Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust offers a primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) service accessed via a coronary care unit (CCU) nurse-based pre-alert system. We reviewed our pre-alert calls for 2013 to determine their appropriateness and assess whether patients were being correctly accepted/declined for PPCI by comparison with final discharge diagnosis.

There were 1,343 calls received, only 52% had chest pain and electrocardiogram (ECG) changes meeting criteria. There were 508 patients with a discharge diagnosis of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), 89% of whom were accepted directly.

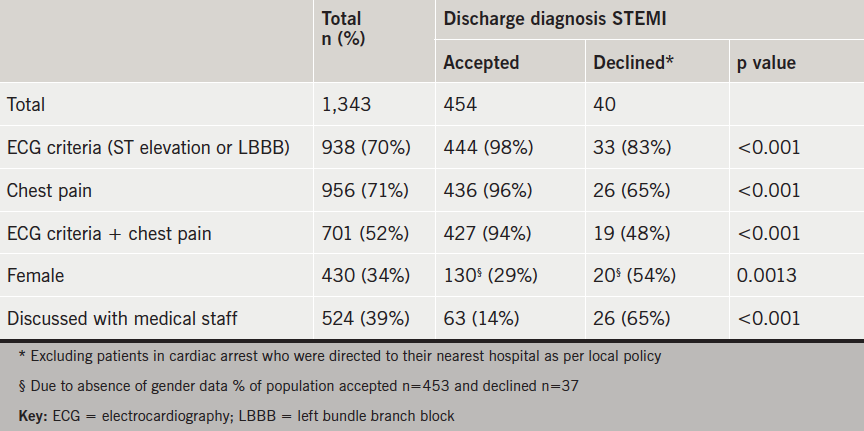

There were 54 cases with a final diagnosis of STEMI initially declined: 14 in cardiac arrest were directed to the emergency department (ED) as per policy; 18 had documented clinical reasons for declining; seven did not meet the criteria. There were 15 patients (3%) with chest pain and ECG criteria declined without a documented reason; three were subsequently accepted after assessment at their local hospital. Patients >80 years, female and with atypical presentation were more likely to be declined.

Of accepted patients, 132 (23%) had a diagnosis other than STEMI at discharge, 65% with an alternative cardiac diagnosis.

In conclusion, patients are frequently referred who do not meet symptom or ECG criteria. Most STEMI patients are appropriately accepted via our pre-alert pathway. Review of pre-alert services is essential to ensure timely and appropriate PPCI.

Introduction

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) is the preferred management for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI),1 and guidance committees have universally adopted this strategy as the ‘gold standard’ of care.2-4 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines mandate that PPCI is not only accessible to the entire population of the UK, but also that this is delivered in a timely fashion.4 Therefore, the early identification of appropriate STEMI patients for PPCI is essential, but this can be complicated due to the volume of patients, inadequate training and experience of frontline emergency care staff, and the implications of incorrect diagnoses. Consequently, PPCI centres have introduced local, structured, pre-alert systems to streamline assessment and service provision.

Hull and East Yorkshire (HEY) NHS Trust has provided a 24/7 reperfusion service to a population of 1.2 million since 2009, with the Emergency Department (ED) and PPCI centre on separate sites. The PPCI pathway is accessed by a centralised pre-alert telephone system managed by an experienced coronary care nurse team. The aim of this study was to review the PPCI pre-alert calls and patient discharge diagnoses for the calendar year 2013 to assess the appropriateness of calls and ensure that referrals were being correctly accepted/declined.

Materials and methods

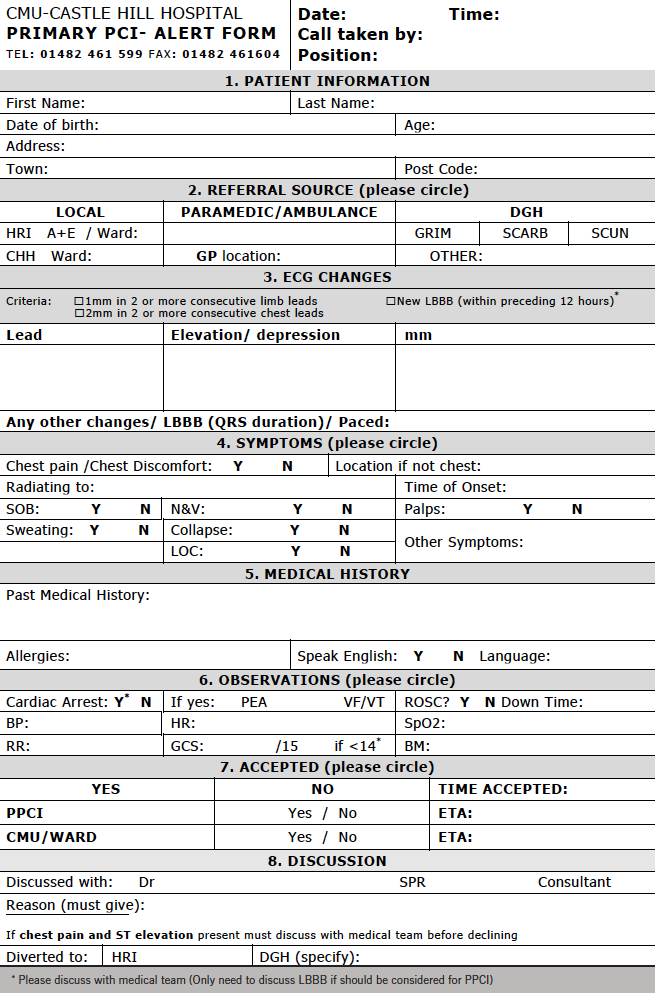

Pre-alert calls are received on a dedicated pre-alert telephone and triaged by senior nursing staff on the coronary care unit (CCU). All calls are documented on a standardised locally agreed proforma, designed to rapidly capture relevant information and facilitate a timely decision based on clinical and electrocardiogram (ECG) criteria. Criteria for referral and acceptance include the presence of symptoms consistent with STEMI within the last 12 hours, combined with ST-elevation (≥1 mm in two or more contiguous limb leads, or ≥2 mm in two or more contiguous precordial leads) or presumed new left bundle branch block (LBBB) on the ECG. ECGs are not routinely transmitted to the triage nurse, and decisions are based on the ECG findings reported by the referring paramedic or clinician. In cases of uncertainty, the triage nurse will discuss the decision with the on-site cardiology registrar or interventional consultant on-call. Cases accepted into the PPCI pathway are brought directly to the cardiac catheterisation laboratory at the PPCI centre.

All pre-alert proformas from 2013 were retrospectively reviewed to determine demographic data, symptoms, ECG findings, and the pre-alert decision. The final diagnosis relating to the episode of care was ascertained from hospital case records at the PPCI centre and surrounding district hospitals. In cases where a discharge diagnosis could not be established, the appropriateness of the triage decision was independently adjudicated by two interventional cardiologists.

Statistical analysis was performed on StatView version 5.0. Continuous variables were expressed as a mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables were documented as numbers (percentages). Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-squared test, with two-sided p values of <0.05 considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

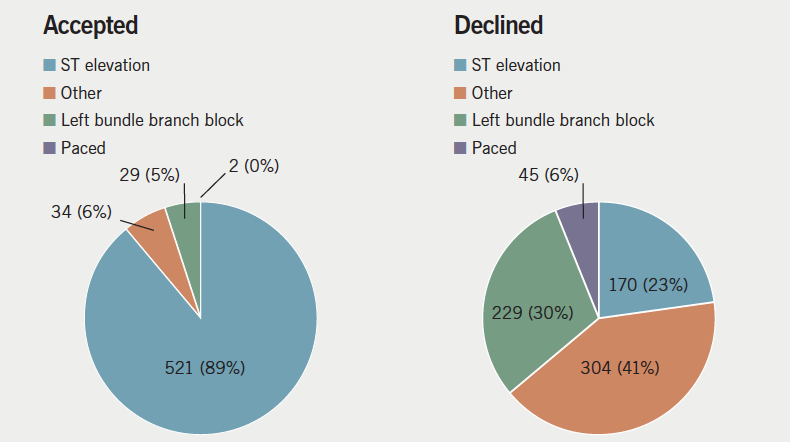

A total of 1,343 pre-alert referrals were made during 2013, of which 586 (44%) were accepted into the PPCI pathway. The mean age of referred patients was 68 ± 15 years and 853 (66%) were male. Most referred patients had chest pain (956, 71%), but only 701 (52%) had both chest pain and satisfied ECG criteria. A substantial proportion of referred patients (137, 10%) had neither chest pain nor satisfied ECG criteria for referral. Regarding those referred, 691 (51%) had ST elevation and 258 (19%) had LBBB. The ECG findings differed significantly between patients that were accepted and declined for PPCI (figure 1).

physician documented on proforma, in those accepted and declined

The final discharge diagnosis was STEMI for 508 (38%) patients (table 1). Of these, 454 (89%) were accepted directly from the initial pre-alert referral. There were 54 cases with a final diagnosis of STEMI initially declined: 14 in cardiac arrest were directed to their local emergency department (ED) as per regional policy; seven did not meet criteria for acceptance; 18 had clinical reasons for declining documented on the proforma, such as delayed presentation or significant comorbidities, for example end-stage metastatic disease. Fifteen patients (3% of STEMIs) satisfied clinical and ECG criteria but were declined without a documented explanation on the referral proforma; three of these patients were subsequently accepted following assessment at a local district hospital.

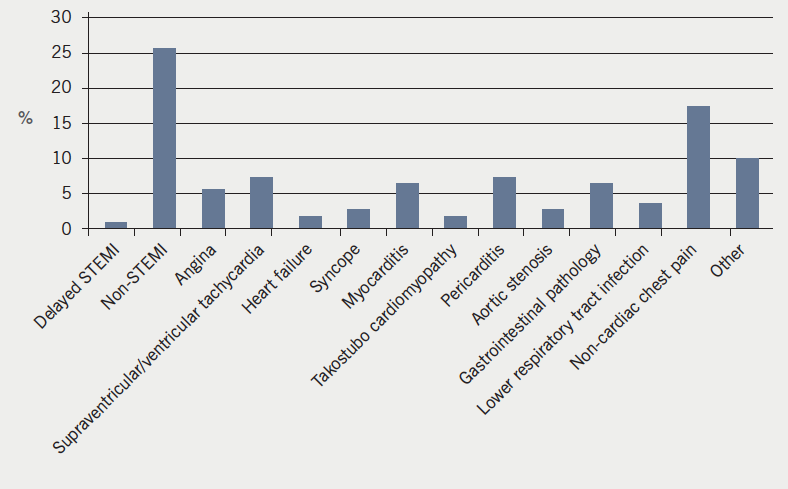

Of patients accepted into the PPCI pathway, 454 (77%) were discharged with a final diagnosis of STEMI, 86 (15%) had an alternative cardiac diagnosis, and 46 (8%) had a non-cardiac diagnosis. The alternative cardiac and non-cardiac diagnoses are shown in figure 2.

percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) pathway without final diagnosis of STelevation

myocardial infarction (STEMI)

Of the 258 pre-alert calls for LBBB, 29 (12%) were accepted into the PPCI pathway. Three referred LBBB patients had a final diagnosis of STEMI, all of whom were accepted. On review of these cases, one was incorrectly labelled LBBB at the time of referral (ECG actually showed anterior ST elevation), and the other two cases underwent PCI to significant coronary stenoses but on retrospective review did not have acute coronary artery occlusion at the time of coronary angiography despite the documented discharge diagnosis of STEMI.

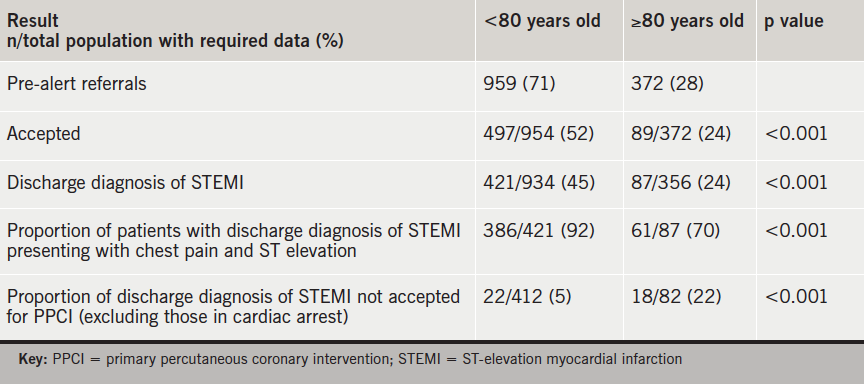

There were 372 (28%) patients referred aged ≥80 years, of which 119 (32%) had LBBB on ECG. Detailed results related to age comparison are described in table 2.

Of referrals, 430 (32%) were female. There were 167 (39%) accepted for PPCI, compared with 417 (49%) of males. Of females discharged with a diagnosis of STEMI, 127 (84%) were referred with chest pain and ST elevation on ECG, compared with 318 (91%) of males.

Of referrals, 1,217 (91%) came directly from paramedic crews. The remaining 126 (9%) were from local or regional hospitals, predominately ED. There were 60% (n=75) of referrals from the medical staff accepted compared with 42% (n=510) of paramedic referrals. Of patients referred by the medical team, 46% (n=57) were discharged with a diagnosis of STEMI versus 37% (n=451) of those referred from paramedics.

There were 52 (4%) documented calls with no identifiable patient information, which prevented recovery of final discharge diagnosis. Eight patients had no ECG or symptom data on which a judgement could be made. Of the remaining 44 patients; 42 had clear clinical or electrocardiographic reasons for declining. Two patients appeared to meet referral criteria but had no documented reason for declining. Therefore, maximally, 17 (3%) patients with a discharge diagnosis of STEMI were not accepted without documented reason.

Discussion

This study provides the first detailed analysis of PPCI pre-alert referrals in contemporary UK practice. A high proportion of calls to the pre-alert pathway do not fulfil referral criteria, but even without routine ECG transmission the pre-alert triage process effectively selects appropriate patients for PPCI, with 92% of accepted patients having a cardiological final diagnosis that would have been likely to require cardiology input, and only 3% of STEMI patients declined without a reason documented on the proforma. A number of these patients may have had a clinical reason for declining that was not documented on the pre-alert proforma, but this could not be ascertained in the present study. Comparative assessment of the overall performance is limited by the absence of published data from other centres or clear standards for benchmarking. Discussion with other UK PPCI centres suggests that access to the pathway via a dedicated nurse- or coordinator-led pre-alert phone line is widespread, but variation exists with regard to the availability of ECG transmission and routine blanket acceptance, the latter being, in practice, limited to same-site PPCI centre and EDs.

Other data suggest that paramedic interpretation of ECGs with ST elevation is robust (positive predictive value 82%).5 Therefore, the high referral level of patients not meeting criteria, particularly from the paramedic crews, may be the result of the paramedics’ perceived vulnerability in community assessment of patients with chest pain and desire for further expert support. Our aim is to maintain sound communication and supportive links with our referring paramedics, thus, maximising direct calls from the crews, as immediate ambulance transfer shortens door-to-balloon time,5 which is a key goal of the pathway. Providing an effective ECG transmission service would be the ideal long-term addition to optimise this support.

The findings that females and patients aged over 80 years with a discharge diagnosis are more likely to be declined for PPCI is likely attributed to atypical presentation and increased comorbidity, affecting appropriateness of acceptance for the PPCI pathway. Certainly, the atypical nature of the presentation is supported by the lower proportion of patients presenting with both chest pain and ST elevation on ECG in the population diagnosed with STEMI on discharge. The relationship between these demographics is apparent in published data6,7 and reflected in our study (53% of referred patients over 80 are female compared with 26% of those under 80). The importance of this is the poorer prognosis in both groups6,7 and evidence of delayed symptom to balloon time.7

Encouragingly, a high percentage (77%) of those accepted had a discharge diagnosis of STEMI, and, of the accepted not discharged with a diagnosis of STEMI, two thirds had a cardiological diagnosis. There is likely to be an acceptance bias towards those perceived to have a cardiological presentation, if not a STEMI, e.g. dysrhythmia with possible ST elevation or widespread ST elevation.

Amendments to our pathway have been supported in light of the results. We have questioned the role for acceptance of LBBB, which accounted for 19% of pre-alert calls, since in the present study no cases of acute thrombotic coronary occlusion were seen in these patients. Other UK data have reported a similar proportion of LBBB in patients accepted for PPCI of 5.5%, with only 17% of these having coronary occlusion in that series.8 At present, our approach is to continue to receive referrals for LBBB, but to only accept cases whose presentation is highly suggestive of acute myocardial infarction (MI), with mandatory discussion with the medical team prior to acceptance. We have mandated that no cases with chest pain and ST-elevation on the ECG can be declined without discussion with medical personnel, and that all declined cases must have a reason documented for declining the patient. This will help to improve our data, optimise patient care, and provide support to the pre-alert nursing team.

The results have additionally highlighted specific populations of patients that do not fulfil referral criteria, but should be considered unstable and high risk. This has led to a unified departmental decision for direct acceptance to the PPCI centre, particularly focusing on patients with transient ECG change and those now pain free but with persistent ECG changes.

Following this study, the pre-alert proforma has been redesigned to streamline data retrieval at the time of the pre-alert call and improve the completeness of data for further audit (appendix 1).

Limitations

This study only included activations of the PPCI pathway that occurred via the pre-alert call system. Other PPCI activation mechanisms, such as patients already on the cardiology wards or referrals made directly to medical staff would not have pre-alert proformas and would not be captured in this study. However, correlation with the PCI database for 2013 demonstrated that 93% of PPCI procedures performed were referred via the pre-alert system.

As our service currently has no facility for remote community ECG transmission, the ECG diagnosis was based on interpretation reported by on-scene staff rather than direct visualisation. Any inaccuracy in interpretation only reflects the information available at the time of the initial management decision.

There were some missing data, due to the nature of retrospective analysis of clinical data captured in a busy emergency setting. However, the amount of incomplete data was low, and unlikely to have substantially altered the analysis, as suggested by assessment of the absent data accounted for in the final results.

Since there are no data for comparison, or to act as a benchmark for our service, assessment of successful service provision must be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

Patients are frequently referred who do not meet symptom and ECG criteria, however, our pre-alert system correctly identifies the majority of appropriate STEMI patients without burdening the service with non-cardiological patients. Without comparable data, we cannot conclusively comment on our department’s performance, but hope minor alterations will enable improvement to an already acceptable service.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the Yorkshire Ambulance Service and East Midlands Ambulance Service for support in establishing our pre-alert system and continuing input. Many thanks to Dr Pierluigi Constanza, Dr Ali Ali, Dr Ali Razaand Dr Rachel Davidson for their assistance in data retrieval from our regional district general hospitals. Further thanks to Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital, Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, St George’s Hospital London, Southampton General Hospital, Royal Edinburgh Infirmary, Leeds General Infirmary, Nottingham City Hospital and Freeman Hospital Newcastle for liaising with us regarding their service structure.

Conflict of interest

None declared. No funding was received for this research.

Key messages

- Only 52% of pre-alert referrals had both chest pain and an electrocardiogram (ECG) meeting criteria

- 38% of all referrals had a discharge diagnosis of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)

- 77% of accepted patients had a discharge diagnosis of STEMI, with two thirds of the remainder having an alternative cardiac diagnosis

- 3% of patients meeting PPCI referral criteria were declined without a documented clinical reason

- Patients over 80 years and females with a discharge diagnosis of STEMI were less likely to present with ST elevation and chest pain and more likely to be declined

References

1. Grines CL, Brown KF, Marco J et al. A comparison of immediate angioplasty with thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. The Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction Study Group. N Engl J Med 1993;328:673–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199303113281001

2. Steg G, James SK, Badano LP, Borger MA, Ducrocq G, Gershlick AH. ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. The Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2569–619. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215

3. O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD et al. ACCF/AHA guideline 2013. ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2013;127:e362–e425. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742cf6

4. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE guidelines 167. The acute management of myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation. London: NICE, 2013. Available from: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/cg167

5. Le May MR, Dionne R, Maloney J, Poirier P. The role of paramedics in a primary PCI program for ST elevation myocardial infarction. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2010;53:183–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2010.08.003

6. Claussen PA, Abdelnoor M, Kvakkestad KM, Eritsland, Halvorsen S. Prevalence of risk factors at presentation and early mortality in patients aged 80 years or older with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2014;10:683–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/VHRM.S72764

7. Van der Meer MG, Nathoe HM, van der Graaf Y, Doevendans PA, Appelman Y. Worse outcomes in women with STEMI: a systematic review of prognostic studies. Eur J Clin Invest 2015;45:226–35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/eci.12399

8. Brown AJ, Hoole SP, McCormick LM, Malone-Lee M, Cacciottolo PJ, Schofield PM, West NE. Left bundle branch block with acute thrombotic occlusion is associated with increased myocardial jeopardy score and poor clinical outcomes in primary percutaneous coronary intervention activations. Heart 2013;99:774–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2012-303194