Traditionally, radial artery access (RAA) has been an exclusively ‘physician-delivered’ service, but with adequate training, nurse-led arterial cannulation can become widely adopted. In this clinical audit, senior nursing practitioners with at least two years of catheter lab experience, were offered RAA training. In phase 1 of training, two nurses were initially familiarised with a well-structured training protocol. Each of the two nurses carried out the first 50 RAA procedures under supervision on elective patients. In phase 2, candidates independently performed 100 procedures. The success and complication rates of these procedures were evaluated prior to their sign-off as competent. The procedural efficacy of nurses was compared with medical registrars of the department to assess the measures of patient satisfaction and time elapsed prior to the insertion of sheath.

During the first 100 directly observed RAA procedures, nurse 1 and nurse 2 achieved success rates of 84% (42/50 procedures) and 86% (43/50 procedures), respectively. During the second phase, nurse 1 achieved a success rate of 82% (82/100 procedures), whereas nurse 2 achieved a success rate of 97% (97/100 procedures). Overall, a success rate of 88% was achieved in the first 300 patients. No significant complications were noted. In contrast to medical registrars, nurse-led cannulation was associated with a greater extent of patient satisfaction, reduced pain intensity (p<0.001), and decreased patient-on-table to sheath insertion intervals (p<0.001). During embedding of the programme, the two nursing practitioners trained additional nurses. Of the five nurses that subsequently entered into training, two have successfully completed both training phases while a further three have completed phase 1. To date, an overall success rate of 91.1% (1,307/1,435 procedures) has been documented.

In conclusion, a nurse-led RAA program is feasible, with satisfactory success rates, no significant complications, and improved rates of patient satisfaction.

Introduction

While undertaking percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) at a tertiary-care cardiology suite, radial artery access (RAA) has demonstrated the advantage of reduced bleeding-related complications as compared with the traditional femoral artery access.1 The utilisation of RAA has significantly increased, with a majority of UK hospitals adopting this approach as the preferred method. The National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (NICOR) national dataset reported that in 2015, up to 80.5% of cases were undertaken via the RAA route, which was a significant rise from 2004 (10.2%).2 Compared with femoral angiography, radial access is a more technically challenging procedure, since the radial artery is a smaller conduit. Moreover, the artery carries an increased propensity to spasm, and could possess a convoluted anatomy. Thus, the rate of trans-radial access failure is significantly high at 6.8%.3 Nevertheless, the radial approach is now considered the gold standard due to the lower rate of vascular complications.4,5 Additionally, the trans-radial approach results in a shorter length of hospital stay and minimal utilisation of hospital resources.6 Despite the technical challenges implicated in radial access, the interventional training has not been standardised, with trainees ‘learning on the job’, potentially through trial and error.7

The medical and nursing professions are continually evolving, driven by the need to improve patient care, address financial limitations, and incorporate technological advancements.8 To address these demands, medical roles have undergone expansion, leading to the assumption of greater responsibilities by nursing personnel. Historically, the performance of arterial cannulations has been a physician-led task, owing to technical intricacies and associated risks of complications.9,10 However, the conventional roles in healthcare are challenged when cannulation is delayed due to scarcity of medical practitioners. Evidence demonstrates that diversification of skills among healthcare professionals can promote continuity of care, leading to improved patient outcomes.11,12 The utilisation of nurse-led vascular access services for the insertion and removal of peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) lines have been widely established across the UK.13 The existing literature reports a technical feasibility of 89% for radial access performed by nurses, with no significant complications reported in the literature.7

Arterial access is an advanced practice undertaken by registered nurses who have undergone specialised training and clinical assessment.14 Nurse-led RAA has been performed at numerous healthcare centres across the globe, including Logan Hospital in Australia, where a successful programme was established to train nurses in arterial line insertion in intensive care units (ICU).15 At the Austin Hospital in Australia, up to 21 ICU nurses were trained in establishing radial access.16 The potential benefits of vascular access performed by nurses include an enhanced quality of nursing care, improved patient experiences, and the release of medical staff to ensure completion of documentation, planning of future care, and comprehensive safe handover, as well as reduced waiting times between cases.17,18 Despite this, peer-reviewed data on nurse-led arterial cannulation are scarce.16,19

This audit aimed to assess the efficacy of a nurse-led service, to analyse radial access time and to investigate the potential complications associated with RAA. The current study is potentially expected to contribute to the scarce body of literature in the domain of nurse-led interventions among critically ill patients.

Method

Participants

This project was commenced in 2018 and involved an audit of catheterisation procedures conducted by the senior catheter laboratory nurses and trained medical practitioners at the Royal Free Hospital. For nurses, inclusion criteria involved an evidence of a sound theoretical knowledge of the procedure, a minimum of two years of catheter lab experience, and a clinical level equivalent to band six or above. Nurse banding in the UK refers to the system used to categorise nursing staff based on their qualifications, experience, and responsibilities under the Agenda for Change (AfC) pay structure.

Additionally, trainee cardiology registrars included medical practitioners of all grades who were rotating into the department, specialty trainees, and senior clinical fellows. Medical practitioners with a cumulative catheter lab experience of 24 months and a satisfactory background knowledge of catheter intervention were shortlisted for comparison with the nursing staff.

Training programme

The training programme was developed by three authors (DW, MA and JGC) and approved by the new practice committee before initiating training in 2018. The training programme comprised three phases: an initial training phase, a second phase including independent performance of the procedure on unselected patients, and an embedding phase where the trained, independent nursing practitioners entered into support service becoming supervisors.

Phase 1

In the primary phase, a comprehensive training programme was devised. The participating nurses were instructed about the training pathway, while they were also educated regarding the normal course of the radial artery and its potential anatomical variations (appendix 1). Moreover, the participants were introduced to a standardised approach regarding artery palpation and anaesthesia, interventional complications and their specific management, and consent plan (Training Manual detailed in appendix 2).

Appendix 1. Developing a nurse-led radial artery access (RAA) servicez

| A nurse-led RAA standard operating procedure (SOP) and education programme was developed. Key considerations for the development of a nurse-led RAA service It is only appropriate to develop the nurse-led service if:

Key contents of the standardised operating procedure

Once the standardised operating procedure was approved by the new procedures committee, a hospital-led programme of education and training was developed. |

Appendix 2. Training manual for radial artery access

| Equipment requirements | |

| Sterile gloves and personal protective equipment | Patient sterile drapes |

| Local anaesthetic: 2% lignocaine | Radial access needle |

| Terumo wire | Radial access sheath |

| Scalpel | Adhesive dressing |

| ChloraPrep | Orange safety needle |

| Procedure | Rationale |

| Complete the WHO Checklist (BEFORE starting procedure) to ensure: 1. Correct patient and procedure 2. Consent is signed and dated by the patient (done in IRCU/Day Ward) 3. Identify important comorbidities 4. Check drugs (loaded DAPT, not on oral anticoagulants) and allergies 5. Bloods (especially Hb, platelets, INR, other bleeding disorders) |

To maintain patient safety and help reduce complications |

| Ensure radial arterial access is safe and appropriate for planned procedure | Radial access is not appropriate for graft cases, or those who require 8F access |

| Ensure patient is well positioned with palm facing upwards and arm is secure with well supported wrist. Remove any rings or bangles | To ensure adequate radial access |

| Wash your hands using aseptic technique Put on a sterile gown and sterile gloves Clean the skin with appropriate cleaning solution (ChloraPrep) Prepare aseptic field |

To prevent infection |

| Inform the patient that you are going to give ‘something to numb the area’ Infiltrate 2–4 ml of 2% lignocaine around the radial artery at the chosen site of access, using a fine bore needle, ensure the superficial and deeper tissues both are infiltrated Massage the lignocaine gently so it spreads through the tissues. Wait 1–2 minutes for anaesthetic to start working |

To ensure patient understanding cooperation and continued consent |

| Use “terumo” needle (part of the arterial radial access set) and by palpitating the artery, puncture the radial artery through the front wall and then the back wall At this point you will already have seen flashback |

|

| Take the needle out and leave the plastic catheter in Prior to inserting the guidewire, check once more that the flexible end is being placed in the sheath, by pressing the guidewire against the back of the operator’s hand that is stabilising the sheath Slowly withdraw the plastic IV catheter until you get pulsating blood flow back and then advance the guidewire as long as there is no resistance |

To prevent dissection of arterial wall during wire insertion |

| Advance the wire slowly ensuring no resistance is felt | If the wire does not advance without resistance you may need to do a more proximal puncture and at this point you need to let the medical practitioner know that there is some resistance while inserting the wire |

| If the wire has advanced, remove the plastic catheter | |

| Now make a small incision using the scalpel | Be careful in making this incision so as not to damage the artery |

| This is done at the puncture point to allow smooth insertion of the radial sheath | Some operators prefer to make an incision straight after giving the local anaesthetic |

| Using the guidewire, the radial sheath plus dilator unit is now advanced safely into the artery, there should be no significant discomfort and limited resistance | |

| Once in place remove the guidewire and the dilator together | |

| Place an adhesive dressing over the sheath hub | To retain it in position during the procedure |

| The sheath can either be five French or six French | Five French sheaths have the advantage in angiography of creating less spasm and the catheters that they admit are smaller in diameter. For angioplasty some operators will switch over to a six French sheath |

Subsequently, candidate nurses performed their first 50 procedures under direct supervision on elective patients with readily palpable radial arteries. A comprehensive audit encompassing cannulation attempts, any difficulties encountered, quality of patient experience, and the overall success rates was undertaken. Only two attempts to cannulate the artery were permitted, while a root-cause analysis was conducted where cannulation was unsuccessful, or any complications arose (appendix 3).

Appendix 3. Criteria to undertake nurse-led RAA

|

Cath lab nurses require sound basic theoretical knowledge to be able to perform this procedure. It was agreed by the senior nursing and medical team that to undertake RAA nurses must have substantial catheter lab experience, generally more than two years. There is little evidence to quantify how much practice is required to become competent at radial arterial access, but the following were proposed: 1. The nurse should be an experienced catheter laboratory practitioner, with a sound working knowledge of vascular access and its complications in the setting of interventional procedures; able to recognise adverse events and understand the principles of their diagnosis and management; aware of their limitations and when and how to seek help. 2. To achieve competency, the practitioner should complete 50 procedures under direct consultant-led observation in a reasonable timeframe, not exceeding 24 weeks. An intermediate assessment of the practitioner’s role is advisable at approximately 12 weeks or less, as required. 3. During training, a comprehensive log of procedures performed, difficulties encountered, and adverse events should be recorded and countersigned by the supervising consultant. 4. The bulk of training procedures (no less than 20) should be supervised by the mentoring consultant, who should only sign off practitioner as competent having reviewed the entire log and discussed any issue raised with the consultant supervising that procedure. 5. Once competent regular practice is required to maintain the skills, we would recommend a minimum of two procedures per working week. 6. Once the practitioners become competent, they must remain up-to-date regarding the latest developments in the clinical domain of radial access. |

Phase 2

After completing the first 50 procedures, all audit data were reviewed to determine if the candidate could perform unsupervised cannulation. The second phase involved the candidate performing a further 100 procedures on unselected cases, with a record of the same audit parameters being obtained. The success and complication rates of the phase 2 procedures were evaluated prior to sign off as an independent practitioner (appendix 3).

Embedding practice

Once the first two nurse practitioners were fully trained, they provided training for radial access, replicating the education on radial artery cannulation and guiding additional nurse practitioners through the same training programme.

Outcomes

The primary study outcome was complication-free procedural success, defined as radial access secured within two puncture attempts and without adverse events. Furthermore, adherence to protocol, number of attempts undertaken, patient satisfaction or complaints, success rates, and adverse event rates were recorded. Secondary outcomes involved estimation of time intervals spanning from the point of patient-on-table to the insertion of sheath, and from the injection of local anaesthetic to sheath insertion. A dedicated nursing team member was formally appointed to time the procedures.

In addition, patient experience was assessed using an anonymised satisfaction questionnaire. The final end points included the number of first-pass cannulations, number and proportion of failed cannulations (failure to cannulate on two attempts), vascular trauma or spasm leading to failure of cannulation by a more experienced operator, patient pain score by operator type, complications prior to discharge, and analysis of efficiency impact of nurse-led radial artery cannulation.

Results

During the initial programme development, the first two nurses attempted cannulation in a total of 300 patients. Under direct observation, the first nurse to undertake training achieved a success rate of 84% (42 out of 50 procedures) while the second achieved 86% (43 out of 50 procedures). Where the trainee was unable to complete the procedure, this was completed using the same access route in 14 of the 15 by a consultant interventional cardiologist. In one case, transient spasm of the radial artery required access through the contralateral radial artery. There were no identified vascular complications, such as dissection, haematoma or perforation. In phase 2, nurse 1 achieved a success rate of 82% (82 out of 100 procedures), whereas nurse 2 achieved a success rate of 97% (97 out of 100 procedures). An overall success rate of 88% was achieved in the first 300 patients (table 1). During phase 2, the procedures included a mixture of both right radial and left radial access in unselected patients. Similarly, no vascular complications were identified, but one patient required alternative access due to radial spasm.

Table 1. Outcome summary of different phases of the radial access programme

| Nurse | Phase I | Phase II | Embedding practice | Total | ||||

| Success | Procedures | Success | Procedures | Success | Procedures | Success | Procedures | |

| 1 | 42 | 50 | 82 | 100 | 624 | 685 | 748 | 835 |

| 2 | 43 | 50 | 97 | 100 | 140 | 150 | ||

| 3 | 49 | 50 | 97 | 100 | 146 | 150 | ||

| 4 | 43 | 50 | 94 | 100 | 137 | 150 | ||

| 5 | 45 | 50 | 45 | 50 | ||||

| 6 | 45 | 50 | 45 | 50 | ||||

| 7 | 46 | 50 | 46 | 50 | ||||

| Total | 313 | 350 | 370 | 400 | 624 | 685 | 1,307 | 1,435 |

After completion of sign off, the nurses went on to train five other candidates within the department. Up until now, two additional nurses have successfully completed the programme and have become competent in RAA. Furthermore, another three catheter lab nurses have now completed phase 1 of the programme and are currently undergoing phase 2 training, with table 1 showing the successful outcomes of all the nursing candidates.

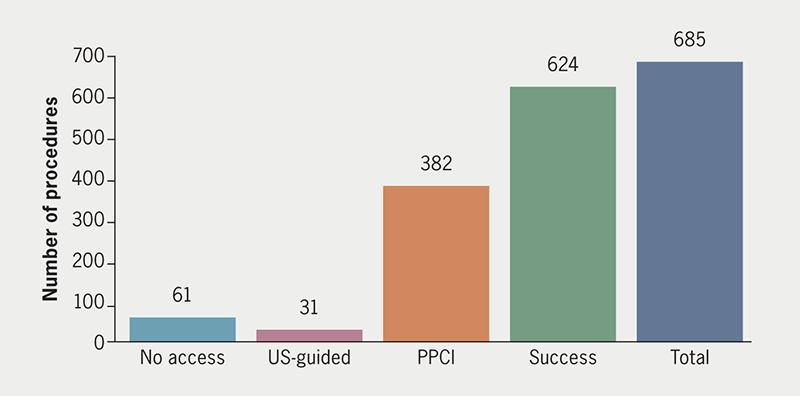

In the context of the service rollout/embedding practice, one practitioner has maintained a detailed audit of all procedures performed showing success in 624 out of 685 procedures (91.1%) completed to date (figure 1). Notably, these procedures encompassed a variety of interventions, including primary percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs) (n=382) and those guided by ultrasound (n=31). Table 1 illustrates the procedural outcomes of all the nursing participants across different phases of the radial access programme. As the table indicates, a total of 1,435 arterial catheterisation procedures have been attempted at the Royal Free Hospital during the course of the radial access programme. A significantly high success rate of 91.1% (1,307 out of 1,435 procedures) has been determined.

| Key: PPCI = primary percutaneous coronary intervention; US = ultrasound |

Comparison to medical practitioners

Medical registrars who were undergoing training in angiography, or rotating into the department, were included in the comparison. Data were collected and compared with the first two nurses undergoing the radial access programme to assess safety and efficacy.

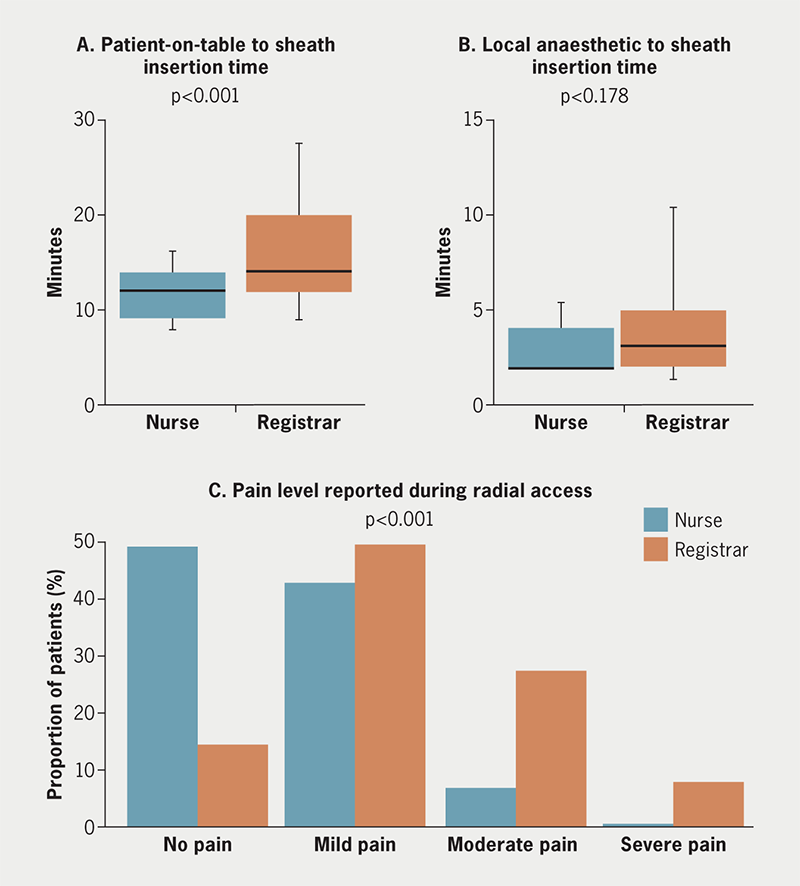

Comparing the data of 276 procedures carried out during phase 2 to a total of 138 procedures completed by the registrars; the study indicates that nurses can achieve success rates comparable with those of doctors. Patients reported less pain with nurse-led procedures (p<0.001), while time management from the point of admission to the catheter laboratory and to the completion of cannulation was noted to be efficacious (figure 2).

Time reduction

Time intervals from patient-on-table to sheath insertion were recorded for a varying number of cannulation attempts carried out by different groups of participants. The time monitoring procedure was completed for a total of 34 radial punctures undertaken by cardiology registrars and for 122 cases performed by a combination of cardiology registrars and scrub nurses. Moreover, up to 87 RAA procedures conducted by the trainee nurses were accurately timed. The average time was significantly lower at 11.56 minutes in the patient cohort of radial access nurses, as compared with the medical registrar and medical registrar plus scrub nurse at 18.02 minutes and 18.19 minutes, respectively. As indicated in figure 2, this difference was determined to be statistically significant (p<0.001).

Discussion

We have demonstrated the feasibility of introducing a nurse-led radial artery cannulation programme. The first attempt success rate was comparable with previously published success rates.20 No major arterial complications were observed during the procedure. In addition, we have demonstrated that patient experience is superior and time to cannulation is significantly reduced for the nurse-led intervention as compared with the cardiology trainees. The collective success of outcomes in those who underwent formal training, compared with those who learned using the traditional medical approach, showed that formal training resulted in a relatively lower failure rate.

Susanu et al. analysed four cardiology trainees learning to undertake radial cannulation. In the study, an experienced operator first evaluated each artery while cannulation attempts were also observed. In a total of 150 procedures, the first and second attempt success rates were 60% and 79%, respectively. The immediate complication rate was 10.7% and comprised local bleeding or haematoma formation.21 Other studies, including palpation-based radial artery cannulation with experienced operators, report first-pass success between 19% and 73%.22-24 Our audit demonstrates that at least equivalent results are possible both during training and with independent practice in a nurse-led service. It is also noteworthy that Susanu et al. found that complications were more likely when three or more arterial puncture attempts had been made during radial cannulation, thereby justifying our decision to limit attempts during training to two unsuccessful attempts.25 We, therefore, recommend that future programmes adopt a model similar to that utilised in our study.

Previous studies have focused on cannulation time from the point of administration of local anaesthesia.23 In daily practice, however, the time from a patient entering the catheter suite to access is more relevant to overall efficiency. Physicians often complete documentation from the previous procedure, or perform other duties, after a patient has been placed on the catheter table. By passing responsibility to the catheter-based nursing team, overall efficiency can be improved. We have demonstrated that nurse-led cannulation can significantly reduce the time from patient admission to the catheter laboratory to successful sheath insertion by approximately six minutes. Similarly, a training programme by Chee et al. reported a success rate of 63% in nurse-led radial artery cannulation with no adverse reactions.25 A vast majority of respondents (93%) in their study stated that they would highly recommend the training course to their colleagues.25

A standardised training programme for nurses can improve the overall patient experience, lead to significantly reduced pain perception, and can potentially reduce the incidence of radial artery spasms. The standardised operating procedures (SOPs) for the training regimen implemented by the authors have been summarised in appendix 1. The proposed model has been presented and discussed by the first author at European Society of Cardiology (ESC), British Cardiac Society (BCS) and British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS) conferences, and the SOP has been shared with hospitals such as St. Bartholomew’s, Lister, Lincoln County, Harefield, and Brompton. An overall summary of the radial access programme is shown in table 1.

A more holistic approach to patient care is achieved by training nurses in radial puncture, as post-procedural care, including maintenance of patent haemostasis, is primarily led by nurses.

Future directions

After successfully implementing the radial access training programme, future training expansion on to angiography could be considered. As outlined in appendices 1 and 2, a standardised operating policy has been established, providing other hospitals with a blueprint for implementing similar programmes.

Key messages

- There is a need to expand the literature on nurse-led radial artery access (RAA): standardised protocols need to be established and long-term outcomes of nurse-led RAA must be evaluated to understand its potential benefits better, including the potential impact of nurse-led RAA on healthcare practices and policies

- Our study highlights the potential of nurse-led RAA as a safe and efficient approach, providing valuable evidence to support its implementation in healthcare settings

- Our findings support the integration of nurse-led RAA programmes into clinical practice

Conflicts of interest

JGC has received grants, consultancy fees, and participated in speaker bureaus with Janssen Ltd., Inari and MSD. DW, RMSS, MA, TL, RR: none declared.

Funding

None.

Patient consent

In the beginning stages of our study (phases 1 and 2), patients granted consent for the nursing staff to conduct radial sheath placement. Following this, nurse-led radial cannulation became a standard practice, with all other information gathered through an audit of this routine procedure. The approval for the consenting process was granted by the new procedures committee at Royal Free Hospital, as this did not constitute a formal study that required review by the ethics board.

Study approval

The nurse-led radial access programme was authorised by the Director of Nursing following a comprehensive review of the standard operating procedures. The programme, deemed an extension of standard clinical practice rather than an investigation study, did not necessitate ethics board approval. It was designed to enhance clinical roles within established guidelines, with a focus on patient safety and care efficiency under the supervision of a cardiology consultant. Ongoing monitoring and internal evaluation ensured adherence to high standards of practice and quality assurance.

Confidentiality and anonymity of participants’ data were strictly maintained throughout the research process. The study adhered to data protection regulations, ensuring the privacy and security of participants’ personal information. The ethical considerations included participant safety, welfare, and the protection of their rights. Any potential risks were minimised, and appropriate measures were implemented to ensure the well-being of participants. The study was conducted with the utmost integrity and professionalism, ensuring the highest standards of ethical research conduct.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful for the chance to conduct this research and recognise the importance of collaboration and support throughout the study. While we cannot identify any specific individuals or organisations to acknowledge in this statement, we appreciate the contributions of all involved.

References

1. Romagnoli E, Biondi-Zoccai G, Sciahbasi A et al. Radial versus femoral randomized investigation in ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: the RIFLE-STEACS (Radial Versus Femoral Randomized Investigation in ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:2481–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2012.06.017

2. National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (NICOR). National Audit of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (NAPCI): 2020 summary report (2018/19 data). Leicester: NICOR, 2020. Available from: https://www.nicor.org.uk/national-cardiac-audit-programme/previous-reports/pci-1/2021-5/national-audit-of-percutaneous-coronary-intervention-2020-summary-report-final?layout=default

3. Tröbs M, Achenbach S, Plank PM et al. Predictors of technical failure in transradial coronary angiography and intervention. Am J Cardiol 2017;120:1508–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.07.049

4. Merkle J, Hohmann C, Sabashnikov A, Wahlers T, Wippermann J. Central vascular complications following elective catheterization using transradial percutaneous coronary intervention. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep 2017;5:2324709617698717. https://doi.org/10.1177/2324709617698717

5. Basu D, Singh PM, Tiwari A, Goudra B. Meta-analysis comparing radial versus femoral approach in patients 75 years and older undergoing percutaneous coronary procedures. Indian Heart J 2017;69:580–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ihj.2017.02.003

6. Mamas MA, Tosh J, Hulme W et al. Health economic analysis of access site practice in England during changes in practice: insights from the British Cardiovascular Interventional Society. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2018;11:e004482. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.004482

7. Cereda A, Allievi L, Busetti L et al. Nurse-led distal radial access: efficacy, learning curve, and perspectives of an increasingly popular access. Minerva Cardiol Angiol 2023;71:35–43. https://doi.org/10.23736/S2724-5683.22.05843-4

8. Gill FJ, Kendrick T, Davies H, Greenwood M. A two phase study to revise the Australian Practice Standards for Specialist Critical Care Nurses. Aust Crit Care 2017;30:173–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2016.06.001

9. Jamshidi R. Central venous catheters: indications, techniques, and complications. Semin Pediatr Surg 2019;28:26–32. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2019.01.005

10. Zhang Z, Brusasco C, Anile A et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of central venous catheter for critically ill patients. J Emerg Crit Care Med 2018;2:5. https://doi.org/10.21037/jeccm.2018.05.05

11. Crocoli A, Cesaro S, Cellini M et al. In defense of the use of peripherally inserted central catheters in pediatric patients. J Vasc Access 2021;22:333–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1129729820936411

12. Crowley JJ. Vascular access. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol 2003;6:176–81. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.tvir.2003.10.005

13. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Cost saving and resource planning. London: NICE, 2022. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/cost-savings-resource-planning

14. Leigh J, Roberts D. Critical exploration of the new NMC standards of proficiency for registered nurses. Br J Nurs 2018;27:1068–72. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2018.27.18.1068

15. Sosnowski K, Dobbyn D. A nurse initiated arterial line insertion service: the implementation of a pilot program is supported by nursing and medical staff. Aust Crit Care 2011;24:75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2010.12.058

16. Chee BC, Baldwin IC, Shahwan-Akl L, Fealy NG, Heland MJ, Rogan JJ. Evaluation of a radial artery cannulation training program for intensive care nurses: a descriptive, explorative study. Aust Crit Care 2011;24:117–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2010.12.003

17. Casanova-Vivas S, Micó-Esparza JL, García-Abad I et al. Training, management, and quality of nursing care of vascular access in adult patients: the INCATIV project. J Vasc Access 2023;24:948–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/11297298211059322

18. Williams T, Condon J, Davies A et al. Nursing-led ultrasound to aid in trans-radial access in cardiac catheterisation: a feasibility study. J Res Nurs 2020;25:159–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987119900374

19. Gronbeck C 3rd, Miller EL. Nonphysician placement of arterial catheters. Experience with 500 insertions. Chest 1993;104:1716–17. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.104.6.1716

20. Tangwiwat S, Pankla W, Rushatamukayanunt P, Waitayawinyu P, Soontrakom T, Jirakulsawat A. Comparing the success rate of radial artery cannulation under ultrasound guidance and palpation technique in adults. J Med Assoc Thai 2016;99:505–10. Available from: https://www.thaiscience.info/journals/Article/JMAT/10983045.pdf

21. Susanu S, Angelillis M, Giannini C et al. Radial access for percutaneous coronary procedure: relationship between operator expertise and complications. Clin Exp Emerg Med 2018;5:95–9. https://doi.org/10.15441/ceem.17.210

22. Genre Grandpierre R, Bobbia X, Muller L et al. Ultrasound guidance in difficult radial artery puncture for blood gas analysis: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2019;14:e0213683. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213683

23. Yu Y, Lu X, Fang W, Liu X, Lu Y. Ultrasound-guided artery cannulation technique versus palpation technique in adult patients in pre-anesthesia room: a randomized controlled trial. Med Sci Monit 2019;25:7306–11. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.916252

24. Pancholy SB, Sanghvi KA, Patel TM. Radial artery access technique evaluation trial: randomized comparison of Seldinger versus modified Seldinger technique for arterial access for transradial catheterization. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2012;80:288–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccd.23445

25. Chee BC, Baldwin IC, Shahwan-Akl L, Fealy NG, Heland MJ, Rogan JJ. Evaluation of a radial artery cannulation training program for intensive care nurses: a descriptive, explorative study. Aust Crit Care 2011;24:117–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2010.12.003