Plasma natriuretic peptide (NP) testing is not widely used in heart failure clinical practice in the UK or Ireland, despite a large evidence base. This article reports the views of a consensus group that was set up to develop guidance on the place of NP testing for clinicians in primary and secondary care.

Monthly Archives: March 2010

Whatever happens to the cardioverted? An audit of the success of direct current cardioversion for atrial fibrillation in a district general hospital over a period of four years

March 2010Br J Cardiol 2010;17:86–8 2 CommentsDirect current cardioversion (DCCV) to restore sinus rhythm (SR) in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation (AF) remains a therapeutic option, though recent studies have questioned its need and value in the longer term.

Audit of management of atrial fibrillation at a district general hospital

March 2010Br J Cardiol 2010;17:89–92 Leave a commentAtrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia and is a major risk factor for stroke. The 2006 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines on management of AF recommended the use of beta blockers and calcium channel blockers in preference to digoxin for first-line rate control and emphasised the importance of appropriate thromboprophylaxis.

We audited management of AF at the Royal Surrey County Hospital against standards derived from the NICE guidelines. Fifty-nine of the 663 patients (8.9%) presenting to the acute medical take during the month of May 2008 had a documented diagnosis of AF, 10% of whom presented with a new diagnosis of AF and 90% of whom had a pre-existing diagnosis. The case notes of these 59 patients were reviewed.

All patients with a new diagnosis of AF were managed consistently with the NICE guidelines. Compliance for patients with pre-existing AF was much lower. Eighteen out of 31 patients (58%) with pre-existing AF were found to be on digoxin monotherapy on admission. Inadequate thromboprophylaxis on admission was found in 51% of all patients with pre-existing AF.

These results indicate compliance with NICE guidelines can be improved and a need for raised awareness in the community, particularly with regard to risk stratification for thromboprophylaxis.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia with a reported prevalence of 0.4–1% in the general population, increasing with age to afflict 9% of the population aged 80 years and over.1 It represents a significant risk factor for stroke if left untreated.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines for management of AF were issued in June 2006 and placed particular importance on the use of beta blockers and non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers as first-line rate control agents in preference to digoxin.2 Digoxin is as effective as beta blockers and calcium channel blockers in controlling heart rate during normal daily activities, but is less effective than these agents at high levels of physical exertion.3

The guidelines also emphasised the importance of assessment for, and initiation of, thromboprophylaxis with correct risk stratification. AF is an independent risk factor for stroke and the benefits of thromboprophylaxis in AF patients are well established.4,5 For both primary and secondary prevention, warfarin is more effective than aspirin in reducing risk of stroke,6,7 though it may be associated with increased risk of bleeding, and in a Cochrane review comparing warfarin and aspirin for primary prevention in patients with non-rheumatic AF, all-cause mortality was similar for the two groups.6

Patients with paroxysmal AF are at the same risk of thromboembolic events as patients with persistent AF and, hence, risk stratification should be conducted according to the same criteria and not guided by the frequency or duration of paroxysms.8

We performed an audit regarding two important aspects of the management of patients with AF presenting to the acute medical take at the Royal Surrey County Hospital against standards derived from the NICE guidelines.2 They were:

- All patients who are prescribed digoxin as initial monotherapy for rate-control are to have the reason for this prescription recorded where it is not obvious (for example, a sedentary lifestyle or presence of contraindications to alternative agents).

- All patients should be assessed for risk of stroke/thromboembolism and given thromboprophylaxis according to the NICE stroke risk stratification algorithm,2 which classifies patients into low, moderate and high thromboembolic risk groups. Low-risk patients are <65 years with no risk factors. High-risk patients are those with a history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA), or those >75 years with hypertension, diabetes mellitus or vascular disease, or those with heart failure or valve disease. Aspirin is recommended for low-risk patients and warfarin for high-risk patients. Moderate risk patients are those who are >65 years with no risk factors, or those who are <75 years with hypertension, diabetes or vascular disease. Either aspirin or warfarin is recommended for thromboprophylaxis in this group and treatment can be decided on an individual basis.

Methods

All patients presenting to the acute medical take under the care of all physicians during the month of May 2008 were screened for a documented diagnosis of AF. Patients with a documented diagnosis of paroxysmal AF but who were in sinus rhythm on admission were included in the AF cohort. Patients with atrial flutter were excluded. Case notes and discharge summaries for the AF patients were reviewed post-discharge to collate information using a standardised proforma.

Results

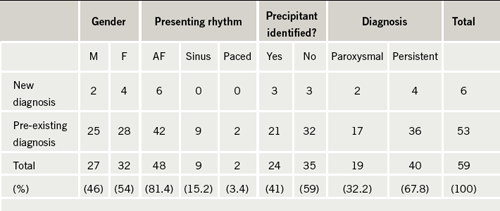

Six hundred and sixty-three patients presented to the acute medical take in the month of May 2008, 59 of whom were identified as having a primary or an additional diagnosis of AF, equating to 8.9%, which is consistent with the reported prevalence of AF.1 The demographics of these patients are shown in table 1. Fifty-three patients (90%) had a pre-existing diagnosis, while just six (10%) had a new diagnosis made during admission. The mean age was 80 years (range 31–95 years). Forty of the patients (67.8%) had persistent or permanent AF and 19 (32.2%) had paroxysmal AF. A precipitant for AF was identified in 24 patients (41%); the precipitant in the vast majority of these patients was chest infection.

Standard 1: All patients who are prescribed digoxin as initial monotherapy for rate-control are to have the reason for this prescription recorded

Three of the patients with new AF were started on a rate-control strategy (two with a beta blocker and one with a beta blocker plus digoxin). One patient with new AF was started on a rate plus rhythm control strategy with a calcium channel blocker and intended elective direct current cardioversion. Compliance was therefore 100% with this standard for patients with new AF.

There were 31 patients with pre-existing AF. Digoxin monotherapy was deemed ‘appropriate’ where there was documentation of contraindications to beta blockers and calcium channel blockers, or documentation of a sedentary lifestyle. In the absence of both these criteria, or where the patient was found to have paroxysmal as opposed to persistent or permanent AF, digoxin monotherapy was deemed ‘inappropriate’. Eighteen of these patients (58%) were found to be on digoxin monotherapy on admission and according to the above criteria, this was ‘appropriate’ in just nine patients. Digoxin monotherapy was found to be ‘inappropriate’ in the other nine patients: six of them were not sedentary and had no contraindications to beta blockers and calcium channel blockers, and the other three patients had a diagnosis of paroxysmal AF and were in sinus rhythm on admission.

We also found four patients with paroxysmal AF who had progressed to permanent AF and who were started on rate control during admission having previously been on rhythm control only or no treatment. Two of these patients were started on a beta blocker and two on digoxin monotherapy, one appropriately (a sedentary patient) but another inappropriately (not sedentary and no contraindications to beta blockers or calcium channel blockers).

Standard 2: All patients should be assessed for risk of stroke/thromboembolism and given thromboprophylaxis according to the stroke risk stratification algorithm

Each patient’s case notes were reviewed carefully to establish whether or not thromboprophylaxis was consistent with the NICE stroke risk stratification algorithm.2 In a minority of cases (9%) it was not clear cut whether or not thromboprophylaxis was appropriate; this was usually in patients at increased risk of harm from warfarin or aspirin but where these risks could potentially be outweighed by the benefits (such as in patients at high risk of thromboembolism with previous but not active peptic ulceration). These patients were classified as being ‘difficult clinical decisions’.

All of the patients with a new diagnosis of AF were started on thromboprophylaxis that was consistent with the algorithm. Five of the six patients were classified as ‘high risk’: three were started on warfarin; two were started on aspirin due to contraindications to warfarin; and one was started on aspirin but with a view to delayed consideration of warfarin as they had presented with a new stroke. One patient was classified as ‘moderate risk’ and he was started on aspirin appropriately.

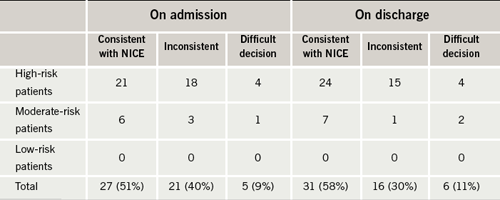

Compliance with this standard was lower for the patients with pre-existing AF. The majority of these patients were also stratified as ‘high risk’ (81%) with the remainder classified as ‘moderate risk’ (19%) and none as ‘low risk’. As shown in table 2, on admission, only 27 patients (51%) were being managed consistent with the NICE stroke risk algorithm, while 21 (40%) were not. Five patients (9%) fell into the ‘difficult decision’ category. These figures improved on discharge indicating that some of the patients were having their risk re-assessed and medication changed appropriately, but they still fell short of the standard with just 31 patients (58%) managed consistently with the algorithm on discharge.

Discussion

We performed a detailed case note review of 59 patients with AF presenting to the acute medical take of a district general hospital over a month-long period and evaluated management of their AF against standards derived from the NICE guidelines. The majority of these patients (90%) had a pre-existing diagnosis of AF.

For patients with a new diagnosis of AF, compliance with Standard 1 was good: none were discharged on digoxin monotherapy. Likewise, regarding Standard 2, all patients were given thromboprophylaxis consistent with the NICE stroke risk algorithm. An obvious limitation of the results for this group of patients is the small size of the cohort; our results imply, however, that practice is generally consistent with the NICE guidelines.

For patients with pre-existing AF, analysis of this larger group of 53 patients indicated that management of AF in the community has poor compliance with NICE guidelines. Regarding Standard 1, 18 of the patients admitted were found to be on digoxin monotherapy in the community. In nine of these patients (50%) digoxin monotherapy was ‘inappropriate’ as there were no documented contraindications to beta blockers and calcium channel blockers and they did not have a sedentary lifestyle, or they had paroxysmal AF. It was not always apparent whether digoxin had been started in primary or secondary care and it is important to consider that there may well be other reasons not documented as to why some of these patients were on digoxin (for example, they might have been tried on a beta blocker in the community but changed to digoxin due to poor tolerance of the side effects – this information would not necessarily be found in the hospital notes). Furthermore, most patients with AF have traditionally been treated with digoxin as first-line treatment in the past and our finding reflects this practice.

Only two of the nine patients with no obvious reason for digoxin monotherapy had their medication reviewed and changed during admission to treatment compliant with the NICE guidelines while the remaining seven were continued on digoxin. There are many reasons why an acute hospital admission may not be an appropriate juncture at which to change management: the patient may have been stable on digoxin for years; digoxin may have been chosen over an alternative rate-control agent for reasons not apparent in the hospital notes; and the patient may have presented a problem entirely unrelated to their AF. Further evaluation of heart rate control may be necessary in some patients before a blanket change from digoxin to a beta blocker or calcium channel blocker. However, an acute admission could be effectively utilised as an opportunity to review medication and either amend management or make recommendations for primary care on the discharge letter. There is no guidance from NICE as to whether digoxin should be replaced in patients already receiving this medication.

Compliance with Standard 2 was also poor. Of the 53 patients with pre-existing AF, just 27 (51%) were on appropriate thromboprophylaxis. There was some improvement in the number of patients on appropriate thromboprophylaxis on discharge (31 patients) indicating that some clinicians were re-assessing risk during admission and modifying thromboprophylaxis appropriately, but the number is still too low. Of particular concern were two patients admitted and discharged without any thromboprophylaxis despite an absence of contraindications to aspirin or warfarin.

There is often a reluctance to use warfarin for fear of bleeding complications and the reasons for not starting thromboprophylaxis may be based on a clinician’s judgement. Important subjective considerations impacting on the clinician’s judgement may not always be determined from the medical notes. However, even taking this limitation into account, it is apparent that a significant number of patients are not on appropriate thromboprophylaxis on admission and that patients are leaving hospital still on inadequate treatment. Inadequate treatment should be identified on admission to hospital and modified accordingly or recommendations fed back to primary care. We felt this was lacking and may reflect the fact that many patients with AF are being managed by general physicians and not by cardiologists. The view that warfarin treatment is more harmful than beneficial because of bleeding risks may still pervade.

Conclusions

AF is a frequently encountered problem in acute medical admissions. Patients presenting with a new diagnosis were generally managed consistently with the NICE guidelines for rate control and thromboprophylaxis. For patients with pre-existing AF, analysis of their management in the community revealed poor compliance with NICE guidelines for rate control and thromboprophylaxis.

Inadequate thromboprophylaxis may well reflect lack of familiarity with the NICE stroke risk algorithm. Promoting the use of a well-validated, more memorable stroke risk stratification scheme, such as the CHADS2 scoring system,9 might improve compliance with this standard. Also, promoting the assessment of the risk of bleeding with warfarin in relevant patients using scoring systems such as in the HEMORR2HAGES scoring system,10 may allow physicians to anticoagulate more patients with AF with less fear of bleeding complications.

Key messages

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines on management of atrial fibrillation (AF) recommend the use of beta blockers or non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers for rate control of AF and stress the importance of reducing cardioembolic risk

Our audit suggests digoxin is still used as first-line treatment in many patients and suboptimal thromboprophylaxis occurred in more than half of the audit population

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- Kannel WB, Benjamin EJ. Status of the epidemiology of atrial fibrillation. Med Clin North Am 2008;92:17–40, ix.

- National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Atrial fibrillation: national clinical guideline for management in primary and

secondary care. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2006. - Lim H, Hamaad A, Lip G. Clinical review: clinical management of atrial fibrillation – rate control versus rhythm control. Crit Care 2004;8:271–9.

- Aguilar MI, Hart R. Oral anticoagulants for preventing stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and no previous history of stroke or transient ischemic attacks. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(3):CD001927.

- Aguilar MI, Hart R. Antiplatelet therapy for preventing stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and no previous history of stroke or transient ischemic attacks. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(4):CD001925.

- Aguilar MI, Hart R, Pearce LA. Oral anticoagulants versus antiplatelet therapy for preventing stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and no history of stroke or transient ischemic attacks. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(3):CD006186.

- Saxena R, Koudstaal PJ. Anticoagulants versus antiplatelet therapy for preventing stroke in patients with non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation and a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(4):CD000187.

- Hart RG, Pearce LA, Rothbart RM, McAnulty JH, Asinger RW, Halperin JL. Stroke with intermittent atrial fibrillation: incidence and predictors during aspirin therapy. Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:183–7.

- Rietbrock S, Heeley E, Plumb J, van Staa T. Chronic atrial fibrillation: incidence, prevalence, and prediction of stroke using the Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age >75, Diabetes mellitus, and prior Stroke or transient ischemic attack (CHADS2) risk stratification scheme. Am Heart J 2008;156:57–64.

- Gage BF, Yan Y, Milligan PE et al. Clinical classification schemes for predicting hemorrhage: results from the national registry of atrial fibrillation (NRAF). Am Heart J 2006;151:713–19.

Femoral artery dissection – an uncommon but well-recognised complication of coronary angiography

March 2010Br J Cardiol 2010;17:93 1 CommentCoronary angiography is commonly performed via the right femoral artery. Under local anaesthetic, the arterial lumen is initially cannulated with a wide-bore needle, then a long and soft J wire is inserted through the needle. The needle is then removed, and an arterial sheath is passed over the wire using a Seldinger technique.

Very rarely, the needle can displace following successful intraluminal cannulation. If the wire does not easily pass, it is important never to force it. Such an event occurred on this occasion.

Following an unsuccessful attempt to pass the wire, contrast was injected through the needle. This demonstrated dissection of the common femoral artery, characterised by contrast holdup post-injection, due to contrast staying in one of the layers between arterial tunica intima and tunica adventitia (figure 1).

This was managed by removing the needle and externally compressing the artery with digital pressure. The patient made a full recovery, and had coronary angiography successfully performed via his left femoral artery.

Localised femoral artery dissection is an uncommon but well-recognised complication of coronary angiography, and usually resolves with external manual compression.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Brady/tachyarrhythmia preceding the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoid

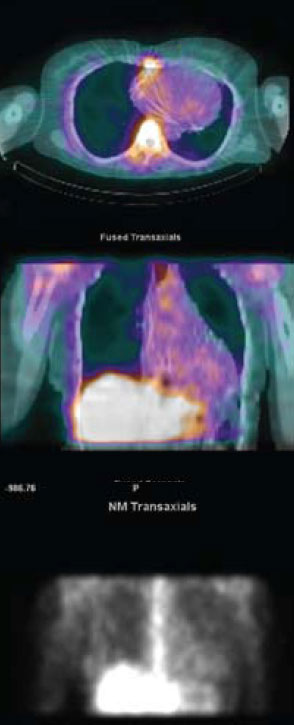

March 2010Br J Cardiol 2010;17:94–6 Leave a commentCardiac sarcoid remains a notoriously difficult to diagnose condition and arrhythmias remain an important initial presentation. It is amenable to treatment therefore it is important to make an early diagnosis to reduce morbidity and mortality.

Case report

A 51-year-old Asian woman presented with intermittent presyncope and profound breathlessness. She had no significant past medical history of note and was not receiving any regular medication. A resting 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed a second-degree atrioventricular block. She subsequently underwent insertion of a dual-chamber permanent pacemaker. Further investigations at that time revealed unobstructed coronary arteries on angiography and normal ventricular function on transthoracic echocardiography.

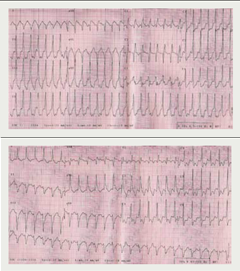

Her symptoms initially improved but relapsed one year later with breathlessness, presyncope but now intermittent rapid palpitation. A 24-hour Holter monitor revealed symptomatic rapid polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (figure 1). She consequently had her pacemaker upgraded to a biventricular internal defibrillator.

Despite biventricular pacing and adequate heart rate control with anti-arrhythmic medication, she continued to remain significantly breathless on minimal exertion prompting further investigation including pulmonary function tests, which revealed normal lung volumes and gas exchange.

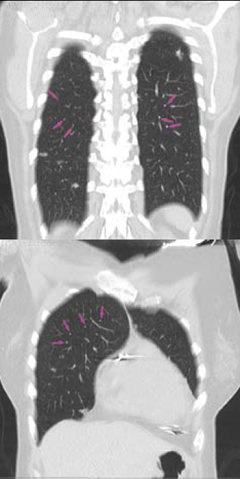

A plain chest radiograph revealed diffuse interstitial infiltration. Upon thoracic high-resolution computed tomography there were typical abnormalities consistent with pulmonary sarcoid disease with enlarged paratracheal, subcarinal and aortic pulmonary lymphadenopathy

(figure 2). Cardiac involvement was confirmed on myocardial scintigraphy with gallium demonstrating abnormal myocardial tracer uptake

(figure 3). Steroid therapy was commenced with pulsed methylprednisolone alongside further anti-arrhythmic medication with a significant improvement in symptoms.

Discussion

All patients presenting with cardiac arrhythmias should be investigated in order to identify any underlying cardiac disease. Cardiac sarcoid may be the initial clinical manifestation of systemic sarcoidosis and a tachy- or bradyarrhythmia may be the first indication of its presence.

Cardiac sarcoid is more common than previously recognised, presenting not infrequently with sudden cardiac death. It is less likely to be diagnosed ante-mortem because less than 10% of patients have cardiovascular symptoms.1,2 It is, therefore, important to recognise overt and non-specific symptoms such as chest pain, breathlessness, palpitations and dizziness, and investigate appropriately.

Arrhythmias are an important clinical presentation in patients who have sarcoid disease with cardiac involvement, and virtually every type of arrhythmia has been documented.2,3 Fleming reviewed 138 fatalities out of 300 patients in whom a diagnosis of cardiac sarcoid had been made in life or at necropsy, and found that, at presentation, 73% had ventricular or supraventricular arrhythmias, 26% had complete heart block and 61% had left or right bundle branch blocks. Sudden death had occurred in 77 cases, and in 49 of these cardiac sarcoidosis had not been diagnosed previously.2 Uusimaa et al. described nine patients with cardiac sarcoid whose initial presentation was of ventricular tachyarrhythmia without any detectable systemic findings.4

It is important to note that not all patients who have documented arrhythmias may present with symptoms as Mikhail et al. revealed in a study of 147 consecutive patients diagnosed with sarcoidosis. In these patients, 9.5% presented with ECG abnormalities, however, 72% of these patients had no cardiac symptoms.1 While 41 of 80 patients published by Stein et al. with cardiac sarcoid had conduction and repolarisation abnormalities, none had clinical symptoms of cardiac disease.5

Clearly, the initial absence of systemic symptoms or signs of sarcoidosis posed a diagnostic conundrum in our patient. Furthermore, insertion of a pacemaker in the absence of a firm diagnosis effectively eliminated the use of cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) at her next presentation.

CMR remains a useful diagnostic and monitoring tool in evaluating patients with cardiac sarcoid as demonstrated by Matsuki and Matsuo.6 The improvement or stability on follow-up CMR images post treatment has been correlated to clinical features and found useful as shown by Vignaux et al., but the significance may have to be tested in a larger trial.7

Gadolinium enhancement improves accuracy and localisation of granulomatous lesions and can be used as a guide to obtaining endomyocardial biopsy specimens. However, the proportion of patients with evidence of granulomatous cardiac lesions remains small. Hagemann and Wurm, in a review of 702 patients, reported that, while 5% had clinical evidence of cardiac sarcoidosis, only 15% had cardiac lesions at necropsy.8 Scadding and Mitchell reported a far worse percentage with four of the 500 patients reviewed having such evidence.9

Radionuclide tests with thallium and gallium have been widely used to demonstrate infiltration of myocardial tissue. The theory of reverse distribution of thallium on exercise or infusion of dipyridamole or adenosine has also been used to great effect in aiding diagnosis, and in the presence of normal coronary arteries this has a higher sensitivity. However, a normal scan does not exclude the presence of myocardial involvement nor does a positive scan add prognostic value.10

The goals of treatment for cardiac sarcoid are to reduce the extent of the disease in myocardial tissue, control of heart failure and establish rhythm management. Corticosteroids have played an important role in treatment of sarcoid disease, however, evidence for use remains anecdotal. In individual cases and small series, they have been shown to reverse mechanical and electrical abnormalities, however, prolonged use has also been reported to lead to increased risks of ventricular aneurysms.11,12 Immunosuppressants and cytotoxic agents have also been used as steroid-sparing agents.13

Anti-arrhythmic drugs reduce the risk of sudden cardiac death by abolishing fatal arrhythmias. This treatment alone has been insufficient in most reports because the majority of these arrhythmias are ventricular in origin, often incessant and drug refractory.1 Device therapy with pacemakers and automated cardiac defibrillators should thus be employed as there is also evidence that prognosis is improved.14 Catheter ablation procedures for refractory lethal arrhythmias may sometimes be necessary as an adjunct.15

In patients with heart failure, conventional pharmacotherapy with beta blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and diuretics remain the mainstay of treatment. Some patients may require heart transplantation where extensive myocardial involvement may be unresponsive to the aforementioned therapies. These patients often do well with a low recurrence of disease in the allograft.16

Overall, the diagnostic and treatment modalities of cardiac sarcoid in the last 10 years remain similar and no current literature has followed up patients who have been subjected to a standardised management strategy.18,19 The available data on prognosis are, thus, variable, with some reports quoting five-year survival rates ranging between 2 and 40%.2,12,17

The authors conclude that cardiac sarcoid remains notoriously difficult to diagnose and we recommend a high index of suspicion in order to achieve this. Prompt diagnosis, expert assessment and early aggressive treatment may improve prognosis and, as such, it is important to investigate extensively for structural heart disease in patients who present with unexplained arrhythmias.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Kshama Wechalekar and Dr Michael Rubens for providing the radiology images. We would also like to acknowledge the contribution of Dr Paul Oldershaw in reading through this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- Mikhail JR, Mitchell DN, Bull KP. Abnormal electrocardiographic findings in sarcoidosis. In: Kiwai, Hosoda Y, eds. Proceedings of 6th international conference on sarcoidosis. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1974:365–72.

- Fleming HA. Death from sarcoid heart disease. United Kingdom series 1971–1986. 300 cases with 138 deaths. In: Grassi C, Rizzato G, Pozzi E, eds. Sarcoidosis and other granulomatous disorders. 11th world congress. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1988:19.

- Uusimaa P, Ylitalo K, Anttonen O et al. Ventricular tachyarrhythmia as a primary presentation of sarcoidosis. Europace 2008;10:760–6.

- Suzuki T, Tsugiyasu K, Kubata S et al. Holter monitoring as a noninvasive indicator of cardiac involvement in sarcoidosis. Chest 1994;106:1021–4.

- Stein E, Jackler I, Stimmel B, Stein W, Siltzbach LE. Asymptomatic electrocardiographic alterations in sarcoidosis. Am Heart J 1973;86:474–7.

- Matsuki M, Matsuo M. MR findings of myocardial sarcoidosis. Clin Radiol 2000;55:323–5.

- Vignaux C, Dhote R, Duboc D et al. Clinical significance of myocardial magnetic resonance abnormalities in patients with sarcoidosis: a 1-year follow-up study. Chest 2002;122:1895–901.

- Hagemann GJ, Wurm K. The clinical, electrocardiographic and pathological features of cardiac sarcoidosis. In: Jones Williams W, Davies BH, eds. Sarcoidosis and other granulomatous diseases. 8th international conference. Cardiff: Alpha Omega, 1980:601.

- Scadding JG, Mitchell DN. The heart. In: Sarcoidosis. 2nd ed. London: Chapman and Hall, 1985:329–48.

- Okayama K, Kurata C, Tawarahara K. Diagnostic and prognostic value of myocardial scintigraphy with thallium 201 and gallium 67 in cardiac sarcoidosis. Chest 1995;107:330–4.

- Shammas RL, Movahed A. Successful treatment of myocardial sarcoidosis with steroids. Sarcoidosis 1994;11:37–9.

- Roberts WC, McAllister HA Jr, Ferrans VJ. Sarcoidosis of the heart: a clinicopathologic study of 35 necropsy patients (group 1) and review of 78 previously described necropsy patients (group 11). Am J Med 1977;63:86–108.

- Baughman RP, Ohmichi M, Lower EE. Combination therapy for sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2001;18:133–7.

- Winters SL, Cohen M, Greenberg S et al. Sustained ventricular tachycardia associated with sarcoidosis: assessment of the underlying cardiac anatomy and the prospective utility of programmed ventricular stimulation, drug therapy and an implantable antitachycardia device. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991;18:937–43.

- Koplan BA, Soejima K, Baughman K, Epstein LM, Stevenson WG. Refractory ventricular tachycardia secondary to cardiac sarcoid: electrophysiologic characteristics, mapping, and ablation. Heart Rhythm 2006;3:924–929 B.

- Valantine HA, Tazelaar HD, Macoviak J et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis: response to steroids and transplantation. J Heart Transplant 1987;6:244–50.

- Yazaki Y, Isobe M, Hiroe M et al. Prognostic determinants of long-term survival in Japanese patients with cardiac sarcoidosis treated with prednisone. Am J Cardiol 2001;88:1006–10.

- Baughman R. Therapeutic options for sarcoidosis: new and old. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2002;8:464–9.

- Mitchell DN, du Bois RM, Oldershaw PJ. Cardiac sarcoidosis—a potentially fatal condition that needs expert assessment. BMJ 1997;21:314–20.

Aspirin – reassessing its role in cardiovascular disease

March 2010Br J Cardiol 2009;17(Suppl 1):S1-S3 Leave a comment

Report from a scientific roundtable meeting held at the Royal Society of Medicine, London, in October 2009.

Introduction

Aspirin was developed in 1897 but, despite many years of widespread use, the full therapeutic potential of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) is still being uncovered and important uncertainties remain about its therapeutic role. Its efficacy in secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease is unchallenged but a recent meta-analysis has prompted questions about the place of low-dose aspirin as primary prevention of cardiovascular disease – in particular, about the balance of risk and benefit in people with diabetes.1

Some people do not derive the expected benefit from aspirin prophylaxis but we do not fully understand why this is the case.

This roundtable meeting, convened by the Aspirin Foundation and the British Journal of Cardiology, was sponsored by Bayer Health Care. It reviewed current knowledge about the role of aspirin in the management of cardiovascular disease.

Professor Peter Elwood (Department of Epidemiology, Cardiff University), who chaired the meeting, expressed concerns about the interpretation of recent data. He questioned whether the positive and negative outcomes observed with use of aspirin were compared fairly. There had been little consideration of the possible benefit of reducing bleeding risk by eradicating H. pylori and the potential reduction in cancer risk with long-term aspirin use was being ignored.

In his view, reporting of new evidence about aspirin in the lay media had been biased and negative, though his experience with citizens’ juries had convinced him that an educated and informed public can make rational decisions about the risks and benefits of treatment. There remains much to learn about the most effective ways of using aspirin, he concluded.

Reference

- Calvin AD, Aggarwal NR, Murad NH et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing patients with and without diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009 Sep 9; published online ahead of print.

How do antithrombotics work?

March 2010Br J Cardiol 2009;17(Suppl 1):S3-S4 Leave a comment

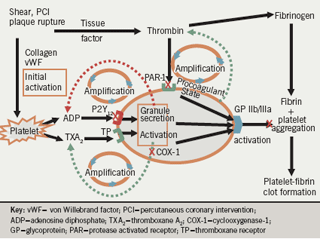

Antithrombotic drugs act principally by inhibiting platelet function directly (for example, aspirin, clopidogrel and dipyridamole) or, via thrombin inhibition, by inhibiting platelet activation and fibrin formation (for example, heparins, warfarin and direct inhibitors of thrombin or factor Xa). Aspirin and other antiplatelet drugs reduce the risk of cardiovascular events such as thrombus formation (figure 1) by approximately 25 per cent in both primary and secondary prevention.(1) Inhibiting more than one pathway at a time significantly increases efficacy: dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin plus clopidogrel is more effective than aspirin monotherapy in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS)(2) and aspirin plus dipyridamole is more effective than aspirin for secondary prevention of stroke.(3) All antiplatelet therapies are associated with an increased risk of bleeding; whereas the balance of benefit and the increased risk of bleeding is clear for secondary prevention, it is less certain for primary prevention.

Mechanisms

The mechanism of action of aspirin differs from that of other antiplatelet agents. Aspirin irreversibly acetylates platelet cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1), completely inhibiting COX-1- dependent synthesis of thromboxane A2 (TXA2), a substance which is a potent vasoconstrictor and promoter of platelet aggregation. Whether low-dose aspirin also exerts a significant anti-inflammatory effect is uncertain: a retrospective sub-analysis suggested that it was more effective in primary prevention in individuals who had high levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) at baseline4 but it is not known whether low-dose aspirin reduces plasma CRP or other markers of inflammation. A current analysis of the Aspirin in Asymptomatic Atherosclerosis (AAA) study, which serially collected measurements of CRP and other biomarkers in 3,300 participants, should provide more evidence on this question within the next year.

The mechanism of action of dipyridamole is complex but, in summary, it appears to decrease platelet exposure to adenosine diphosphate (ADP) by inhibition of phosphodiesterase in red cells and reduction of ADP release.

Other antiplatelet agents inhibit the interaction between platelets and ADP by blocking the P2Y12 receptor. This membrane G-protein is involved not only in ADP-induced platelet aggregation but also in platelet secretion of pro-thrombotic factors independent of TXA2 (providing a mechanism for synergy with aspirin), stabilisation of platelet aggregates induced by thrombin, and inhibition of shear-induced aggregation. Ticlopidine, the first agent in this thienopyridine class, is associated with bone marrow toxicity and has been replaced by clopidogrel. Both are prodrugs, requiring biotransformation to metabolites that block P2Y12 receptors irreversibly. Clinical limitations include a delayed onset of action (though this is reduced by a loading dose of clopidogrel in patients with ACS) and a variable clinical response due to interindividual differences in metabolism of the prodrugs. Further, prolonged inhibition of platelet function increases the risk of bleeding in patients who subsequently undergo coronary intervention or peripheral arterial bypass grafting.

Newer agents have been developed to overcome these limitations. Prasugrel, another thienopyridine, has a faster onset of action than clopidogrel. The Trial to assess improvement in therapeutic outcomes by optimizing platelet inhibition with prasugrel—thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TRITON-TIMI 38), which included high-risk patients with ACS requiring percutaneous coronary intervention, showed that prasugrel reduced ischaemic events, though at the cost of a higher risk of major and fatal bleeding complications.5 A further study is now underway which may identify a patient group at lower risk of bleeding: Targeted platelet inhibition to clarify the optimal strategy to medically manage acute coronary syndromes (TRILOGY-ACS) involves patients with ACS for whom no revascularisation is planned (www.trilogyacstrial.org).

New ADP antagonists include direct antagonists of the P2Y12 receptor such as cangrelor (administered intravenously) and ticagrelor (orally). These agents are now undergoing clinical trials to compare them with clopidogrel in patients with ACS. Other newer antiplatelet agents include glycoprotein GP IIb/IIIa antagonists such as the monoclonal antibody abciximab, currently used to treat high-risk patients with ACS. Abciximab is administered intravenously; oral GP IIb/IIIa antagonists have not proved clinically useful.

Anticoagulants

These agents are usually considered to act by inhibiting fibrin formation but, because they primarily inhibit thrombin formation, they also reduce platelet activation. Heparins act indirectly by catalysing the actions of antithrombin: this is a natural coagulation inhibitor that inhibits not only thrombin but also factors Xa, IXa and XIa. Orally active vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin also act indirectly, by reducing hepatic synthesis of factors II, VII, IX and X. These agents have been in clinical use for many years; they remain valuable therapies for the prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism, and low molecular weight heparins have an established role in the management of ACS. In acute stroke the benefit of heparins is outweighed by the risk of major bleeding episodes except in patients who are at high risk due, for example, to a history of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. The commonest indication for oral anticoagulants is reduction of stroke risk in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation.

The clinical limitations of heparin and warfarin include inter-individual variability in coagulation inhibition (caused by genes, age, weight, diet, and interactions with other drugs) and intra-individual variability arising from pregnancy, impaired renal function and changes in diet and medication. As a result, it is necessary to monitor coagulation during warfarin therapy and sometimes to monitor renal function during treatment with heparin. Both agents cause increased bleeding, and much clinical time is devoted to manipulating anticoagulant therapy to reduce the risk of bleeding during surgery.

Fondaparinux, a parenteral direct factor Xa inhibitor introduced a few years ago, is used for the prevention of venous thrombosis and has shown encouraging results in the management of patients with ACS. There is great interest in new orally active agents such as the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran and the factor Xa inhibitor rivaroxaban. These are, by contrast with warfarin, effective in fixed doses and their anticoagulant effects do not need to be monitored. In the UK, they are licensed for prophylaxis of deep vein thrombosis in patients undergoing orthopaedic surgery and they are currently being evaluated in patients with atrial fibrillation. The recent Randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulation therapy (RE-LY) study showed that dabigatran was non-inferior to warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation, with greater safety at low doses.6

Conflict of interest

GL currently holds a University of Glasgow contract with Bayer as a member of a Drug Safety and Monitoring Committee for the MAGELLAN trial.

References

- Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet 2009;373:1849–60.

- The CURE Trial Investigators. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med 2001;345:494–502.

- Diener HC, Cunha L, Forbes C et al. European Stroke Prevention Study. 2. Dipyridamole and acetylsalicylic acid in the secondary prevention of stroke. Neurol Sci 1996;143:1–13.

- Ridker PM, Cushman M, Stampfer MJ et al. Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med 1997;336:973–9.

- Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH et al; TRITON-TIMI 38 Investigators. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2001–15.

- Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S et al; RE-LY Steering Committee and Investigators. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1139–51.

Aspirin – scope and limitations

March 2010Br J Cardiol 2009;17(Suppl 1):S8-S9 Leave a comment

Identifying targets in the thrombosis pathway Figure 1 summarises the central role of platelets in the genesis of thrombosis.1 The platelet is initially activated in response to shear stress, events … Continue reading Aspirin – scope and limitations

Identifying targets in the thrombosis pathway

Figure 1 summarises the central role of platelets in the genesis of thrombosis.1 The platelet is initially activated in response to shear stress, events such as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or plaque rupture, and the release of local agonists and exposure of the subendothelial components to flowing blood. Tissue factor ‘lights the fire’ by producing minute quantities of thrombin which then amplify the process. Binding of platelets to collagen and von Willebrand factor also leads to platelet activation; agents that block the interaction between platelets and these factors are now undergoing investigation.

Platelet activation and aggregation are amplified by adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and thromboxane A2 (TXA2), which act as secondary agonists on adjacent platelets. Thrombin has a pivotal role in platelet activation via PAR (protease activated receptor)-1 and PAR-4 receptors; drugs that block its interaction with PAR-1 receptors are now under investigation. The PAR-1 – thrombin interaction is largely unchecked by current oral antiplatelet therapy. Only parenteral glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa blockers potently and uniformly inhibit aggregation induced by thrombin. ADP, thromboxanes and thrombin (generated on the surface of platelets) all amplify the process of thrombosis. The final pathway leading to platelet aggregation is the interaction between the activated conformation of the GP IIb/IIIa receptor on the platelet membrane and the dimeric fibrinogen molecule and von Willebrand factor.

Thrombin converts fibrinogen to fibrin. Finally, the fibrin – platelet aggregate stabilises the clot and may lead to occlusion of the vessel. It is the combination of the vulnerable substrate within the vessel wall and the vulnerable, pro-thrombotic blood that is essential for the clinical occurrence of an occlusive thrombotic event.

Limitations of aspirin

Management guidelines agree closely on the role of aspirin in secondary prevention and have similar recommendations on its use as primary prevention, with some variation in risk thresholds at which treatment is indicated. Aspirin may also be recommended for atrial fibrillation when an oral anticoagulant is unsuitable. The American Heart Association recommends aspirin for primary prevention of ischaemic stroke in women (but not men) with sufficiently increased risk.

However, the ‘one size fits all’ and ‘one mechanism fits all’ approach may reflect the limitations of current evidence from clinical trials and our lack of understanding of the complete mechanisms of action of aspirin, respectively. The evidence for use of low-dose aspirin comes not from robust prospective data but primarily from meta-analyses and retrospective analyses. There is currently a huge controversy surrounding its role as primary prevention in patients with diabetes. More studies are needed, particularly to address the heterogeneity in thrombotic risk in this population. Underutilisation and low compliance with treatment with aspirin remain significant challenges.

Resistance measurement lacks specificity

Aspirin resistance should be defined in terms of insufficient pharmacological inhibition of platelet cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1)-dependent thromboxane synthesis. In the presence of aspirin, platelets utilise the COX-2 pathway to synthesise thromboxane and through this mechanism the antithrombotic efficacy of aspirin may be reduced. The Aspirin-induced platelet effect (ASPECT) study clearly showed that the detection of resistance depends on the method used: COX-1-specific methods utilising platelet-rich plasma and arachidonic acid as the agonist indicate a lower incidence of resistance than methods using whole blood,2,3 possibly due to the presence of unblocked COX-2. There was also a clear dose-dependent effect on platelet function in non-COX-1 specific assays such as collagen-induced aggregation, the platelet function analyser and urinary 11-dehydro-thromboxane B2.2

However, aspirin also exerts antithrombotic effects via non-COX mechanisms (figure 2). It has dose-dependent effects on collagen-, shear-, and ADP-induced aggregation (incompletely) and on thrombin generation, and it acetylates prothrombin, antithrombin, fibrinogen and factor XIII. It has been proposed that aspirin alters the function of the GP IIb/IIIa receptor and it affects clot permeability.2,4,5

The importance of compliance was illustrated by Tantry.6 In healthy volunteers, aspirin completely blocked arachidonic acid (AA)-induced platelet aggregation in platelet-rich plasma measured by turbidometric aggregometry and in whole blood measured by thromboelastography (TEG); complete inhibition was also evident among those patients who are fully compliant with treatment, both before and after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). AA-induced platelet aggregation was not inhibited in non-compliant patients before PCI; when these patients received a single 325 mg dose of aspirin after PCI, aggregation was completely inhibited 24 hours later.

Aspirin and diabetes

Platelets in patients with diabetes have increased reactivity as well as increased turnover. There is, however, a high level of uncertainty about the balance of benefit and risk of primary prevention with aspirin in this population and management guidelines have made conflicting recommendations.7

A recent meta-analysis found that the benefits of primary prevention with aspirin were similar for patients with or without diabetes8 and the Prevention of progression of arterial disease and diabetes (POPADAD) trial showed no benefit from aspirin in patients with diabetes and peripheral arterial disease.9 What could explain this? The ASPECT study compared platelet function in diabetic and non-diabetic patients and found a stronger dose-dependency among patients with diabetes, suggesting that these patients may need higher doses of aspirin.2 It is also possible that glycaemic control affects platelet function: platelet aggregation induced by ADP is higher in patients with glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1C) levels >7% compared with <7%, showing that poor glycaemic control is associated with higher platelet reactivity.10

Bleeding risk and higher doses

Evidence that higher doses of aspirin monotherapy (≥200 mg/day) are associated with an increased risk of bleeding compared with lower doses is unconvincing. Evidence for an increased risk was suggested in the presence of dual antiplatelet therapy from a subanalysis of the PCI-CURE study, which found a significant increase in risk of major bleeding among patients who received doses of ≥200 mg/day compared with those who received lower doses.11 The Clopidogrel for high atherothrombotic risk and ischaemia stabilisation, management and avoidance (CHARISMA) trial suggested that aspirin at doses of 100 mg/day or above may increase risk in patients taking dual therapy with clopidogrel.12 However, data from a true prospective study of aspirin dose suggest otherwise. The Clopidogrel optimal dose usage to reduce recurrent events/optimal antiplatelet strategy for intervention (CURRENT-OASIS 7) trial included 25,087 patients randomised in a 2 x 2 design to receive two dose regimens of clopidogrel with high-dose (300–325 mg/day) or low-dose (75–100 mg/day) aspirin; the primary endpoint was the incidence of ischaemic events after 30 days.13 There was no difference between aspirin doses for overall efficacy or bleeding risk, whereas bleeding risk was greater with high-dose clopidogrel.

Conflict of interest

PAG has a consulting agreement with Bayer and is paid by Bayer to be the Chairman of the adjudication committee of a major clinical trial funded by Bayer.

References

- Gurbel PA, Becker RC, Mann KG et al. Platelet function monitoring in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:1822–34.

- Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, DiChiara J et al. Evaluation of dose-related effects of aspirin on platelet function: results from the Aspirin-Induced Platelet Effect (ASPECT) study. Circulation 2007;115:3156–64.

- Lordkipanidzé M, Pharand C, Schampaert E et al. A comparison of six major platelet function tests to determine the prevalence of aspirin resistance in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J 2007;28:1702–08.

- Szczeklik A, Krzanowski M, Góra P et al. Antiplatelet drugs and generation of thrombin in clotting blood. Blood 1992;80:2006–11.

- Undas A, Brummel-Ziedins KE, Mann KG. Antithrombotic properties of aspirin and resistance to aspirin: beyond strictly antiplatelet actions. Blood 2007;109:2285–92.

- Tantry US, Bliden KP, Gurbel PA. Overestimation of platelet aspirin resistance detection by thrombelastograph platelet mapping and validation by conventional aggregometry using arachidonic acid stimulation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:1705–09.

- Nicolucci A, De Berardis G, Sacco M et al. AHA/ADA vs. ESC/EASD recommendations on aspirin as a primary prevention strategy in people with diabetes: how the same data generate divergent conclusions. Eur Heart J 2007;28:1925–7.

- Calvin AD, Aggarwal NR, Murad MH et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing patients with and without diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009 Sep 9; published online ahead of print.

- Belch J, MacCuish A, Campbell I et al. The prevention of progression of arterial disease and diabetes (POPADAD) trial: factorial randomised placebo controlled trial of aspirin and antioxidants in patients with diabetes and asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease. BMJ 2008;337:a1840. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1840.

- Singla A, Antonino MJ, Bliden KP, Tantry US, Gurbel PA. The relation between platelet reactivity and glycemic control in diabetic patients with cardiovascular disease on maintenance aspirin and clopidogrel therapy. Am Heart J 2009;158:784.e1–6.

- Jolly SS, Pogue J, Haladyn K et al. Effects of aspirin dose on ischaemic events and bleeding after percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the PCI-CURE study. Eur Heart J 2009;30:900–07.

- Steinhubl SR, Bhatt DL, Brennan DM et al; CHARISMA Investigators. Aspirin to prevent cardiovascular disease: the association of aspirin dose and clopidogrel with thrombosis and bleeding. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:379–86.

- Mehta SR. A randomized comparison of a clopidogrel high loading and maintenance dose regimen versus standard dose and high versus low dose aspirin in 25,000 patients with acute coronary syndromes: Results of the CURRENT OASIS 7 Trial. European Society of Cardiology Congress. Barcelona. 29 Aug – 02 Sep 2009.

Discussion

March 2010Br J Cardiol 2010;17(Suppl 1):S1-S12 Leave a comment

The efficacy of aspirin in secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease is well understood but its position in primary prevention of cardiovascular events is less clear.

Tailoring treatment

Insufficient pharmacological inhibition of platelet COX-derived thromboxane formation is often perceived as lack of effectiveness of antiplatelet therapy and is a major concern. Multiple factors, including lack of compliance, may contribute to this issue and true resistance is rare (1–2%). The assumption that a single dose is suitable for all patients is based on retrospective data and this assumption is now being challenged. For clopidogrel, even a 600 mg loading dose appears to be ineffective in some patients undergoing stent implantation but antiplatelet efficacy is not checked adequately before the procedure. It is estimated that 19% of the variation in response to clopidogrel is associated with variants in the 2C19 gene, for which 30% of Caucasians are heterozygous; it may be possible to genotype patients to identify those at risk.

Development of accurate but simple near-patient testing for platelet function that can be linked to patient outcomes is needed. This testing will identify patients who have not responded to antiplatelet therapy. Some current tests, such as VerifyNow, are convenient to use and produce a simple result; although popular with clinicians, it is difficult to understand what it means and there is marked interpatient and intrapatient variability. As understanding develops, platelet function testing may become as routine as measuring blood pressure. It is hoped that this will help clinicians tailor drug dosage to individual need and responsiveness and identify individuals who may require and benefit from more expensive agents.

Bleeding

The increased risk of bleeding associated with dual therapy with aspirin plus clopidogrel compared with monotherapy may possibly be attributable mainly to clopidogrel, and in particular to a high-dose clopidogrel regimen (600 mg), though this only appears to be significant in patients at high risk (such as acute coronary syndrome [ACS] patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI]). Although overall the incremental increase in risk associated with dual therapy compared with monotherapy is less than the incremental gain in benefit from the greater antithrombotic effect, treatment needs to be tailored to the individual patient and trial results are helpful in this respect. It is likely that such a high dose of clopidogrel is prescribed only because platelet function tests are uninformative.

Clinicians are rightly concerned about the risk of bleeding due to antiplatelet therapy but the occurrence of a stroke due to non-treatment is a more serious risk. Conversely, it is unknown how often minor bleeding events such as epistaxis or bleeding haemorrhoids cause patients to stop taking aspirin. More work is needed on presentation and interpretation of this risk. Further, it is not known whether the severity of gastrointestinal bleeding associated with antiplatelet agents differs from bleeding due to other causes. Older trials should be reanalysed to determine the severity of this end point and the findings should be considered in the design of prospective trials to clarify the balance of risk. The severity of events could be measured on a simple ordinal scale for morbidity and mortality.

New primary prevention trials of aspirin

The Critical Leg Ischaemia Prevention Study (CLIPS) showed that primary prevention with aspirin significantly reduced vascular events in patients with peripheral arterial disease1 but was not adequately recognised. Trials of low-dose aspirin now underway should provide new evidence about its role in primary prevention in the next 5–7 years. In the Aspirin to Reduce Risk of Initial Vascular Events (ARRIVE) study (www.arrive-study.com), efficacy and safety end points will be adjudicated. The ASCEND trial (A Study of Cardiovascular Events iN Diabetes), based in Oxford, (www.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/ascend) is a randomised trial that should provide the first reliable evidence about the effects of aspirin and of omega-3 fatty acids in diabetes. ASCEND aims to recruit at least 10,000 people with diabetes (either type 1 or type 2) who do not have known vascular disease.

In addition, ASPREE (ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly; http://www.med.monash.edu.au/epidemiology/cardiores/aspree) started in Australia in 2009 and will start in the US in 2010. It is a large-scale, double-blind primary prevention trial of aspirin versus placebo over a five-year treatment period conducted in 19,000 healthy elderly people aged 70 years and over. The purpose of the trial is to determine whether low-dose aspirin (100 mg/day) will extend the duration of healthy life in an ageing population. The study will examine whether the potential benefits of aspirin (particularly the prevention of heart disease, stroke and dementia) outweigh the risks of severe bleeding in this age group.

JPPP (Japanese Primary Prevention Project with aspirin in elderly patients with one or more risk factors for vascular events) is a four to five year nationwide, centrally randomised controlled trial evaluating the ability of low-dose, enteric-coated aspirin to prevent CVD events in elderly Japanese patients with hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and/or diabetes, comparing aspirin with placebo in approximately 10,000 patients aged 60-85 years. Primary end points include a composite of CVD death, non-fatal stroke and non-fatal MI. Additional study end points to be evaluated include non-CVD deaths, angina pectoris, transient ischaemic attacks, surgery or intervention for arteriosclerotic disease, and bleeding complications.

In summary, the results obtained in studies and meta-analyses are quantitatively in line with the beneficial results seen in secondary prevention, strongly suggesting that aspirin reduces the incidence of a first MI (and other vascular end points) in asymptomatic patients with vascular risk factors. In order to identify the appropriate target population in which the benefits of aspirin clearly outweigh the risks, it is important to take into consideration the overall cardiovascular risk profile of each individual patient.

Steve Chaplin

Reference

- Critical Leg Ischaemia Prevention Study (CLIPS) Group. Prevention of serious vascular events by aspirin amongst patients with peripheral arterial disease: randomized, double-blind trial. J Intern Med 2007;261:276–84.

What is aspirin resistance?

March 2010Br J Cardiol 2009;17(Suppl 1):S5-S7 Leave a comment

Variable and sometimes ineffective drug treatment is not uncommon in the treatment of cardiovascular disease.(1) In most cases lack of patient compliance is the explanation but other reasons may also exist. In the case of aspirin, “low responsiveness” or “resistance” to aspirin in pharmacological terms would mean that the compound fails to reach its therapeutic goal, i.e. inhibition of platelet COX-1-dependent thromboxane formation. However, in vivo there might be also changes in platelet sensitivity or “residual” platelet activity independent of aspirin treatment, probably unrelated to the drug’s pharmacodynamic actions.(2)