Medical therapy in the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension

Physicians are advised to consult the latest SPC (summary of product characteristics) for all medications

Calcium channel blockers

At the time of the diagnostic cardiac catheterisation, vasoreactivity testing is carried out to identify those patients who might benefit from long-term calcium channel blockers (CCBs). Less than 10% of patients with IPAH are positive acute responders (ESC 2009 guidelines), and only about half of these patients demonstrate long-term improvement with CCBs.8

The usefulness of vasoreactivity testing (see the chapter on Investigation of PH) is less clear in other subclasses of pulmonary arterial hypertension. CCBs must not be given to patients who have not undergone vasoreactivity testing or to those with a negative test response. In these patients, the deleterious effect on myocardial function in the absence of reduced pulmonary vascular resistance may cause clinical deterioration or death. The prognosis of long-term responders who are optimally managed with CCBs is very good.

The most commonly used CCBs are nifedipine, diltiazem and amlodipine.8,9,10 The choice is based on the patient’s heart rate, nifedipine and amlodipine being used for those with a relatively slow heart rate and diltiazem in those with a faster heart rate. The drugs are started at low doses and titrated up to the maximum tolerated dose (systemic hypotension and peripheral oedema are the usual limiting factors). Efficacy has been shown for this group of agents at high doses—120-240mg nifedipine per day, 240-720mg diltiazem per day and up to 20mg per day for amlodipine.

These patients require particularly close follow-up and are normally recatheterised after achieving a maximum tolerated dose of the CCB. If the patient does not improve to WHO-FC I or II and have normal or near normal haemodynamics, then he or she is classed as a non-responder and additional disease-targeted therapy is commenced according to the algorithm. Pulmonary hypertension can break through CCB treatment at any time during follow-up; and care must be taken to ensure that these patients are continuing to respond to CCBs.

Learning point

- Calcium channel blockers may have a role in “vasoreactor positive” patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension

Prostanoids

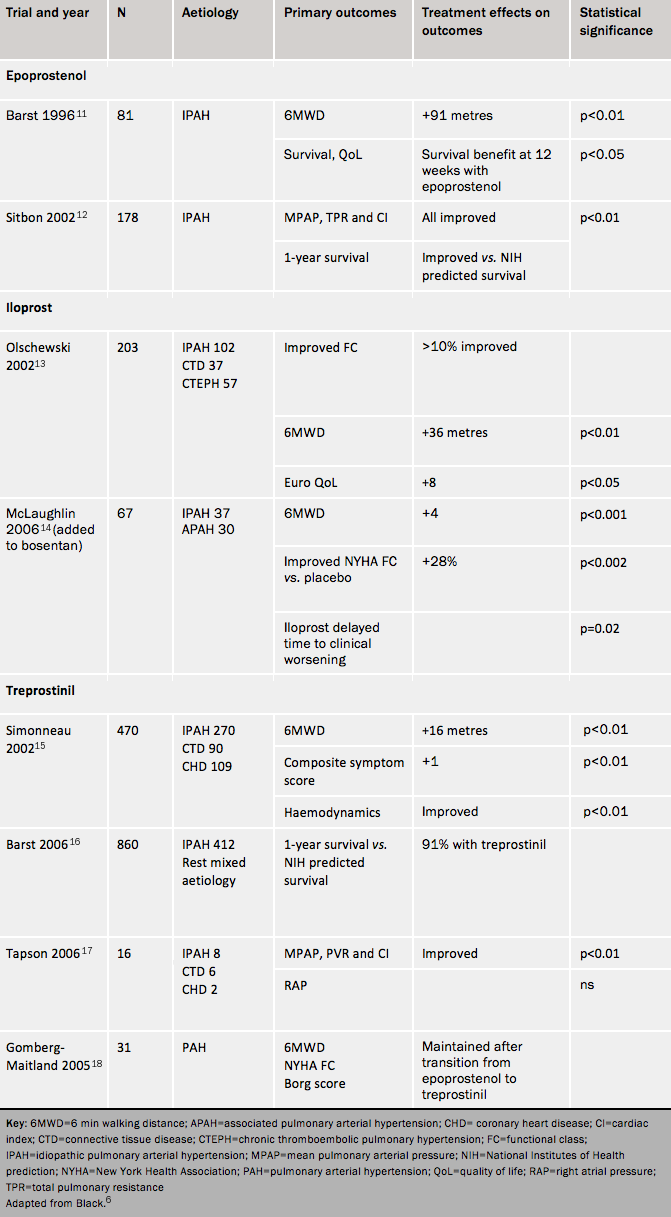

Prostanoids are analogues of prostacyclin. This compound, produced by endothelial cells, is a potent vasodilator and inhibitor of platelet aggregation, with cytoprotective and antiproliferative effects. Patients with PAH have reduced expression of prostacyclin synthase in the pulmonary arteries. The four prostanoids in current clinical use are epoprostenol, iloprost, treprostinil and beraprost. In most patients the dose requires progressive uptitration over time. A brief outline of the agents in this class, and the trial and observational evidence for each, is shown in table 1. Almost all trials in pulmonary hypertension have been carried out to obtain licensing.

The general side effects for the prostanoids are headache, flushing, jaw pain, diarrhoea, nausea and myalgia. Side effects often worsen with dose increases but then rapidly subside. The tables summarise trial results for each class of agent and these are not discussed in the paragraphs below.

Epoprostenol

Epoprostenol is the gold standard therapy for patients in WHO FC IV. It has an important role in patients who are deteriorating rapidly in FC III. Intravenous epoprostenol improves symptoms, functional class, exercise capacity and haemodynamics in IPAH, and is the only treatment shown to improve survival in a randomized study11 although this was not a pre-specified end point. Observational studies have also confirmed long-term benefits of epoprostenol in IPAH. For instance, Sitbon12 reported improved survival in comparison to historical controls, with survival rates of 85%, 70%, 63% and 55%, respectively, at one, two, three and five years.

Epoprostenol is delivered by continuous intravenous infusion through a permanent indwelling catheter (since it has a half-life of 1-2 minutes and is only stable at room temperature for a few hours). The starting dose is commonly 1-2ng/kg/min; this dose is up-titrated during the first few days of treatment according to symptoms, side effects and efficacy. Further dose increases during long-term follow-up can be made according to the patient’s response to treatment, and there is no upper dose limit. Most adults are typically treated in the range of 20-40ng/kg/min.

The patient and their carer are trained and must be competent to manage the delivery system before discharge from hospital. There is a risk of delivery system malfunction, and patients should know how to troubleshoot this. Patients should be provided with a spare pump in case of malfunction. Infection and sepsis may be life-threatening. Abrupt interruption of the infusion may lead to a potentially fatal rebound pulmonary hypertension. Clearly, this drug needs to be initiated and monitored by those with special expertise in the treatment of pulmonary hypertension.

Iloprost

Iloprost is delivered by aerosol, which is administered by a nebuliser three-hourly during the day. The patient goes without treatment while they are asleep.

Compared with inhaled placebo, inhaled iloprost increases exercise capacity and improves symptoms and clinical events. Some physicians use iloprost as an intravenous agent.

Treprostinil

Treprostinil may be administered through the subcutaneous or intravenous route or by aerosol.

Treprostinil is usually given subcutaneously with a microinfusion pump and subcutaneous catheter. It improves exercise capacity, symptoms and haemodynamics. Subcutaneous infusion overcomes some of the difficulties and complications of intravenous infusion. It frequently causes important infusion site pain by activation of prostacyclin pain receptors. Patients need assistance in managing infusion site pain from a healthcare professional experienced in using treprostinil. If the pain becomes intolerable then it is appropriate to consider an intravenous infusion.

Treprostinil has a half-life of about two hours and its infusion pump needs less frequent changes of the drug than epoprostenol.

Intravenous treprostinil has been approved in the US for PAH patients who cannot tolerate subcutaneous infusion. The effects appear comparable to those of epoprostenol but at a higher dose. In one open-label study Tapson17 reported improvements in 6MWT with intravenous treprostinil monotherapy. In another, Gomberg-Maitland18 reported similar exercise endurance among patients taking IV epoprostenol and IV treprostinil. The latter is more convenient for the patient because the reservoir needs to be changed only every 48 hours (compared to every 12 hours with epoprostenol).

Preliminary data from the TRIUMPH (inhaled TReprostinil sodium in Patients with severe Pulmonary arterial Hypertension) study suggest improved exercise capacity in patients taking inhaled treprostinil on a background of bosentan or sildenafil.19 Aerosolised treprostinil has been assessed in combination and appears to be beneficial.

Beraprost

Beraprost is not currently available in Europe. It is administered orally. Two randomised controlled trials have shown only short-term improvement in exercise capacity without haemodynamic benefit.20,21

Learning points

- Prostanoids are potent vasodilator analogues of prostacyclin

- Most agents are delivered by infusion. Although they may improve symptoms of PH, they are challenging to use