A 61-year-old East European woman was admitted with atypical chest pain. Risk factors: smoker of 5–10 cigarettes per day, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and family history of ischaemic heart disease. Highly sensitive troponin-T, electrocardiogram (ECG) and exercise stress test were normal.

Five months later, the patient reported continuing on/off episodes of minimal exertional shortness of breath and intermittent atypical chest pain. Echocardiogram and coronary angiography were arranged.

Echocardiograph showed a preserved left ventricular systolic function. Ejection fraction: 55% with mild anterior septal hypokinetic wall.

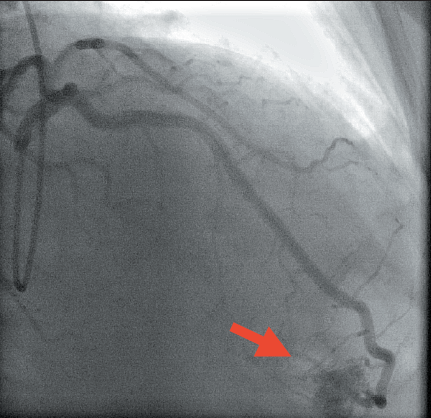

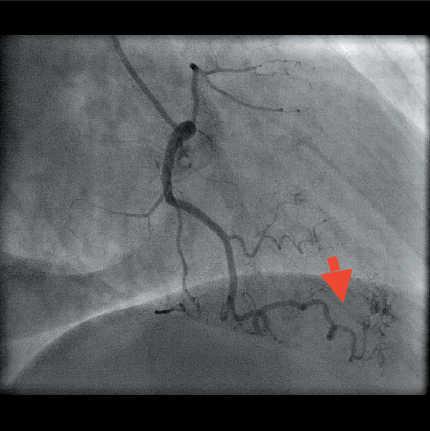

Coronary angiography: left main stem (LMS) and dominant left circumflex (LCx) were normal. The left anterior descending (LAD) artery was normal, however, the distal part appeared to drain toward the right ventricle (RV). A recessive right coronary artery (RCA) had a moderate calibre and tortuous acute marginal branch running toward the apex with minimal contrast spill-out at its end into the RV (figures 1 and 2).

Angiography indicated the presence of LAD and RCA fistulae to RV.

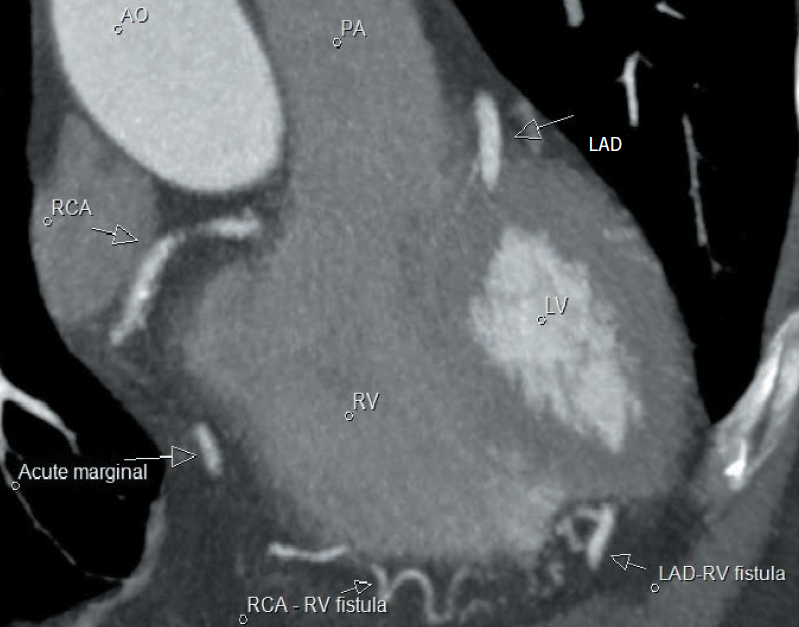

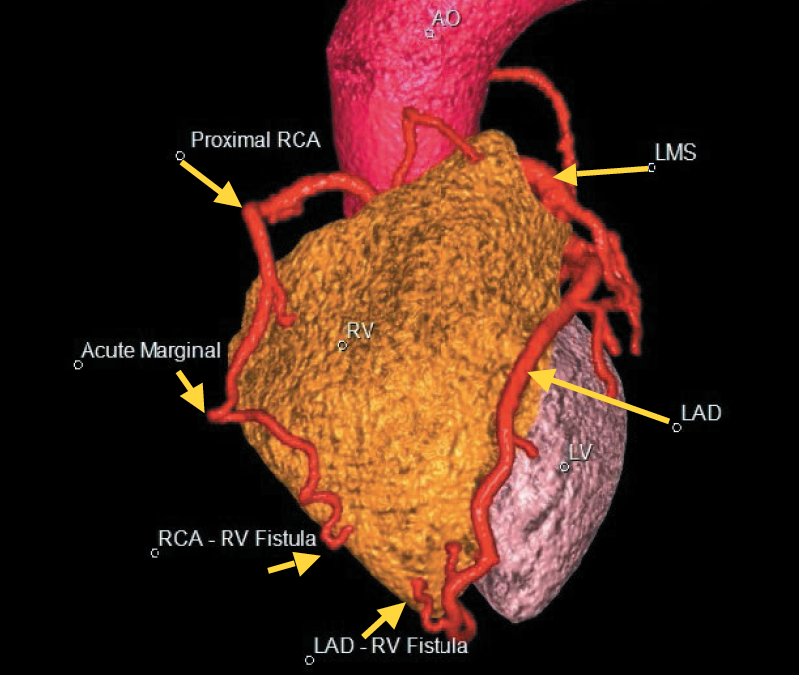

Cardiac-gated computed tomography (CT) coronary angiogram (CTCA) confirmed a tortuous distal LAD and acute marginal branch culminating as a cluster of tiny vessels around the RV apex with blushing of small amount of contrast into the RV apex. The CT findings confirmed the small LAD and RCA fistulae to the RV (figures 3 and 4).

Discussion

A coronary cameral fistula (CCF) is a rare anomalous connection between a coronary artery and a cardiac chamber.¹ CCFs are defined as single or multiple, small or large direct communications that arise from one or more coronary arteries and enter one of the four cardiac chambers.² Of patients diagnosed with solitary CCF, 40% have arterial flow into the RV.

The majority of CCFs are congenital, although a small number are acquired (e.g. coronary artery bypass surgery or myocardial biopsy).³ CCF are usually incidental findings: 0.1% of coronary angiography patients.

Patients with CCFs are usually asymptomatic. However, some patients present with atypical chest pain and/or exertional shortness of breath, depending on the fistula’s size.4

In patients with CCFs and an absence of coronary artery disease (as in this patient), the mechanism of the atypical chest pain/shortness of breath is caused by coronary steal phenomenon.

The majority of patients need no intervention and have good long-term prognosis unless the fistula size has a haemodynamic significance. Symptomatic patients tend to undergo transcatheter closure of the fistula or surgical ligation.

Conclusion

Coronary angiography can provide incidental diagnosis of CCF. It can evidence the dimensions, structure, number, inauguration and concluding point of the fistulae. CTCA is valuable to appraise the composition and depict the course of the CCF.

This patient remains stable with minimal symptoms. In view of this, it was deemed appropriate that conservative management of the CCF occur with annual review.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

1. Vavuranakis M, Bush CA, Boudoulas H. Coronary artery fistulas in adults: incidence, angiographic characteristics, natural history. Catheter Cardiovasc Diagn 1995;35:116–20. http://doi.org/10.1002/ccd.1810350207

2. Said SA, Schiphorst RH, Derksen R, Wagenaar LJ. Coronary-cameral fistulas in adults: acquired types (second of two parts). World J Cardiol 2013;5:484–94. http://doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v5.i12.484

3. Brito FS, Vianna CB, Caixeta AM et al. Single coronary arteries: two cases with distinct and previously undescribed angiographic patterns. J Invasive Cardiol 1999;11:430–4.

4. Dresios C, Apostolakis S, Tzortzis S, Lazaridis K, Gardikiotis A. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy associated with multiple coronary artery–left ventricular fistulae: a report of a case and review of the literature. Eur J Echocardiogr 2010;11:E9. http://doi.org/10.1093/ejechocard/jep196