Cardiac metastases normally reflect diffuse metastatic spread of the primary tumour and are rarely found in isolation. We present a case of a 71-year-old man with a history of completely resected high-grade spindle cell sarcoma of the left thigh, who presented with shortness of breath, and was found to have a large right ventricular mass, subsequently diagnosed as a metastasis of the prior sarcoma. It was deemed inoperable and incurable, and the patient was offered palliative chemotherapy. Unfortunately, the patient died within four months of his original presentation.

Introduction

Primary cardiac tumours are a rare phenomenon, however, cardiac metastases from extracardiac primaries are found in 10% of all tumour cases, often at autopsy.1 Despite this, patients rarely present with symptomatic cardiac metastases, as they normally reflect diffuse metastatic spread of the primary tumour.2 We present a case of an isolated, aggressive, symptomatic intracardiac metastasis of a recently resected high-grade spindle cell sarcoma of the left thigh.

Case report

|

|

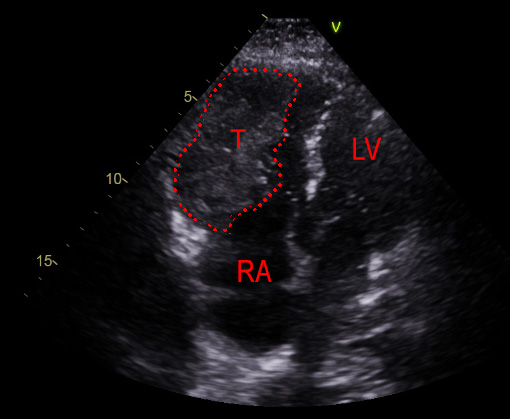

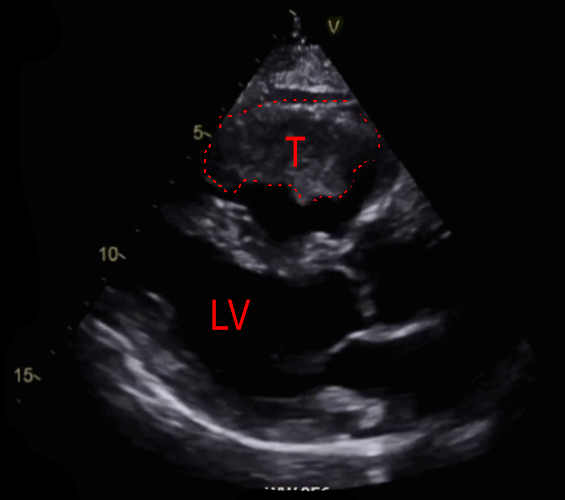

A 71-year-old male ex-smoker presented with a several-week history of progressive exertional dyspnoea, developing rest dyspnoea in the last week. He was seen in a cardiology clinic and an urgent echocardiogram was requested to look for possible heart failure. This revealed a large filling defect in the right ventricle (RV), with significant RV dilation and near obliteration of the RV (figures 1 and 2). In view of these findings, he was admitted into hospital for further investigations. He denied fevers, weight loss, night sweats, syncope, dizziness and chest pain. Prior to admission he was independent in his activities of daily living, and required no mobility aids.

Of note, he had a past medical history of a left thigh high-grade spindle cell sarcoma (pT1N0M0 G3), which was successfully resected eight months prior, requiring no adjuvant radiotherapy. Post-resection magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of his left thigh showed no evidence of sarcoma relapse. A stress cardiac MRI two years prior did not reveal any RV dysfunction or mass. The only other background of note was ischaemic heart disease, with coronary artery stenting in 2012.

On examination, he looked generally well with no signs of fluid overload. His jugular venous pressure (JVP) was 5 cm above the sternal notch. His left thigh showed a previous resection scar with no obvious signs of local sarcoma relapse. There was no suspicious cutaneous lesion.

He had a computed tomography (CT) scan of his chest, abdomen and pelvis, which showed an RV mass extending into the pulmonary outflow tract, and incidental findings of bilateral pulmonary emboli. No other masses or metastases were seen. Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed a first-degree heart block and a right-bundle branch block, neither of which were present on an ECG three years prior. Blood results of note included a raised troponin T of 31 ng/L (normal range 0–14 ng/L).

The patient was reviewed by the cardiothoracic sarcoma multi-disciplinary team (MDT) and a biopsy was recommended. A percutaneous transcatheter biopsy was performed with transoesophageal echocardiographic (TOE) guidance, after which the patient was discharged from hospital. The biopsy revealed a poorly differentiated tumour. Given his past medical history and following review of his previous resection histology, the pathologists felt that the most likely diagnosis was a metastasis from his left thigh high-grade spindle cell sarcoma.

The RV tumour was deemed unresectable by the cardiothoracic sarcoma MDT. The only oncological option available was palliative chemotherapy with liposomal doxorubicin (Caelyx®), although this is associated with a low tumour response rate. The patient was also referred to the palliative care team in view of his poor prognosis. He unfortunately passed away around four months after his original presentation.

Discussion

This case highlights the insidious presentation of a significant intracardiac tumour. Cardiac metastases occur more commonly than primary cardiac tumours.2 Given the recent history of a high-grade spindle cell sarcoma, an intracardiac metastasis is the likely diagnosis. It is worth noting that infra-diaphragmatic origins of cardiac metastases are rare, so are cardiac metastases that are predominantly intracavitary.3 Our case displays both of these features. Of further interest is the fact that cardiac metastases do not usually occur in isolation and they are typically part of generalised tumour spread in a patient.2,3 Therefore, this is an unusual case of an isolated intracardiac metastasis from a high-grade spindle cell sarcoma of the thigh.

Clinical presentations of metastatic tumours of the heart are highly variable, but they are generally asymptomatic, and cases are more often detected at autopsy than in the live patient.4 Often patients will present with symptoms of heart failure, but a wide variety of presentations are possible depending on the tumour size and location, including conduction defects and arrhythmias.

Large, unresectable malignant cardiac tumours have a poor prognosis of less than one year.5 If surgery is not possible, as in this case, the management options include palliative chemotherapy and/or palliative care with symptom relief.

Often cardiac metastasis reflects diffuse malignant spread of the primary tumour and positron-emission tomography CT (PET-CT) is an important tool in locating occult metastases not apparent on a plain CT.6 A PET-CT was considered for this patient, but not performed as it would not guide management or provide additional prognostic information.

Cardiac metastases are present in approximately half of all cases of metastatic malignant melanoma.3 Despite the absence of any suspicious pigmented cutaneous lesion and past history of melanoma, this was considered a possible diagnosis at initial presentation, hence, the need for a biopsy for histological confirmation of diagnosis.

Conclusion

This is a highly unusual case of a solitary, large intracardiac metastasis presenting with symptoms of heart failure, from a previously resected high-grade spindle cell sarcoma. Its presentation was insidious and the initial impression was heart failure. Cases like these are rare, but this case highlights the crucial role of echocardiography in not just quantifying the ejection fraction in a patient with suspected heart failure, but to rule out other causes, such as pericardial effusion, infiltrative disease and cardiac tumours. Cardiac metastasis should also form part of the differential diagnosis of patients with a history of malignancy who present with new symptoms of heart failure. The prognosis of patients with cardiac metastasis is poor and management is generally palliative.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Patient consent

Written and signed consent was gained from the patient.

References

1. Campisi A, Ciarrocchi AP, Asadi N, Dell’Amore A. Primary and secondary cardiac tumors: clinical presentation, diagnosis, surgical treatment, and results. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2022;70:107–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11748-021-01754-7

2. Nova-Camacho LM, Gomez-Dorronsoro M, Guarch R, Cordoba A, Cevallos MI, Panizo-Santos A. Cardiac metastasis from solid cancers: a 35-year single-center autopsy study. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2023;147:177–84. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2021-0418-OA

3. Reynen K. Metastases to the heart. Ann Oncol 2004;15:375–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdh086

4. Bussani R, De-Giorgio F, Abbate A, Silvestri F. Cardiac metastases. J Clin Pathol 2007;60:27–34. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.2005.035105

5. Butany J, Nair V, Naseemuddin A, Nair GM, Catton C, Yau T. Cardiac tumours: diagnosis and management. Lancet Oncol 2005;6:219–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70093-0

6. Lichtenberger JP, Reynolds DA, Keung J, Keung E, Carter BW. Metastasis to the heart: a radiologic approach to diagnosis with pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2016;207:764–72. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.16.16148

7. Hoffmeier A, Sindermann JR, Scheld HH, Martens S. Cardiac tumors. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014;111:205–11. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2014.0205