Earlier reports suggest differences in presentation between South Asians and white Europeans experiencing acute coronary syndromes. To compare the demographics and presentation of British South Asians, a long-term prospective survey of a consecutive series of British South Asians was conducted. South Asian patients were analysed as six distinct subgroups, with an overall comparison to a white European cohort.

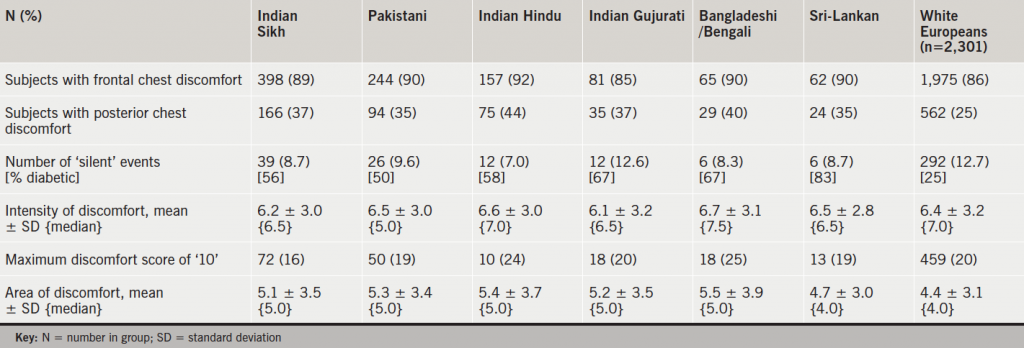

South Asian patients were of similar mean age, and male predominance (66%), across all subgroups, but as a whole, were younger (62 ± 13 years) than white Europeans (69 ± 14 years), p<0.001. Diabetes was markedly more prevalent in South Asians (range 42–55%) compared with white Europeans (17%), p<0.001. South Asians, as a whole, reported a larger average area of discomfort (5.2 ± 3.5) than did white Europeans (4.4 ± 3.1), p<0.001. Posterior chest discomfort was reported by 38% of all South Asians (range 35–44%) and by 25% of white Europeans, p<0.001. The average intensity of discomfort was similar between white Europeans (6.4 ± 3.2) and South Asian cohorts (6.4 ± 3.0), p=0.80. Differences in ‘intensity of discomfort’ between South Asian subgroups did not reach significance. Silent cardiac events were more common in white Europeans (12.7%) than in South Asians (9.0%), p<0.001.

In conclusion, Asian patients were younger, more likely to be diabetic and tended to report discomfort over a greater area of their body, than did white Europeans. No differences were found between individual South Asian subgroups for pain distribution (extent), character or intensity. South Asian women tended to report a wider distribution of discomfort and intensity than did men across all subgroups.

Introduction

Approximately 4.2 million people (7.5% of population), whose racial origins are from South Asia, live in the UK. High rates of coronary disease in Asians,1-4 seem likely to be influenced by genetic factors.5 We have previously reported differences in the presentation of coronary syndromes between British South Asians, as a whole, and white Europeans.6

Approximately 4.2 million people (7.5% of population), whose racial origins are from South Asia, live in the UK. High rates of coronary disease in Asians,1-4 seem likely to be influenced by genetic factors.5 We have previously reported differences in the presentation of coronary syndromes between British South Asians, as a whole, and white Europeans.6

The term ‘South Asian’ describes around 1.5 billion people (22.5% of the world’s population), occupying regions as diverse as Sri Lanka to Nepal. A wide variety of genotypes, cultures, diets, belief systems, educational attainment, socioeconomic status and risk factors are encompassed.7,8

Some reports suggest that atypical presentations in patients suffering myocardial infarction have led to an increased risk of delays in South Asians seeking medical attention,9,10 particularly in women,11 resulting in less aggressive clinical management,12 and worse in-hospital mortality.13 More recently, two large studies have reported similar,4 or greater intervention rates,14 across all South Asian subgroups. We performed a 10-year prospective survey of several South Asian subgroups, presenting with acute coronary syndromes, to determine any differences in symptomology.

Subjects and methods

Patients

Consecutive South Asian patients, requiring hospital admission for an acute coronary syndrome, were recruited between November 2001 and June 2012. Patients self-defined themselves to country, region and/or cultural-religious belief systems, which established six main subgroups (table 1). Inevitable and unavoidable overlaps of religion, geography and culture are encompassed. By asking patients to self-classify themselves we determined they would distinguish a self-defined grouping and identity. Major characteristics of symptom presentation were compared with a cohort of 2,301 white European patients, consecutively recruited between 2001 and 2006.6

Ethical approval was obtained through the National Research Ethics Service (reference 06/q0407/43) and all subjects gave written consent.

Study design

Patients completed a four-question survey, comprising:

- Location of symptoms on a pre-drawn schematic

- Choice of descriptive symptom terms

- Estimation of intensity of symptoms (1 = minor discomfort to 10 = worst pain)

- Patients were asked to define their perceived ‘origins’.

Subjects were given language assistance if required.

Data analysis

All analyses examined the overall differences in outcomes between the six South Asian subgroups. The majority of outcomes were measured on a categorical scale; compared between groups using the Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test. Two outcomes were measured on a continuous scale, using analysis of variance. Analysis was performed using STATA® software (version 12.1).

Results

Of 1,329 patients surveyed, 203 (15.3%), comprising 48 ‘Punjabi’ (24%), 38 ‘Indian’ (19%), 33 North Indian (16%), 22 South Indian (11%), 16 Mauritian (18%), 13 Christian Indians (6%) and 33 others (16%), were excluded. Exclusion was based on ‘too broad a descriptive term’ or ‘too small a group to analyse’.

Demographics for the six subgroups (n=1,126) are shown in table 1. Overall, the South Asian cohort comprised a total of 747 men (66.3%) and 379 women.

South Asians were of similar mean age, with a male majority (60–63%) over all subgroups. The white European cohort (n=2,301) had a similar male preponderance (62%), but was, on average, older at presentation (69 ± 14 years) than any South Asian subgroup (p<0.001). The prevalence of diabetes in white Europeans (17%) was less than half that of any South Asian subgroup (range 42–55%).

Acute coronary events

Overall, there was a significant difference in the type of acute coronary syndrome between the two broad ethnic groups. Compared with white Europeans, South Asians had a higher proportion of ST-elevation events (38% vs. 21%, p<0.001) and a lower proportion of non-ST-elevation events (29% vs. 40%, p<0.001).

Location and extent of discomfort

Statistically, the proportion of white Europeans (table 2) experiencing anterior chest discomfort (1,975 of 2,301 – 86%) was marginally lower than in South Asians (1,007 of 1,126 – 89%), p=0.009, largely due to the large sample size. Posterior chest discomfort was reported by more than a third of all South Asians (423 of 1,126 – 38%, range 35–44%) and a smaller proportion of white Europeans (562 of 2,301 – 25%), p<0.001. Posterior chest discomfort was more widely reported by women than men for every South Asian subgroup and by white Europeans.

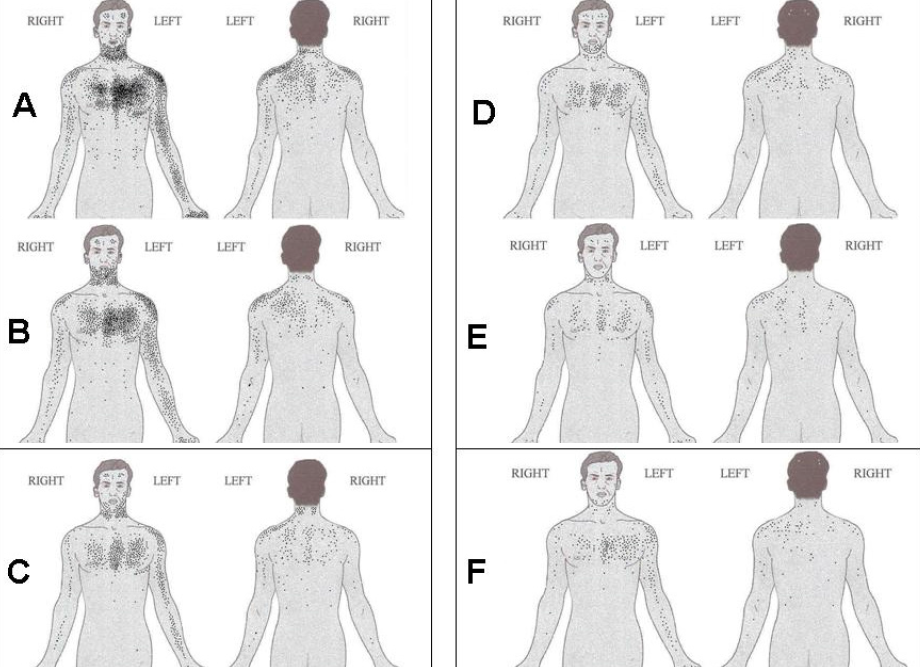

South Asians, as a whole, reported a larger area of discomfort (5.2 ± 3.5) than did white Europeans (4.4 ± 3.1), p<0.001 (table 2). Every South Asian subgroup (figure 1A) reported a mean area of discomfort larger than did the white European cohort (figure 1B). In South Asians (figure 2), the most common extra-thoracic locations for discomfort included arms (37%), neck (16%) and jaw (8%) (figure 3). In white Europeans, the distribution was similar with values of 40% for arms, 14% for neck and 7% for jaw.

Overall, silent cardiac events were more common in white Europeans (12.7%) than in South Asians (9.0%), p<0.001, despite a significantly higher proportion of South Asians being diabetic (58%) compared with the white Europeans (25%), p<0.001. More than 50% of individual South Asians experiencing silent events were diabetic.

The average intensity of discomfort (mean ± standard deviation [SD]) was similar between white Europeans (6.4 ± 3.2) and South Asian cohorts (6.4 ± 3.0), p=0.80. Any differences for ‘intensity of discomfort’ observed between individual South Asian subgroups did not reach significance. A higher proportion of white Europeans (19.9%) than South Asians (18.8%) reported ‘maximum discomfort’, p=0.02. For South Asians, ‘weight’ was the most commonly used term for discomfort (29–47% of patients), followed by ‘squeeze’ (19–35%), ‘ache’ (14–25%), ‘burn’ (6–17%), ‘stabbing’ (4–13%) and ‘shooting’ (0–4%). White Europeans followed a similar trend although ‘ache’ was a more frequent choice than ‘squeeze’.

Discussion

Earlier work suggests South Asians report a greater frequency,15 intensity and area of discomfort than do white Europeans.6 Variations in risk factors,16-18 and an excess prevalence of coronary disease are previously described for South Asians.1,19 Most studies ‘position’ Bangladeshis, Pakistanis and Muslim Indians at a cardiovascular disadvantage to other South Asians,2,4 possibly with Bangladeshis having the worst risk profile.20 We postulated there might be variations in presentation within a population broadly encompassed as ‘South Asian’.

As in earlier studies, we found South Asians to be younger than white Europeans and with an overall prevalence of diabetes,16,21 reaching 2.7 times greater than in white Europeans. High levels of diabetes are described in British Pakistanis (22.4%) and Bangladeshis (26.6%),19 although our cardiac selected patients far surpass these values (range 42–55%).

We found that discomfort over the back of the chest was reported more frequently by each of the South Asian subgroups as compared with white Europeans. Discomfort limited exclusively to the back was unusual and similarly infrequent in South Asians (0.3%) and white Europeans (0.7%); a feature noteworthy with ‘differentials’ including aortic dissection.

Generally, South Asians had a wider distribution of discomfort, with an excess of neck and jaw discomfort compared with white Europeans. Atypical presentations have been reported to be more common in Indo-Asians experiencing myocardial infarction, than in Europeans.22-24 Differences in location of chest discomfort, between Indians, Bangladeshis and Pakistanis with angina, were highlighted by the Newcastle Heart project; the anatomical location being generally more variable than in Europeans.25 Across all six of our South Asian subgroups, discomfort beyond a chest distribution was most common in the arms, followed by neck and the jaw. In the majority of these subgroups it was women who described more arm, neck and jaw pain. South Asian women, in our study, appear similar to women of other races in tending to a wider distribution of cardiac pain with more back,26,27 arm, hand,28 throat, neck and jaw pain than do men.24,26,29

The proportion of patients in our study with ‘silent’ episodes was modest compared with earlier studies,13 where patients presenting with myocardial infarction or ischaemia, without chest pain, have previously been described as having a poor prognosis.13,30

In common with earlier studies, women in our study showed a trend to report higher levels of pain discomfort and assigned larger areas of discomfort than did men.28,31,32 Failure to recognise an atypical presentation, female sex and ‘non-white’ race, are features suspected to account for failure to hospitalise patients with acute coronary syndromes and worse outcome.33

We have also demonstrated language issues across all South Asian groups, but to a lower extent than some reports, possibly related to the specific ethnic mix and relative prosperity of this London borough. Language problems were almost five times more prevalent for women than for men. An inability to communicate a symptom may lead to an exaggeration of symptoms, making the diagnosis in women even more difficult. South Asians in the UK have been described as having a tendency to ‘globalise’ symptoms, compared with the white population,34 and are more likely to seek immediate care.35 Some authors also report that descriptions of chest pain in Asian women are ‘less reliable’ than in men.25,36

Limitations to the study

The study is limited by survivor bias. Language, and its nuances, may have influenced the choice of terms, although minimised by our use of images (figure 1). Furthermore, we accept that an ‘overlap’ of territories and religious affiliations has occurred. Some authors suggest ‘religious stratification’ might better determine coronary disease risk,37,38 but a perception and sensitivity to ‘Islamophobia’ prevented using this as a practical denominator in our study. This was not a genetic-based study. Individuals calling themselves ‘Pakistani’, as opposed to ‘Indian’, base this on their country of origin (formed as recently as 1947), a partition that is artificial and predominantly based on religious affiliation. Even more recently (1971), two countries on the Indian subcontinent were further split (creating the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and the Peoples Republic of Bangladesh). Our subgroups, including subjects identifying with the Gujurat State or Sikhism, have been in existence considerably longer (millennia and 500+ years, respectively). We suggest an association with a region State (Gujurat for example), with a distinct language, food, customs and ‘inter-marriage’ must surely be influential on behaviour, and potentially clinical presentation. We totally accept there is an overlap between any groupings and would argue this might also include commonly ascribed simple definition by nationality, which in one case has been in existence for only 43 years.

Conclusion

Our observations reveal that South Asian patients are younger, more likely to be diabetic and tend to report a higher intensity of pain and over a greater area of their body, including over their backs, than do white Europeans. Differences between individual subgroups of South Asians were less obvious and possibly confounded by some overlap between these different groups. This study represents one of few studies,37,39 attempting to examine subgroup heterogeneity among South Asians in the UK.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Authorship statement

All authors have contributed to the writing and interpretation of these study data.

Key messages

- All South Asian subgroups reported a greater distribution of pain, but of similar intensity to white Europeans

- The location of chest discomfort and intensity was similar between South Asian subgroups

- South Asian women reported a wider distribution of discomfort and intensity than did men across all subgroups

References

1. Bhopal R. What is the risk of coronary heart disease in South Asians? A review of UK research. J Pub Health Med 2000;22:375–85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/22.3.375

2. Wild SH, Fischbacher C, Brock A et al. Mortality from all causes and circulatory disease by country of birth in England and Wales 2001–2003. J Public Health (Oxf) 2007;29:191–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdm010

3. Harding S, Rosato M, Teyhan A. Trends for coronary heart disease and stroke mortality among migrants in England and Wales, 1979–2003: slow declines notable for some groups. Heart 2008;94:463–70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2007.122044

4. Bansal N, Fischbacher CM, Bhopal RS et al. Myocardial infarction incidence and survival by ethnic group: Scottish health and ethnicity linkage retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003415. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003415

5. Whincup PH, Gilg JA, Papacosta O et al. Early evidence of ethnic differences in cardiovascular risk: cross sectional comparison of British South Asian and white children. BMJ 2002;324:1–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7338.635

6. Teoh M, Lalondrelle S, Roughton M, Grocott-Mason R, Dubrey SW. Acute coronary syndromes and their presentation in Asians and Caucasian patients in Britain. Heart 2007;93:183–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2006.091900

7. Bhopal R, Hayes L, White M et al. Ethnic and socio-economic inequalities in coronary heart disease, diabetes and risk factors in Europeans and South Asians. J Public Health Med 2002;24:95–105. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/24.2.95

8. Zaman MJS, Patel KCR. South Asians and coronary heart disease: always bad news? Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:9–11. http://dx.doi.org/10.3399/bjgp11X548901

9. Shaukat N, de Bono DP, Cruickshank JK. Clinical features, risk factors and referral delay in British patients of Indian and European origin with angina matched for age and extent of coronary atheroma. BMJ 1993;307:717–18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.307.6906.717

10. Sekhri N, Timmis A, Hemingway H et al. Is access to specialist assessment of chest pain equitable by age, gender, ethnicity and socioeconomic status? An enhanced ecological analysis. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001025. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001025

11. Kendall H, Marley A, Patel JV et al. Hospital delay in South Asian patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction in the UK. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2012;20:737–42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/2047487312447844

12. Feder G, Crook AM, Magee P, Banerjee S, Timmis AD, Hemingway H. Ethnic differences in invasive management of coronary disease: prospective cohort study of patients undergoing angiography. BMJ 2002;324:511–16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7336.511

13. Canto JG, Shlipak MG, Rogers WJ et al. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and mortality among patients with myocardial infarction presenting without chest pain. JAMA 2000;283:3223–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.283.24.3223

14. Zaman MJS, Philipson P, Chen R et al. South Asians and coronary disease: is there discordance between effects on incidence and prognosis. Heart 2013;99:729–36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302925

15. Zaman MJS, Shipley MJ, Stafford M et al. Incidence and prognosis of angina pectoris in South Asians and Whites: 18 years of follow-up over seven phases in the Whitehall-II prospective cohort study. J Pub Health 2010;33:430–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdq093

16. McKeigue PM, Shah B, Marmot MG. Relation of central obesity and insulin resistance with high diabetes prevalence and cardiovascular risk in South Asians. Lancet 1991;337:382–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0140-6736(91)91164-P

17. Chambers JC, Eda S, Bassett P et al. C-Reactive protein, insulin resistance, central obesity, and coronary heart disease risk in Indian Asians from the United Kingdom compared with European whites. Circulation 2001;104:145–50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.104.2.145

18. Williams ED, Stamatakis E, Chandola T, Hamer M. Physical activity behaviour and coronary heart disease mortality among South Asian people in the UK: an observational longitudinal study. Heart 2011:97:655–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2010.201012

19. Bhopal R, Fischbacher C, Vartiainen E, Unwin N, White M, Alberti G. Predicted and observed cardiovascular disease in South Asians: application of FINRISK, Framingham and SCORE models to Newcastle Heart Project data. J Public Health 2005;27:93–100. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdh202

20. Bhopal R, Unwin N, White M et al. Heterogeneity of coronary heart disease risk factors in Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, and European origin populations: cross sectional study. BMJ 1999;319:215–20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.319.7204.215

21. Tillin T, Forouhi NG, McKeigue PM, Chaturvedi N; for the SABRE Study Group. Southall and Brent REvisited: cohort profile of SABRE, a UK population-based comparison of cardiovascular disease and diabetes in people of European, Indian Asian and African Caribbean origins. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41:33–42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyq175

22. Lear JT, Lawrence IG, Pohl JEF, Burden AC. Myocardial infarction and thrombolysis: a comparison of the Indian and European populations on a coronary care unit. J R Coll Phys 1994;28:143–7.

23. Barakat K, Wells Z, Ramdhany S, Mills PG, Timmis AD. Bangladeshi patients present with non-classic features of acute myocardial infarction and are treated less aggressively in east London. Heart 2003;89:276–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/heart.89.3.276

24. Zaman MJ, Junghans C, Sekhri N et al. Presentation of stable angina pectoris among women and South Asian people. CMAJ 2008;179:659–67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.071763

25. Fischbacher CM, Bhopal R, Unwin N, White M, Alberti KGMM. The performance of the Rose angina questionnaire in South Asian and European populations: a comparative study in Newcastle, UK. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30:1009–16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ije/30.5.1009

26. Goldberg R, Goff D, Cooper L et al. Age and sex differences in presentation of symptoms among patients with acute coronary disease: the REACT trial. Cor Art Dis 2000;11:399–407. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00019501-200007000-00004

27. Kyker KA, Limacher MC. Gender differences in the presentation and symptoms of coronary artery disease. Curr Womens Health Rep 2002;2:115–19.

28. Ghezeljeh TN, Momtahen M, Tessma MK, Nivramesh MY, Ekman I, Emami A. Gender specific variations in the description, intensity and location of angina pectoris: a cross sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud 2010;47:965–74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.12.021

29. Philpott S, Boynton PM, Feder G, Hemingway H. Gender differences in descriptions of angina symptoms and health problems immediately prior to angiography: the ACRE study. Appropriateness of Coronary Revascularisation study. Soc Sci Med 2001;52:1565–75. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00269-0

30. Dorsch MF, Lawrance RA, Sapsford RJ et al.; for the EMMACE Study Group. Poor prognosis of patients with symptomatic myocardial infarction but without chest pain. Heart 2001;86:494–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/heart.86.5.494

31. Devon HA, Zerwic JJ. Symptoms of acute coronary syndromes: are there gender differences? A review of the literature. Heart Lung 2002;31:234–45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/mhl.2002.126105

32. Edwards M, Chang AM, Matsuura AC, Green M, Robey JM, Hollander JF. Relationship between pain severity and outcomes in patients presenting with potential acute coronary syndromes. Ann Emerg Med 2011;58:501–50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.05.036

33. Pope JH, Aufderheide TP, Ruthazer R et al. Missed diagnosis of acute cardiac ischaemia in the emergency department. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1163–70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200004203421603

34. Allison TR, Symmons DPM, Brammah T et al. Musculoskeletal pain is more generalised among people from ethnic minorities than among white in Greater Manchester. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:151–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ard.61.2.151

35. Chaturvedi N, Rai H, Ben-Shlomo Y. Lay diagnosis and health-care-seeking behaviour for chest pain in south Asians and Europeans. Lancet 1997;350:1578–83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(97)06243-0

36. Patel DJ, Winterbotham M, Sutherland SE, Britt RG, Keil JE, Sutton GC. Comparison of methods to assess coronary heart disease prevalence in South Asians. Nat Med J India 1997;10:210–13.

37. Williams ED, Nazroo JY, Kooner JS, Steptoe A. Subgroup differences in psychosocial factors relating to coronary heart disease in the UK South Asian population. J Psychosom Res 2010;69:379–87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.03.015

38. Williams ED, Stamatakis E, Chandola T, Hamer M. Physical activity behaviour and coronary heart disease mortality among South Asian people in the UK: an observational longitudinal study. Heart 2011;97:655–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2010.201012

39. Nazroo JY. South Asian people and heart disease: an assessment of the importance of socioeconomic position. Ethn Dis 2001;11:401–11.