Replace or repair?

Heart valve repair is preferable to replacement for mitral prolapse where technically feasible, since it limits disruption to the tissues of the heart and avoids the implantation of artificial materials with all the attendant risks, including endocarditis and thrombosis (for mechanical valves).

Repair may also be feasible after infective endocarditis especially when sufficient delay has been clinically safe to allow healing of the tissues. A rheumatic mitral valve is difficult to repair and should usually be replaced except in parts of the world where anticoagulation is difficult to organise and an imperfect repair may be preferable to a biological replacement valve in the young. Whether to repair or replace for functional mitral regurgitation remains controversial5. The decision needs to be considered for each individual based on multiple factors including age, residual lV function, the grade of regurgitation and comorbidity.

Aortic valve repair may be feasible for non-stenotic bicuspid valves or aortic valve prolapse6. However aortic repair is highly specialised7 and not generally available. If aortic regurgitation is caused by dilatation of the aorta but with a structurally normal aortic valve it may be possible to replace or band the aorta to eliminate the regurgitation without the need for aortic valve surgery.

Types of replacement heart valve

Replacement valves are divided broadly into mechanical and biological valves8 (see table 19).

Mechanical valves

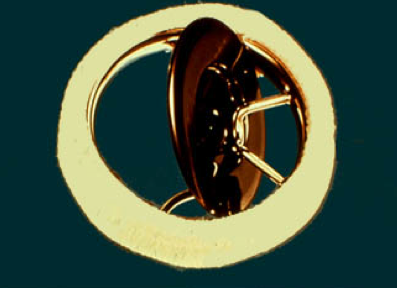

Ball and cage valves were first implanted in 1960 but were prone to causing obstruction and carry a high thromboembolic risk (see figure 4). Tilting disc valves were introduced in 1969 and are still in use (see figure 5). A more physiological design, the bi-leaflet mechanical valve was first introduced in 1977 and is now the most frequently implanted design of mechanical valve.

All mechanical valves consist of a housing containing the occluder and with a sewing ring attached outside (see figure 6). Much of the housing and the leaflets is composed of pyrolytic carbon. The leaflets may be made of pyrolytic carbon on a graphite base and the housing often contains strengthening with tungsten. The various Bi-leaflet designs differ in the composition and purity of the pyrolytic carbon, in the shape and opening angle of the leaflets, the design of the pivots, the size and shape of the housing and the design of the sewing ring. For example the St Jude Medical valve has a deep housing with pivots contained on flanges, the Carbomedics has a shorter housing allowing the leaflet tips to be imaged clearly on echocardiography and the On-X valve has a long, flared housing.

These valves can be mounted in the annulus, above the annulus or in an intermediate position.