Studies have suggested that acute coronary syndrome (ACS) may be excluded by a single undetectable high-sensitivity troponin (hs-TnT) taken at least three hours after the onset of symptoms in patients with non-pleuritic chest pain whose electrocardiogram (ECG) is non-ischaemic.

During a six-month period between April and September 2015, we identified 147 consecutive patients with non-pleuritic chest pain and non-ischaemic ECG whose first hs-TnT was less than 5 ng/L at least three hours after the onset of symptoms. We used the Elecsys hs-TnT assay, which has a lower limit of detection of 5 ng/L and a 99th centile of <14 ng/L.

Sixty-seven of 147 (46%) patients were male. The average age of our cohort was 52 years, range 19–83 years. Coronary heart disease (CHD) was known to have been present in 24 (16%) before the index admission. Median length of hospital stay was 15.4 hours (mean 22.5 hours) with 86 (59%) patients spending more than 12 hours in hospital. We referred 60 (41%) patients to cardiology for further assessment, either during or after admission, in order to rule out unstable angina. No patient was readmitted with hs‑TnT positive ACS, one patient underwent elective revascularisation and no patient died during one year of follow-up. Only one patient was lost to follow-up.

In conclusion, patients with non-pleuritic chest pain, non-ischaemic ECG and undetectable hs-TnT at least three hours after the onset of symptoms have a low risk of hs-TnT positive ACS, revascularisation and death during one year of follow-up. Most such patients could safely be discharged from hospital after a few hours of observation, without the need for a second hs-TnT.

Introduction

Most patients presenting as an emergency with chest pain do not have myocardial infarction (MI),1 which must, nevertheless, be ruled out in order to reassure and discharge from hospital. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-TnT) and troponin I (hs-TnI) have streamlined the assessment and management of chest pain, as a rapid rule out of MI is now possible, particularly if hs-TnT or hs-TnI are undetectable at presentation.2-8

Undetectable troponin cannot, however, be used to exclude unstable angina, which by definition is not associated with a troponin rise.9 It is for this reason that physicians and cardiologists may be reluctant to send patients home from the emergency department (ED) without further assessment. Previous studies have shown that the negative predictive value of an undetectable troponin is greater than 99% for MI and cardiac death up to 30 days,2,4-8 with only a few reporting cardiac outcomes up to one year.2,5

The purpose of our study was twofold: to determine the long-term risk of MI, coronary revascularisation and cardiac death by following a cohort of patients with undetectable hs-TnT and a non-ischaemic electrocardiogram (ECG) for a total of one year after their presentation with chest pain; and to explore the possibility that such patients might safely be discharged from hospital after a few hours’ observation.

Method

This was a retrospective study carried out in Dumfries and Galloway Royal Infirmary, a district general hospital covering a population of 147,000 in southwest Scotland. Hs-TnT was requested in 1,920 patients during a six-month period between April and September 2015 and was undetectable in 541 (28%). Using the algorithm shown in figure 1, we examined 308 electronic case sheets, which enabled us to exclude a further 67 patients who had no pain at presentation, 51 patients whose chest pain was pleuritic, 32 patients whose first hsTnT was ≤5 ng/L within three hours of the onset of symptoms, seven patients whose first hs-TnT was ≥5 ng/L and four patients with an ischaemic ECG at presentation. In this way, we were able to identify 147 consecutive patients with non-pleuritic chest pain and normal ECG whose first hs-TnT was less than 5 ng/L.

For each patient, we reviewed the electronic case record for past history of coronary heart disease (CHD), i.e. previous acute coronary syndrome (ACS), coronary revascularisation, stable angina; time between onset of pain and blood draw for hs-TnT; time taken to discharge patient from hospital; whether patient was referred to cardiology for further assessment; and, finally, whether the patient was readmitted with ACS, revascularised or died within one year of their index admission. Linkage to the electronic case records at tertiary centres in Glasgow and Edinburgh, where angiography and revascularisation are undertaken, ensured that no admissions to these hospitals were missed. We considered the admission ECG to be ischaemic with any ST–T wave changes >1 mm, even if present on a previous ECG. In order to measure cardiac troponin we used the Elecsys hs-TnT assay, which has a lower limit of detection of 5 ng/L and a 99th centile of <14 ng/L.

Results

Sixty-seven of 147 (46%) patients with hs‑TnT <5 ng/L were male. The average age of our cohort was 52 years, range 19–83 years. CHD was known to have been present in 24 (16%) before the index admission. Thirty-two (22%) patients had hs-TnT measured once only; 108 (73%) had more than one undetectable hs-TnT; while seven (5%) had initial hs-TnT <5 ng/L and a subsequent hs‑TnT in the range 5–13 ng/L. Intermittent pain in 21 patients made it difficult to determine the precise time between symptom onset and blood draw, though in each of these cases the time between onset of first pain and blood draw was greater than three hours (table 1).

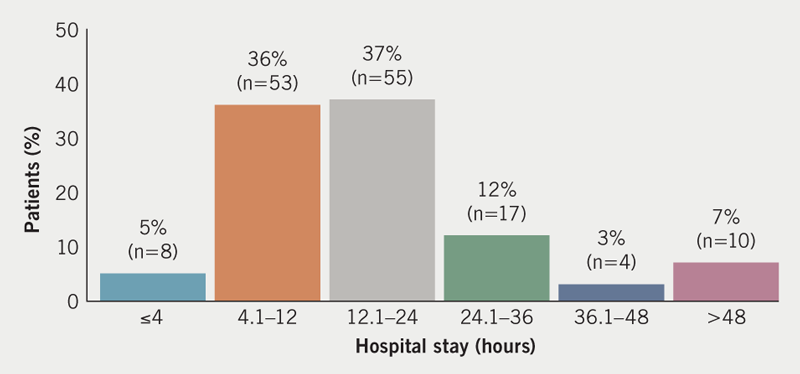

Median length of hospital stay was 15.4 hours (mean 22.5 hours) (figure 2). Only eight patients (5%) were discharged within four hours. Eighty-six (59%) and 31 (21%) patients, respectively, spent more than 12 and 24 hours in hospital. The reasons for a delay in discharge beyond 24 hours were as follows: awaiting consultant review (seven patients), awaiting cardiology team review (six), further inpatient investigations (nine), comorbidities (seven) and procedures (two).

We referred 60 (41%) patients to cardiology for further assessment either during or after admission in order to rule out unstable angina. The outcome of these referrals (numbers in brackets) was as follows: cardiology clinic (33), exercise test (19), echocardiogram (11), 24-hour ECG monitor (eight), stress echo (seven), coronary angiogram (three), computed tomography (CT) coronary angiogram (two), cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (two), thallium-perfusion scan (one). No patient was readmitted with hs-TnT positive ACS, one patient underwent elective revascularisation and no patient died during one year of follow-up. Only one patient, a holidaymaker from the Netherlands, was lost to follow-up.

The clinical details of the seven patients whose first troponin was undetectable and whose repeat was hs-TnT 5–13 ng/L are shown in table 2. Three gave a past history of CHD and five underwent further cardiac investigations, all of which were normal. None were readmitted with MI, required revascularisation or died during follow-up.

Discussion

Our study of 147 patients admitted to a district general hospital in Scotland has shown that the combination of non-pleuritic chest pain with a non-ischaemic ECG and hs-TnT <5 ng/L carries a very low risk of troponin-positive ACS, coronary revascularisation or death during one year of follow-up. This is despite 16% of our patients having coronary disease at the time of presentation. Fifty-nine percent and 21% of patients, respectively, spent more than 12 and 24 hours in hospital. We referred 41% of patients to cardiology for further assessment. The fact that only one patient underwent coronary revascularisation during a year of follow-up suggests that we may have been overly cautious.

Zhelev and colleagues examined the accuracy of a single measurement of the Elecsys hs‑TnT assay in the diagnosis of acute MI in the ED.3 They showed that fewer than one in 100 acute MIs would be missed if 3 ng/L or 5 ng/L is used as the cut-off value. This was despite the fact that many of the studies in their meta-analysis included patients in whom the time from symptom onset to blood draw was less than three hours. Inclusion of such patients is likely to underestimate the sensitivity of the assay. They concluded that a single measurement of Elecsys hs‑TnT <5 ng/L can be used to rule out acute MI, except in patients who present less than three hours after symptom onset.3 This view has been supported by a meta-analysis,10 and endorsed by the European Society of Cardiology in their non-ST-elevation MI (NSTEMI) guideline, which states that a single Elecsys hs-TnT <5 ng/L rules out NSTEMI in patients presenting to the ED with chest pain and a normal ECG, except in those presenting very early, e.g. within one hour from chest pain onset, in whom a second cardiac troponin should be obtained at three hours due to the time dependency of troponin release.11

Similar findings have been reported for hs-TnI. The Chapman meta-analysis of 22,547 patients with suspected ACS in 19 cohorts found hs-TnI less than 5 ng/L in 49% of patients, and that this was associated with a negative predictive value (NPV) of 99.5% for the primary outcome of MI or cardiac death at 30 days.12 Only five per 1,000 patients with hs-TnI <5 ng/L went on to have MI or cardiac death at 30 days. NPVs were higher if patients presenting within two hours of symptom onset and those with ECG evidence of myocardial ischaemia were excluded from the analysis (NPV 99.6% if time of symptom onset to troponin sample >2 hours and NPV 99.7% if less than 2 mm ST depression in two consecutive leads and no new T-wave inversion). The use of lower thresholds than 5 ng/L did not improve diagnostic accuracy in this meta-analysis.12 Essentially similar results have been reported by the studies that contributed to that meta-analysis.2,4-6

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that high-sensitivity troponin measurements are interpreted together with the clinical presentation, time from onset of symptoms, the 12-lead ECG and, additionally, the pre-test probability of NSTEMI. NICE suggest a validated tool such as the thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) score for this purpose.13 This advice has recently been validated in a pooled study of over 7,000 adults presenting to the ED with chest pain and a non-ischaemic ECG. NPVs for 30-day major adverse coronary events (MACE) were greater than 99% for all TIMI scores in the range 0–2, but were highest for TIMI score 0, which the authors felt would identify around 20% patients as low risk and suitable for early discharge.8 Others have shown that the combination of a limit of detection cut-off and a non-ischaemic ECG, in the absence of a clinical risk score, is as effective at ruling out MI, calling into question the added value of clinical risk stratification.2-7,10,12

We addressed the question of early discharge by examining duration of hospital stay for patients with non-ischaemic ECGs and undetectable troponin. Only 4% of these patients were discharged within four hours, suggesting either that clinicians were concerned they might still have unstable angina or that patients had other reasons for staying in hospital. In an attempt to determine the number of patients who might be suitable for early discharge, we found hs-TnT was undetectable in 541/1,920 (28%) patients in whom it was measured. Shah et al.2 and Parsonage et al.7 found undetectable hs-TnI in 649/3,340 (19%) and 943/3,128 (30%) of their patients, respectively. Others have estimated the proportion of patients safe for early discharge based on their troponin values and clinical risk scores,14,15 though we know of no study that has recorded exactly how long patients stayed in hospital and why. Clearly there is potential here for discharging more patients home sooner after documenting an undetectable troponin. Concerns about missing cases of unstable angina could be addressed by referring those who give a history of effort pain to rapid access chest pain clinics.

Our study has strengths and limitations. By reviewing all available electronic casenotes we were able to exclude patients who did not have chest pain and patients whose pain was pleuritic in nature. We were also confident of cardiovascular and other outcomes in all patients except one holidaymaker who was lost to follow-up. We recognise the following limitations. Our study was smaller than many others in this field and retrospective rather than prospective. Moreover, our results are specific for the Elecsys hs-TnT assay and cannot necessarily be extrapolated to other troponin assays, although the results of studies using the hs-TnI assay suggest that similar conclusions would have been drawn.

In conclusion, these data add to accumulating evidence that patients with non-pleuritic chest pain, non-ischaemic ECG and a single undetectable hs-TnT taken at least three hours after the onset of symptoms have a very good prognosis, and can safely be discharged from hospital after a few hours observation, without the need for a second hs-TnT.

Key messages

- Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) may be excluded by a single undetectable high-sensitivity troponin (hs-TnT) taken at least three hours after the onset of symptoms in patients with non-pleuritic chest pain whose electrocardiogram (ECG) is non-ischaemic

- Only 8/147 (5%) of our patients with undetectable hs-TnT were discharged from hospital within four hours

- No patient was readmitted with hs-TnT positive ACS, one patient underwent elective revascularisation and no patient died during one year of follow-up

- More patients could safely be discharged from hospital after a few hours observation without the need for a second hs-TnT

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding statement

This research received no grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Study approval

Ethical approval was not required as there were no patient identifiable data, in keeping with Scottish Health Boards’ policies.

References

1. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation 2012;126:2020–35. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0b013e31826e1058

2. Shah ASV, Anand A, Sandoval Y et al. High sensitive troponin I at presentation in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome: a cohort study. Lancet 2015;386:2481–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00391-8

3. Zhelev S, Hyde C, Youngman E et al. Diagnostic accuracy of single baseline measurement of Elecsys troponin T high sensitive assay for diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in the emergency department: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2015;350:h15. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h15

4. Chapman AR, Anand A, Boeddinghaus J et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of early rule out pathways for acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2017;135:1586–96. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025021

5. Neumann JT, Sorensen NA, Ojeda F et al. Immediate rule out of acute myocardial infarction using electrocardiogram and baseline high sensitive troponin I. Clin Chem 2017;63:394–402. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2016.262659

6. Sandoval Y, Smith SW, Love SA, Sexter A, Schulz K, Apple FS. Single high sensitivity cardiac troponin I to rule out myocardial infarction. Am J Med 2017;130:1076–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.02.032

7. Parsonage WA, Mueller C, Greenslade JH et al. Validation of NICE diagnostic guidance for rule out of myocardial infarction using high sensitive troponin tests. Heart 2016;102:1279–86. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309270

8. Carlton EW, Pickering JW, Greenslade J et al. Assessment of the 2016 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence high-sensitivity troponin rule-out strategy. Heart 2018;104:665–72. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2017-311983

9. Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antnam EM et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/non ST elevation myocardial infarction. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2007;116:e14–e304. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.181940

10. Pickering JW, Than MP, Cullen L et al. Rapid rule-out of myocardial infarction with a single high sensitivity cardiac troponin T measurement below the limit of detection: a collaborative meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:715–24. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-2562

11. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet J-P et al. 2015 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2016;37:267–315. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv320

12. Chapman AR, Lee KK, McAllister DA et al. Association of high sensitivity troponin I concentration with cardiac outcomes in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome. JAMA 2017;318:1913–24. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.17488

13. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chest pain of recent onset. CG95. London: NICE, 2016. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg95

14. Carlton EW, Khattab A, Greaves K. Identifying patients suitable for discharge after a single presentation high sensitivity troponin result: a comparison of five established risk scores and two high sensitivity assays. Ann Emerg Med 2015;66:635–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.07.006

15. Mokhtari A, Lindahl B, Schiopu A et al. A 0-hour/1-hour protocol for safe early discharge of chest pain patients. Acad Emerg Med 2017;24:983–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13224