAHI was higher in left ventricular dysfunction than in PAH, and in those with left ventricular heart failure, higher eAHI indicated more severe haemodynamic dysfunction, whereas in PAH it was associated with clinical presentation at a younger age.

SDB affects up to 70% of heart failure patients with LV dysfunction and it is associated with poorer outcomes. The high overall prevalence of SDB suggest that further studies are necessary to determine the clinical impact of this phenomenon, especially in PAH patients, the authors conclude.