Definition of ACS

Acute coronary syndromes (ACS) include unstable angina and acute myocardial infarction (AMI). AMI is classified according to those patients with electrocardiographic ST-segment elevation, ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and those without electrocardiographic ST-segment elevation, non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI).1 The requirement for a diagnosis of AMI in the universal definition is the detection of troponin release from injured cardiac myocytes with at least one value >99th centile of the upper reference limit.1 Diagnosis is confirmed only if this is associated with at least one of: symptoms of ischaemia, new ST-segment or T-wave changes or new left bundle branch block on electrocardiography (ECG), development of pathological Q-waves on ECG, imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional wall motion abnormality or the identification of an intracoronary thrombus by angiography or at postmortem examination.

Rates of AMI in the UK

In 2014/15, there were 83,842 admissions to National Health Service (NHS) hospitals in England and Wales, Northern Ireland and Isle of Man with AMI as recorded in the UK national registry,2 Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project (MINAP). Of these, STEMI and NSTEMI comprised 40.5% and 59.5%, respectively. The ratio of STEMI to NSTEMI hospitalisations as recorded in MINAP has not changed over the last five years, from 1:1.50 in 2009/10 to 1:1.47 in 2014/15 (figure 1).2,3 Data from the British Heart Foundation (BHF) report that about 530 people are hospitalised each day in the UK with AMI.4 Primary care data from 2013 in the UK, suggests that the prevalence of AMI in men is about three-fold greater than for women, and that over 915,000 people in the UK have had an AMI.5

While recent data from MINAP suggest rates of hospitalised AMI have remained constant at about 80,000 cases annually, evidence from temporal analyses of national data extending earlier in time suggests that the incidence of ACS is in decline. A UK study using Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) reported a decrease, between 2002 and 2010, in the age standardised AMI event rate per 100,000 population in men of 33% from 230 (95% confidence interval [CI] 228 to 232) to 154 (95% CI 153 to 155) and in women of 31% from 95.4 (95% CI 94.5 to 96.3) to 66.0 (95% CI 65.3 to 66.7).6 Community-based data from the USA also report a decline in the incidence of AMI between 1998 and 2008, which was driven by a decrease in the incidence of STEMI.7 Notably, the rate of NSTEMI increased, and suggests a changing pattern of presentation with ACS.

Survival and re-event rates

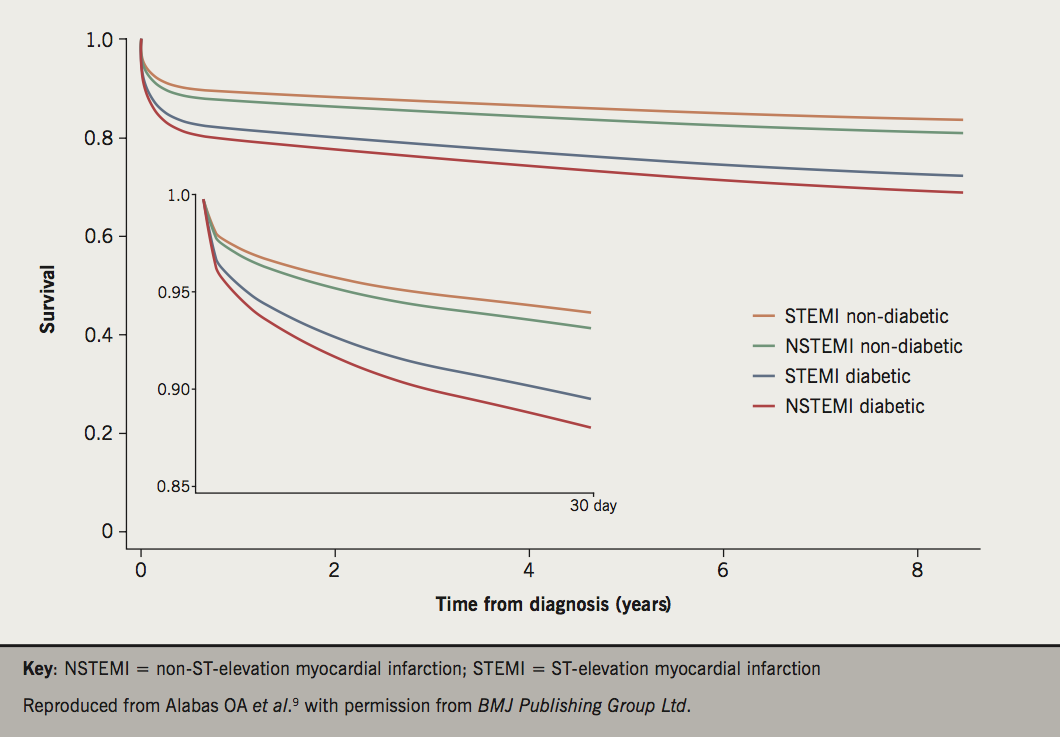

Data from MINAP suggest that between 2003 and 2010 the risk of in-hospital mortality from AMI halved.8 Case fatality rates at 30 days following hospitalisation with AMI, as determined by HES, show similar trends between 2002 and 2010 with a decline from 18.5% to 12.2% in men and from 20.0% to 12.5% in women.6 However, the rates of decline are unequal across age bands, determined by comorbidity, AMI type and associated with the receipt of guideline-indicated treatments (figure 2).9-11 An analysis of 389,057 cases of hospitalised NSTEMI in the UK reported that between 2003 and 2013, unadjusted all-cause mortality at 180 days decreased from 10.8% to 7.6% (unadjusted hazard ratio [HR] 0.968, 95% CI 0.966 to 0.971; difference in absolute mortality rate per 100 patients –1.81, 95% CI –1.95 to –1.67). For coronary heart disease in general, in the UK, death rates have fallen by 73% between 1975 and 2013 (age standardised death rate per 100,000: 469 in 1975 vs. 126 in 2013).12

Despite temporal improvements in outcomes from ACS, mortality rates for this population remain high. According to the BHF Heart Statistics, in 2014, coronary heart disease accounted for 69,163 deaths in the UK, of which the highest numbers for men were for the ages between 75 and 84 years (13,421) and for women for the ages greater than 85 years (13,985).12 In 2012, coronary heart disease was the most common single cause of premature death (death before the age of 75 years) in the UK in men, responsible for about 15% of premature male deaths and 8% of premature female deaths.5

Although all-cause mortality is higher among STEMI than NSTEMI, this is only evident early after the hospital presentation; among those surviving to hospital discharge, case fatality from NSTEMI is higher than STEMI.13 Registry-based studies report a cumulative risk of death following AMI (12.1% at six months vs. 39.2% at four years),14 and there is evidence from randomised and observational data for higher rates of death for NSTEMI compared with STEMI in the longer-term.13,15,16

Nowadays, following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), non-cardiovascular death is more frequent than cardiovascular death.17 This epidemiological shift is emphasised by the burden, among survivors of AMI, of re-infarction, stroke and death, and has greater impact on future healthcare utilisation and lifetime costs when the index AMI occurs at a younger age and/or the patient is higher risk.18 That is, among one-year survivors of AMI aged over 65 years, the crude cumulative rate of death, re-infarction and stroke is about 30%.19

Rates of angiography/primary PCI versus medical management

An invasive coronary strategy for the management of AMI is guideline recommended and associated with improved clinical outcomes. For STEMI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) is the preferred reperfusion strategy, provided it can be performed within the guideline-mandated times, irrespective of whether a patient presents to a PPCI-capable hospital.20 For NSTEMI, compared with a selective invasive strategy, a routine invasive strategy has been shown to improve clinical outcomes and reduce recurrent ACS episodes, subsequent rehospitalisation and revascularisation.21

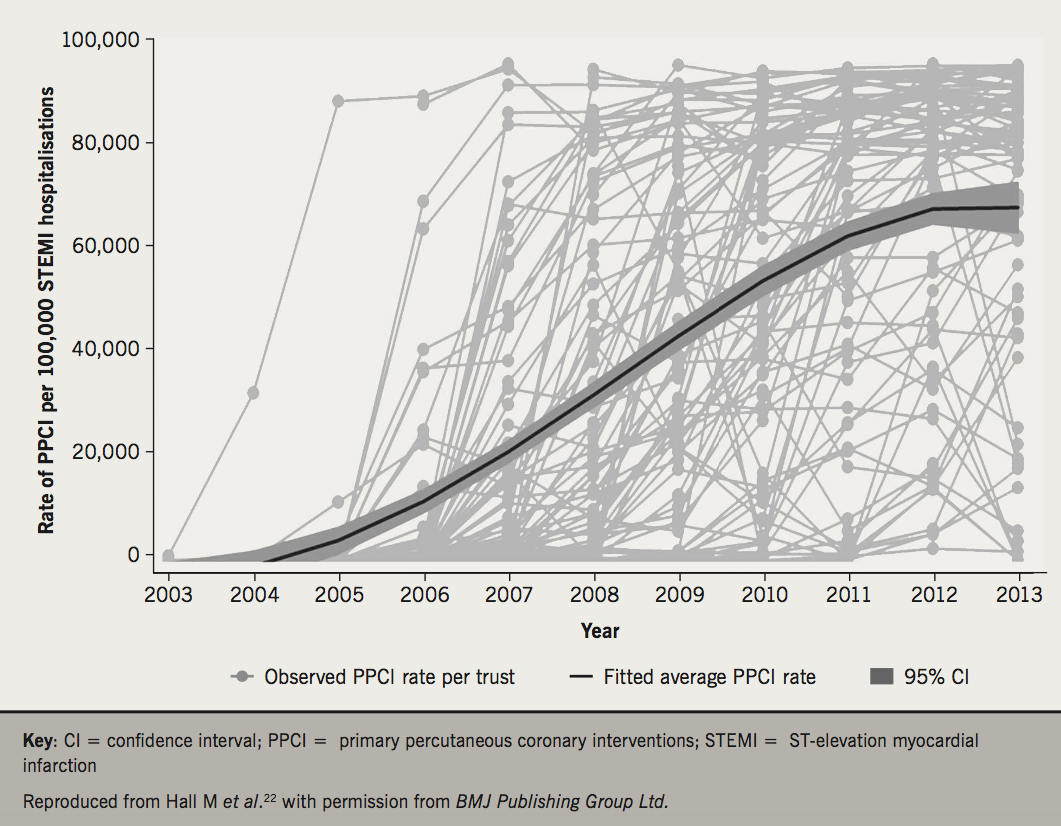

Following an eight-year implementation, the diffusion of PPCI services across the NHS of England has reached a plateau of about 85% of cases of STEMI.22 Analysis of MINAP data suggest a yearly increase in the use of PPCI between 2003 and 2013 of 30% (incidence rate ratio 1.30, 95% CI 1.23 to 1.36) increase in PPCI utilisation (figure 3). However, in this study of 92,350 STEMI hospitalisations, older and sicker patients were less likely to receive PPCI and there was between hospital variation in PPCI rates not attributable to staffing levels. This suggests that PPCI has reached near saturation and only marginal gains in rates of PPCI are likely from hospital reconfiguration. While greater institutional operationalisation of the service through additional infrastructure development and the non-section of cases may improve PPCI utilisation, MINAP data also suggest many patients with STEMI present late to hospital and, therefore, a greater awareness among the public to increase recognition of symptoms and seek urgent medical attention is required.3 Moreover, national data from the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS) national registry of PCI found that the weight of evidence against a centre-volume relationship between PPCI and 30-day mortality was equivalent to the weight of evidence for it.23

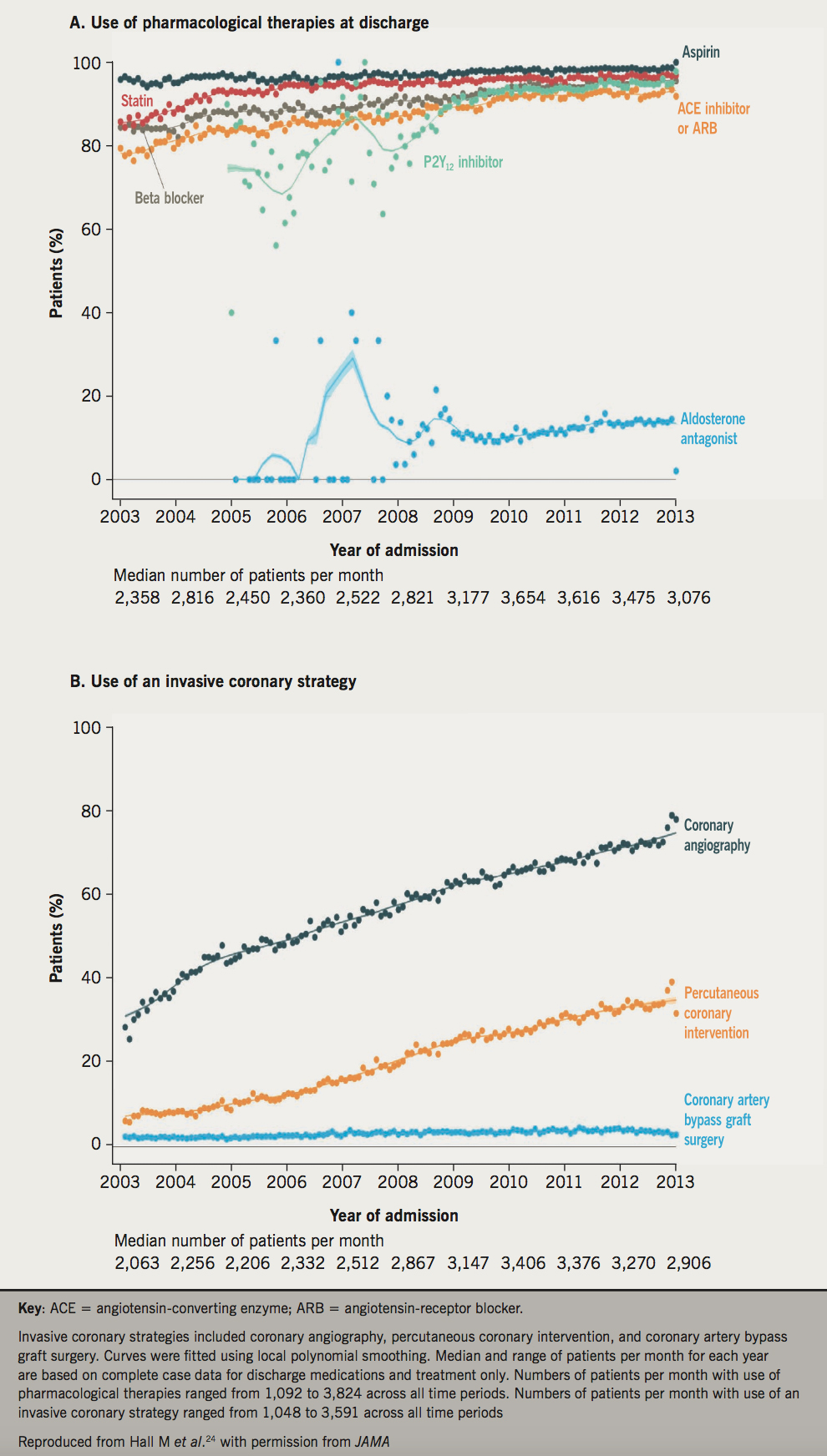

For NSTEMI, there is evidence that an invasive coronary strategy (coronary angiography, PCI and coronary artery bypass graft [CABG]) significantly explained the decline in rates of death in the UK. A UK study of 389,057 patients hospitalised with NSTEMI between 2003 and 2013, who demonstrated an increase in comorbidities and a decrease in predicted atherothrombotic risk, found that only an invasive coronary strategy was significantly associated with the temporal decline in all-cause mortality (figure 4).24 Other UK studies using MINAP data have revealed geographic variation in the provision of NSTEMI care, associated with potentially avoidable deaths.25,26

Risks of re-infarction – who is ‘very high-risk’?

National and international guidelines recommend that as soon as a diagnosis of unstable angina or NSTEMI is made, patients are formally assessed for their risk of future adverse cardiovascular events using an established risk scoring system that predicts six-month mortality.21,27-29 The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) risk score was developed in the GRACE registry programme to assess in-hospital and six-month outcomes of death or non-fatal myocardial infarction.13,30 For these outcomes it was derived and validated in over 42,000 patients with external validation in further separate cohorts. For clinical use, simplified models were derived based upon eight variables to predict the risk of death, or death and non-fatal myocardial infarction (i.e. age, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, Killip class, creatinine concentration, elevated biomarkers of necrosis, cardiac arrest on admission and ST-deviation). These factors conveyed more than 90% of the total risk (c-statistic 0.81 for predicting death and 0.73 for predicting death or non-fatal MI from admission to six months after discharge). The GRACE risk score version 2 has better discrimination, offers an estimate of absolute risk, is suitable for use in hand-held electronic devices/smart phones, and its applicability in the acute setting is broadened by the ability to use substitutions for creatinine and Killip class.31 Whether the use of the GRACE risk score is associated with improvements in the use of guideline-indicated treatments and reduced major adverse cardiovascular events for patients hospitalised with NSTEMI and unstable angina is being investigated in an international randomised controlled trial in the UK (United Kingdom GRACE Interventions Study, UKGRIS) and Australia (Australian GRACE Interventions Study, AGRIS).32

For NSTEMI and unstable angina, high risk is defined according to the 2015 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for the management of ACS in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation, and includes patients with a GRACE risk score greater than 140, or a rise and fall in cardiac troponin compatible with myocardial infarction, or dynamic ST- or T-wave changes.21 Patients defined as high risk include those with haemodynamic instability or cardiogenic shock, recurrent or ongoing chest pain refractory to medical treatment, life-threatening arrhythmias or cardiac arrest, mechanical complications of myocardial infarction, acute heart failure, or recurrent dynamic ST–T-wave changes, particularly with intermittent ST-elevation.

Policies for prevention and their implementation

Increasing and maintaining public and physician awareness of ACS symptoms and treatments is a key to improving care and outcome in this population. Data from the UK suggest that nearly one in three patients with AMI had other diagnoses at first medical contact, who less frequently received guideline-indicated care and had significantly higher mortality rates.33 Other studies have found that the history of chest pain is of limited value in cases of suspected ACS.34,35 While the advent of higher sensitivity troponin assays will ensure that greater numbers of patients with ACS are hospitalised for guideline-indicated care, and without ACS are discharged from hospital, emphasis must be placed on lowering the index of suspicion for ACS in circumstances when its clinical presentation may not be typical.

Clearly, there are local level opportunities to ensure that all patients who have a diagnosis of ACS follow the treatment algorithms recommended by international guidelines. Notwithstanding this, there are patient groups with high rates of subsequent cardiovascular events, including women, the comorbid and those with diabetes, where additional and/or novel health technology innovations are required. In the future, the frail elderly will form a larger proportion of the ACS case presentation, who’s outcomes can be predicted using electronic health records data,36 and who will require care optimisation (that may include deselecting non-appropriate therapies) in an area where there is clinical uncertainty as to the benefits of applying or withdrawing medical interventions (figure 5).37,38

Evaluating and reporting care and outcomes is integral to quality improvement in modern healthcare. Recently, the European Society of Cardiology Acute Cardiovascular Care Association (ESC ACCA) developed a set of AMI quality indicators.39 These measurable indicators are derived from Class 1 Level A treatment recommendations, but also incorporate measures whose implementation is deemed to be important, such as centre facilities and patient satisfaction. They encompass the journey of care for patients with STEMI and NSTEMI and may be used to benchmark the conformity of actual practice with ESC guidelines for the management of AMI. The indicators have been applied to the UK (using MINAP data)40 and separately in France (using the French Registry of Acute ST-Elevation or non-ST-elevation Myocardial Infarction, FAST-MI),41 to show their significant negative association with mortality suggesting, therefore, that greater attainment of the ESC ACCA quality indicators for AMI will reduce deaths from AMI.

Future directions

While huge advances have been made in treatments and outcomes for ACS, such that for those who are optimally managed all-cause mortality rates are low, the increasing age of the UK populace, their associated comorbidities and their enhanced cardiovascular survivorship is creating a population of ACS survivors with recurrent cardiovascular events (figure 6). This, combined with relatively limited advances in science that aim to address long-term cardiovascular outcomes, the introduction of higher sensitivity troponin assays that will potentially increase case detection of AMI, and the non-receipt of optimal ACS care, highlights the scope of the problem.

Addressing the unmet needs of patients with ACS through the application of evidence-based treatments, and the knowledge gap in healthy longevity through the development and use of technologies, pharmacotherapies and available national electronic records of patient data is the necessary next step in cardiovascular medicine for this vulnerable population.

Conflict of interest

CG has received consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Novartis and Vifor Pharma, and speaker fees from AstraZeneca.

Key messages

- Despite a decline in the incidence of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), in the UK there are over 80,000 hospitalisations each year for AMI

- There has been a decrease in the rates of early death associated with AMI but the risk of future fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events following AMI is high

- Across the UK rates of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) are high and rates of PCI for non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) have increased

- The advent of higher-sensitivity troponins will enable improved diagnosis of patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome (ACS)

- Greater awareness about the management of ACS according to risk stratification of predicted future cardiovascular events may improve clinical outcomes for ACS

- Women, those with comorbidities, and the frail elderly, are at higher risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes and require careful optimisation of treatment

- In future, the frail elderly and the multi-morbid will form a greater proportion of the ACS population, where there are many clinical uncertainties as regard to their ACS care

- Quality indicators for AMI have recently been developed. These can be applied to patients with ACS in the UK for the evaluation of care, and their attainment is negatively associated with mortality

- Scientific advances are required to enable a greater understanding of the survivorship trajectories of patients with ACS. Novel healthcare interventions may maintain healthy longevity

References

1. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2551–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs184

2. Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project. How the NHS cares for patients with heart attack. Annual Public Report April 2014–March 2015. London: NICOR, 2017. Available from: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/nicor/audits/minap/documents/annual_reports/08818-minap-2014-15-1.1

3. Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project. How the NHS cares for patients with heart attack. Ninth Public Report 2010. London: MINAP, 2010. Available from: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/nicor/audits/minap/documents/annual_reports/minap2010publicreport

4. British Heart Foundation. CVD statistics – BHF UK factsheet. London: BHF, 2017. Available from: https://www.bhf.org.uk/research/heart-statistics

5. Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe K, Williams J et al. The epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in the UK 2014. Heart 2015;101:1182–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307516

6. Smolina K, Wright FL, Rayner M et al. Determinants of the decline in mortality from acute myocardial infarction in England between 2002 and 2010: linked national database study. BMJ 2012;344:d8059. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d8059

7. Yeh RW, Sidney S, Chandra M et al. Population trends in the incidence and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2010;362:2155–65. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0908610

8. Gale CP, Cattle BA, Woolston A et al. Resolving inequalities in care? Reduced mortality in the elderly after acute coronary syndromes. The Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project 2003–2010. Eur Heart J 2011;33:630–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehr381

9. Alabas OA, Hall M, Dondo TB et al. Long-term excess mortality associated with diabetes following acute myocardial infarction: a population-based cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2017;71:25–32. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2016-207402

10. Gale CP, Cattle BA, Baxter PD et al. Age-dependent inequalities in improvements in mortality occur early after acute myocardial infarction in 478,242 patients in the Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project (MINAP) registry. Int J Cardiol 2013;168:881–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.10.023

11. Gale CP, Allan V, Cattle BA et al. Trends in hospital treatments, including revascularisation, following acute myocardial infarction, 2003–2010: a multilevel and relative survival analysis for the National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (NICOR). Heart 2014;100:582–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304517

12. Townsend NBP, Wilkins E, Wickramasinghe K, Rayner M. Cardiovascular Disease Statistics 2015: British Heart Foundation Centre on Population Approaches for Non-Communicable Disease Prevention. Oxford: Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, 2015.

13. Fox KA, Dabbous OH, Goldberg RJ et al. Prediction of risk of death and myocardial infarction in the six months after presentation with acute coronary syndrome: prospective multinational observational study (GRACE). BMJ 2006;333:1091. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38985.646481.55

14. Tang EW, Wong CK, Herbison P. Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) hospital discharge risk score accurately predicts long-term mortality post acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J 2007;153:29–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2006.10.004

15. Cox DA, Stone GW, Grines CL et al. Comparative early and late outcomes after primary percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-segment elevation and non-ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (from the CADILLAC trial). Am J Cardiol 2006;98:331–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.01.102

16. Darling CE, Fisher KA, McManus DD et al. Survival after hospital discharge for ST-segment elevation and non-ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction: a population-based study. Clin Epidemiol 2013;5:229–36. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S45646

17. Spoon DB, Psaltis PJ, Singh M et al. Trends in cause of death after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation 2014;129:1286–94. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006518

18. Walker S, Asaria M, Manca A et al. Long-term healthcare use and costs in patients with stable coronary artery disease: a population-based cohort using linked health records (CALIBER). Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2016;2:125–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjqcco/qcw003

19. Rapsomaniki E, Thuresson M, Yang E et al. Using big data from health records from four countries to evaluate chronic disease outcomes: a study in 114,364 survivors of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2016;2:172–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjqcco/qcw004

20. Steg PG, James SK, Atar D et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2569–619. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215

21. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2016;37:267–315. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv320

22. Hall M, Laut K, Dondo TB et al. Patient and hospital determinants of primary percutaneous coronary intervention in England, 2003–2013. Heart 2016;online first. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308616

23. O’Neill D, Nicholas O, Gale CP et al. Total centre percutaneous coronary intervention volume and 30-day mortality: a contemporary national cohort study of 427,467 elective, urgent, and emergency cases. Circulation Cardiovascular quality and outcomes 2017;10:e003186. https://doi.org/10.1161/circoutcomes.116.003186

24. Hall M, Dondo TB, Yan AT et al. Association of clinical factors and therapeutic strategies with improvements in survival following non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction, 2003–2013. JAMA 2016;316:1073–82. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.10766

25. Dondo TB, Hall M, Timmis AD et al. Excess mortality and guideline-indicated care following non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2016;online first. https://doi.org/10.1177/2048872616647705

26. Dondo TB, Hall M, Timmis AD et al. Geographic variation in the treatment of non-ST-segment myocardial infarction in the English National Health Service: a cohort study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011600. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011600

27. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Unstable angina and NSTEMI: early management (CG94) Clinical guideline. London: NICE, March 2010 (updated November 2013). www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg94

28. Jneid H, Anderson JL, Wright RS et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline and replacing the 2011 focused update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2012;126:875–910. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0b013e318256f1e0

29. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Acute coronary syndromes in adults. Quality standard [QS68] London: NICE, September 2014. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs68

30. Granger CB, Goldberg RJ, Dabbous O et al. Predictors of hospital mortality in the global registry of acute coronary events. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2345–53. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.163.19.2345

31. Fox KA, Fitzgerald G, Puymirat E et al. Should patients with acute coronary disease be stratified for management according to their risk? Derivation, external validation and outcomes using the updated GRACE risk score. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004425. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004425

32. Chew DP, Astley CM, Luker H et al. A cluster randomized trial of objective risk assessment versus standard care for acute coronary syndromes: rationale and design of the Australian GRACE Risk score Intervention Study (AGRIS). Am Heart J 2015;170:995–1004 e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2015.07.032

33. Wu J, Gale CP, Hall M et al. Impact of initial hospital diagnosis on mortality for acute myocardial infarction: a national cohort study. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2016;online first. https://doi.org/10.1177/2048872616661693

34. Swap CJ, Nagurney JT. Value and limitations of chest pain history in the evaluation of patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2005;294:2623–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.20.2623

35. Carlton EW, Than M, Cullen L et al. ‘Chest pain typicality’ in suspected acute coronary syndromes and the impact of clinical experience. Am J Med 2015;128:1109–16.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.04.012

36. Clegg A, Bates C, Young J et al. Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age Ageing 2016;45:353–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw039

37. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE guideline [NG56]. Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management. London: NICE, September 2016. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng56

38. Bebb OS, Smith FGD, Clegg A et al. Frailty and acute coronary syndrome: a structured literature review. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2017;online first. https://doi.org/10.1177/2048872617700873

39. Schiele F, Gale CP, Bonnefoy E et al. Quality indicators for acute myocardial infarction: a position paper of the Acute Cardiovascular Care Association. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2017;6:34–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/2048872616643053

40. Bebb O, Hall M, Fox KAA et al. Performance of hospitals according to the ESC ACCA quality indicators and 30-day mortality for acute myocardial infarction: national cohort study using the United Kingdom Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project (MINAP) register. Eur Heart J 2017;38:974–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx008

41. Schiele F, Gale CP, Simon T et al. Quality indicators for acute myocardial infarction: rate of implementation and association with 3-year survival. Results from the Nationwide FAST-MI 2005 and FAST-MI 2010 registries. Circ Outcomes and Quality 2017;in press.

close window and return to take test

All rights reserved. No part of this programme may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers, Medinews (Cardiology) Limited.

It shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent.

Medical knowledge is constantly changing. As new information becomes available, changes in treatment, procedures, equipment and the use of drugs becomes necessary. The editors/authors/contributors and the publishers have taken care to ensure that the information given in this text is accurate and up to date. Readers are strongly advised to confirm that the information, especially with regard to drug usage, complies with the latest legislation and standards of practice.

Healthcare professionals should consult up-to-date Prescribing Information and the full Summary of Product Characteristics available from the manufacturers before prescribing any product. Medinews (Cardiology) Limited cannot accept responsibility for any errors in prescribing which may occur.