Computed tomography (CT) is a widely available imaging modality and artefactual findings are not uncommon, particularly in the presence of foreign bodies.

We conducted a retrospective analysis of all CT scans carried out in our trust in a 12-month period, identifying all reports containing the word “pacemaker”. There were 88 scans identified, six of which reported findings related to the pacemaker. In five cases right ventricular lead perforation was reported. All patients underwent further investigations, which did not show any evidence of true lead perforation.

In conclusion, it is important that both cardiologists and radiologists are aware of the possibility of artefactual lead perforation on CT.

Introduction

There has been a significant increase in the use of computed tomography (CT) imaging over the last 20 years, both in terms of the number of patients being imaged and the number of imaging studies per patient. Between 1997 and 2006 the incidence of CT scanning in the US has more than doubled.1

A consequence of increased use is the detection, in increasing numbers, of incidental findings and artefacts.2 An artefact is defined as any discrepancy between what is identified on the CT image and the true appearance of the object.3 Detection of incidental findings and artefacts are particularly prevalent in patients with metallic foreign bodies,4 for example when imaging permanent pacemaker leads.5 The imaging of such leads can be challenging, first, as the heart and the leads are in motion, and, second, as the material is prone to produce streak or ‘star’ artefact.3

Insertion of a permanent pacemaker is a common procedure, with several thousand implanted in the UK each year. It is estimated that one in 50 over 75 year olds have an inserted pacemaker.6 These figures are also on an upward trend, accelerated by the growing popularity of cardiac resynchronisation therapy for patients with ventricular dyssynchrony and severely reduced left ventricular function. Of note, observational data report that defibrillator leads are associated with a more significant artefact effect than with a standard pacemaker lead.4,7

Cardiac perforation of pacemaker leads represents an uncommon complication, but one that provokes significant concern. Historically, the rate of perforation of pacemaker leads has been estimated at less than 3%.8 In 2007, Hirschl et al. studied the prevalence of asymptomatic pacemaker lead perforations on CT, and reported a surprisingly high rate of 15% for atrial leads, 6% for standard ventricular leads and 14% for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) leads.9

When lead perforation is detected it often leads to emergency hospital admission, as well as consideration of lead extraction and replacement.5,10 It is, therefore, a serious clinical incident if a cardiac perforation of pacemaker lead is incorrectly reported on imaging, and every measure should be employed to avoid this, while still ensuring true lead perforations are not missed.

Materials and method

After multiple incidents of incorrect reporting of lead perforation on CT scans in our institution, we sought to undertake a retrospective analysis to investigate the burden of the issue, and explore ways to reduce these incidents. A key word search was used to interrogate the CT database across two hospital sites. All CT scan reports in a 12-month period that contained the word “pacemaker” were included. Reports were then studied and evidence of any artefact or perforation documented. Routine rule-out tests included review of CT with radiologist, echocardiogram and full pacing parameter assessment.

Results

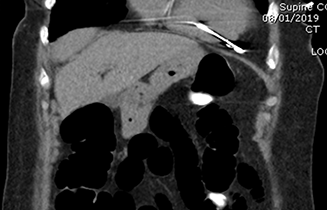

There were 88 scans identified in one year. Six relevant cases were detected. This included two CT thorax scans, two CT colonograms and two CT thorax, abdomen and pelvis scans. Five of these patients had CT scans which reported right ventricular (RV) lead perforation (figure 1). Of these, four patients were admitted to hospital acutely due to these findings. All five patients underwent further investigations, including echocardiography and pacemaker parameter assessment, with one patient undergoing a gated cardiac CT. These investigations did not show any evidence of true lead perforation. All were subsequently followed-up for at least six months with no complications.

Discussion

It is paramount that when patients with permanent pacemakers undergo CT scans every effort is made to avoid incorrect reporting of lead perforations to avoid undue distress.

As noted in our study, there is a higher rate of artefact and false suggestion of lead perforation when scans are not gated, or when the cardiac chambers are not the focus of the scan, for example in a CT colonogram.3,4,8

Clearly true perforations can occur, most commonly within the first year of implant.11 The risk of perforation can be reduced by avoiding placement near the right ventricular free wall.8,10 If perforation is suspected, it is important to review the patient and assess for any symptoms, as well as involving the multi-disciplinary team.10 Reassuringly, however, it is widely agreed that asymptomatic perforation does not require treatment, even if confirmed to not be an artefact.10

Box 1. Recommendations if perforation is seen on computed tomography (CT)

|

|---|

We suggest the following procedure if a CT reports a perforation (box 1). Initially, if possible, review the CT scan with a specialist radiologist, who will have more experience in differentiating between artefact and true perforation. Depending on the outcome of this review and local availability, consider arranging electrocardiography-gated non-contrast cardiac CT imaging, which will have improved specificity at detection of perforation.3 To further reassure the clinician, and ensure adequate pacing function, a pacemaker check should be arranged. Concerning features on a pacing check would include a reduction in R-wave or a change in the capture threshold, injury current or lead impedance.

Finally, to review the pacing leads in real time, as well as assessing for any complications such as pericardial effusion, an echocardiogram should be arranged. Chest radiograph imaging is not useful and has poor sensitivity and poor interobserver agreement.3

Hirschl et al. studied the rates of asymptomatic pacemaker perforation on CT, reporting a surprisingly high rate of 15%.9 All patients in this study had normal pacemaker checks, leading the authors to conclude that asymptomatic perforation rarely results in electrophysiologic consequences. We ponder whether it is possible that some of the reported perforations could have been false-positive findings.

Conclusion

There is currently minimal literature on artefactual lead perforation on CT imaging. It is important that radiologists continue to pay vigilance to lead position when reporting all imaging modalities to ensure that perforation is not missed.11,12 However, efforts must also be made to avoid unnecessary distress and use of emergency admission resources if a lead perforation is queried. As described, even when not artefactual, treatment for an incidentally detected, chronically perforating lead is not always necessary.9,10

In an era of rapidly increasing use of cardiac imaging, collaboration between the specialties remains important.13 Both cardiologists and radiologists should be aware of the possibility of artefactual lead perforation in order to practise prudent healthcare that is in the best interest of the patient.

Key messages

- Artefactual pacemaker lead perforation on computed tomography (CT) imaging is previously undescribed but not uncommon

- Identification of such artefact is an unavoidable consequence of increased use of imaging

- It is clearly of vital importance that genuine perforation is not missed

- Artefactual findings may negatively affect patient experience and prudent healthcare

- It is important that both cardiologists and radiologists are aware of this potential issue

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None.

Study approval

This project was discussed with the local research and development department. We were advised formal ethical approval was not required as the project was considered to be a service evaluation only.

References

1. Smith-Bindman R, Miglioretti DL, Johnson E et al. Use of diagnostic imaging studies and associated radiation exposure for patients enrolled in large integrated health care systems, 1996–2010. JAMA 2012;307:2400–09. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.5960

2. Kelly ME, Heeney A, Redmond CE et al. Incidental findings detected on emergency abdominal CT scans: a 1-year review. Abdom Imaging 2015;40:1853–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-015-0349-4

3. Balabanoff C, Gaffney CE, Ghersin E, Okamoto Y, Carrillo R, Fishman JE. Radiographic and electrocardiography-gated noncontrast cardiac CT assessment of lead perforation: modality comparison and interobserver agreement. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2014;8:384–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcct.2014.08.004

4. DiFilippo FP, Brunken RC. Do implanted pacemaker leads and ICD leads cause metal-related artifact in cardiac PET/CT? J Nucl Med 2005;46:436–43. Available from: http://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/46/3/436.long

5. Barrett JF, Keat N. Artifacts in CT: recognition and avoidance. Radiographics 2004;24:1679–91. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.246045065

6. Bradshaw PJ, Stobie P, Knuiman MW, Briffa TG, Hobbs MS. Trends in the incidence and prevalence of cardiac pacemaker insertions in an ageing population. Open Heart 2014;1:e000177. https://doi.org/10.1136/openhrt-2014-000177

7. Ay MR, Mehranian A, Abdoli M, Ghafarian P, Zaidi H. Qualitative and quantitative assessment of metal artifacts arising from implantable cardiac pacing devices in oncological PET/CT studies: a phantom study. Mol Imaging Biol 2011;13:1077–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11307-010-0467-x

8. Mahapatra S, Bybee KA, Bunch TJ et al. Incidence and predictors of cardiac perforation after permanent pacemaker placement. Heart Rhythm 2005;2:907–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.06.011

9. Hirschl DA, Jain VR, Spindola-Franco H, Gross JN, Haramati LB. Prevalence and characterization of asymptomatic pacemaker and ICD lead perforation on CT. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2007;30:28–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.2007.00575.x

10. Chao JA, Firstenberg MS. Delayed pacemaker lead perforations: why unusual presentations should prompt an early multidisciplinary team approach. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci 2017;7:65–8. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5151.201951

11. Haque MA, Roy S, Biswas B. Perforation by permanent pacemaker lead: how late can they occur? Cardiol J 2012;19:326–7. https://doi.org/10.5603/CJ.2012.0059

12. Kirchgesner T, Ghaye B, Marchandise S, Le Polain de Waroux JB, Coche E. Iatrogenic cardiac perforation due to pacing lead displacement: imaging findings. Diagn Interv Imaging 2016;97:233–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diii.2015.03.011

13. Parwani P, Lopez-Mattei J, Choi AD. Building bridges in cardiology and radiology: why collaboration is the future of cardiovascular imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;11:1713–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.10.004