Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia and is a major risk factor for stroke. The 2006 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines on management of AF recommended the use of beta blockers and calcium channel blockers in preference to digoxin for first-line rate control and emphasised the importance of appropriate thromboprophylaxis.

We audited management of AF at the Royal Surrey County Hospital against standards derived from the NICE guidelines. Fifty-nine of the 663 patients (8.9%) presenting to the acute medical take during the month of May 2008 had a documented diagnosis of AF, 10% of whom presented with a new diagnosis of AF and 90% of whom had a pre-existing diagnosis. The case notes of these 59 patients were reviewed.

All patients with a new diagnosis of AF were managed consistently with the NICE guidelines. Compliance for patients with pre-existing AF was much lower. Eighteen out of 31 patients (58%) with pre-existing AF were found to be on digoxin monotherapy on admission. Inadequate thromboprophylaxis on admission was found in 51% of all patients with pre-existing AF.

These results indicate compliance with NICE guidelines can be improved and a need for raised awareness in the community, particularly with regard to risk stratification for thromboprophylaxis.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia with a reported prevalence of 0.4–1% in the general population, increasing with age to afflict 9% of the population aged 80 years and over.1 It represents a significant risk factor for stroke if left untreated.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines for management of AF were issued in June 2006 and placed particular importance on the use of beta blockers and non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers as first-line rate control agents in preference to digoxin.2 Digoxin is as effective as beta blockers and calcium channel blockers in controlling heart rate during normal daily activities, but is less effective than these agents at high levels of physical exertion.3

The guidelines also emphasised the importance of assessment for, and initiation of, thromboprophylaxis with correct risk stratification. AF is an independent risk factor for stroke and the benefits of thromboprophylaxis in AF patients are well established.4,5 For both primary and secondary prevention, warfarin is more effective than aspirin in reducing risk of stroke,6,7 though it may be associated with increased risk of bleeding, and in a Cochrane review comparing warfarin and aspirin for primary prevention in patients with non-rheumatic AF, all-cause mortality was similar for the two groups.6

Patients with paroxysmal AF are at the same risk of thromboembolic events as patients with persistent AF and, hence, risk stratification should be conducted according to the same criteria and not guided by the frequency or duration of paroxysms.8

We performed an audit regarding two important aspects of the management of patients with AF presenting to the acute medical take at the Royal Surrey County Hospital against standards derived from the NICE guidelines.2 They were:

- All patients who are prescribed digoxin as initial monotherapy for rate-control are to have the reason for this prescription recorded where it is not obvious (for example, a sedentary lifestyle or presence of contraindications to alternative agents).

- All patients should be assessed for risk of stroke/thromboembolism and given thromboprophylaxis according to the NICE stroke risk stratification algorithm,2 which classifies patients into low, moderate and high thromboembolic risk groups. Low-risk patients are <65 years with no risk factors. High-risk patients are those with a history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA), or those >75 years with hypertension, diabetes mellitus or vascular disease, or those with heart failure or valve disease. Aspirin is recommended for low-risk patients and warfarin for high-risk patients. Moderate risk patients are those who are >65 years with no risk factors, or those who are <75 years with hypertension, diabetes or vascular disease. Either aspirin or warfarin is recommended for thromboprophylaxis in this group and treatment can be decided on an individual basis.

Methods

All patients presenting to the acute medical take under the care of all physicians during the month of May 2008 were screened for a documented diagnosis of AF. Patients with a documented diagnosis of paroxysmal AF but who were in sinus rhythm on admission were included in the AF cohort. Patients with atrial flutter were excluded. Case notes and discharge summaries for the AF patients were reviewed post-discharge to collate information using a standardised proforma.

Results

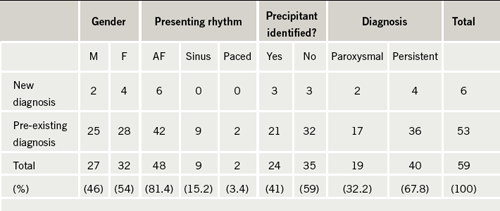

Six hundred and sixty-three patients presented to the acute medical take in the month of May 2008, 59 of whom were identified as having a primary or an additional diagnosis of AF, equating to 8.9%, which is consistent with the reported prevalence of AF.1 The demographics of these patients are shown in table 1. Fifty-three patients (90%) had a pre-existing diagnosis, while just six (10%) had a new diagnosis made during admission. The mean age was 80 years (range 31–95 years). Forty of the patients (67.8%) had persistent or permanent AF and 19 (32.2%) had paroxysmal AF. A precipitant for AF was identified in 24 patients (41%); the precipitant in the vast majority of these patients was chest infection.

Standard 1: All patients who are prescribed digoxin as initial monotherapy for rate-control are to have the reason for this prescription recorded

Three of the patients with new AF were started on a rate-control strategy (two with a beta blocker and one with a beta blocker plus digoxin). One patient with new AF was started on a rate plus rhythm control strategy with a calcium channel blocker and intended elective direct current cardioversion. Compliance was therefore 100% with this standard for patients with new AF.

There were 31 patients with pre-existing AF. Digoxin monotherapy was deemed ‘appropriate’ where there was documentation of contraindications to beta blockers and calcium channel blockers, or documentation of a sedentary lifestyle. In the absence of both these criteria, or where the patient was found to have paroxysmal as opposed to persistent or permanent AF, digoxin monotherapy was deemed ‘inappropriate’. Eighteen of these patients (58%) were found to be on digoxin monotherapy on admission and according to the above criteria, this was ‘appropriate’ in just nine patients. Digoxin monotherapy was found to be ‘inappropriate’ in the other nine patients: six of them were not sedentary and had no contraindications to beta blockers and calcium channel blockers, and the other three patients had a diagnosis of paroxysmal AF and were in sinus rhythm on admission.

We also found four patients with paroxysmal AF who had progressed to permanent AF and who were started on rate control during admission having previously been on rhythm control only or no treatment. Two of these patients were started on a beta blocker and two on digoxin monotherapy, one appropriately (a sedentary patient) but another inappropriately (not sedentary and no contraindications to beta blockers or calcium channel blockers).

Standard 2: All patients should be assessed for risk of stroke/thromboembolism and given thromboprophylaxis according to the stroke risk stratification algorithm

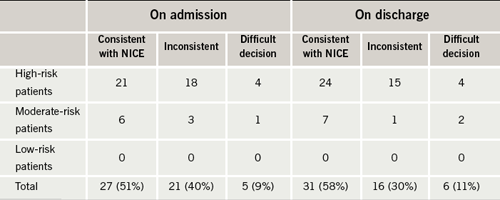

Each patient’s case notes were reviewed carefully to establish whether or not thromboprophylaxis was consistent with the NICE stroke risk stratification algorithm.2 In a minority of cases (9%) it was not clear cut whether or not thromboprophylaxis was appropriate; this was usually in patients at increased risk of harm from warfarin or aspirin but where these risks could potentially be outweighed by the benefits (such as in patients at high risk of thromboembolism with previous but not active peptic ulceration). These patients were classified as being ‘difficult clinical decisions’.

All of the patients with a new diagnosis of AF were started on thromboprophylaxis that was consistent with the algorithm. Five of the six patients were classified as ‘high risk’: three were started on warfarin; two were started on aspirin due to contraindications to warfarin; and one was started on aspirin but with a view to delayed consideration of warfarin as they had presented with a new stroke. One patient was classified as ‘moderate risk’ and he was started on aspirin appropriately.

Compliance with this standard was lower for the patients with pre-existing AF. The majority of these patients were also stratified as ‘high risk’ (81%) with the remainder classified as ‘moderate risk’ (19%) and none as ‘low risk’. As shown in table 2, on admission, only 27 patients (51%) were being managed consistent with the NICE stroke risk algorithm, while 21 (40%) were not. Five patients (9%) fell into the ‘difficult decision’ category. These figures improved on discharge indicating that some of the patients were having their risk re-assessed and medication changed appropriately, but they still fell short of the standard with just 31 patients (58%) managed consistently with the algorithm on discharge.

Discussion

We performed a detailed case note review of 59 patients with AF presenting to the acute medical take of a district general hospital over a month-long period and evaluated management of their AF against standards derived from the NICE guidelines. The majority of these patients (90%) had a pre-existing diagnosis of AF.

For patients with a new diagnosis of AF, compliance with Standard 1 was good: none were discharged on digoxin monotherapy. Likewise, regarding Standard 2, all patients were given thromboprophylaxis consistent with the NICE stroke risk algorithm. An obvious limitation of the results for this group of patients is the small size of the cohort; our results imply, however, that practice is generally consistent with the NICE guidelines.

For patients with pre-existing AF, analysis of this larger group of 53 patients indicated that management of AF in the community has poor compliance with NICE guidelines. Regarding Standard 1, 18 of the patients admitted were found to be on digoxin monotherapy in the community. In nine of these patients (50%) digoxin monotherapy was ‘inappropriate’ as there were no documented contraindications to beta blockers and calcium channel blockers and they did not have a sedentary lifestyle, or they had paroxysmal AF. It was not always apparent whether digoxin had been started in primary or secondary care and it is important to consider that there may well be other reasons not documented as to why some of these patients were on digoxin (for example, they might have been tried on a beta blocker in the community but changed to digoxin due to poor tolerance of the side effects – this information would not necessarily be found in the hospital notes). Furthermore, most patients with AF have traditionally been treated with digoxin as first-line treatment in the past and our finding reflects this practice.

Only two of the nine patients with no obvious reason for digoxin monotherapy had their medication reviewed and changed during admission to treatment compliant with the NICE guidelines while the remaining seven were continued on digoxin. There are many reasons why an acute hospital admission may not be an appropriate juncture at which to change management: the patient may have been stable on digoxin for years; digoxin may have been chosen over an alternative rate-control agent for reasons not apparent in the hospital notes; and the patient may have presented a problem entirely unrelated to their AF. Further evaluation of heart rate control may be necessary in some patients before a blanket change from digoxin to a beta blocker or calcium channel blocker. However, an acute admission could be effectively utilised as an opportunity to review medication and either amend management or make recommendations for primary care on the discharge letter. There is no guidance from NICE as to whether digoxin should be replaced in patients already receiving this medication.

Compliance with Standard 2 was also poor. Of the 53 patients with pre-existing AF, just 27 (51%) were on appropriate thromboprophylaxis. There was some improvement in the number of patients on appropriate thromboprophylaxis on discharge (31 patients) indicating that some clinicians were re-assessing risk during admission and modifying thromboprophylaxis appropriately, but the number is still too low. Of particular concern were two patients admitted and discharged without any thromboprophylaxis despite an absence of contraindications to aspirin or warfarin.

There is often a reluctance to use warfarin for fear of bleeding complications and the reasons for not starting thromboprophylaxis may be based on a clinician’s judgement. Important subjective considerations impacting on the clinician’s judgement may not always be determined from the medical notes. However, even taking this limitation into account, it is apparent that a significant number of patients are not on appropriate thromboprophylaxis on admission and that patients are leaving hospital still on inadequate treatment. Inadequate treatment should be identified on admission to hospital and modified accordingly or recommendations fed back to primary care. We felt this was lacking and may reflect the fact that many patients with AF are being managed by general physicians and not by cardiologists. The view that warfarin treatment is more harmful than beneficial because of bleeding risks may still pervade.

Conclusions

AF is a frequently encountered problem in acute medical admissions. Patients presenting with a new diagnosis were generally managed consistently with the NICE guidelines for rate control and thromboprophylaxis. For patients with pre-existing AF, analysis of their management in the community revealed poor compliance with NICE guidelines for rate control and thromboprophylaxis.

Inadequate thromboprophylaxis may well reflect lack of familiarity with the NICE stroke risk algorithm. Promoting the use of a well-validated, more memorable stroke risk stratification scheme, such as the CHADS2 scoring system,9 might improve compliance with this standard. Also, promoting the assessment of the risk of bleeding with warfarin in relevant patients using scoring systems such as in the HEMORR2HAGES scoring system,10 may allow physicians to anticoagulate more patients with AF with less fear of bleeding complications.

Key messages

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines on management of atrial fibrillation (AF) recommend the use of beta blockers or non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers for rate control of AF and stress the importance of reducing cardioembolic risk

Our audit suggests digoxin is still used as first-line treatment in many patients and suboptimal thromboprophylaxis occurred in more than half of the audit population

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- Kannel WB, Benjamin EJ. Status of the epidemiology of atrial fibrillation. Med Clin North Am 2008;92:17–40, ix.

- National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Atrial fibrillation: national clinical guideline for management in primary and

secondary care. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2006. - Lim H, Hamaad A, Lip G. Clinical review: clinical management of atrial fibrillation – rate control versus rhythm control. Crit Care 2004;8:271–9.

- Aguilar MI, Hart R. Oral anticoagulants for preventing stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and no previous history of stroke or transient ischemic attacks. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(3):CD001927.

- Aguilar MI, Hart R. Antiplatelet therapy for preventing stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and no previous history of stroke or transient ischemic attacks. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(4):CD001925.

- Aguilar MI, Hart R, Pearce LA. Oral anticoagulants versus antiplatelet therapy for preventing stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and no history of stroke or transient ischemic attacks. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(3):CD006186.

- Saxena R, Koudstaal PJ. Anticoagulants versus antiplatelet therapy for preventing stroke in patients with non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation and a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(4):CD000187.

- Hart RG, Pearce LA, Rothbart RM, McAnulty JH, Asinger RW, Halperin JL. Stroke with intermittent atrial fibrillation: incidence and predictors during aspirin therapy. Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:183–7.

- Rietbrock S, Heeley E, Plumb J, van Staa T. Chronic atrial fibrillation: incidence, prevalence, and prediction of stroke using the Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age >75, Diabetes mellitus, and prior Stroke or transient ischemic attack (CHADS2) risk stratification scheme. Am Heart J 2008;156:57–64.

- Gage BF, Yan Y, Milligan PE et al. Clinical classification schemes for predicting hemorrhage: results from the national registry of atrial fibrillation (NRAF). Am Heart J 2006;151:713–19.