Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is encountered with increasing frequency in clinical practice,1 and is associated strongly with adverse clinical outcomes, including stroke, cardiovascular events and death.2,3 Concomitant atherosclerotic disease may increase the risk of adverse outcomes in people with AF. For example, peripheral arterial disease was present in 11% of a large cohort of European patients with AF, and increased the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular death, compared with patients with AF but no peripheral arterial disease.4 In addition, AF is associated with adverse outcomes in a range of other subgroups of patients, including those with heart failure.5

Oral anticoagulation is an important component of the management of AF, and has been shown to improve clinical outcomes significantly in this population.6 In recent years, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) have become available.7 We describe the latest findings from two randomised-controlled trials, ENGAGE-AF TIMI-48 (Effective Anticoagulation with Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation – Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction 48)8 and ENSURE-AF (Edoxaban versus Warfarin in Subjects Undergoing Cardioversion of Atrial Fibrillation),9 that evaluated edoxaban, a NOAC acting via antagonism of Factor Xa, in comparison with warfarin. Our main focus will be on the effects of edoxaban in a wide range of patient subgroups, especially those with comorbid cardiovascular disease.

The ENGAGE-AF TIMI-48 trial

Study design

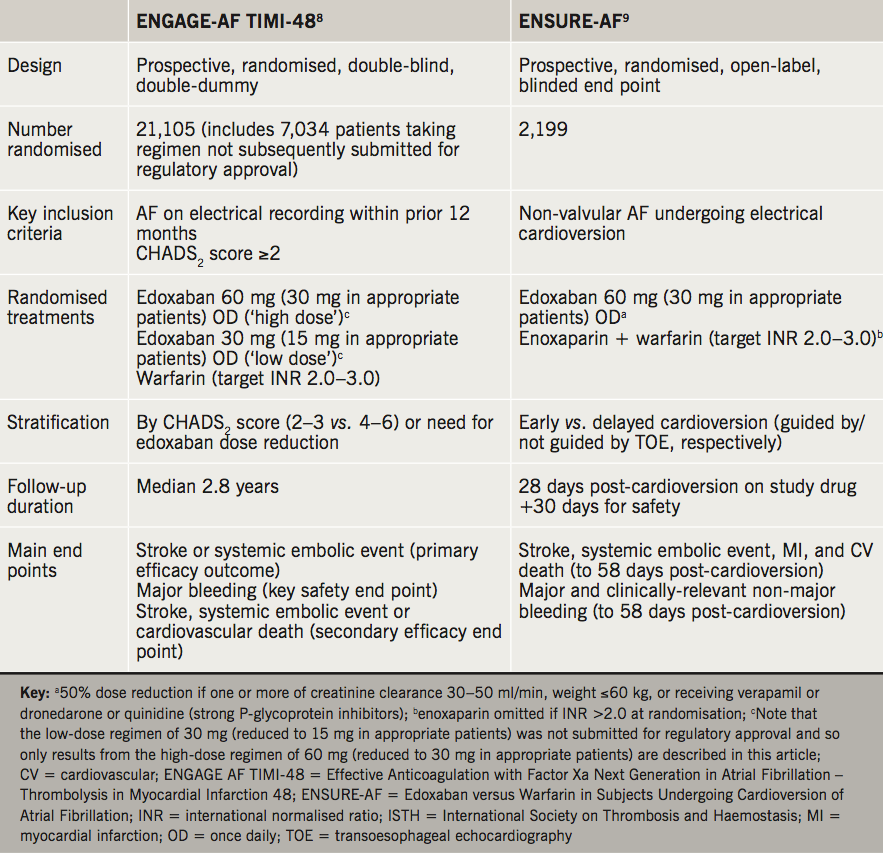

Table 1 summarises the design and patient populations of ENGAGE-AF TIMI-48.8 The trial recruited a population with 21,105 patients with documented AF and risk factors for stroke at randomisation (determined by elevation of CHADS2 score, which is a validated index of risk of stroke in patients with non-rheumatic AF10). Patients were randomly allocated to a higher dose of 60 mg edoxaban (with 50% dose reduction to 30 mg if one or more of creatinine clearance [CrCl] 30–50 ml/min, weight ≤60 kg, or receiving strong P-glycoprotein inhibitors), or lower dose edoxaban 30 mg (with 50% dose reduction to 15 mg for reasons above), or to warfarin (guided by monitoring of INR) for a median follow-up of 2.8 years. The lower dose edoxaban regimen was not ultimately submitted for regulatory approval. Subsequent discussion of edoxaban relates to the approved higher-dose regimen. Note: The current approved dose reduction criteria for edoxaban differ slightly from those used in the ENGAGE-AF TIMI-48 study. The Summary of Product Characteristics states that the edoxaban dose should be reduced from 60 mg to 30 mg if the patient has CrCl 15-50 ml/min, body weight ≤ 60 kg, or is taking the following P-gp inhibitors: ciclosporin, dronedarone, erythromycin, or ketoconazole.

Effects of edoxaban on clinical outcomes in ENGAGE-AF TIMI-48

Main results

Two main analyses were presented for ENGAGE-AF TIMI-48. A modified intention-to-treat (mITT) analysis was designed to assess non-inferiority of edoxaban versus warfarin (the criterion for non-inferiority was an upper 97.5% confidence interval [CI] for the hazard ratio of the primary efficacy end point of <1.38). The primary efficacy end point of ENGAGE-AF TIMI-48 (stroke or systemic embolic event [SSE]) occurred more often in the mITT analysis in patients randomised to warfarin versus edoxaban (hazard ratio [HR] 0.79, 97.5% CI 0.63 to 0.99). This comparison met formal criteria for non-inferiority of edoxaban versus warfarin (p<0.001).

Edoxaban did not achieve superiority over warfarin in the full ITT analysis for the primary outcome (HR 0.87, 97.5% CI 0.73 to 1.04, p=0.08). The main secondary end point (stroke, SSE or cardiovascular death) was reduced significantly by edoxaban (HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.96, p=0.005). Edoxaban reduced the risk of cardiovascular death versus warfarin: HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.97, p=0.01.

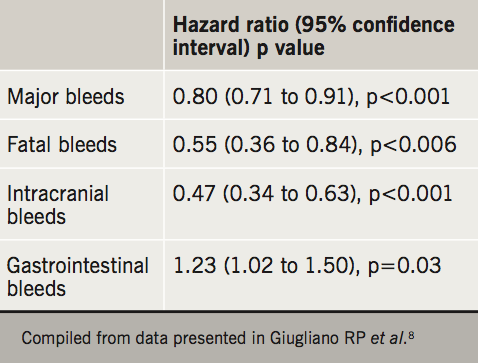

Significantly less major bleeding was observed versus warfarin for edoxaban (HR 0.80, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.91, p<0.001). Significantly lower rates of other adverse bleeding outcomes were seen for edoxaban versus warfarin, although significantly more gastrointestinal bleeds were seen with edoxaban versus warfarin. Selected data on bleeding outcomes for edoxaban versus warfarin are shown in table 2.

Subgroup analyses: insights from patients with established cardiovascular disease

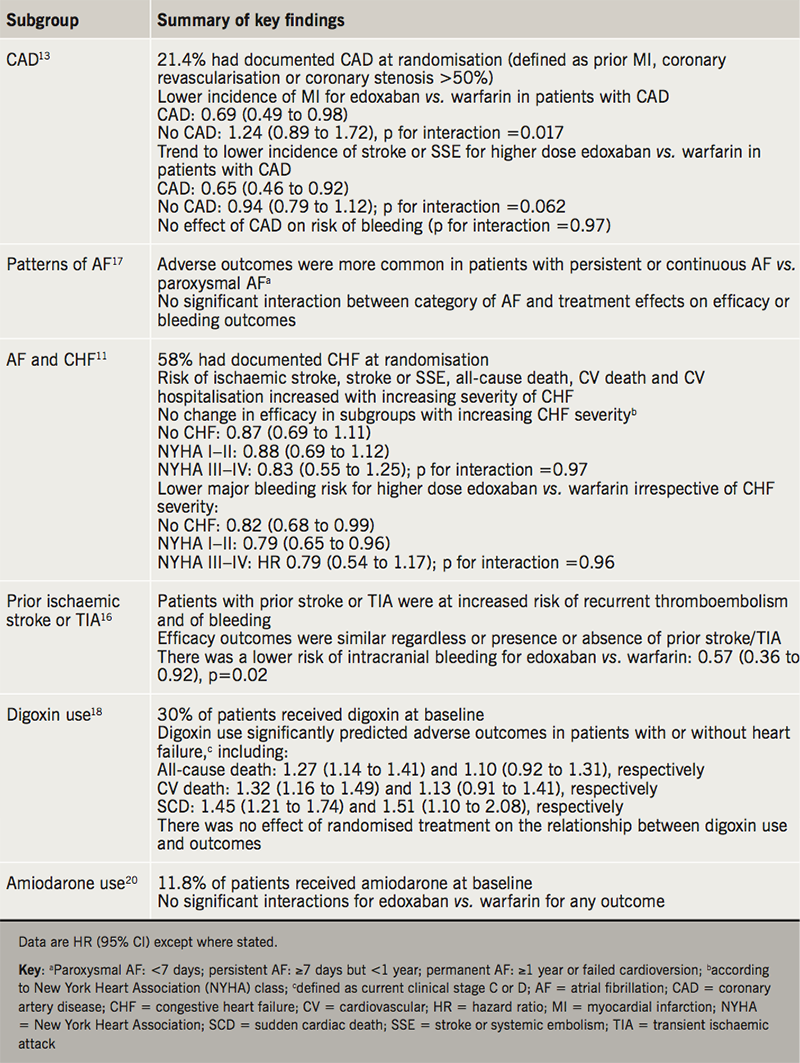

An overview of these important subgroup analyses is shown below and in table 3. More than half of the study population had heart failure at baseline, associated with lower ejection fractions, more severe heart failure symptoms, and greater use of cardiovascular therapies.11 Increasing severity of heart failure predicted adverse outcomes, although heart failure of any severity did not alter the relative magnitude of effect or safety outcomes of edoxaban versus warfarin. These observations are important, as heart failure itself is a prothrombotic state, and associated with reduced time-to-therapeutic range for circulating warfarin concentrations.12

About one-fifth (21.4%) of patients had established coronary artery disease (CAD) at entry to the trial.13 Patients with CAD differed from those without CAD as would be expected (e.g. more likely to be male, more aspirin use, poorer renal function, more risk factors for stroke or bleeding). Edoxaban versus warfarin was associated with significantly reduced risk of myocardial infarction (MI), with a trend towards reduced risk of stroke or SSE. A suggestion of increased risk of SSE, MI, major adverse cardiovascular events and all-cause or cardiovascular death in patients with CAD receiving warfarin was observed in a multi-variate analysis. More frequent treatment interruptions in the warfarin arm, compared with edoxaban, may have contributed to these findings, as interruption of anticoagulation was shown elsewhere to increase the risk of adverse outcomes in this trial.14 The reduced risk of bleeding associated with edoxaban (see above) was preserved irrespective of CAD status.

Concomitant use of single antiplatelet therapy (SAPT) with study treatments was present in 4,912 patients and was associated with higher risk of bleeding, but no additional efficacy against thromboembolic disease.15 The relative efficacy of edoxaban was unaffected and the reduced bleeding outcomes with edoxaban seen in the main trial were preserved in the presence of additional SAPT.

Patients with prior ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack were at increased risk of bleeding and recurrent thromboembolic events.16 The safety and efficacy outcomes for edoxaban use were similar to the whole cohort. Edoxaban reduced the risk of intracranial bleeding in these patients compared with warfarin.

Patients with persistent AF or permanent AF were more likely to experience adverse clinical outcomes compared with those with paroxysmal AF (see footnote to table 3 for definition of AF categories).17 However, there was no significant interaction between AF category and treatment effect.

Digoxin use was associated with increased mortality and other adverse outcomes irrespective of the presence or absence of heart failure, and this relationship was not modified by randomised treatment.18 Although the results were adjusted for clinical variables, the authors note that there is likely to be residual confounding from differences in baseline characteristics, although more so in the heart failure than the non-heart failure subgroups. This finding is interesting in the context of growing concerns regarding risks associated with digoxin use.19

About one patient in 12 received amiodarone at baseline in ENGAGE-AF TIMI-48.20 Amiodarone is a weak inhibitor of P-glycoprotein, with some potential to increase exposure to concomitantly administered edoxaban,21 although no reduction in the dose of edoxaban is required for patients taking these drugs together. Trough edoxaban levels were significantly higher in patients receiving versus not receiving amiodarone in either dose group. However, there was no interaction for any primary bleeding outcome, and no interaction for any efficacy outcome with edoxaban.

Other subgroup analyses from ENGAGE-AF TIMI-48

Peri-operative outcomes: Anticoagulation complicates surgery, and interruption of anticoagulation increases the risk of adverse thromboembolic outcomes.14 Of 7,913 patients in ENGAGE-AF TIMI-48 who underwent surgery (34% of the total population across all arms of the study), anticoagulation was interrupted in 3,116 patients.22 Looking at the results for warfarin versus the licensed edoxaban arm (60 mg with dose reduction to 30 mg in appropriate patients), for patients with interruption of anticoagulant therapy, stroke or systolic embolism occurred in 0.6% on warfarin, and in 0.5% on edoxaban (p=0.53), and major bleeds occurred in 1.0% and 1.2%, respectively (p=0.94). Thus, these data suggest no differences in risk of adverse outcomes with interruption of anticoagulation for surgery according to anticoagulant used. However, the number of events was low after stratification of the population, suspension of anticoagulation was not defined precisely, and the double-blind nature of the trial meant that edoxaban was likely to have been suspended for longer than was necessary.

Age: Stratification of the ENGAGE-AF TIMI-48 population by age showed that in all groups, increasing age increased bleeding risk by more than thromboembolic risk.23 There was no significant interaction between age and study treatment for bleeding and efficacy outcomes, but the higher baseline risk of bleeding in older patients implied greater absolute reduction in bleeding events for edoxaban versus warfarin.23

Risk of falling: Patients at risk of falling, due partly to advanced age and comorbidities such as prior stroke or diabetes, had higher risk of bleeding compared with the overall trial population.24 Thus, although there was no treatment interaction between risk of falling and study outcomes, there was a larger absolute benefit for edoxaban versus warfarin for reduced risk of major bleeding.

Body mass index: Higher body mass index (BMI) in the ENGAGE-AF TIMI-48 population was associated with lower risk of stroke or SSE, or of death, but higher risk of bleeding.25 The effects of study treatments on stroke or SSE, major bleeding, and net clinical benefit were unchanged across BMI categories.

Renal function: The efficacy and safety profile was preserved in patients with reductions in CrCl. However, one subgroup analysis demonstrated a trend towards reduction in efficacy of edoxaban for patients with high CrCl (>95 ml/min).26 However, net clinical benefit for edoxaban was maintained, as rates of bleeding were lower versus warfarin across all CrCl categories.

Malignant disease: Efficacy outcomes were similar in the presence versus absence of malignant disease based on analysis of 1,153 patients who developed a cancer during the study period.27 The authors considered that edoxaban may provide a practical alternative to warfarin in this population, given the challenges with warfarin therapy in this group, including maintaining INR and managing frequent interruptions in therapy for invasive procedures.

Race: Lower trough edoxaban concentrations and anti-Factor Xa activity may have contributed to a lower risk of intracranial haemorrhage and greater improvement in some secondary/tertiary net benefit outcomes in Asian versus other patients; efficacy regarding stroke prevention was preserved.28 Similar findings were reported for East Asian patients.29,30 Efficacy benefits for edoxaban versus warfarin were preserved in patients from Latin America, with a possible greater reduction in intracranial haemorrhage with edoxaban in these patients compared with patients from other regions.31

The ENSURE-AF trial

Study design

ENSURE-AF involved randomisation of 2,199 patients with AF due to undergo cardioversion to either edoxaban 60 mg (dose reduction to 30 mg as described in ENGAGE-AF TIMI-48) or to warfarin ± enoxaparin (depending on INR at randomisation) for 28 days (table 1).9 The primary efficacy outcome was a composite of stroke, SSE, MI and cardiovascular death, assessed from randomisation until 58 days post-cardioversion, and major/clinically relevant non-major bleeding up to 58 days post-cardioversion. Randomisation in ENSURE-AF was stratified according to whether cardioversion was guided by transosesophageal echocardiography (TOE).

Main results and key subgroup analyses

The primary outcome of ENSURE-AF, a composite of stroke, SSE, MI or cardiovascular death, occurred numerically, but not significantly less often in the edoxaban group, compared with warfarin/enoxaparin (odds ratio [OR] 0.46, 95% CI 0.12 to 1.43).9 Similar data were obtained whether patients were stratified for receipt of TOE-guided cardioversion (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.04 to 2.47), or not (OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.08 to 2.36).9

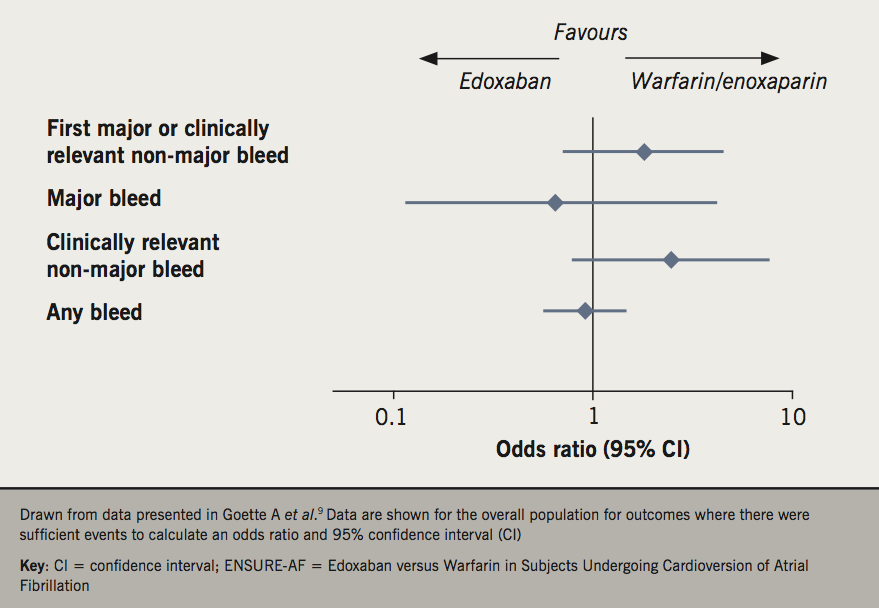

Figure 1 summarises safety outcomes from the overall ENSURE-AF population.9 The number of events was low and the 95% CI for each comparison are wide. Nevertheless, there was no significant excess of any category of bleeding associated with edoxaban treatment.

Several subgroup analyses have been reported from ENSURE-AF:

- BMI: Patients with lower BMI were more likely to achieve successful cardioversion, relative to heavier patients, although the efficacy of edoxaban versus warfarin/enoxaparin did not differ significantly across BMI categories.32

- Risk of stroke or bleeding: Stratification of patients into higher or lower risk scores for stroke (CHADS2-VASc, score >2 vs. ≤2) or bleeding (HAS-BLED, score ≥3 vs. <3) did not affect efficacy outcomes in ENSURE-AF.33 There was a non-significant trend to improved efficacy with edoxaban in the higher CHA2DS2-VASc score group and an opposite trend in the higher HAS-BLED score group. However, the number of end points in some analysis groups was low: there was only one event for CHA2DS2-VASc score ≤2, and only two events for HAS-BLED ≥3.

- Renal function: Odds ratios for efficacy end points did not differ significantly across renal function categories (based on CrCl), although low numbers of events limited this analysis.34

Clinical implications of these studies

The ENGAGE-AF TIMI-48 trial demonstrated non-inferiority for its primary composite outcome of adverse cardiovascular and thromboembolic events with edoxaban compared with warfarin targeted to INR 2.0–3.0. In addition, randomisation to edoxaban was associated with reduced risk of bleeding events compared with warfarin. An extensive series of additional analyses from this trial have shown that the therapeutic profile of edoxaban is comparable irrespective of patients’ age, BMI, renal function, prior cerebrovascular disease history, or ethnicity, among others.

ENSURE-AF is currently the largest evaluation of anticoagulant therapy in patients with AF undergoing cardioversion.35-39 It demonstrated that treatment with once-daily edoxaban was not associated with excess cardiovascular, thromboembolic or bleeding events in the main cohort and subgroups evaluated (although event rates were low and the study was not powered to demonstrate non-inferiority or superiority).

Conclusions

The therapeutic profile of edoxaban is consistent with other NOACs in the management of AF.40,41 It has equivalent efficacy with a reduction in bleeding complications compared with warfarin. The extensive evidence from subgroup analysis supports the clinical use of edoxaban across patients with a wide range of cardiovascular disease, medications, age, frailty, weight and renal function.

Key messages

- Edoxaban was non-inferior to warfarin for preventing adverse cardiovascular and thromboembolic outcomes in the ENGAGE-AF TIMI-48 trial

- The risk of major bleeding, including intracranial bleeding, was lower with edoxaban versus warfarin

- The ENSURE-AF trial demonstrated that edoxaban is an alternative to warfarin/enoxaparin for patients with AF undergoing cardioversion

Conflicts of interest

KK has received honoraria from Bayer, Menarini and Pfizer. HT reports honoraria, sponsorship to attend scientific meetings and project support from all NOAC manufacturers.

Acknowledgement

A medical writer (Dr Mike Gwilt, GT Communications) provided editorial assistance, funded by the British Journal of Cardiology.

Khalid Khan

Consultant Cardiologist

Glan Clwyd Hospital, Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board, Sarn Lane, Rhyl, LL18 5UJ

Honey Thomas

Consultant Cardiologist

Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, Ashington, Northumberland, NE63 9JJ.

Email: honey.thomas@northumbria-healthcare.nhs.uk

Articles in this supplement

Introduction

2. Insights in stroke prevention in patients with a prior history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack

3. Insights in the treatment and prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism

4. Insights from primary care: opportunities and challenges

References

1. Adderley NJ, Ryan R, Nirantharakumar K, Marshall T. Prevalence and treatment of atrial fibrillation in UK general practice from 2000 to 2016. Heart 2019;105:27–33. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2018-312977

2. Johnson DL, Day JD, Mahapatra S, Bunch TJ. Adverse outcomes from atrial fibrillation: mechanisms, risks, and insights learned from therapeutic options. J Atr Fibrillation 2012;4:477. https://doi.org/10.4022/jafib.477

3. Stewart S, Hart CL, Hole DJ, McMurray JJ. A population-based study of the long-term risks associated with atrial fibrillation: 20-year follow-up of the Renfrew/Paisley study. Am J Med 2002;113:359–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01236-6

4. Proietti M, Raparelli V, Laroche C et al. Adverse outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation and peripheral arterial disease: a report from the EURObservational research programme pilot survey on atrial fibrillation. Europace 2017;19:1439–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euw169

5. Mountantonakis SE, Grau-Sepulveda MV et al. Presence of atrial fibrillation is independently associated with adverse outcomes in patients hospitalized with heart failure: an analysis of get with the guidelines-heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2012;5:191–201. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.965681

6. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2893–962. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210

7. Salem JE, Sabouret P, Funck-Brentano C, Hulot JS. Pharmacology and mechanisms of action of new oral anticoagulants. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2015;29:10–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcp.12091

8. Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E et al. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2013;369:2093–104. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1310907

9. Goette A, Merino JL, Ezekowitz MD et al. Edoxaban versus enoxaparin-warfarin in patients undergoing cardioversion of atrial fibrillation (ENSURE-AF): a randomised, open-label, phase 3b trial. Lancet 2016;388:1995–2003. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31474-X

10. Ajam T, Mehdirad AM. CHADS2 score for stroke risk assessment in atrial fibrillation. Medscape Drugs and Diseases 2017. Available at: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2172597-overview [accessed February 2019].

11. Magnani G, Giugliano RP, Ruff CT et al. Efficacy and safety of edoxaban compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure: insights from ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:1153–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.595

12. Ferreira JP, Girerd N, Alshalash S et al. Antithrombotic therapy in heart failure patients with and without atrial fibrillation: update and future challenges. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2455–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw213

13. Zelniker TA, Ruff CT, Wiviott SD et al. Edoxaban in atrial fibrillation patients with established coronary artery disease: insights from ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2019;8:176–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/2048872618790561

14. Cavallari I, Ruff CT, Nordio F et al. Clinical events after interruption of anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation: an analysis from the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. Int J Cardiol 2018;257:102–07. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.01.065

15. Xu H, Ruff CT, Giugliano RP et al. Concomitant use of single antiplatelet therapy with edoxaban or warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: analysis from the ENGAGE AF–TIMI 48 Trial. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5:e002587. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.115.002587

16. Rost NS, Giugliano RP, Ruff CT et al. Outcomes with edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with previous cerebrovascular events: findings from ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 (Effective Anticoagulation With Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 48). Stroke 2016;47:2075–82. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013540

17. Link MS, Giugliano RP, Ruff CT et al. Stroke and mortality risk in patients with various patterns of atrial fibrillation: results from the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial (Effective Anticoagulation With Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 48). Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2017;10:e004267. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.116.004267

18. Eisen A, Ruff CT, Braunwald E et al. Digoxin use and subsequent clinical outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation with or without heart failure in the ENGAGE AF–TIMI 48 trial. JAMA 2017;6:e006035. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.006035

19. Mendell J, Noveck RJ, Shi M. Pharmacokinetics of the direct factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban and digoxin administered alone and in combination. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2012;60:335–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/FJC.0b013e31826265b6

20. Steffel J, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E et al. Edoxaban vs. warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation on amiodarone: a subgroup analysis of the ENGAGE AF–TIMI 48 trial. Eur Heart J 2015;36:2239–45. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv201

21. Mendell J, Zahir H, Matsushima N et al. Drug-drug interaction studies of cardiovascular drugs involving P-glycoprotein, an efflux transporter, on the pharmacokinetics of edoxaban, an oral factor Xa inhibitor. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2013;13:331–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40256-013-0029-0

22. Douketis JD, Murphy SA, Antman EM et al. Peri-operative adverse outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation taking warfarin or edoxaban: analysis of the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. Thromb Haemost 2018;118:1001–08. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1645856

23. Kato ET, Giugliano RP, Ruff CT et al. Efficacy and safety of edoxaban in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation in the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. JAMA 2016;5:e003432. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.116.003432

24. Steffel J, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E et al. Edoxaban versus warfarin in atrial fibrillation patients at risk of falling: ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:1169–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.06.034

25. Boriani G, Ruff CT, Kuder JF et al. Relationship between body mass index and outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with edoxaban or warfarin in the ENGAGE AF–TIMI 48 trial. Eur Heart J 2019;online first. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy861

26. Bohula EA, Giugliano RP, Ruff CT et al. Impact of renal function on outcomes with edoxaban in the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. Circulation 2016;134:24–36. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022361

27. Fanola CL, Ruff CT, Murphy SA et al. Efficacy and safety of edoxaban in patients with active malignancy and atrial fibrillation: analysis of the ENGAGE AF–TIMI 48 trial. JAMA 2018;7:e008987. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.118.008987

28. Chao TF, Chen SA, Ruff CT et al. Clinical outcomes, edoxaban concentration, and anti-factor Xa activity of Asian patients with atrial fibrillation compared with non-Asians in the ENGAGE AF–TIMI 48 trial. Eur Heart J 2018;online first. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy807

29. Yamashita T, Koretsune Y, Yang Y et al. Edoxaban vs. warfarin in east Asian patients with atrial fibrillation – an ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 subanalysis. Circ J 2016;80:860–9. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-15-1082

30. Shimada YJ, Yamashita T, Koretsune Y et al. Effects of regional differences in Asia on efficacy and safety of edoxaban compared with warfarin–insights from the ENGAGE AF–TIMI 48 trial. Circ J 2015;79:2560–7. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-15-0574

31. Corbalán R, Nicolau JC, López-Sendon J et al. Edoxaban versus warfarin in Latin American patients with atrial fibrillation: the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:1466–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.037

32. Lip GYH, Merino JL, Banach M et al. Impact of body mass index on outcomes in the edoxaban versus warfarin therapy groups in patients underwent cardioversion of atrial fibrillation (from ENSURE-AF). Am J Cardiol 2019;123:592–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.11.019

33. Lip GYH, Merino JL, Dan GA et al. Relation of stroke and bleeding risk profiles to efficacy and safety of edoxaban for cardioversion of atrial fibrillation (from the EdoxabaN versus warfarin in subjectS UndeRgoing cardiovErsion of Atrial Fibrillation [ENSURE-AF] Study). Am J Cardiol 2018;121:193–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.10.008

34. Lip GYH, Al-Saady N, Ezekowitz MD, Banach M, Goette A. The relationship of renal function to outcome: a post hoc analysis from the EdoxabaN versus warfarin in subjectS UndeRgoing cardiovErsion of Atrial Fibrillation (ENSURE-AF) study. Am Heart J 2017;193:16–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2017.07.010

35. Nagarakanti R, Ezekowitz MD, Oldgren J et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: an analysis of patients undergoing cardioversion. Circulation 2011;123:131–6. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.977546

36. Piccini JP, Stevens SR, Lokhnygina Y et al. Outcomes after cardioversion and atrial fibrillation ablation in patients treated with rivaroxaban and warfarin in the ROCKET AF trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:1998–2006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.025

37. Flaker G, Lopes RD, Al-Khatib SM et al. Efficacy and safety of apixaban in patients after cardioversion for atrial fibrillation: insights from the ARISTOTLE Trial (Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation). J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:1082–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.062

38. Cappato R, Ezekowitz MD, Klein AL et al. Rivaroxaban vs. vitamin K antagonists for cardioversion in atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2014;35:3346–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehu367

39. Plitt A, Ezekowitz MD, De Caterina R et al. Cardioversion of atrial fibrillation in ENGAGE AF–TIMI 48. Clin Cardiol 2016;39:345–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.22537

40. Caldeira D, Nunes-Ferreira A, Rodrigues R, Vicente E, Pinto FJ, Ferreira JJ. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation: A systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2019;81:209–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2018.12.013

41. Plunkett O, Lip GYH. The potential role of edoxaban in stroke prevention guidelines. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev 2014;3:40–43. https://doi.org/10.15420/aer.2011.3.1.40