Bifurcation lesions are complex, technically difficult, have a higher rate of adverse events and lower success rates. This has led to the introduction of dedicated bifurcation stents, generally deployed along with main-vessel stent. Cappella Sideguard® is a dedicated bifurcation stent for treatment of bifurcation lesions, which otherwise could be technically challenging and may have low success rates. We report a very interesting case that resulted in a unique complication following the use of a dedicated bifurcation stent.

Case report

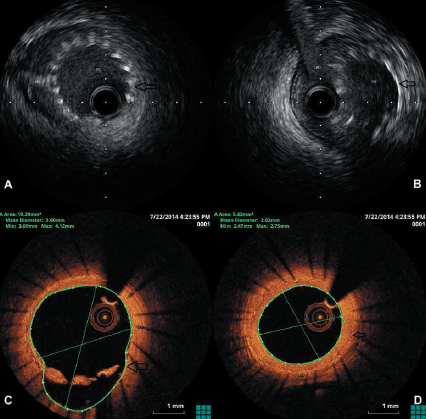

A 43-year-old male with a past medical history of severe asthma and transient ischaemic attack presented with exertional angina and a normal electrocardiogram (ECG). Coronary angiography demonstrated minor plaque disease in the proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD) and ostial lesion in the first diagonal (D1), which was difficult to visualise clearly despite multiple images. As the patient continued to be symptomatic despite medical treatment, he was admitted for further assessment of the LAD and D1 with a view to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), if required. A CLS 3.5 guide catheter was used, the LAD and D1 wired, and intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) performed, as a fractional flow reserve (FFR) study was contraindicated due to his severe asthma. IVUS demonstrated mild plaque disease in proximal LAD, which did not require PCI, but significant stenosis in the ostial D1, with a geometry suitable for a dedicated side-branch stent. The D1 lesion was prepared with Maverick 3 by 9 mm balloon, and stented with Sideguard® stent (3 by 10 mm). Post-procedure IVUS confirmed good apposition of the stent in D1 (figure 1A), although a small section of the cup of stent appeared to be protruding into the main vessel in a non-obstructive manner (figure 1B). The patient made an uneventful recovery and was discharged. He represented with anginal symptoms after three years and was admitted for assessment of his coronary arteries. Angiographically, the LAD had minor plaque disease as previously seen, and the ostium of D1 was patent, but there was new disease distally in the LAD. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of LAD demonstrated the measured length of Sideguard® stent in LAD to be 5.9 mm, suggesting it had migrated backwards and become endothelialised in the main vessel, while the D1 ostium was widely patent (figures 1C and 1D and video below). In addition, there was extensive atheroma in the distal LAD, the most significant portion of which was successfully treated with a drug-coated balloon through the Sideguard® (please see OCT video below). The disease immediately adjacent, but distal to the Sideguard® struts in the distal LAD, was not treated. The patient was discharged on dual antiplatelet medication and remains asymptomatic.

Discussion

Bifurcation lesions are complex, technically difficult, have a higher rate of adverse events and lower success rates.1 This has led to the introduction of dedicated bifurcation stents, generally deployed along with main-vessel (MV) stent. Sideguard® is a self-expanding nitinol stent that flares proximally at the ostium of the side branch (funnel shaped) and conforms to the shape of the lumen, producing late positive remodelling due to ongoing stent expansion (figure 2).

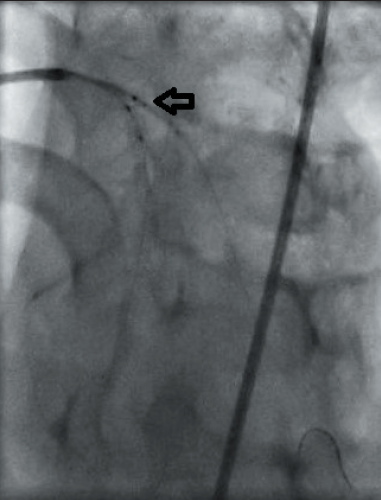

deployed Cappella Sideguard® (black

arrow)

Our patient, despite having an optimum result with Sideguard®, re-presented with angina three years post-PCI. OCT confirmed migration and endothelialisation of Sideguard® into LAD with a patent D1. Coronary stent dislodgement and migration has been described before and the incidence is approximately 0.3–8.3%,2 but this complication in the context of Cappella Sideguard®, to our knowledge, has never been reported previously. We can, therefore, only speculate on the mechanism. The stent in D1 was well-apposed, as confirmed by the IVUS examination (the position of which was unaltered after the procedure) (figure 3), however, the Sideguard® was deployed unaccompanied by a MV stent, which if present may have provided the required anchoring, thereby, preventing the migration of this self-expanding stent. As we have mentioned previously, there was also minimal protrusion of the stent into the MV at the end of the procedure. A combination of these factors may have been responsible for the shifting of the stent. However, isolated Sideguard® deployment has also been performed in six other patients in our institution, but none have presented with a similar complication. Therefore, making it a very unique and multi-faceted problem, which in turn raises issues about its treatment.

Sideguard® is made of nitinol, which would return to its pre-defined shape and size despite ballooning. Stenting would result in a double-layer of metal with potential problems of re-stenosis and thrombogenicity long term. In this case, it was felt that the lesion downstream was responsible for his symptoms and, hence, treated and the patient became asymptomatic.

Conclusion

The future implications of this complication are unclear, as there is a likelihood of atheroma progression distal to Sideguard®, which now acts as a flow divider. This unique case highlights potential problems with dedicated side-branch stents when deployed without MV stent, raising issues of subsequent treatment.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

1. Lefevre T, Chevalier B, Louvard Y. Is there a need for dedicated bifurcation devices? Eurointervention 2010;6(suppl J):J123–J129. http://dx.doi.org/10.4244/eijv6supja20

2. Tekleyes FG, Lester MD, Studeny MA et al. An unusual migration of a stent: a case report. Marshall Journal of Medicine 2016;2:32–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.18590/mjm.2016.vol2.iss2.9