A 59-year-old woman presented to the emergency room with sudden onset of retrosternal thoracic pain following emotional stress. The electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed T-wave inversions on precordial leads. Her blood analyses demonstrated elevation of myocardial necrosis markers (peak of troponin I of 3.4 ng/ml). Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) findings were consistent with Takotsubo syndrome, accompanied by mild left ventricular dysfunction. The patient underwent invasive coronary angiography revealing a spontaneous coronary artery dissection in the left anterior descending artery and left main artery. A repeat TTE one week later showed complete resolution of the segmental contractility with a full recovery of left ventricular function. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging revealed no abnormalities. The patient was discharged on dual-antiplatelet therapy. A follow-up coronary angiography performed one month later confirmed complete resolution of the dissection. Takotsubo syndrome and spontaneous coronary artery dissection predominantly affect women and share common triggers. This case highlights the often misdiagnosed association and emphasises the specific diagnosis and treatment nuances associated with it.

Introduction

Takotsubo syndrome (TTS) and spontaneous coronary artery disease (SCAD) may present with similar clinical characteristics, such as chest pain, elevated cardiac biomarkers and comparable wall motion patterns on echocardiography. It is estimated that 7% of patients presenting with a provisional diagnosis of TTS have angiographic evidence of SCAD. Angiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are essential tools for the diagnosis of co-existent TTS and SCAD.

Case report

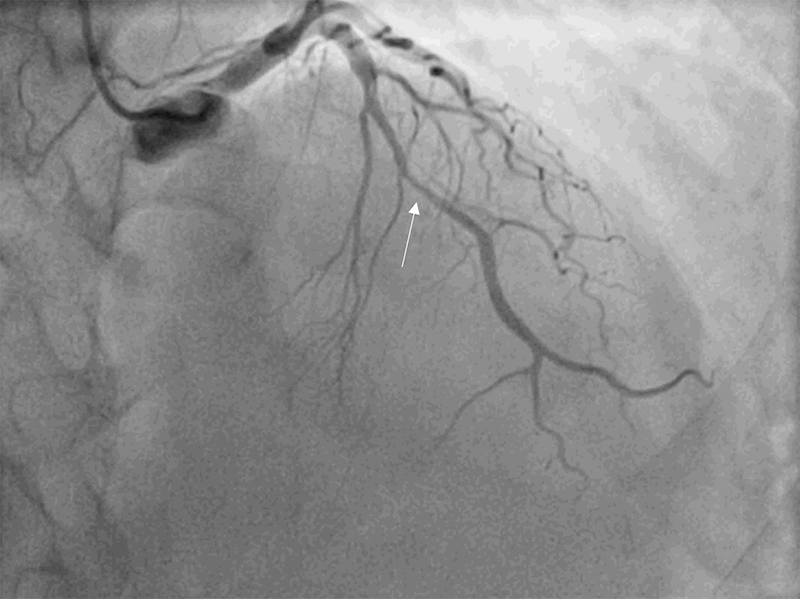

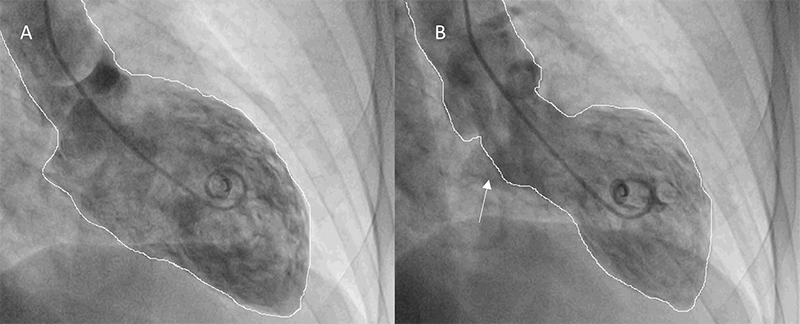

A 59-year-old woman, with a previous history of anxiety and smoking, was admitted for sudden retrosternal pain after an argument with a relative. Physical examination was unremarkable. Electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated T-wave inversion in precordial leads. Blood analyses showed a mild elevation of troponin I (3.4 ng/ml). Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) revealed a left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction of 45% and dyskinesis of all apical segments and the apex with hypercontractility of basal segments. Coronary angiography revealed an intramural haematoma at the mid-segment of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction [TIMI] flow grade 3) (figure 1), and ventriculography confirmed the TTE findings (figure 2). Five days later, TTE showed complete resolution of the wall motion abnormalities with full recovery of LV function. Coronary angiography was also repeated at this time, demonstrating a progression of spontaneous dissection affecting the medium/distal segments of the left main (LM) with a TIMI-3 flow. No intervention was performed. A week later, coronary angiography was unchanged, and cardiac MRI showed preserved biventricular function with resolution of the wall motion abnormalities and no late gadolinium enhancement. As the patient recovered LV wall motion and function, despite the progression of the coronary lesions, this was probably a case of simultaneous TTS and SCAD. The patient was discharged under dual-antiplatelet therapy. A month later, angiography showed complete resolution of the lesion. An immune disease and fibromuscular dysplasia were ruled out. Patient remained under dual-antiplatelet therapy for one year.

Discussion

TTS is characterised by transient LV dysfunction and wall motion abnormalities, typically extending beyond a single coronary distribution in the absence of culprit coronary lesion.1 Nevertheless, coronary artery disease can cause TTS and co-exist in 10–29% of cases. Therefore, coronary angiography with left ventriculography is considered the gold-standard diagnostic tool to exclude or confirm TTS.1 Yet, clear differentiation of TTS and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) may require cardiac MRI.

SCAD is an under-recognised cause of AMI that occurs due to an intimal disruption or intramural haematoma unrelated to atherosclerosis. The LAD is most often affected by SCAD, which may result in LV wall motion abnormalities similar to those observed in TTS.1 It was previously described that SCAD arising from mid to distal LAD, as appears in this case, can compromise the mid-distal anterior and posterior LV wall kinesis, mimicking a TTS. On the other hand, a TTS due to hyperkinesis of the basal LV segments could damage the mid-LAD due to high mechanical stress on the transition point between hyperkinesis and akinesia.1 Another hypothesis is that emotional stress could have triggered both SCAD and TTS simultaneously, as was probably the case here. Misdiagnosis of this association is frequent and may result in mismanagement and undesirable consequences. Therefore, a careful review of coronary angiography is necessary to avoid missed diagnoses, and the use of intravascular imaging tools in inconclusive cases should be considered.1,2 However, it can increase the risk of iatrogenic dissection in patients, and it should only be performed in inconclusive cases.

Finding SCAD in the context of TTS is important, as it changes the need of antiplatelet therapy for SCAD. Treatment of SCAD is still a matter of debate, but it is generally accepted that in patients who are haemodynamically stable/asymptomatic and SCAD involves a distal vessel or its diameter is <3.0 mm, a conservative management should be considered.3 Most cases experience complete recovery within a month. The question regarding whether to perform revascularisation in the setting of SCAD with left main involvement is controversial. Furthermore, there are specific challenges and risks associated with revascularisation in SCAD including high failure rates with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). In the present case, the knowledge that most SCAD heal spontaneously over time, the absence of ongoing chest pain, the absence of ST-segment elevation, and the presence of TIMI-3 flow in LM led to a conservative treatment approach. The patient underwent a period of inpatient observation without complications.

While current guidelines for AMI suggest at least one year of dual-antiplatelet therapy, in patients with SCAD this recommendation seems more controversial. Some experts recommend dual-antiplatelet therapy for at least one year after SCAD, regardless of initial management strategy, along with lifelong aspirin use.4,5 Others opt for no or limited use (one to three months) followed by longer-term aspirin therapy. Most experts recommend aspirin use for at least one year, and frequently indefinitely, after SCAD in patients who receive medical treatment, in the absence of contraindications.4,5 Although long-term prognosis is excellent, the risk of recurrent SCAD events is significant, with an average rate of 5% per year, especially when associated with autoimmune diseases and fibromuscular dysplasia. While it is virtually impossible to declare which occurs first, it appears that each of them may have provoked the other equally.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Patient consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report, including accompanying images.

References

1. Hausvater A, Smilowitz NR, Saw J et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection in patients with a provisional diagnosis of takotsubo syndrome. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8(22):e013581. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.119.013581

2. Buccheri D, Cimino G, Ciotta E. Reconsidering spontaneous coronary artery dissection mimicking takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Interv Cardiol J 2017;3:1. https://doi.org/10.21767/2471-8157.100048

3. Alfonso F, García-Guimaraes M, Bastante T et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: from expert consensus statements to evidence-based medicine. J Thorac Dis 2018;10:4602–08. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2018.07.10

4. Hayes SN, Kim ESH, Saw J et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: current state of the science. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018;137:e523–e557. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000564

5. Abreu G, Galvão Braga C, Costa J, Azevedo P, Marques J. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: a single-center case series and literature review. Rev Port Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2018;37:707–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.repc.2017.07.019