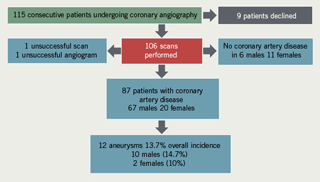

Within a prospective observational study we investigated whether patients undergoing coronary angiograms present a more accessible and significant cohort for abodominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) screening. With local research ethics committee approval, over 36 days, 106 consecutive patients consented to and underwent a five to eight minute aortic scan, using a portable ultrasound unit, during the recovery period after angiography. Anteroposterior and transverse, suprarenal and maximal infrarenal aortic diameters were measured. The ultrasonographer was blinded to the angiogram results.

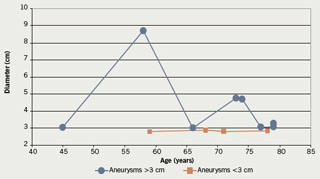

Of 104/106 successful scans 73 were conducted in male patients and 31 in female patients. Six males and 11 females had normal coronary arteries and no aneurysms. From 87 patients with ischaemic heart disease (IHD), eight males had aneurysms ≥3 cm diameter. Mean diameter was 4.2 cm (standard deviation [SD] 1.96, range 3–8.7 cm). Two additional males and two females had focal aortic dilatations of twice suprarenal aortic diameter yielding 14.9% and 10% incidence of aneurysmal change in scanned males and females with IHD. Average ages for patients with IHD were 62.2 years (SD 10.7, range 41–81 years) for males and 68.0 years (SD 10.6, range 47–88 years) for females. Average age for males with aneurysmal change was 68.8 years (SD 11.5, range 45–79 years).

Results from this pilot study suggest that screening patients with IHD has a significantly higher yield than expected by the National Programme. These high-risk patients would benefit more than the general population from early detection and cardiovascular optimisation possibly with earlier AAA repair. Further expansion of the study would allow corroboration and qualification of these findings.

Introduction

The UK government’s recent commitment to aneurysm screening and the potential for funding this, will undoubtedly lead to increased interest in the organisation of new screening programmes by different trusts. In April 2007, the UK National Screening committee – AAA Screening Working Group published a draft for Standard Operating Procedures For An Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA) Screening Programme.1 The recommendations for population selection offer a single scan for males in the year they reach 65 years of age and also for males over 65 on request. Females, males under 65, those receiving previous AAA surgery, patients with terminal illness or other severe health problems are excluded, as well as individuals who specifically request not to be screened. Selection by other risk factors including a strong family history was mentioned, however, it was not anticipated that these patients would be incorporated into the National Screening Programme.

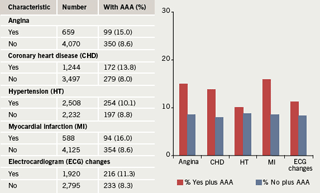

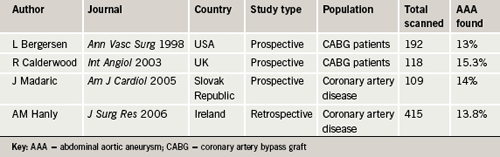

Ischaemic heart disease (IHD) has long been associated with AAA as a factor increasing co-morbidity and mortality in the management of AAA,2,3 however, the converse relationship has not been given much weight. In 1996 the Cardiovascular Health Study published some results that suggested a higher prevalence of AAA existed in patients with cardiovascular disease (figure 1).4 There has been some enthusiasm for screening the abdominal aorta during transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) and published papers have yielded prevalences of AAA of 0.82%,5 3%,6 3.8%7 and 5.7%,8 when looking at all TTE referrals. One paper examining a population referred for TTE during the investigation of hypertension yielded a prevalence of 6.5%.9 Another passing trend was to include abdominal aortic views during coronary angiography, and published papers yielded prevalences of AAA of 4.9%,10 8%11 and 8.9%.12 Three publications examining the incidence of AAA in patients with IHD in the USA, UK, the Slovak Republic and Ireland found prevalences of 13%,13 15.3%,14 14%15 and 13.8%16 (table 1), suggesting a higher prevalence of AAA in patients with IHD than that in the general population of males over 65 years, where the expected prevalence is 5–10% (Multi-centre Aneurysm Screening Study [MASS] 4.9%,17 Chichester 7.7%18).

Patients with IHD and AAA present a high-risk population and a bigger challenge for management. It would be ideal to identify these patients earlier in the course of their cardiovascular disease process when they present for their first angiogram soon after the onset of their first cardiovascular symptoms. Additionally, scanning this cohort of patients promises a higher yield of AAA than scanning the general population of males over 65 years. In the absence of any similar UK studies, this paper investigates the prevalence of AAA within a population of patients found to have coronary heart disease diagnosed by angiography in a district general hospital, and highlights the facility of carrying this out during the recovery period immediately after angiography.

Methods

The ideal population for this study in Broomfield Hospital, Chelmsford, UK, was identified. This constituted patients in the recovery period just after coronary angiography. According to coronary unit protocol, these patients, who have been starved for the procedure, are kept supine in private cubicles for 45 minutes after angiography. This presents an ideal window for ultrasonography of the abdominal aorta.

The study proposal was submitted to and endorsed by the North and Mid Essex NHS Research Ethics Committee (06/Q0303/12, R&D 494). Funding from the Mid Essex Hospital Trust (MEHT) Research and Development (R&D) Support Fund was granted for the purchase of a Sono Site® MicroMaxx® portable system for the study.

Participants were given a four-page information booklet during pre-clerking and further explanation was offered by the ultrasonographer prior to the procedure before participants signed consent forms included in the booklet. This facilitated the collection of basic data including patient name, sex and date of birth just before ultrasound.

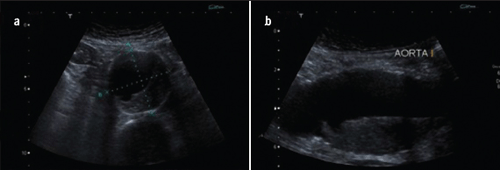

Aortic scans were performed as follows: a Sono Site® MicroMaxx® portable system and a curvilinear probe (C60e/5–2 MHz) were used. The aorta was identified in longitudinal section just above its bifurcation and then followed up into the epigastrium where the renal arteries were identified. The immediately suprarenal aorta was measured in transverse and longitudinal (anteroposterior) section and similar measurements were then obtained at the maximum diameter of the infrarenal aorta. Average time for scanning was approximately six minutes.

Angiography results were recorded after the scans were performed and further patient data were collected from Integrated Care Pathway booklets filled in by trained coronary unit nurses during pre-clerking. Data included mode of presentation, associated co-morbidity, medications, past medical and smoking history, serum creatinine and haemoglobin levels, height and weight. Data were entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and processed.

Results

A total of 115 patients were approached to participate in this preliminary study. After reading the booklets and any necessary further explanations, nine patients declined to participate, while 106 patients gave written consent and were scanned. One scan was unsuccessful because of a combination of patient girth and obscuring bowel gas. One angiogram was also unsuccessful so the data for this patient were not included.

The mean age of the patients scanned was 63.7 years (standard deviation [SD] 10.82), median 63 years (range 40–88 years). There were 31 females and 73 males.

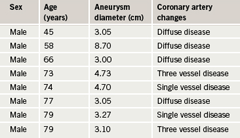

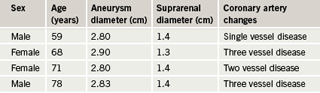

Angiogram results revealed that six males and 11 females had no coronary artery disease. Of the remaining 87 patients, eighteen males and 11 females had diffuse/non-obstructive coronary artery disease, 28 males and two females had single vessel disease, 11 males and four females had two vessel disease and 10 males and three females had three vessel disease. All the patients with aneurysms had coronary

artery changes.

Aneurysmal change was found in 12 patients: 10 males and two females. This means that 13.7% of the patients with IHD had aneurysms: 14.9% of males and 10% of females. Mean age for males with aneurysms was 68.8 years (SD 11.5), median 73.5, range 45–79 years. The two females with aneurysms were 68 and 71 years old. The findings are depicted in

tables 2 and 3 and figures 2 and 3.

Discussion

This study was intended as a pilot series to help elucidate the value of scanning the population of patients with IHD. Its small numbers do not give sufficient power to the findings to sway national policy, however, it has shown that this population is worth further study. Further collected data, such as the incidence of co-morbidity, medications, body mass index (BMI), etc., also were not analysed for this reason. Scanning and data collection at Broomfield Hospital continues.

In keeping with the findings from the papers already quoted,4,13-16 this study found an overall prevalence of 13.7% of IHD patients who had aneurysmal change: 14.9% of males and 10% of females. Aneurysms have been defined through various measurements. The commonest applied definition is that of a diameter of 3 cm. The definition of a focal increase in diameter to twice that at the renal arteries is probably more appropriate. An ectatic aorta could be greater than 3 cm with a much lower risk of aneurysmal progression to rupture than focal aneurysmal change.19 The question of the significance of 3 cm aneurysms in patients over the age of 75 may arise. Again we stress the lack of power of this study, however, the age of patients being operated on for AAA both electively and as emergency treatment of ruptures is creeping up slowly to beyond 80–85 years, and this might in the future change the perspective on patient age. Currently, up to 20% of open aneurysm surgery in UK district general hospitals is carried out in patients over 80 years old (R Abela unpublished data).

The high incidence of coronary artery disease in patients with AAA has always been a main concern in their peri-operative management and post-operative survival. Incidence of coronary artery disease in up to 63% in AAA patients has been reported20 and myocardial infarction is the cause of up to 61% of early post-operative deaths in elective open AAA repair.21 This justifies the need for some degree of cardiac work-up in all pre-operative aneurysm patients, as well as cardiac optimisation by medication or revascularisation in a significant proportion. Current expected standards in healthcare delivery no longer exclude patients with IHD from surgical procedures. On the contrary, the responsibility now lies in optimising these patients to make them similarly safe candidates for surgery as patients without IHD. Screening patients for AAA early in the course of their IHD, as soon as coronary diagnostic procedures are initiated, at their first coronary angiogram would facilitate diagnosis at an early stage before their cardiac function deteriorates irretrievably.

Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) is now also sufficiently widely established to offer IHD patients aneurysm repair minus the risks of general anaesthetic and cross-clamping. It is associated with a lower incidence of peri-operative cardiac arrhythmias, myocardial ischaemia, troponin T release, cardiac events, and all-cause mortality compared with open AAA repair.22 The issue of suitability of an aneurysm for endovascular repair arises therein, however, though there is no evidence whether smaller aneurysms might present more suitable anatomy for endovascular intervention, small aneurysms (4–5.4 cm diameter) have been found to have better results and long-term outcomes.23,24

One major issue in carrying out screening is the availability of trained personnel to carry this out. Though ultrasonographic measurement and follow-up of AAA is routinely carried out by dedicated ultrasonographers, vascular technicians and radiologists, implementation of screening all patients undergoing angiography for IHD in a busy coronary angiography unit by these personnel would not be a practical arrangement. Identification of the aorta by ultrasound scanning and measurement of diameters with user-friendly portable scanners should be within the realm of basic training (figure 4). A recent article from the University of Western Ontario studied the feasibility of a nurse-supervised aneurysm screening programme.25 Specialist nurses are being established as key participants in surgical, laparascopic and endoscopic fields. Coronary angiography units in the UK are tightly and efficiently run by dedicated nursing staff. Motivated individuals among these nurses could be trained, not only to run a screening service within their unit, but also to carry out the screening and basic aortic diameter measurements as a primary screening front. Patients with significant findings could be referred to the hospitals’ vascular units for confirmation of findings.

In conclusion, this study strongly suggests that patients with IHD constitute a population at higher risk of developing significant AAA. Early screening in conjunction with the onset of their initial diagnostic work-up for coronary artery disease could significantly alter their management and outcomes. A larger prospective study is warranted to establish whether a history of IHD should become an inclusion criterion into current aortic aneurysm screening programmes within a sub-category for high-risk patients.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by MEHT R5D Support Fund 2006/7.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Key messages

- Patients with ischaemic heart disease have a higher incidence of abdominal aortic aneurysm

- The post-angiography recovery period presents an ideal window for screening high-risk patients

References

- AAA Screening Working Group. Standard operating procedures for an Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA) screening programme. UK National Screening Committee, 2007.

- Newman A, Arnold A, Burke G et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysms detected by ultrasonography: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:182–90.

- Jamieson WR, Janucz MT, Miyagishima RT et al. Influence of ischaemic heart disease on early and late mortality after surgery for peripheral occlusive vascular disease. Circulation 1982;66(2 Pt 2):192–7.

- Hope G, Wolfson S, Sutton-Tyrrell K et al. Risk factors for abdominal aneurysms in older adults enrolled in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1996;16:963.

- Seelig MH, Malouf YL, Klinger PJ et al. Clinical utility of routine screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm during echocardiography. VASA 2000;29:265–8.

- Eisenberg MJ, Geraci SJ, Schiller NB. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms during transthoracic echocardiography. Am Heart J 1995;130:109–15.

- Giaconi S, Lattanzi F, Orsini E et al. Feasibility and accuracy of a rapid evaluation of the abdominal aorta during routine transthoracic echocardiography. Ital Heart J 2003;4(4 Suppl):332–6.

- Janussi A, Fontana P, Mueller XM. Imaging of the abdominal aorta during examination of patients referred for transthoracic echocardiography. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1999;129:71–6.

- Spittell PC, Ehrsam JE, Anderson L et al. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm during transthoracic echocardiography in a hypertensive population. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1997;10:722–7.

- Fusari M, Parolari A, Agostinelli A et al. Coronary and major vascular disease: aggressive screening and priority-based therapy. Cardiovasc Surg 2000;8:22–30.

- Benzaquen BS, Garzon P, Eisenberg MJ. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm during cardiac catheterization. J Invasive Cardiol 2001;13:100–06.

- Rigatelli G, Roncon L, Bedendo E et al. Concomitant vascular and coronary artery disease: a new dimension for the global endovascular specialist? Clin Cardiol 2005;28:231–5.

- Bergersen L, Kiernan MS, McFarlane G et al. Prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysms in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass. Ann Vasc Surg 1998;12:101–05.

- Calderwood R, Welch M. Screening men for aortic aneurysm. Int Angiol 2004;23:185–8.

- Madaric J, Vulev I, Bartunek J et al. Frequency of abdominal aortic aneurysm in patients >60 years of age with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 2005;96:1214–16.

- Hanly AM, Javad S, Anderson LP et al. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms in cardiovascular patients. J Surg Res 2006;132:52–5.

- Kim LG, Scott AP, Ashton HA, Thompson SG. A sustained mortality benefit from screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:699–706.

- Ashton HA, Gao L, Kim LG, Druce PS, Thompson SG, Scott RAP. Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomised clinical trial of ultrasonic screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br J Surg 2007;94:696–701.

- Basnyat PS, Aiono S, Warsi AA et al. Natural history of the ectatic aorta. Cardiovasc Surg 2003;11:273–6.

- Ferro CR, de Oliveria DC, de Freitas Guimaraes Guerra F et al. Prevalence and risk factors for combined coronary artery disease and aortic aneurysm. Arq Bras Cardiol 2007;88:40–4.

- Diehl JT, Cali RF, Hertzer NR et al. Complications of abdominal aortic reconstruction. Ann Surg 1983;197:49–56.

- Feringa HH, Karagiannis S, Vidakovic R et al. Comparison of the incidence of cardiac arrhythmias, myocardial ischaemia and cardiac events in patients treated with endovascular versus open surgical repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Am J Cardiol 2007;100:1479–84.

- Zarins CK, Crabtree T, Bloch DA et al. Endovascular aneurysm repair at 5 years: Does aneurysm diameter predict outcome? J Vasc Surg 2006;44:920–9.

- Peppelenbosch N, Buth J, Harris PL et al. Diameter of abdominal aortic aneurysm and outcome of endovascular aneurysm repair: does size matter? A report from EUROSTAR. J Vasc Surg 2004;39:288–97.

- Lovell MB, Harris KA, DeRose G et al. A screening program to identify risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysms. Can J Surg 2006;49:113–16.