Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery is a rare congenital condition that proves to be fatal in most individuals during childhood due to significant left ventricular ischaemia. However, there are case reports of individuals surviving into adulthood that have varying presenting symptoms. We report a case of a young male, who presented to our cardiology clinic with typical ischaemic cardiac pain, with no established risk factors, and was found to have anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery that was subsequently surgically corrected.

Introduction

Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery is a rare congenital condition that often proves fatal in infants. However, we present a case of a young patient presenting with angina-like chest pains since childhood, who subsequently underwent successful surgical correction resulting in alleviation of symptoms.

Case report

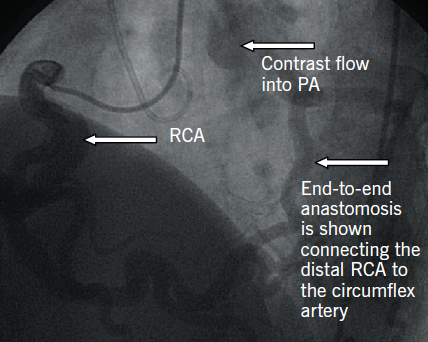

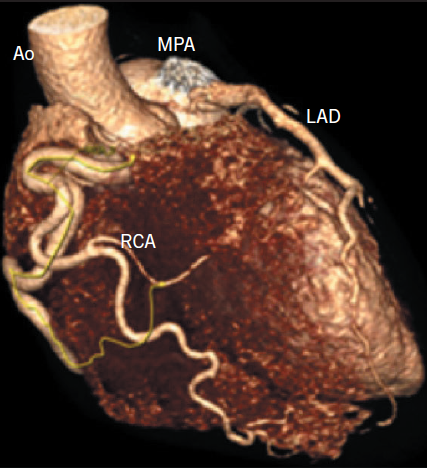

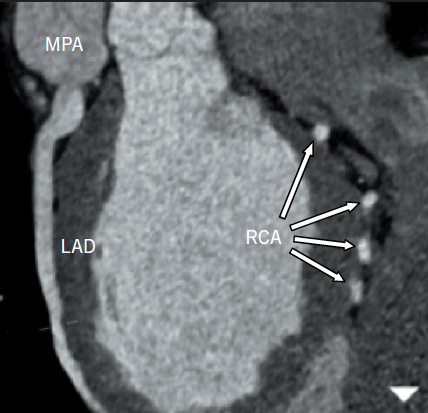

A 25-year-old normotensive, non-diabetic, non-smoker with no family history of ischaemic cardiac disease was referred to the cardiology clinic, by his general practitioner, for progressive exertional chest pains since childhood. Since the clinical scenario did not correlate with a low-risk cardiovascular profile, an exercise treadmill test was performed revealing non-specific ST changes within the anterior leads after nine minutes, with accompanying chest pain. A subsequent stress echocardiogram found a dilated left ventricle (LV) of 6.1 cm at end diastole, normal global systolic function at rest, with hypokinesia of mid and apical anterior wall during peak stress. The evidence of reversible ischaemia led to a coronary angiogram being performed via right femoral artery, revealing a dominant large tortuous right coronary artery (RCA) and, via collaterals, to the left coronary artery (LCA) system, with subsequent retrograde flow into the pulmonary artery (figure 1). An aortogram demonstrated no appreciable LCA origin. This led to a coronary computed tomography (CT) being performed that confirmed the diagnosis of anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA). The large tortuous RCA originated from the aortic root, with the LCA attached to the main pulmonary artery (MPA) (figure 2). A curved planar reformatted CT image confirms the origin of the LCA from the MPA (figure 3).

the aorta (Ao) and the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) attaches to the main pulmonary artery (MPA)

Our patient was referred to and seen at the regional adult congenital heart disease centre. The patient, consequently, underwent a translocated ALCAPA repair with bovine patch and MPA reconstruction in May 2014. The operative findings noted a large dominant RCA with left main stem originating within the lateral aspect of main pulmonary artery 3–5 mm above the post-pulmonary cusp leaflet. The mitral valve was structurally normal. Mild LV systolic impairment with mitral valve insufficiency improved post-operatively. Post-operative recovery was uneventful, with no reported symptoms, and greatly improved exercise tolerance at subsequent outpatient follow-up.

Discussion

ALCAPA is a rare congenital cardiovascular defect with an estimated incidence of one in 300,000 live births, however, this may be an underestimate considering patients may die prior to diagnosis.1 The true incidence of older patients is not known, with only case reports of patients older than 50 years of age.2,3

Krause4 and Brooks5 first described anomalous arteries from the pulmonary artery in 1865 and 1885, respectively, from post-mortem examinations. Brooks5 went on to propose that the LCA had retrograde direction of blood flow to the pulmonary artery. ALCAPA may also be known as Bland, White and Garland syndrome after a published report of the constellation of symptoms, electrocardiographic (ECG) changes, and confirmation of ALCAPA on post-mortem examination of an infant.6

Symptoms are secondary to LV ischaemia due to retrograde flow of blood from the RCA, then via collaterals to LCA with draining into the pulmonary artery (PA). Therefore, the foetus is protected from LV ischaemia, as systemic and pulmonary arterial pressures are equal intra-uterine allowing anterograde flow down both left and right coronary arteries. However, during the neonatal period, pulmonary pressures decrease, and together with ductus arteriosus closure, result in an increase in systemic arterial pressure reversing the blood flow within the LCA retrograde into the PA. The severity of symptoms reflects the degree of myocardial ischaemia and is dependent on the extent of the collateralisation between RCA and LCA, with greater collateralisation leading to less myocardial ischaemia, resulting in fewer symptoms and increased survival. Therefore, explaining the spectrum of symptoms from death during infancy to survival into adulthood.7

Clinical presentation is often non-specific, ranging from angina, syncope, arrhythmias and exertional fatigue to nocturnal dyspnoea. A review found 66% of patients had symptoms of angina, dyspnoea, palpitations or fatigue: 17% presented with ventricular arrhythmia, syncope, or sudden death and 14% of patients were asymptomatic.1

ECGs often show lateral ischaemia or evidence of previous anterior myocardial infarction with presence of Q waves in as many as 50% of patients, and left ventricular hypertrophy is seen in up to 28%, with 4% of patients having a normal ECG.1 A dilated RCA with retrograde Doppler flow from LCA to PA with visualisation of septal flow due to collaterals have been described as diagnostic echocardiographic criteria for ALCAPA.8 However, normal echocardiograms may be seen in 10% of patients, and the presence of ischaemia in stress ECG or imaging, such as in our patient, is well documented.1

Coronary angiography alludes to the diagnosis, with the presence of a large tortuous RCA with collaterals filling the LCA system, as seen with our patient (figure 1). Non-invasive imaging modalities, such as cardiac CT and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), allow visualisation of the origin of the LCA from the PA, dilated tortuous RCA and collateral arteries, with cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) having the advantage of being able to assess myocardial viability and ischaemia.9 Figures 2 and 3 show CT images of our patient confirming the diagnosis of ALCAPA.

Surgical correction is the treatment of choice in suitable patients and has been shown to improve chronic cardiac ischaemia, with encouraging post-operative long-term survival in infants undergoing surgical ALCAPA correction of 94.8%10 and 92%,11 with only a handful of case reports reporting survival after ALCAPA surgical repair in adults. On both three- and six-month follow-up, our patient reported no symptoms with greatly improved exercise tolerance.

Conclusion

ALCAPA is a rare condition. A high index of suspicion is required. Coronary angiography may allude to the diagnosis, however, cardiac CT or MRI is a requisite for diagnostic confirmation. Surgical correction is the treatment of choice, with a frank discussion of risk and benefits being considered on an individual-patient basis. Long-term studies are limited but suggest good outcome.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

1. Yau JM, Singh R, Halpem EJ, Fischman D. Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery in adults: a comprehensive review of 151 adult cases and a new diagnosis in a 53-year-old woman. Clin Cardiol 2011;34:204–10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/clc.20848

2. Separham A, Aliakbarzadeh P. Anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery presenting with aborted sudden death in an octogenarian: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2012;6:12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-6-12

3. Fierens C, Budts W, Denef B, Van De Werf F. A 72 year old woman with ALCAPA. Heart 2000;831:e2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/heart.83.1.e2

4. Krause W. Uber den Ursprung einer akzessorischen A. coronaria aus der A. pulmonalis. Z Rat Med 1865;24:225–9.

5. Brooks HS. Two cases of an abnormal coronary artery of the heart arising from the pulmonary artery: with some remarks upon the effect of this anomaly in producing cirsoid dilatation of the vessels. J Anat Physiol 1885;20:26–9.

6. Bland EF, White PD, Garland J. Congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries: report of an unusual case associated with cardiac hypertrophy. Am Heart J 1933;8:787–801. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0002-8703(33)90140-4

7. Shivalkar B, Borgers M, Daenen W, Gewillig M, Flameng W. ALCAPA syndrome: an example of chronic myocardial hypoperfusion? J Am Coll Cardiol 1994;23:772–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0735-1097(94)90767-6

8. Yang YL, Nanda NC, Wang XF et al. Echocardiographic diagnosis of anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery. Echocardiography 2007;24:405–11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8175.2006.00406.x

9. Pena E, Nguyen ET, Merchant N, Dennis G. ALCAPA syndrome: not just a pediatric disease. Radiographics 2009;29:553–65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1148/rg.292085059

10. Lange R, Vogt M, Horer J et al. Long-term results of repair of anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;83:1463–71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.11.005

11. Azakie A, Russell JL, McCrindle BW et al. Anatomic repair of anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery by aortic reimplantation: early survival, patterns of ventricular recovery and late outcome. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;75:1535–41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0003-4975(02)04822-1