HEART UK – The Cholesterol Charity held its 25th annual conference at Warwick University from 6th-8th July 2011, entitled ‘Partners in Prevention – Lipids in Cardiovascular Disease and Beyond’. The conference looked at past, present and future strategies for assessing and reducing risk of cardiovascular disease. Highlights included news of the upcoming Joint British Societies guidelines update, and the launch of a new campaign to map variations in coronary heart disease mortality across England. Tim Kelleher reports.

Heart hotspots campaign

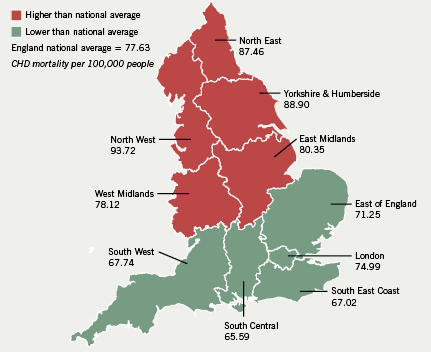

The North/South divide in coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality remains significant despite improvements in cardiovascular disease (CVD) care, according to the ‘Heart Hotspots’ campaign launched at this year’s conference.

The North West region has the highest mortality (93.72 per 100,000) versus South Central, which showed the lowest mortality (65.59 people per 100,000), according to NHS Information Centre data highlighted by the campaign (figure 1).1 CHD mortality in Tameside and Glossop, near Manchester, is almost four times as high as for those living in Kensington and Chelsea, London (140.84 vs. 36.91 people per 100,000), it found.

Wide variations were also seen within Southern cities. In London, for example, a person in Islington is three times more likely to die of CHD (114.12 people per 100,000) than someone in Kensington and Chelsea (36.91 people per 100,000), and more than twice as likely to die compared to those in Westminster (46.76 people per 100,000). These data reflect recent findings from the Care Quality Commission.2

As part of the campaign, a survey sponsored by Merck Sharp & Dohme Ltd. (MSD) shows that prevention of CVD is not a current priority for some people despite them already having risk factors. Some 1,034 people were questioned by ICM Research during June across England, Scotland and Wales. More than two thirds (69%) were not worried about their cardiovascular health, even though 19% had high blood pressure, 14% had high cholesterol and 5% already had a heart condition. While 66% of people were likely to start exercising, improve their diet or lose weight to make themselves more physically attractive, only 36% started exercising to reduce the risk of damaging their heart.

Professor Sir Roger Boyle, National Director for Heart Disease and Stroke, commented: “The latest data reinforce the fact that despite recent progress in the management of CVD, there is still more that we can do to ensure people are aware of the risk factors for having a heart attack or stroke and what can be done to address these risk factors. The ‘Heart Hotspots’ campaign is a valuable step in raising awareness and it is vital that we continue to focus on tackling the UK’s leading cause of death, CVD, and ensuring that inequalities are being addressed”.

The campaign will help primary care trusts (PCTs) to monitor local healthcare performance, enabling better targeting of resources, HEART UK claims. Plans to contact MPs, particularly those from problem areas, will also help to spread local awareness of the campaign and its initiatives, it is hoped.

JBS3 guidelines

The updated Joint British Societies guidelines on the prevention of CVD (JBS3) are due to be published in October/November this year, and will greatly benefit from upgrading to lifetime risk measures, said Dr Alan Rees (University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff).

The new guidelines are to include an even broader coalition of specialist societies, and recognise the inherent cardiovascular risk in patients with chronic kidney disease, peripheral vascular disease, and a reappraisal of the differing risks in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Although their final details are yet to be agreed, the guidelines will focus on active management of high-risk patients, and the adoption of an innovative means of calculating CVD risk, Dr Rees said. Guidelines based on the established 10-year risk metric are inadequate, he claimed, highlighting the fact that a person can have both a low 10-year risk and a high lifetime risk of CVD. Dependence on short-term measures discourages early intervention and delays treatment, which could impair CVD prevention, he said.

The JBS3 guidelines will use an updated lifetime risk measure, using factors including heart age and time until first cardiovascular event to calculate how many heart attack or stroke free years a patient has remaining. ‘Heart age’, Dr Rees clarified, will be a graphic new means of communicating CVD risk to patients, impressing on them that in terms of cardiac health “after a certain time chronological age becomes irrelevant”.

There is some dispute amongst JBS3 authors as to whether the Framingham or QRISK algorithms should be used to calculate risk, debate hinging on social deprivation as a risk factor for CVD, Dr Rees revealed. While the inclusion of deprivation by QRISK was described by some as “crude”, it was considered by others as preferable to no inclusion at all, he said.

Myant lecture

This year’s guest Myant lecturer, Professor Ernst J Schaefer (Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, USA), also spoke on cardiovascular risk factors for the 21st century, assessing the various risk factors incorporated by competing scores used to calculate CHD risk. He cast the Framingham risk score as an inferior tool to newer algorithms, such as the Reynolds risk score, which incorporates family history and increased C reactive protein (CRP), and the PROCAM score which factors in both family history and triglycerides (but does not incorporate CRP).

Professor Schaefer also briefly summarised key developments in lipid research, from the work of 19th century pathologist Rudolf Virchow to that of his own mentor Dr Robert I Levy. He spoke at length on the atherogenic activities of the lipoprotein (Lp(a)) particle, as well as the protective properties of apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA-1).

Physical activity and CVD prevention

Traditional guidelines on physical activity are outdated and overly simplistic, according to research presented by Dr Jason Gill (Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences, University of Glasgow). He surveyed the body of evidence on reducing CVD risk with physical activity, as well as the increased risk associated with a sedentary lifestyle.

He asserted that the benefits of physical activity go beyond simple reduction of fat, resulting from its effects on lipid metabolism, insulin sensitivity, blood pressure and inflammation. It is important to communicate to the public that exercise without weight loss can considerably reduce visceral and ectopic fat deposits, he said, asserting that weight and waist circumference are not necessarily the best measures of exercise’s health impact.

He acknowledged that lifestyle changes are a “difficult public health issue”, with exercise guidelines caught in a “tug of war between what people are prepared to do and the optimal amount”. However, we should move on from the traditional recommendation of 30 minutes of exercise at least five days a week, he claimed.

Recent research he cited recommends more targeted goals of 150 minutes moderate or 75 minutes of vigorous exercise per week for beginners, and 300 minutes moderate or 150 minutes vigorous per week for conditioned individuals.3

He also drew attention to the newly published guidelines on physical activity from the DOH, which are the first UK guidelines to cover sedentary lifestyle as an independent risk factor for ill health.4

CVD and possible use

of the polypill

Use of a polypill is a potentially powerful tool in the prevention of CVD in those most at risk, said Dr Tom Marshall (University of Birmingham). He argued that, despite their differences, major algorithms for cardiovascular risk such as Framingham, QRISK, ASSIGN and SCORE, all show age and gender to be stronger predictors than individual risk factors.

Overemphasis on normalising individual risk factors could distract from the goal of preventing CVD in those at highest risk, he claimed, citing the proven benefits of antihypertensives, statins and aspirin as a more reliable means of prevention. Multiple therapy combining such medication is the logical course of treatment for high risk patients, he said.

Future plans

HEART UK Chief Executive Jules Payne laid out the charity’s plans for the coming years, including this year’s National Cholesterol Week ‘Know It, Lower It!’ from the 19th–25th September 2011. It will focus this year on improving public awareness of cholesterol levels as a CVD risk factor, and how to maintain them – HEART UK’s objective is that by 2016 a majority of British adults will know their cholesterol levels, and the best methods of improving them, she announced.

Other inititatives include ‘Health Unlocked’, a free online community for those suffering from or concerned about high cholesterol to share questions and experiences,5 and ‘Medicine & Me: Living with Cholesterol’,6 a CPD accredited meeting between patients, families, and medical experts to be held at the Royal Society of Medicine, 26th October 2011.

Further information

- NHS Information Centre For Health and social care. Mortality from coronary heart disease 1993–2009. 2011. Available from: http://www.nchod.nhs.uk

- www.cqc.org.uk/_db/_documents/Closing_the_gap.pdf

- O’Donovan G, Blazevich AJ, Boreham C, et al. The ABC of Physical Activity for Health: A consensus statement from the British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences. J Sport Sci 2010;28:573–91.

- http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_127931

- http://heartuk.healthunlocked.com

- www.rsm.ac.uk/medandme