Despite the significant improvements in both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in recent years, infective endocarditis (IE) remains a medical challenge due to poor prognosis and high mortality. Echocardiographically, the majority of the patients demonstrate vegetations on a single valve, while demonstration of involvement of two valves occurs much less frequently; triple-valve involvement is extremely rare. Reported operative mortality after triple-valve surgery is high and ranges between 20% and 25%.

Surgical treatment is used in approximately half of patients with IE because of severe complications. Reasons to consider early surgery in the active phase, i.e. while the patient is still receiving antibiotic treatment, are to avoid progressive heart failure and irreversible structural damage caused by severe infection, and to prevent systemic embolism. Prognosis in IE is influenced by four main factors: characteristics of the patient, the presence or absence of cardiac and non-cardiac complications, the infecting organism, and echocardiographic findings. Prognosis of right-sided native valve endocarditis is relatively good, with an in-hospital mortality rate of about 10%.

We present a case of a young man with triple-valve endocarditis followed by a brief review of the literature.

Introduction

Despite the significant improvements in both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in recent years, infective endocarditis (IE) remains a medical challenge due to poor prognosis and high mortality. IE varies according to the initial clinical manifestations, underlying cardiac disease, micro-organisms involved and the associated complications. Echocardiographically, the majority of patients demonstrate vegetations on a single valve, while demonstration of involvement of two valves occurs much less frequently; triple-valve involvement is extremely rare. In a series of 25 opiate addicts with echocardiographic evidence of valvular vegetations, no cases of triple-valve involvement were found.1 In a recent case-series of 77 patients with IE, the incidence of multi-valvular endocarditis (MVE) was 18%, with mitral and aortic valves most commonly affected.2

We present a case of a young, ex-intravenous drug user with triple-valve IE, who was managed successfully medically with a brief review of the published literature.

Case report

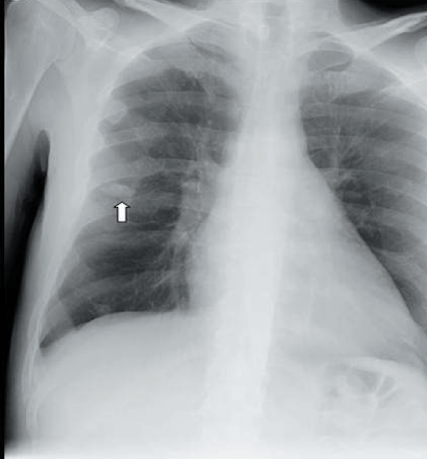

A 48-year-old man presented with non-specific symptoms of lethargy, anorexia and significant weight loss. He was an ex-intravenous drug user. The examination revealed a cachectic appearing male with a temperature of 37°C, a blood pressure of 83/57 mmHg and a pulse of 100 beats per minute. There were no clinical signs of IE or fresh ‘needle-track’ signs to note. His chest was clear to auscultation and his abdomen was soft and non-tender to palpation. Cardiovascular examination revealed a loud pan-systolic murmur along with an early diastolic murmur. Laboratory investigations showed a mild, normocytic anaemia, normal white cell and neutrophil count, but an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP). His non-specific presentation and laboratory results, together with examination findings, raised the suspicion of IE as a diagnosis, and three sets of blood cultures were drawn. Empirical antibiotics were started as per guideline recommendations. Chest X-ray also showed a small, well-demarcated mid-zone lesion, which was thought to be a septic lesion (figure 1). In view of the lesion on the chest X-ray, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the thorax was done that demonstrated a septic embolus (figure 2).

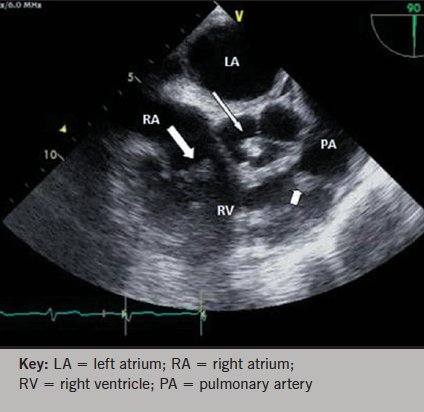

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) revealed an echogenic mass on the aortic valve. Subsequent transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) revealed moderate-to-severe aortic regurgitation and vegetations on the tricuspid, pulmonary and aortic valves (figures 3 and 4). The large prolapsing vegetation on the regurgitant aortic valve was also noted to be transiently in contact with the septal wall at the site where mural vegetation growth was seen (figure 5). There was also noted to be a patent foramen ovale with intermittent right-to-left shunting. All blood culture sets became positive for Streptococcus mutans after 48 hours and were shown to be fully sensitive to penicillin (minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC] 0.023 mg/L). His antibiotic regimen was, thus, altered to match sensitivities.

Streptococcus mutans is usually a left-sided organism. It can only be presumed that inoculation of the opposite side of the heart has occurred by means of the patent foramen ovale as he had intermittent right-to-left shunt, but the predominant shunt appeared to be from left to right.

His eventual antibiotic regimen was administered through a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line and consisted of treatment with gentamicin for two weeks, together with benzylpenicillin for six weeks, followed by vancomycin for one week, with return of both his CRP and temperature to normal. No plans for imminent surgical intervention were made on the wishes of the patient, and he was discharged home. His weekly repeated blood tests showed no evidence of infection for six weeks. He remained well and asymptomatic when reviewed in the clinic after three months.

Discussion

The major bulk of echocardiographically proven endocarditis occurs on a single valve. The involvement of two valves is much less common, and triple – or quadruple – valve involvement has very rarely been reported. Kim et al.2 described that multi-valve endocarditis represents a separate clinical entity, recognised to be an independent risk factor affecting survival. It was demonstrated that the mortality rate was higher in patients with infection of two or more valves than in patients with involvement of a single valve (21% vs. 18%, respectively). Furthermore, patients with involvement of multiple valves had an increased rate of complications, such as congestive cardiac failure (64%) and acute renal failure (50%) that often required early surgery.2

López et al.3 reported that in MVE, independent predictors of hospital mortality were heart failure and persistent infection. It was demonstrated that persistent infection increased the risk of in-hospital mortality four-fold. Persistent infection reflects that failure of antibiotic treatment to control the infectious process.4 Because of the dire prognosis, patients in this clinical situation should be treated surgically. López et al.3 found no difference in the demographic or microbiologic profile between MVE and single-valve endocarditis (SVE). Although MVE was more frequently associated with the appearance of heart failure than SVE, short-term mortality was similar in both groups, probably because of the more aggressive therapeutic management of MVE.

The current European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines5,6 recommend that surgical treatment should be performed in native valve IE, when the following indications are present:

- Development of heart failure, especially if moderate or severe

- Severe aortic or mitral regurgitation with evidence of abnormal haemodynamic status

- Endocarditis caused by fungi or other resistant organisms

- Peri-valvular infection with fistula or abscess formation

- Signs of uncontrolled infection such as persistent fever and positive blood cultures beyond 7 to 10 days of appropriate antibiotic therapy.

Other possible indications include:

- Embolic events, in spite of adequate antibiotic therapy, or associated with vegetations >10 mm in diameter

- Presence of vegetations >10 mm, with or without embolic events, if mobile and associated with other signs of severe illness.

The current guidelines5,6 recommend that surgical treatment should generally be avoided in patients with right-sided IE, although it has to be considered in the following situations:

- Right-sided IE secondary to severe tricuspid regurgitation with a poor response to diuretic therapy

- IE caused by organisms that are difficult to eradicate or bacteraemia for at least seven days, despite adequate antimicrobial therapy

- Tricuspid valve vegetations >20 mm that persist after recurrent pulmonary emboli, with or without concomitant right heart failure.

MVE is a poorly studied entity, and there is little information regarding its main characteristics, prognosis, and the best management approach. Despite the advancements in operative techniques in the recent years, triple-valve surgery remains challenging. The few published studies include small numbers of patients, and did not reflect the characteristics of the general population with endocarditis.2,7 The results of these studies are contradictory: some associate multiple-valve disease with a worse prognosis,7 whereas others found no such association.2 Optimal therapeutic management also remains unclear; some studies suggest surgery improves the prognosis in patients with MVE,7 although concrete evidence is lacking. Further research and recommendations are needed in order to manage these complex patients in the best possible way.

Acknowledgement

The authors appreciate the support of the Department of Echocardiography, Royal Glamorgan Hospital, for their help in providing the images of the patient.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Key messages

- Multi-valve endocarditis (MVE) is a poorly studied entity with little information regarding its main characteristics, prognosis and management

- MVE represents a separate clinical entity, recognised to be an independent risk factor affecting survival

- Despite the recent advancements in operative techniques, multiple-valve surgery remains challenging

- Further research is needed to explore and identify better management options in these patients.

References

1. Andy JJ, Sheikh MU, Ali N et al. Echocardiographic observations in opiate addicts with active infective endocarditis. Frequency of involvement of the various values and comparison of echocardiographic features of right- and left-sided cardiac valve endocarditis. Am J Cardiol 1977;40:17–23.

2. Kim N, Lazar JM, Cunha BA, Liao W, Minnaganti V. Multi-valvular endocarditis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2000;6:207–12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-0691.2000.00065.x

3. López J, Revilla A, Vilacosta I et al. Multiple-valve infective endocarditis: clinical, microbiologic, echocardiographic, and prognostic profile. Medicine (Baltimore) 2011;90:231–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MD.0b013e318225dcb0

4. Revilla A, López J, Vilacosta I et al. Clinical and prognostic profile of patients with infective endocarditis who need urgent surgery. Eur Heart J 2007;28:65–71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehl315

5. Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis. The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J 2015;36:3075–123. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319

6. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014;129:e521–e643. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000031

7. Mihaljevic T, Byrne JG, Cohn LH, Aranki SF. Long-term results of multivalve surgery for infective multivalve endocarditis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2001;20:842–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1010-7940(01)00865-X